Rilke, Rainer Maria Letters to a Young Poet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Death Motif in the Love Poems of Theodore Roethke

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1980 The Death Motif in the Love Poems of Theodore Roethke George Wendt Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wendt, George, "The Death Motif in the Love Poems of Theodore Roethke" (1980). Dissertations. 2106. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2106 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1980 George Wendt THE DEATH MOTIF IN THE LOVE POEMS OF THEODORE ROETHKE by George Wendt A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 1980 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to acknowledge my indebtedness to my readers, Dr. William R. Hiebel, Dr. Anthony S. LaBranche and Dr. Joseph J. Wolff. Their criticism helped me improve my dissertation. I would also like to thank Mrs. Beatrice Roethke Lushington for the insights she shared with me. Last, I am most grateful to my wife Anne for more patience and support than any husband could ever deserve. ii VITA The author, George Frederick Wendt, is the son of William Henry Wendt, Jr.,and Virginia Hauf Wendt. He was born on October 3, 1947, in Chicago, Illinois. -

RILKE and the MODERNIST TRADITION: a BRIEF LOOK at “ARCHAIC TORSO of ••• APOLLO”* Pyeaam ABBASI**

Uluslararası Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi The Journal of International Social Research Cilt: 6 Sayı: 24 Volume: 6 Issue: 24 Kış 2013 Winter 2013 www.sosyalarastirmalar.com Issn: 1307-9581 RILKE AND THE MODERNIST TRADITION: A BRIEF LOOK AT “ARCHAIC TORSO OF ••• APOLLO”* Pyeaam ABBASI** Abstract The twentieth century is associated with drastic changes as well as disintegration of old beliefs and grand narratives. Modern poets felt that it was high time they searched for new potentialities of language and made changes in form in order to express and explore changes the world was experiencing. The oneness of the world within and the world without is not peculiar to Rilke. He explores human consciousness as well as the interaction between human and the non-human world. This paper argues that his poetry is an invitation to the reader to participate and create. In “Archaic Torso of Apollo” the transfixed poet finds the torso full of life and vitality, a complete work of art and suggestive of the modernist tradition. As a modern poet Rilke would see the world within and the world without as the same aspects of each other. He believes that existence consists of interactions between things and the perceiving selves and that the inner world, familiar to our consciousness, is continuous with, even identical to, the material world we think of as exterior to our conscious selves. The interaction between the poet (subject) and the torso (subject) creates the sense of transformation. The article concludes that transformation seems to be the most critical change that the modern man needs to experience in the chaotic and disjointed world of the 20 th century. -

Rainer Maria Rilke Letters to a Young Poet

From Soulard’s Notebooks Assistant Editor: Kassandra Soulard To Seek a Better World [New Fiction] by G.C. Dillon 1 Poetry by Joe Coleman 5 Notes from New England [Commentary] by Raymond Soulard, Jr. 10 Manifest Project: June 2013 23 Poetry by Nathan D. Horowitz 44 Poetry by Tom Sheehan 49 Simian Songs [Essay] by Charlie Beyer 55 Poetry by Judih Haggai 59 Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke 63 Many Musics [Poetry] by Raymond Soulard, Jr. 87 Artist Gallery by Joe Coleman 100 The State of Psychedelic Research: Interview with Rick Doblin by Ido Hartogsohn 105 Poetry by Joe Ciccone 115 Poetry by Martina Newberry 116 Labyrinthine [A New Fixtion] by Raymond Soulard, Jr. 119 Notes on Contributors 156 2013 Front cover art by Joe Coleman. Back cover art by Raymond Soulard, Jr. & Kassandra Soulard. Original Cenacle logo by Barbara Brannon. Interior graphic artwork by Raymond Soulard, Jr. & Kassandra Soulard, exept where otherwise indicated. Manifest Project III is successor to Manifest Project I (Cenacle | 65 | June 2008) & Manifest Project II (Cenacle | 72 | April 2010). Accompanying disk to print version contains: • Cenacles #47-85 • Burning Man Books #1-66 • Scriptor Press Sampler #1-13 • RaiBooks #1-7 • RS Mixes from “Within’s Within: Scenes from the Psychedelic Revolution”; & • Jellicle Literary Guild Highlights Series Disk contents downloadable at: http://www.scriptorpress.com/cenacle/supplementary_disk. zip The Cenacle is published quarterly (with occasional special issues) by Scriptor Press New England, 2442 NW Market Street, #363, Seattle, Washington, 98107. It is kin organ to ElectroLounge website (http://www.scriptorpress.com), RaiBooks, Burning Man Books, Scriptor Press Sampler, The Jellicle Literary Guild, & “Within’s Within: Scenes from the Psychedelic Revolution w/Soulard,” broadcast online worldwide weekends on SpiritPlants Radio (http://www.spiritplantsradio.com). -

MY GERMANY Graham Mummery Talk Delivered at Ludwig Maximillian University, Munich, Friday 2Nd July 2010 at W-Orte Festival

MY GERMANY Graham Mummery Talk delivered at Ludwig Maximillian University, Munich, Friday 2nd July 2010 at W-Orte Festival I am going to talk to you about my experience of Germany, its language and culture. For clar- ity, I add that when I speak of Germany, or German, I include much that is from outside that geographical and political entity we know as Germany. For example composers such as Mo- zart and Schubert who came from Austria, or writers like Kafka and Rilke, who came from Prague count as German within this definition. This means we are talking about a Germany of my imagination. With its borders so defined, let’s enter. My first awareness of Germany comes in early childhood. My oldest friend, has a German mother. This is prob- ably my first awareness ofany country other my own, and that there might be different languages to English. My friend’s mother comes from Hamlin on the Wese, the town with the story of the Pied Piper, which I remember be- ing read to me from a book of fairy stories, which also included others like Hansel and Gretal and Rumplestiltskin which were written down by the Bothers Grimm. In the book, there were pictures of white castles, like those built by Ludwig II here in Bavaria. One way or another, Germany has been in my imagination from very early. My next glimpse comes through music. In the nineteenth century, Germans visiting Britain called it “Das Land ohne Musik.” An injustice, maybe, but with some truth in it. It was long before an Englishman became Director of the Berlin Philharmonic. -

(#) Indicates That This Book Is Available As Ebook Or E

ADAMS, ELLERY 11.Indigo Dying 6. The Darling Dahlias and Books by the Bay Mystery 12.A Dilly of a Death the Eleven O'Clock 1. A Killer Plot* 13.Dead Man's Bones Lady 2. A Deadly Cliché 14.Bleeding Hearts 7. The Unlucky Clover 3. The Last Word 15.Spanish Dagger 8. The Poinsettia Puzzle 4. Written in Stone* 16.Nightshade 9. The Voodoo Lily 5. Poisoned Prose* 17.Wormwood 6. Lethal Letters* 18.Holly Blues ALEXANDER, TASHA 7. Writing All Wrongs* 19.Mourning Gloria Lady Emily Ashton Charmed Pie Shoppe 20.Cat's Claw 1. And Only to Deceive Mystery 21.Widow's Tears 2. A Poisoned Season* 1. Pies and Prejudice* 22.Death Come Quickly 3. A Fatal Waltz* 2. Peach Pies and Alibis* 23.Bittersweet 4. Tears of Pearl* 3. Pecan Pies and 24.Blood Orange 5. Dangerous to Know* Homicides* 25.The Mystery of the Lost 6. A Crimson Warning* 4. Lemon Pies and Little Cezanne* 7. Death in the Floating White Lies Cottage Tales of Beatrix City* 5. Breach of Crust* Potter 8. Behind the Shattered 1. The Tale of Hill Top Glass* ADDISON, ESME Farm 9. The Counterfeit Enchanted Bay Mystery 2. The Tale of Holly How Heiress* 1. A Spell of Trouble 3. The Tale of Cuckoo 10.The Adventuress Brow Wood 11.A Terrible Beauty ALAN, ISABELLA 4. The Tale of Hawthorn 12.Death in St. Petersburg Amish Quilt Shop House 1. Murder, Simply Stitched 5. The Tale of Briar Bank ALLAN, BARBARA 2. Murder, Plain and 6. The Tale of Applebeck Trash 'n' Treasures Simple Orchard Mystery 3. -

Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann

Naharaim 2014, 8(2): 210–226 Uri Ganani and Dani Issler The World of Yesterday versus The Turning Point: Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann “A turning point in world history!” I hear people saying. “The right moment, indeed, for an average writer to call our attention to his esteemed literary personality!” I call that healthy irony. On the other hand, however, I wonder if a turning point in world history, upon careful consideration, is not really the moment for everyone to look inward. Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man1 Abstract: This article revisits the world-views of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann by analyzing the diverse ways in which they shaped their literary careers as autobiographers. Particular focus is given to the crises they experienced while composing their respective autobiographical narratives, both published in 1942. Our re-evaluation of their complex discussions on literature and art reveals two distinctive approaches to the relationship between aesthetics and politics, as well as two alternative concepts of authorial autonomy within society. Simulta- neously, we argue that in spite of their different approaches to political involve- ment, both authors shared a basic understanding of art as an enclave of huma- nistic existence at a time of oppressive political circumstances. However, their attitudes toward the autonomy of the artist under fascism differed greatly. This is demonstrated mainly through their contrasting portrayals of Richard Strauss, who appears in both autobiographies as an emblematic genius composer. DOI 10.1515/naha-2014-0010 1 Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, trans. -

The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage

The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage Phoebe S. Spinrad Ohio State University Press Columbus Copyright© 1987 by the Ohio State University Press. All rights reserved. A shorter version of chapter 4 appeared, along with part of chapter 2, as "The Last Temptation of Everyman, in Philological Quarterly 64 (1985): 185-94. Chapter 8 originally appeared as "Measure for Measure and the Art of Not Dying," in Texas Studies in Literature and Language 26 (1984): 74-93. Parts of Chapter 9 are adapted from m y "Coping with Uncertainty in The Duchess of Malfi," in Explorations in Renaissance Culture 6 (1980): 47-63. A shorter version of chapter 10 appeared as "Memento Mockery: Some Skulls on the Renaissance Stage," in Explorations in Renaissance Culture 10 (1984): 1-11. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Spinrad, Phoebe S. The summons of death on the medieval and Renaissance English stage. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. English drama—Early modern and Elizabethan, 1500-1700—History and criticism. 2. English drama— To 1500—History and criticism. 3. Death in literature. 4. Death- History. I. Title. PR658.D4S64 1987 822'.009'354 87-5487 ISBN 0-8142-0443-0 To Karl Snyder and Marjorie Lewis without who m none of this would have been Contents Preface ix I Death Takes a Grisly Shape Medieval and Renaissance Iconography 1 II Answering the Summon s The Art of Dying 27 III Death Takes to the Stage The Mystery Cycles and Early Moralities 50 IV Death -

Franz Kafka's Transformations

Franz Kafka’s Transformations Andrew Barker ALONE amongst the contributions to the volume, this essay does not address a Scandinavian topic. The theme of transformation in Franz Kafka’s work and life does, however, allow us to recall that Peter Graves is himself a notable example of a changeling, having begun his career at Aberdeen University as a student of German under the venerable Professor Wilhelm (Willy) Witte. What is presented here may thus serve as a reminder of a world Peter inhabited long ago, before he morphed into the Scandinavian polymath we know and honour today. The impetus for the present contribution came from reading James Hawes’ exhilarating study Excavating Kafka (2008).1 This work was promptly written off by Klaus Wagenbach, the doyen of Kafka studies in Germany, who is quoted as saying: ‘Irgendein Dämel kommt daher, weiß nix und schreibt über Kafka’ (Jungen 2008).2 In defence of Wagenbach’s po-faced dismissal of a much younger, non-German scholar’s work, one might plead that his grasp of English was insufficient for him to grasp the book’s satirical and polemical intentions. In fact, Excavating Kafka is the work of a scholar who knows a great deal about Kafka, and writes about him with panache and insight. I can match Hawes neither in my knowledge of Kafka nor the secondary literature, but I share with him a mounting frustration with the commonly-peddled myths about Kafka’s life and work, and it is some of these which I shall address in this short paper. Looking at the work first, I shall concentrate on what is probably Kafka’s most iconic story, Die Verwandlung (1912; ‘Metamorphosis’), the English translation of whose title I find particularly problematic. -

View Was Provided by the National Endowment for the Arts

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. JON HENDRICKS NEA Jazz Master (1993) Interviewee: Jon Hendricks (September 16, 1921 – November 22, 2017) and, on August 18, his wife Judith Interviewer: James Zimmerman with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: August 17-18, 1995 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 95 pp. Zimmerman: Today is August 17th. We’re in Washington, D.C., at the National Portrait Galley. Today we’re interviewing Mr. Jon Hendricks, composer, lyricist, playwright, singer: the poet laureate of jazz. Jon. Hendricks: Yes. Zimmerman: Would you give us your full name, the birth place, and share with us your familial history. Hendricks: My name is John – J-o-h-n – Carl Hendricks. I was born September 16th, 1921, in Newark, Ohio, the ninth child and the seventh son of Reverend and Mrs. Willie Hendricks. My father was a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the AME Church. Zimmerman: Who were your brothers and sisters? Hendricks: My brothers and sisters chronologically: Norman Stanley was the oldest. We call him Stanley. William Brooks, WB, was next. My sister, the oldest girl, Florence Hendricks – Florence Missouri Hendricks – whom we called Zuttie, for reasons I never For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 really found out – was next. Then Charles Lancel Hendricks, who is surviving, came next. Stuart Devon Hendricks was next. Then my second sister, Vivian Christina Hendricks, was next. -

The Sam Eskin Collection, 1939-1969, AFC 1999/004

The Sam Eskin Collection, 1939 – 1969 AFC 1999/004 Prepared by Sondra Smolek, Patricia K. Baughman, T. Chris Aplin, Judy Ng, and Mari Isaacs August 2004 Library of Congress American Folklife Center Washington, D. C. Table of Contents Collection Summary Collection Concordance by Format Administrative Information Provenance Processing History Location of Materials Access Restrictions Related Collections Preferred Citation The Collector Key Subjects Subjects Corporate Subjects Music Genres Media Formats Recording Locations Field Recording Performers Correspondents Collectors Scope and Content Note Collection Inventory and Description SERIES I: MANUSCRIPT MATERIAL SERIES II: SOUND RECORDINGS SERIES III: GRAPHIC IMAGES SERIES IV: ELECTRONIC MEDIA Appendices Appendix A: Complete listing of recording locations Appendix B: Complete listing of performers Appendix C: Concordance listing original field recordings, corresponding AFS reference copies, and identification numbers Appendix D: Complete listing of commercial recordings transferred to the Motion Picture, Broadcast, and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress 1 Collection Summary Call Number: AFC 1999/004 Creator: Eskin, Sam, 1898-1974 Title: The Sam Eskin Collection, 1938-1969 Contents: 469 containers; 56.5 linear feet; 16,568 items (15,795 manuscripts, 715 sound recordings, and 57 graphic materials) Repository: Archive of Folk Culture, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: This collection consists of materials gathered and arranged by Sam Eskin, an ethnomusicologist who recorded and transcribed folk music he encountered on his travels across the United States and abroad. From 1938 to 1952, the majority of Eskin’s manuscripts and field recordings document his growing interest in the American folk music revival. From 1953 to 1969, the scope of his audio collection expands to include musical and cultural traditions from Latin America, the British Isles, the Middle East, the Caribbean, and East Asia. -

Télécharger Le Dossier De Presse

HAPPINESS & PYRAMIDE présentent CARLA ALBRECHT ABRAHAM ROXANE JOEL STANLEY JURI SCHUCH DURAN BASMAN WEBER FESTIVAL DU FILM DE LOCARNO Piazza Grande RÉALISÉ PAR CHRISTIAN SCHWOCHOW D’APRÈS UN SCÉNARIO DE STEFAN KOLDITZ ET STEPHAN SUSCHKE AVEC CARLA JURI, ALBRECHT ABRAHAM SCHUCH, ROXANE DURAN, JOEL BASMAN, STANLEY WEBER, NICKI VON TEMPELHOFF, JONAS FRIEDRICH LEONHARDI, ‘‘ PAULA ’’ CASTING ANJA DIHRBERG DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE TIM PANNEN COSTUMES FRAUKE FIRL MAQUILLAGE & COIFFURE ASTRID WEBER HANNAH FISCHLEDER SON RAINER HEESCH, BRUNO TARRIERE, JEAN-PAUL BERNARD MUSIQUE JEAN RONDEAU MONTAGE JENS KLÜBER DIRECTEUR DE LA PHOTOGRAPHIE FRANCK LAMM DIRECTEUR DE PRODUCTION KATJA CHRISTOCHOWITZ PRODUCTEURS ASSOCIÉS BARBARA BUHL (WDR), CAROLIN HAASIS (DEGETO) ANNETTE STRELOW (RADIO BREMEN), ADREAS SCHREITMÜLLER (ARTE) CO-PRODUCTEURS LAURENCE CLERC, OLIVIER THERY LAPINEY PRODUCTEURS INGELORE KÖNIG, CHRISTOPH FRIEDEL, CLAUDIA STEFFEN SCÉNARISTES STEFAN KOLDITZ, STEPHEN SUSCHKE RÉALISATEUR CHRISTIAN SCHWOCHOW THE MATCH FACTORY PRÉSENTE UNE PRODUCTION PANDORA FILM PRODUKTION, GROWN UP FILMS EN COPRODUCTION AVEC ALCATRAZ FILMS ET WESTDEUTSCHER RUNDFUNK DEGETO RADIO BREMEN EN ASSOCIATION AVEC PANDORA FILM VERLEIH AVEC LE SOUTIEN DE FILM-UND MEDIENSTIFTUNG NRW DEUTSCHER FILMFÖRDERFONDSDOSSIER FILMFÖRDERUNGSANSTALT, MITTELDEUTSCHE MEDIENFÖRDERUNG DE NORDMEDIA,PRESSE DIE BEAUFTRAGTE DER BUNDESREGIERUNG FÜR KULTUR UND MEDIEN, CENTRE NATIONAL DU CINEMA ET DE L’IMAGE ANIMEE SORTIE LE 1ER MARS Durée : 2h03 Allemagne / France - 123 minutes - Audio 5.1 - Format 1: 2.39 - Allemand Titre original : Paula, Mein Leben soll ein Fest sein SYNOPSIS 1900, Nord de l’Allemagne. Paula Becker a 24 ans et veut la liberté, la gloire, le droit de jouir de son corps, et peindre avant tout. Malgré l’amour et l’admiration de son mari, le peintre Otto Modersohn, le manque de reconnaissance la pousse à tout quitter pour Paris, la ville des artistes. -

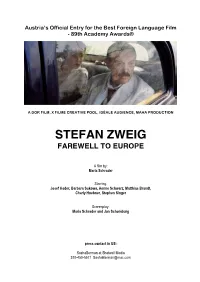

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant,