Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cronyism and Capital Controls: Evidence from Malaysia

Journal of Financial Economics 00 (2002) 000-000 Cronyism and capital controls: evidence from Malaysia Simon Johnsona,* Todd Mittonb aSloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA bMarriott School, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA (Received 24 August 2001; accepted 25 January 2002) Abstract The onset of the Asian financial crisis in Malaysia reduced the expected value of government subsidies to politically connected firms, accounting for roughly 9% of the estimated $60 billion loss in their market value from July 1997 to August 1998. Firing the Deputy Prime Minister and imposing capital controls in September 1998 primarily benefited firms with strong ties to Prime Minister Mahathir, accounting for roughly 32% of these firms’ estimated $5 billion gain in market value during September 1998. The evidence suggests Malaysian capital controls provided a screen behind which favored firms could be supported. JEL classification: G15; G38; F31 Keywords: Capital controls; Political connections; Financial crises; Institutions Johnson thanks the MIT Entrepreneurship Center for support. We thank Jim Brau for help with the SDC data. For helpful comments we thank an anonymous referee, Daron Acemoglu, Olivier Blanchard, Jim Brau, Ricardo Caballero, Ray Fisman, Tarun Khanna, Grant McQueen, Randall Morck, Sendhil Mullainathan, Raghuram Rajan, Dani Rodrik, David Scharfstein, Andrei Shleifer, Jeremy Stein, Keith Vorkink, Bernard Yeung, and participants at the MIT Macroeconomics lunch, the NBER conference on the Malaysian Currency Crisis, the NBER corporate finance program spring 2001 meeting, and the Brigham Young University finance seminar. We also thank several Malaysian colleagues for sharing their insights off the record. *Corresponding author contact information: Sloan School at MIT, Cambridge, MA 02142 E-mail: [email protected] 0304-405X/02/ $ see front matter © 2002 Published by Elsevier Science B.V. -

Laporan Tahunan Annual Report

LAPORAN ANNUAL TAHUNAN 2012 REPORT The corporate logo comprises the word BERJAYA in gold and a symbol made up of closely interwoven Bs in rich cobalt blue with gold lining around the circumference and a gold dot in the centre. BERJAYA means “success” in Bahasa Malaysia and reflects the success and Malaysian character of Berjaya Corporation’s core businesses. The intertwining Bs of the symbol represent our strong foundations and the constant synergy taking place within the Berjaya Corporation group of companies. Each B faces a different direction, depicting the varied strengths of the companies that make up the Berjaya Corporation group of companies. 01 Corporate Profile CONTENTS 02 Corporate Information 03 Profile of Directors 10 Chairman’s Statement and Review of Operations 46 Corporate Structure 48 Group Financial Summary 49 Group Financial Highlights 50 Statement on Corporate Governance 56 Statement on Internal Control 58 Audit Committee Report 61 Financial Statements 222 List of Properties 241 Material Contracts 241 Additional Information 242 Group Addresses 246 Recurrent Related Party Transactions of a Revenue or Trading Nature 252 Statement of Directors’ Shareholdings 254 Statistics on Shares and Convertible Securities 262 Notice of Annual General Meeting Form of Proxy Salt Pool - The Chateau Spa & Organic Wellness Resort, Berjaya Hills, Pahang. The Taaras Beach & Spa Resort, Redang Interior - Savanna Condominium, Island, Terengganu. Bukit Jalil, Kuala Lumpur. Garden Villas, Hanoi, Vietnam. CoRPoRAte PRofiLe The Berjaya Corporation group of companies’ history dates back to 1984 when the Founder, Tan Sri Dato’ Seri Vincent Tan Chee Yioun acquired a major controlling stake in Berjaya Industrial Berhad (originally known as Berjaya Kawat Berhad and now known as Reka Pacific Berhad) from the founders, Broken Hill Proprietary Ltd, Australia and National Iron & Steel Mills, Singapore. -

Curricullum Vitae

CURRICULLUM VITAE Name : YM Tunku Dato’ Yaacob Khyra Date, Place of Birth : 17 September 1960, Kuala Lumpur Nationality : Malaysian Age : 59 YM Tunku Dato’ Yaacob Khyra, is a prominent Malaysian business man, heading several public listed companies as chairman and as their major shareholder, via his family owned Melewar Khyra group of companies. As a member of the Negeri Sembilan royal family, his activities also include leading a number of non-profit and charitable organisations in Malaysia. 1.0 CURRENT BUSINESS ACTIVITIES Tunku conducts his business through his family holding company’s interest in the following public listed companies in Malaysia: Public Listed Company Indirect Interest Principal Activities MAA Group Berhad 40.05% Investment and management in the insurance, finance, education, lifestyle and technology sectors. Melewar Industrial Group 45.84% Investment and management in the Berhad steel and food sectors. Indirectly, Tunku is also deemed interested in the following Public Listed Company: Public Listed Company Indirect Interest Principal Activities Mycron Steel Berhad 74.15% A subsidiary of Melewar Industrial Group Bhd, Mycron manufactures quality Flat Steel Sheets known as Cold Rolled Coil (CRC) used by the downstream auto, oil & chemical drum, electrical white goods, furniture, roofing sheet, galvanizing and steel tube industries. The company also manufactures Steel Pipes and Tubes used by the construction, furniture, electrical, and water industries. 1 2.0 CURRENT BOARD REPRESENTATIONS Tunku currently sits as director in the following public listed company related corporations: Companies Interest Principal Activities Ithmaar Holdings B.S.C. 0% Financial services group, listed in Bahrain and Kuwait, involved mainly in banks in Bahrain and Pakistan, and insurance in the Gulf area. -

Annual Report 2019 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 CONTENTS The corporate logo comprises the word BERJAYA 01 Corporate Profile in gold and a symbol made up of closely interwoven 02 Corporate Information Bs in rich cobalt blue with gold lining around the circumference and a gold dot in the centre. 03 Profile of Directors 08 Key Senior Management BERJAYA means “success” in Bahasa Malaysia 11 Executive Chairman’s Message and reflects the success and Malaysian character of Berjaya Corporation’s core businesses. The 14 Management Discussion and Analysis intertwining Bs of the symbol represent our strong 30 Corporate Structure foundations and the constant synergy taking place within the Berjaya Corporation group of companies. 32 Group Financial Summary Each B faces a different direction, depicting the 33 Group Financial Highlights varied strengths of the companies that make up the Berjaya Corporation group of companies. 34 Sustainability Statement 59 Corporate Governance Overview Statement 74 Statement on Risk Management and VISION Internal Control 77 Audit Committee Report • To be an organisation which nurtures and carries on profitable and sustainable businesses in line with the 83 Statement of Directors’ Responsibility Group’s diverse business development and value in Respect of The Audited Financial creation aspirations and interests of all its stakeholders. Statements • To also be an organisation which maximises the value 84 Financial Statements of human capital through empowerment, growth and a 340 Material Properties of the Group commitment to excellence. 344 Material -

Off Pitch: Football's Financial Integrity Weaknesses, and How to Strengthen

Off Pitch: Football’s financial integrity weaknesses, and how to strengthen them Matt Andrews and Peter Harrington CID Working Paper No. 311 January 2016 Copyright 2016 Andrews, Matt; Harrington, Peter; and the President and Fellows oF Harvard College Working Papers Center for International Development at Harvard University Off Pitch: Football’s financial integrity weaknesses, and how to strengthen them Matt Andrews and Peter Harrington1 Abstract Men’s professional football is the biggest sport in the world, producing (by our estimate) US $33 billion a year. All is not well in the sector, however, with regular scandals raising questions about the role of money in the sport. The 2015 turmoil around FIFA is obviously the most well known example, creating a crisis in confidence in the sector. This study examines these questions, and the financial integrity weaknesses they reveal; it also offers ideas to strengthen the weaknesses. The study argues that football’s financial integrity weaknesses extend far beyond FIFA. These weaknesses have emerged largely because the sector is dominated by a small elite of clubs, players and owners centered in Europe’s top leagues. The thousands of clubs beyond this elite have very little resources, constituting a vast base of ‘have-nots’ in football’s financial pyramid. This pyramid developed in recent decades, fuelled by concentrated growth in new revenue sources (like sponsorships, and broadcasting). The growth has also led to increasingly complex transactions—in player transfers, club ownership and financing (and more)—and an expansion in opportunities for illicit practices like match-fixing, money laundering and human trafficking. We argue that football’s governing bodies – including FIFA – helped establish this pyramid. -

HA Marmay11 Mainsection.Pdf

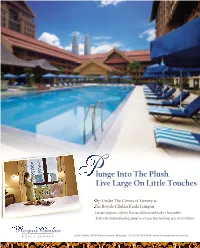

hospitality asia ~ March-May 2011 Page IFC C M Y K hospitality asia ~ March-May 2011 Page 1 C M Y K NOTE PUBLISHER’S ROAR OF THE FINEST While I am always wistful when it comes to comparing the Singapore hospitality experience to that of my home country, I know that other Southeast Asian properties are looking at Singapore guardedly as well. They have good reason to. After all, Singapore will play host to the Hospitality Asia Platinum Awards 2011-2013, with Capella Singapore hosting the Welcome Dinner on November 17 2011, and Mandarin Orchard Singapore hosting the Gala Dinner the next night. I know Singapore well enough to boldly say that both dinner events will be amazing. There is also a fine crop of nominees from the Lion City for HAPA Regional 2011- 2013. I am very pleased to say that instead of shrinking and cautiously watching the action from the sidelines, other Southeast Asian properties have boldly put in their bids to compete with the best of the best. Apart from Singapore and Malaysia, HAPA Regional will see the usual suspects from Thailand (Bangkok and Phuket) and Indonesia (Jakarta and Bali). The new participating cities are Koh Samui, Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, Bintan, Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh and Manila as well. What a series it is going to be! As my team and I continue to endeavour to lift the standards of Southeast Asian hospitality on a whole, we also look to our own publication with the view of improving. We continue to refine the product, fuelled by feedback from not only the suppliers which this publication initially served, but also the increasing number of first class and business travellers who enjoy our content on some of the best airlines in the world. -

Dewan Rakyat

Bil. 21 Isnin 19 April 2010 MALAYSIA PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIMEN KEDUA BELAS PENGGAL KETIGA MESYUARAT PERTAMA K A N D U N G A N RANG UNDANG-UNDANG DIBAWA KE DALAM MESYUARAT (Halaman 1) RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Perbekalan Tambahan (2010) 2010 Jawatankuasa:- Jadual:- Maksud B.22 (Halaman 2) Maksud B.23 (Halaman 12) Maksud B.24 (Halaman 13) Maksud B.25 (Halaman 20) Maksud B.27 (Halaman 41) Maksud B.28 (Halaman 28) Maksud B.29 (Halaman 71) Maksud B.31 (Halaman 79) Maksud B.41 (Halaman 96) Maksud B.42 (Halaman 122) Maksud B.49 (Halaman 131) Maksud B.60 (Halaman 136) Maksud B.62 (Halaman 143) USUL-USUL: Waktu Mesyuarat dan Urusan Dibebaskan Daripada Peraturan Mesyuarat (Halaman 1) Anggaran Pembangunan Tambahan (Bil.1) 2010 Jawatankuasa:- Maksud P.22 (Halaman 2) Maksud P.24 (Halaman 13) Maksud P.28 (Halaman 28) Maksud P.31 (Halaman 79) Maksud P.62 (Halaman 143) Meminda Jadual Di Bawah P.M. 66(9) – Memotong RM10 Peruntukan Kepala B.41 (Halaman 96) Diterbitkan Oleh: CAWANGAN PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN MALAYSIA 2010 DR.19.4.2010 i AHLI-AHLI DEWAN RAKYAT 1. Yang Berhormat Tuan Yang di-Pertua, Tan Sri Datuk Seri Utama Pandikar Amin Haji Mulia, S.U.M.W., P.G.D.K., P.S.M., J.S.M., J.P. 2. Yang Berhormat Timbalan Yang di-Pertua, Datuk Dr. Haji Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar, P.J.N., P.B.S. J.B.S., J.S.M. (Santubong) – PBB 3. “ Timbalan Yang di-Pertua, Datuk Ronald Kiandee, A.S.D.K., P.G.D.K. -

THE NEW ECONOMIC POLICY and the UNITED MALAYS NATIONAL ORGANIZATION —With Special Reference to the Restructuring of Malaysian Society—

The Developing Economies, XXXV-3 (September 1997): 209–39 THE NEW ECONOMIC POLICY AND THE UNITED MALAYS NATIONAL ORGANIZATION —With Special Reference to the Restructuring of Malaysian Society— TAKASHI TORII INTRODUCTION N 1990, Malaysia duly completed its twenty-year New Economic Policy (NEP) which was launched in 1971. Though the NEP has been described as I an “economic” policy, its contents and implementation processes show that it went far beyond the scope of economic policy packages. In fact, policies in such noneconomic areas as education, language, culture, and religion have been formu- lated and implemented in close relationships with it. Consequently, the NEP has exerted major influences not only on Malaysia’s economy but on Malaysian society as a whole. From the point of view of the NEP’s stated objective, namely, “ to lift up the economic and social status of Malays,” the NEP has achieved signal successes, such as the creation of a Malay middle class and Malay entrepreneurs, most notably the new Malay business groups.1 A number of both positive and negative evaluations have been made about the NEP, which has had such a major impact on Malaysian society.2 These studies generally identify two basic characteristics of the NEP. –––––––––––––––––––––––––– This paper is part of the fruits of the research and investigation I conducted in Malaysia in 1991–93 as a visiting research fellow at the National University of Malaysia (Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia— UKM). I wish to express my gratitude to the Institute of Developing Economies for sending me out as its research fellow, the National University of Malaysia for accepting and helping me, and the UMNO Research Bureau and the New Straits Times Research Centre for giving me the opportunity to use their valuable archives. -

Tan Sri Dato' Seri Vincent Tan Recognised for His

Berjaya Corporation Berhad’s Quarterly Newsletter - Issue 1, 2016 KDN No : PP 7432/02/2013(031932) On 16 March 2016, the President of Kiwanis International Foundation TAN SRI DATO’ SERI VINCENT (“KIF”), Mr Mark B. Rabaut paid a courtesy visit to Tan Sri Dato’ Seri Vincent Tan (“TSVT”), Founder of Berjaya Corporation group of companies and presented him with a legacy lead gift donor medallion and a token of TAN RECOGNISED FOR HIS appreciation in recognition of his contribution totaling to approximately CONTRIBUTION TO KIWANIS US$200,000 towards The Eliminate Project. TSVT is one of the two lead donors in Asia Pacific who have donated more than US$100,000 towards the project. With this contribution, INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION approximately 110,000 mothers and babies would be vaccinated and protected from tetanus disease. Also present were Datuk Fatimah Saad, Governor of Kiwanis Malaysia; Hwang Chia Sing, Treasurer of KIF; Lee Kuan Yong, Chairman of Kiwanis Asia Pacific and Dato’ Sri Robin Tan, Chairman and CEO of Berjaya Corporation Berhad. The Eliminate Project is a global health campaign by KIF in partnership with UNICEF to eliminate maternal and neonatal tetanus (“MNT”) disease. The project aims to raise US$110 million and save the lives of 129 million mothers and their future babies. As of February 2016, KIF has raised US$107 million in cash and pledges. MNT is among the most common lethal consequences of unclean deliveries and umbilical cord care practices. When tetanus develops, mortality rates are extremely high, especially when appropriate medical care is not available. This happens despite the fact that MNT deaths can be easily prevented by hygienic delivery and cord care practices, and/ or by immunizing mothers with tetanus vaccine that is cheap and very efficacious. -

2Nd Berjaya Youth Stop Hunger Now Meal Packing Event, RM100

PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release 2nd BERJAYA YOUTH - STOP HUNGER NOW MEAL PACKING EVENT RM100,000 worth of meals for people in critical need Kuala Lumpur, 10 October 2015 – Berjaya Youth (“B.Youth”), a youth empowerment initiative by Berjaya Corporation Berhad, and Stop Hunger Now Charitable Association of Malaysia (“Stop Hunger Now”), an international hunger relief organization, joined forces to organise a volunteer-based meal packing event for the second consecutive year at Berjaya Times Square KL. B.Youth and Stop Hunger Now had chosen to hold this meal packing event around this time of the year to commemorate the World Food Day which is observed worldwide on 16th October annually to raise awareness of the issues and challenges surrounding malnutrition, hunger and poverty. To make today’s meal packing event a reality, B.Youth roped in approximately 400 volunteers. Out of these volunteers, close to 300 of them were staff of Berjaya Group of Companies, while the others were proactive youths who signed up through Berjaya Youth’s Facebook page as well as volunteers from Nalanda Buddhist Society and Bandar Utama Dhamma Duta Youth. A total of RM100,000 worth of meals were packed and handed over to: (1) Rotary Club of Kota Kinabalu South which is providing relief support to victims of the mud floods and landslides following the earthquake in Ranau, Sabah in June this year; (2) Yayasan Orang Kurang Upaya Kelantan for the handicapped children and adults of extremely poor background in Kelantan who are suffering from malnutrition; (3) Sarawak Dayak Iban Association for the underprivileged among the Dayak Iban ethnic group in Sarawak; and (4) Malaysian Red Crescent Society for the Orang Asli community in the rural parts of Pahang, Kelantan and Perak in anticipation of the monsoon season. -

The Media and Poverty in Malaysia

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Portraying the poor : the media and poverty in Malaysia Zaharom Nain. 1999 Zaharom Nain. (1999). Portraying the poor : the media and poverty in Malaysia. In Seminar on Media and Human Rights Reporting on Asia's Rural Poor : November 24‑26, 1999, Bangkok. Singapore: Asian Media Information and Communication Centre. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/93229 Downloaded on 04 Oct 2021 18:53:24 SGT ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library Paper No. 5 ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library Portraying the Poor: The Media and Poverty in Malaysia Zaharom Nain Universiti Sains Malaysia 1999 1. The State and Poverty: Malaysia's Post-Independence Development Policies The contemporary Malaysian population is multi-ethnic and multi-religious, with three major ethnic groups - Malay, Chinese and Indian - and numerous other ethnic minorities (including Iban, Kadazan, Bajau and Murut), particularly located in East Malaysia. According to 1997 estimates (Bank Negara Malaysia Annual Report, 1996), Malaysia has a total population of 21.7 million. Of these, more than 17 million (78.3 per cent of the total population) are located in Peninsular Malaysia. And the ethnic composition of this 17 million is as follows: 9.8 million (57.7 per cent) are Bumiputera (Malay and certain other indigenous groups), 4.6 million (27.1 per cent) are Chinese, and 1.5 million (8.8 per cent) are Indian. Given its multi-ethnic nature, not surprisingly, Malaysia's history1 has been dominated by ethnic-based parties and ethnic politics since it attained independence. -

Annual Report 2019 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 CONTENTS The corporate logo comprises the word BERJAYA 01 Corporate Profile in gold and a symbol made up of closely interwoven 02 Corporate Information Bs in rich cobalt blue with gold lining around the circumference and a gold dot in the centre. 03 Profile of Directors 08 Key Senior Management BERJAYA means “success” in Bahasa Malaysia 11 Executive Chairman’s Message and reflects the success and Malaysian character of Berjaya Corporation’s core businesses. The 14 Management Discussion and Analysis intertwining Bs of the symbol represent our strong 30 Corporate Structure foundations and the constant synergy taking place within the Berjaya Corporation group of companies. 32 Group Financial Summary Each B faces a different direction, depicting the 33 Group Financial Highlights varied strengths of the companies that make up the Berjaya Corporation group of companies. 34 Sustainability Statement 59 Corporate Governance Overview Statement 74 Statement on Risk Management and VISION Internal Control 77 Audit Committee Report • To be an organisation which nurtures and carries on profitable and sustainable businesses in line with the 83 Statement of Directors’ Responsibility Group’s diverse business development and value in Respect of The Audited Financial creation aspirations and interests of all its stakeholders. Statements • To also be an organisation which maximises the value 84 Financial Statements of human capital through empowerment, growth and a 340 Material Properties of the Group commitment to excellence. 344 Material