The Timing, Layering, Comagmatic Basalt Flows, Granophyres, Trondhjemites, and Magma Source of the Palisades Intrusive System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecosystem Flow Recommendations for the Delaware River Basin

Ecosystem Flow Recommendations for the Delaware River Basin Report to the Delaware River Basin Commission Upper Delaware River © George Gress Submitted by The Nature Conservancy December 2013 THE NATURE CONSERVANCY Ecosystem Flow Recommendations for the Delaware River Basin December 2013 Report prepared by The Nature Conservancy Michele DePhilip Tara Moberg The Nature Conservancy 2101 N. Front St Building #1, Suite 200 Harrisburg, PA 17110 Phone: (717) 232‐6001 E‐mail: Michele DePhilip, [email protected] Suggested citation: DePhilip, M. and T. Moberg. 2013. Ecosystem flow recommendations for the Delaware River basin. The Nature Conservancy. Harrisburg, PA. Table of Contents Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................. iii Project Summary ................................................................................................................................... iv Section 1: Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Project Description and Goals ............................................................................................... 1 1.2 Project Approach ........................................................................................................................ 2 Section 2: Project Area and Basin Characteristics .................................................................... 6 2.1 Project Area ................................................................................................................................. -

Igneous Processes During the Assembly and Breakup of Pangaea: Northern New Jersey and New York City

IGNEOUS PROCESSES DURING THE ASSEMBLY AND BREAKUP OF PANGAEA: NORTHERN NEW JERSEY AND NEW YORK CITY CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS AND FIELD GUIDE EDITED BY Alan I. Benimoff GEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF NEW JERSEY XXX ANNUAL CONFERENCE AND FIELDTRIP OCTOBER 11 – 12, 2013 At the College of Staten Island, Staten Island, NY IGNEOUS PROCESSES DURING THE ASSEMBLY AND BREAKUP OF PANGAEA: NORTHERN NEW JERSEY AND NEW YORK CITY CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS AND FIELD GUIDE EDITED BY Alan I. Benimoff GEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF NEW JERSEY XXX ANNUAL CONFERENCE AND FIELDTRIP OCTOBER 11 – 12, 2013 COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND, STATEN ISLAND, NY i GEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF NEW JERSEY 2012/2013 EXECUTIVE BOARD President .................................................. Alan I. Benimoff, PhD., College of Staten Island/CUNY Past President ............................................... Jane Alexander PhD., College of Staten Island/CUNY President Elect ............................... Nurdan S. Duzgoren-Aydin, PhD., New Jersey City University Recording Secretary ..................... Stephen J Urbanik, NJ Department of Environmental Protection Membership Secretary ..............................................Suzanne Macaoay Ferguson, Sadat Associates Treasurer ............................................... Emma C Rainforth, PhD., Ramapo College of New Jersey Councilor at Large………………………………..Alan Uminski Environmental Restoration, LLC Councilor at Large ............................................................ Pierre Lacombe, U.S. Geological Survey Councilor at Large ................................. -

Potential On-Shore and Off-Shore Reservoirs for CO2 Sequestration in Central Atlantic Magmatic Province Basalts

Potential on-shore and off-shore reservoirs for CO2 sequestration in Central Atlantic magmatic province basalts David S. Goldberga, Dennis V. Kenta,b,1, and Paul E. Olsena aLamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, 61 Route 9W, Palisades, NY 10964; and bEarth and Planetary Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854. Contributed by Dennis V. Kent, November 30, 2009 (sent for review October 16, 2009) Identifying locations for secure sequestration of CO2 in geological seafloor (16) may offer potential solutions to these additional formations is one of our most pressing global scientific problems. issues that are more problematic on land. Deep-sea aquifers Injection into basalt formations provides unique and significant are fully saturated with seawater and typically capped by imper- advantages over other potential geological storage options, includ- meable sediments. The likelihood of postinjection leakage of ing large potential storage volumes and permanent fixation of car- CO2 to the seafloor is therefore low, reducing the potential bon by mineralization. The Central Atlantic Magmatic Prov- impact on natural and human ecosystems (8). Long after CO2 ince basalt flows along the eastern seaboard of the United States injection, the consequences of laterally displaced formation water may provide large and secure storage reservoirs both onshore and to distant locations and ultimately into the ocean, whether by offshore. Sites in the South Georgia basin, the New York Bight engineered or natural outflow systems, are benign. For more than basin, and the Sandy Hook basin offer promising basalt-hosted a decade, subseabed CO2 sequestration has been successfully reservoirs with considerable potential for CO2 sequestration due conducted at >600 m depth in the Utsira Formation as part of to their proximity to major metropolitan centers, and thus to large the Norweigan Sleipner project (17). -

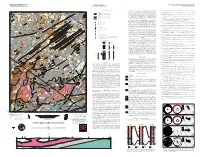

Bedrock Geologic Map of the Monmouth Junction Quadrangle, Water Resources Management U.S

DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Prepared in cooperation with the BEDROCK GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE MONMOUTH JUNCTION QUADRANGLE, WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SOMERSET, MIDDLESEX, AND MERCER COUNTIES, NEW JERSEY NEW JERSEY GEOLOGICAL AND WATER SURVEY NATIONAL GEOLOGIC MAPPING PROGRAM GEOLOGICAL MAP SERIES GMS 18-4 Cedar EXPLANATION OF MAP SYMBOLS cycle; lake level rises creating a stable deep lake environment followed by a fall in water level leading to complete Cardozo, N., and Allmendinger, R. W., 2013, Spherical projections with OSXStereonet: Computers & Geosciences, v. 51, p. 193 - 205, doi: 74°37'30" 35' Hill Cem 32'30" 74°30' 5 000m 5 5 desiccation of the lake. Within the Passaic Formation, organic-rick black and gray beds mark the deep lake 10.1016/j.cageo.2012.07.021. 32 E 33 34 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 490 000 FEET 542 40°30' 40°30' period, purple beds mark a shallower, slightly less organic-rich lake, and red beds mark a shallow oxygenated 6 Contacts 100 M Mettler lake in which most organic matter was oxidized. Olsen and others (1996) described the next longer cycle as the Christopher, R. A., 1979, Normapolles and triporate pollen assemblages from the Raritan and Magothy formations (Upper Cretaceous) of New 6 A 100 I 10 N Identity and existance certain, location accurate short modulating cycle, which is made up of five Van Houten cycles. The still longer in duration McLaughlin cycles Jersey: Palynology, v. 3, p. 73-121. S T 44 000m MWEL L RD 0 contain four short modulating cycles or 20 Van Houten cycles (figure 1). -

THE JOURNAL of GEOLOGY March 1990

VOLUME 98 NUMBER 2 THE JOURNAL OF GEOLOGY March 1990 QUANTITATIVE FILLING MODEL FOR CONTINENTAL EXTENSIONAL BASINS WITH APPLICATIONS TO EARLY MESOZOIC RIFTS OF EASTERN NORTH AMERICA' ROY W. SCHLISCHE AND PAUL E. OLSEN Department of Geological Sciences and Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964 ABSTRACT In many half-graben, strata progressively onlap the hanging wall block of the basins, indicating that both the basins and their depositional surface areas were growing in size through time. Based on these con- straints, we have constructed a quantitative model for the stratigraphic evolution of extensional basins with the simplifying assumptions of constant volume input of sediments and water per unit time, as well as a uniform subsidence rate and a fixed outlet level. The model predicts (1) a transition from fluvial to lacustrine deposition, (2) systematically decreasing accumulation rates in lacustrine strata, and (3) a rapid increase in lake depth after the onset of lacustrine deposition, followed by a systematic decrease. When parameterized for the early Mesozoic basins of eastern North America, the model's predictions match trends observed in late Triassic-age rocks. Significant deviations from the model's predictions occur in Early Jurassic-age strata, in which markedly higher accumulation rates and greater lake depths point to an increased extension rate that led to increased asymmetry in these half-graben. The model makes it possible to extract from the sedimentary record those events in the history of an extensional basin that are due solely to the filling of a basin growing in size through time and those that are due to changes in tectonics, climate, or sediment and water budgets. -

2020 Natural Resources Inventory

2020 NATURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY TOWNSHIP OF MONTGOMERY SOMERSET COUNTY, NEW JERSEY Prepared By: Tara Kenyon, AICP/PP Principal NJ License #33L100631400 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... 5 AGRICULTURE ............................................................................................................................................................. 7 AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY IN AND AROUND MONTGOMERY TOWNSHIP ...................................................... 7 REGULATIONS AND PROGRAMS RELATED TO AGRICULTURE ...................................................................... 11 HEALTH IMPACTS OF AGRICULTURAL AVAILABILITY AND LOSS TO HUMANS, PLANTS AND ANIMALS .... 14 HOW IS MONTGOMERY TOWNSHIP WORKING TO SUSTAIN AND ENHANCE AGRICULTURE? ................... 16 RECOMMENDATIONS AND POTENTIAL PROJECTS .......................................................................................... 18 CITATIONS ............................................................................................................................................................. 19 AIR QUALITY .............................................................................................................................................................. 21 CHARACTERISTICS OF AIR .................................................................................................................................. 21 -

To Middle Silurian) in Eastern Pennsylvania

The Shawangunk Formation (Upper OrdovicianC?) to Middle Silurian) in Eastern Pennsylvania GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 744 Work done in cooperation with the Pennsylvania Depa rtm ent of Enviro nm ental Resources^ Bureau of Topographic and Geological Survey The Shawangunk Formation (Upper Ordovician (?) to Middle Silurian) in Eastern Pennsylvania By JACK B. EPSTEIN and ANITA G. EPSTEIN GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 744 Work done in cooperation with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources, Bureau of Topographic and Geological Survey Statigraphy, petrography, sedimentology, and a discussion of the age of a lower Paleozoic fluvial and transitional marine clastic sequence in eastern Pennsylvania UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1972 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 74-189667 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 65 cents (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-2098 CONTENTS Page Abstract _____________________________________________ 1 Introduction __________________________________________ 1 Shawangunk Formation ___________________________________ 1 Weiders Member __________ ________________________ 2 Minsi Member ___________________________________ 5 Lizard Creek Member _________________________________ 7 Tammany Member _______________________________-_ 12 Age of the Shawangunk Formation _______ __________-___ 14 Depositional environments and paleogeography _______________ 16 Measured sections ______________________________________ 23 References cited ________________________________________ 42 ILLUSTRATIONS Page FIGURE 1. Generalized geologic map showing outcrop belt of the Shawangunk Formation in eastern Pennsylvania and northwestern New Jersey ___________________-_ 3 2. Stratigraphic section of the Shawangunk Formation in the report area ___ 3 3-21. Photographs showing 3. Conglomerate and quartzite, Weiders Member, Lehigh Gap ____ 4 4. -

Drainage Patterns

Drainage Patterns Over time, a stream system achieves a particular drainage pattern to its network of stream channels and tributaries as determined by local geologic factors. Drainage patterns or nets are classified on the basis of their form and texture. Their shape or pattern develops in response to the local topography and Figure 1 Aerial photo illustrating subsurface geology. Drainage channels develop where surface dendritic pattern in Gila County, AZ. runoff is enhanced and earth materials provide the least Courtesy USGS resistance to erosion. The texture is governed by soil infiltration, and the volume of water available in a given period of time to enter the surface. If the soil has only a moderate infiltration capacity and a small amount of precipitation strikes the surface over a given period of time, the water will likely soak in rather than evaporate away. If a large amount of water strikes the surface then more water will evaporate, soaks into the surface, or ponds on level ground. On sloping surfaces this excess water will runoff. Fewer drainage channels will develop where the surface is flat and the soil infiltration is high because the water will soak into the surface. The fewer number of channels, the coarser will be the drainage pattern. Dendritic drainage pattern A dendritic drainage pattern is the most common form and looks like the branching pattern of tree roots. It develops in regions underlain by homogeneous material. That is, the subsurface geology has a similar resistance to weathering so there is no apparent control over the direction the tributaries take. -

Flat Rock Brook” This Stream Flows Downhill Over the Eroded Flat Surfaces of the Diabase Basalt Forming the Palisades

“Flat Rock Brook” This stream flows downhill over the eroded flat surfaces of the diabase basalt forming the Palisades. It drains into Crystal Lake and Overpeck Creek as part of the Hackensack River watershed. Flat Rock Brook flows down from the top of the Palisades beginning in Englewood Cliffs The brook empties into Crystal Lake and now continues in culverts beneath Interstate 80/95 to Overpeck Creek, a tributary of the Hackensack River watershed. The “flat rocks” are diabase basalts at the top of an igneous intrusion, the Palisades Sill. (See “The Seven Sisters” for more information.) They formed underground about 200 million years ago. The diabase was more resistant to erosion than the overlying sedimentary rocks. Over time, the overlying rocks were removed by erosion, exposing the flat diabase surface. Earthquakes tilted the region, producing the westward slope characterizing the East Hill section of Englewood down to Grand Ave. and Engle St. On the eastern side of the sill, erosion and rock falls created the cliffs of the Palisades along the Hudson River. This 1880s map shows part of Flat Rock Brook. The pond labelled “Vanderbeck’s Mill Pond” was created by damming the brook in 1876. It was later known as Macfadden’s Pond. https://www.flatrockbrook.org/about-us/history In the 1970s, the Englewood Nature Association (now the Flat Rock Brook Nature Association) was established to preserve the area, resulting in establishment of the Flat Rock Brook Nature Center. Green Acres funding from the State of New Jersey was important in beginning this project. In the 1980s, it was merged with Allison Park, creating the 150-acre preserve in existence today. -

Drainage Basin Morphology in the Central Coast Range of Oregon

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF WENDY ADAMS NIEM for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in GEOGRAPHY presented on July 21, 1976 Title: DRAINAGE BASIN MORPHOLOGY IN THE CENTRAL COAST RANGE OF OREGON Abstract approved: Redacted for privacy Dr. James F. Lahey / The four major streams of the central Coast Range of Oregon are: the westward-flowing Siletz and Yaquina Rivers and the eastward-flowing Luckiamute and Marys Rivers. These fifth- and sixth-order streams conform to the laws of drain- age composition of R. E. Horton. The drainage densities and texture ratios calculated for these streams indicate coarse to medium texture compa- rable to basins in the Carboniferous sandstones of the Appalachian Plateau in Pennsylvania. Little variation in the values of these parameters occurs between basins on igneous rook and basins on sedimentary rock. The length of overland flow ranges from approximately i mile to i mile. Two thousand eight hundred twenty-five to 6,140 square feet are necessary to support one foot of channel in the central Coast Range. Maximum elevation in the area is 4,097 feet at Marys Peak which is the highest point in the Oregon Coast Range. The average elevation of summits in the thesis area is ap- proximately 1500 feet. The calculated relief ratios for the Siletz, Yaquina, Marys, and Luckiamute Rivers are compara- ble to relief ratios of streams on the Gulf and Atlantic coastal plains and on the Appalachian Piedmont. Coast Range streams respond quickly to increased rain- fall, and runoff is rapid. The Siletz has the largest an- nual discharge and the highest sustained discharge during the dry summer months. -

The Water' Cycle

'I ." Name'~~_~__-,,__....,......,....,......, ~ Class --,-_......,...._------,__ Date ....,......,-.:-_ ..: .•..'-' .. M.ODERN EARTH SCIENCE Section 1s.i The Water' Cycle • Read each statement below. If the statement .ls true, write T in the space provided. If the statement is false, write Fin tbe space provided. -'- 1. The hydrologic cycle is also called the water cycle. 2. Most water evaporating from the earth's surface evaporates from rivers and lakes. 3. When water vapor rises in the atmosphere, it expands and cools. 4. Evapotranspiration increases with increasing temperature. 5. Most water used by industry is recycled. 6. Irrigation is often necessary in areas having high evapotranspiration. Cboose the one best response. Write tbe letter of tbat cboice in tbe space provided. 7. Which of the following is an artificial means of producing fresh water from ocean water? .--i a. desalination b. saltation • c. evapotranspiration d. condensation 8. Which of the following is represented by this diagram? a. the earth's water budget b. local water budget . c. groundwater movement -·d. surface runoff 9. The arrow labeled X represents: a. absorption. b. evaporation.. c. rejuvenation. d. transpiration. _ 10. Approximately what percentage of the earth's precipitation falls-on the ocean? a. 5% b. 25% c. 750/0 d. 99% t • Chapter 13 47 l H_R_w_..._"_ter"_:_al_....._p_yrighted undernotice appearing earlier in thisworic. .'. Name _ Class _ Date - MODERN EARTH SCIENCE .... '''; ... .secti~n'· if2 River Systems Choose the one best response. Write the letter of that choice in the space provided. 1. What is the term for the main stream and tributaries of a river? a. -

How the Gap Formed

Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area How the Gap formed What is a water gap? Several words in the English language The Delaware Water Gap is justly famous for denote a “break” or “cleft” in the moun- its depth, width, and scenic beauty. The Gap tains. Chasm and notch are popular in New is a mile wide from New Jersey’s Mount England; pass and gorge in the South and Tammany (1,527 feet) to Pennsylvania’s West of the United States. Gap is especially Mount Minsi (1,463 feet.) The Gap is about common in this part of the country. 1,200 feet deep from the tops of these mountains to the surface of the river, which A gap or wind gap is a break or pass through at this point is 290 feet above sea level. The the mountains, in this case the Appalachian maximum depth of the river at the Gap is Mountains. A water gap is a pass that a river about 55 feet. runs through. How does a gap form? Geology is the study of the earth’s forma- Starting with Native American legend, there tion. Though the geologist’s time frame may have been many ideas about how the seem vast and remote, the results of Delaware Water Gap formed. One current geological processes are the mountains we theory explains the Gap through a series of hike on, the river we swim in, and the processes: continental shift (involving plate scenery we admire. tectonics), mountain building (orogeny), erosion, and the “capturing” of rivers and streams.