Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecosystem Flow Recommendations for the Delaware River Basin

Ecosystem Flow Recommendations for the Delaware River Basin Report to the Delaware River Basin Commission Upper Delaware River © George Gress Submitted by The Nature Conservancy December 2013 THE NATURE CONSERVANCY Ecosystem Flow Recommendations for the Delaware River Basin December 2013 Report prepared by The Nature Conservancy Michele DePhilip Tara Moberg The Nature Conservancy 2101 N. Front St Building #1, Suite 200 Harrisburg, PA 17110 Phone: (717) 232‐6001 E‐mail: Michele DePhilip, [email protected] Suggested citation: DePhilip, M. and T. Moberg. 2013. Ecosystem flow recommendations for the Delaware River basin. The Nature Conservancy. Harrisburg, PA. Table of Contents Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................. iii Project Summary ................................................................................................................................... iv Section 1: Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Project Description and Goals ............................................................................................... 1 1.2 Project Approach ........................................................................................................................ 2 Section 2: Project Area and Basin Characteristics .................................................................... 6 2.1 Project Area ................................................................................................................................. -

Delaware River Restoration Fund 2018 Grant Slate

Delaware River Restoration Fund 2018 Grant Slate NFWF CONTACTS Rachel Dawson Program Director, Delaware River [email protected] 202-595-2643 Jessica Lillquist Coordinator, Delaware River [email protected] 202-595-2612 PARTNERS • The William Penn Foundation • U.S. Forest Service • U.S. Department of Agriculture (NRCS) • American Forest Foundation To learn more, go to www.nfwf.org/delaware ABOUT NFWF Delaware River flowing through the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area | Credit: Jim Lukach The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) protects and OVERVIEW restores our nation’s fish and The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) and The William Penn Foundation wildlife and their habitats. Created by Congress in 1984, NFWF directs public conservation announced the fifth-year round of funding for the Delaware River Restoration Fund dollars to the most pressing projects. Thirteen new or continuing water conservation and restoration grants totaling environmental needs and $2.2 million were awarded, drawing $3.5 million in match from grantees and generating a matches those investments total conservation impact of $5.7 million. with private funds. Learn more at www.nfwf.org As part of the broader Delaware River Watershed Initiative, the William Penn Foundation provided $6 million in grant funding for NFWF to continue to administer competitively NATIONAL HEADQUARTERS through its Delaware River Restoration Fund in targeted regions throughout the 1133 15th Street, NW Delaware River watershed for the next three years. This year, NFWF is also beginning to Suite 1000 award grants that address priorities in its new Delaware River Watershed Business Plan. Washington, D.C., 20005 Delaware River Restoration Fund grants are multistate investments to restore habitats 202-857-0166 and deliver practices that ultimately improve(continued) and protect critical sources of drinking water. -

. Hikes at The

Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area Hikes at the Gap Pennsylvania (Mt. Minsi) 4. Resort Point Spur to Appalachian Trail To Mt. Minsi PA from Kittatinny Point NJ This 1/4-mile blue-blazed trail begins across Turn right out of the visitor center parking lot. 1. Appalachian Trail South to Mt. Minsi (white blaze) Follow signs to Interstate 80 west over the river Route 611 from Resort Point Overlook (Toll), staying to the right. Take PA Exit 310 just The AT passes through the village of Delaware Water Gap (40.978171 -75.138205) -- cross carefully! -- after the toll. Follow signs to Rt. 611 south, turn to Mt. Minsi/Lake Lenape parking area (40.979754 and climbs up to Lake Lenape along a stream right at the light at the end of the ramp; turn left at -75.142189) off Mountain Rd.The trail then climbs 1-1/2 that once ran through the basement of the next light in the village; turn right 300 yards miles and 1,060 ft. to the top of Mt. Minsi, with views Kittatinny Hotel. (Look in the parking area for later at Deerhead Inn onto Mountain Rd. About 0.1 mile later turn left onto a paved road with an over the Gap and Mt. Tammany NJ. the round base of the hotel’s fountain.) At the Appalachian Trail (AT) marker to the parking top, turn left for views of the Gap along the AT area. Rock 2. Table Rock Spur southbound, or turn right for a short walk on Cores This 1/4-mile spur branches off the right of the Fire Road the AT northbound to Lake Lenape parking. -

NJGS Contracted with Greater New York City Through the Borough of Richmond President Cromwell, to Provide Water for 1835 Staten Island

UNEARTHING NEW JERSEY NEW JERSEY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Vol. 5, No. 2 Summer 2009 Department of Environmental Protection MESSAGE FROM THE STATE GEOLOGIST A PLAN TO PLUNDER NEW JERSEY’S WATER This issue of Unearthing New Jersey continues the series of historic stories with Mark French’s article A Plan to Plunder New Jersey’s Water. This story concerns a plan by By Mark French the Hudson County Water Company and its myriad political allies to divert an enormous portion of the water resources of INTRODUCTION New Jersey to the City of New York. The scheme was driven At the turn of the 20th century, potable water in New by the desire for private gain at the expense of the citizens of Jersey was managed by private companies or municipalities New Jersey. Thanks to the swift action of the Legislature, the through special grants from the State Legislature or State Attorney General, the State Geologist and the highest certificates of incorporation granted by the State under the courts in the land, the Hudson County Water Company General Incorporation Law of 1875. Clamoring for oversight, plot was stymied setting a riparian rights precedent in the the citizenry and the Legislature tried to create a State process. Water Commission in 1894, but the effort was quashed by A second historic article, The New York-New Jersey Line water business interests and their friends in the Legislature. War by Ted Pallis, Mike Girard and Walt Marzulli discusses Companies were mostly free to traffic in water as they saw the geographic boundaries of New Jersey. -

Climate Change, Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area Patrick Gonzalez

Climate Change, Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area Patrick Gonzalez Abstract Greenhouse gas emissions from human activities have caused global climate change and widespread impacts on physical systems, ecosystems, and biodiversity. To assist in the integration of climate change science into resource management in Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area (NRA), particularly the proposed restoration of wetlands at Watergate, this report presents: (1) results of original spatial analyses of historical and projected climate trends at 800 m spatial resolution, (2) results of a systematic scientific literature review of historical impacts, future vulnerabilities, and carbon, focusing on research conducted in the park, and (3) results of original spatial analyses of precipitation in the Vancampens Brook watershed, location of the Watergate wetlands. Average annual temperature from 1950 to 2010 increased at statistically significant rates of 1.1 ± 0.5ºC (2 ± 0.9ºF.) per century (mean ± standard error) for the area within park boundaries and 0.9 ± 0.4ºC (1.6 ± 0.7ºF.) per century for the Vancampens Brook watershed. The greatest temperature increase in the park was in spring. Total annual precipitation from 1950 to 2010 showed no statistically significant change. Few analyses of field data from within or near the park have detected historical changes that have been attributed to human climate change, although regional analyses of bird counts from across the United States (U.S.) show that climate change shifted winter bird ranges northward 0.5 ± 0.3 km (0.3 ± 0.2 mi.) per year from 1975 to 2004. With continued emissions of greenhouse gases, projections under the four emissions scenarios of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicate annual average temperature increases of up to 5.2 ± 1ºC (9 ± 2º F.) (mean ± standard deviation) from 2000 to 2100 for the park as a whole. -

To Middle Silurian) in Eastern Pennsylvania

The Shawangunk Formation (Upper OrdovicianC?) to Middle Silurian) in Eastern Pennsylvania GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 744 Work done in cooperation with the Pennsylvania Depa rtm ent of Enviro nm ental Resources^ Bureau of Topographic and Geological Survey The Shawangunk Formation (Upper Ordovician (?) to Middle Silurian) in Eastern Pennsylvania By JACK B. EPSTEIN and ANITA G. EPSTEIN GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 744 Work done in cooperation with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources, Bureau of Topographic and Geological Survey Statigraphy, petrography, sedimentology, and a discussion of the age of a lower Paleozoic fluvial and transitional marine clastic sequence in eastern Pennsylvania UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1972 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 74-189667 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 65 cents (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-2098 CONTENTS Page Abstract _____________________________________________ 1 Introduction __________________________________________ 1 Shawangunk Formation ___________________________________ 1 Weiders Member __________ ________________________ 2 Minsi Member ___________________________________ 5 Lizard Creek Member _________________________________ 7 Tammany Member _______________________________-_ 12 Age of the Shawangunk Formation _______ __________-___ 14 Depositional environments and paleogeography _______________ 16 Measured sections ______________________________________ 23 References cited ________________________________________ 42 ILLUSTRATIONS Page FIGURE 1. Generalized geologic map showing outcrop belt of the Shawangunk Formation in eastern Pennsylvania and northwestern New Jersey ___________________-_ 3 2. Stratigraphic section of the Shawangunk Formation in the report area ___ 3 3-21. Photographs showing 3. Conglomerate and quartzite, Weiders Member, Lehigh Gap ____ 4 4. -

Drainage Patterns

Drainage Patterns Over time, a stream system achieves a particular drainage pattern to its network of stream channels and tributaries as determined by local geologic factors. Drainage patterns or nets are classified on the basis of their form and texture. Their shape or pattern develops in response to the local topography and Figure 1 Aerial photo illustrating subsurface geology. Drainage channels develop where surface dendritic pattern in Gila County, AZ. runoff is enhanced and earth materials provide the least Courtesy USGS resistance to erosion. The texture is governed by soil infiltration, and the volume of water available in a given period of time to enter the surface. If the soil has only a moderate infiltration capacity and a small amount of precipitation strikes the surface over a given period of time, the water will likely soak in rather than evaporate away. If a large amount of water strikes the surface then more water will evaporate, soaks into the surface, or ponds on level ground. On sloping surfaces this excess water will runoff. Fewer drainage channels will develop where the surface is flat and the soil infiltration is high because the water will soak into the surface. The fewer number of channels, the coarser will be the drainage pattern. Dendritic drainage pattern A dendritic drainage pattern is the most common form and looks like the branching pattern of tree roots. It develops in regions underlain by homogeneous material. That is, the subsurface geology has a similar resistance to weathering so there is no apparent control over the direction the tributaries take. -

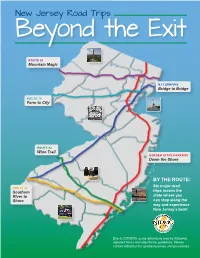

Beyond the Exit

New Jersey Road Trips Beyond the Exit ROUTE 80 Mountain Magic NJ TURNPIKE Bridge to Bridge ROUTE 78 Farm to City ROUTE 42 Wine Trail GARDEN STATE PARKWAY Down the Shore BY THE ROUTE: Six major road ROUTE 40 Southern trips across the River to state where you Shore can stop along the way and experience New Jersey’s best! Due to COVID19, some attractions may be following adjusted hours and attendance guidelines. Please contact attraction for updated policies and procedures. NJ TURNPIKE – Bridge to Bridge 1 PALISADES 8 GROUNDS 9 SIX FLAGS CLIFFS FOR SCULPTURE GREAT ADVENTURE 5 6 1 2 4 3 2 7 10 ADVENTURE NYC SKYLINE PRINCETON AQUARIUM 7 8 9 3 LIBERTY STATE 6 MEADOWLANDS 11 BATTLESHIP PARK/STATUE SPORTS COMPLEX NEW JERSEY 10 OF LIBERTY 11 4 LIBERTY 5 AMERICAN SCIENCE CENTER DREAM 1 PALISADES CLIFFS - The Palisades are among the most dramatic 7 PRINCETON - Princeton is a town in New Jersey, known for the Ivy geologic features in the vicinity of New York City, forming a canyon of the League Princeton University. The campus includes the Collegiate Hudson north of the George Washington Bridge, as well as providing a University Chapel and the broad collection of the Princeton University vista of the Manhattan skyline. They sit in the Newark Basin, a rift basin Art Museum. Other notable sites of the town are the Morven Museum located mostly in New Jersey. & Garden, an 18th-century mansion with period furnishings; Princeton Battlefield State Park, a Revolutionary War site; and the colonial Clarke NYC SKYLINE – Hudson County, NJ offers restaurants and hotels along 2 House Museum which exhibits historic weapons the Hudson River where visitors can view the iconic NYC Skyline – from rooftop dining to walk/ biking promenades. -

Delaware Water Gap U.S

National Park Service Delaware Water Gap U.S. Department of the Interior National Recreation Area Summer/Fall 2015 Guide to the Gap N A YEARS A T E I 50 1965-2015 R O A N N AL IO RECREAT Your National Park Celebrates 50 Years! The Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area was established by a park for the people. Today, visitors roam a landscape carved by uplift, Congress on September 1, 1965, to preserve the natural, culture, and scenic erosion, and glacial activity that is marked by hemlock and rhododendron- resources of the Delaware River Valley and provide opportunities for laced ravines, rumbling waterfalls, fertile floodplains and is rich with recreation, education, and enjoyment to the most densely populated region archaeological evidence and historic narratives. This haven for natural of the nation. Sprung out of the Tocks Island Dam controversy, the last and cultural stories is your place, your park, and we invite you to celebrate 50 years has solidified Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area as with us in 2015. The River, the Valley, and You . 2 Events. 4 Delaware River . 6 Park Trails . 8. Fees and Passes . 2 Park Map and Visitor Centers . 3 Are you curious about the natural and cultural Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area From ridgetop to riverside, vistas to ravines, Activities and Events in 2015 . 4 history of the area? Would you like to see includes nearly 40 miles of the free-flowing from easy to extreme, more than 100 Delaware River Water Trail . 6 artisans at work? Want to experience what it Middle Delaware River Scenic and Recreational miles of trail offer something for every mood. -

Drainage Basin Morphology in the Central Coast Range of Oregon

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF WENDY ADAMS NIEM for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in GEOGRAPHY presented on July 21, 1976 Title: DRAINAGE BASIN MORPHOLOGY IN THE CENTRAL COAST RANGE OF OREGON Abstract approved: Redacted for privacy Dr. James F. Lahey / The four major streams of the central Coast Range of Oregon are: the westward-flowing Siletz and Yaquina Rivers and the eastward-flowing Luckiamute and Marys Rivers. These fifth- and sixth-order streams conform to the laws of drain- age composition of R. E. Horton. The drainage densities and texture ratios calculated for these streams indicate coarse to medium texture compa- rable to basins in the Carboniferous sandstones of the Appalachian Plateau in Pennsylvania. Little variation in the values of these parameters occurs between basins on igneous rook and basins on sedimentary rock. The length of overland flow ranges from approximately i mile to i mile. Two thousand eight hundred twenty-five to 6,140 square feet are necessary to support one foot of channel in the central Coast Range. Maximum elevation in the area is 4,097 feet at Marys Peak which is the highest point in the Oregon Coast Range. The average elevation of summits in the thesis area is ap- proximately 1500 feet. The calculated relief ratios for the Siletz, Yaquina, Marys, and Luckiamute Rivers are compara- ble to relief ratios of streams on the Gulf and Atlantic coastal plains and on the Appalachian Piedmont. Coast Range streams respond quickly to increased rain- fall, and runoff is rapid. The Siletz has the largest an- nual discharge and the highest sustained discharge during the dry summer months. -

Delaware Water Gap

Delaware Water Gap NATIONAL RECREATION AREA PENNSYLVANIA . NEW JERSEY WHERE TO STAY Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, completed facilities are not yet in operation at terrace at the foot of Mount Minsi near the lower authorized by Congress in 1965, will preserve a a particular site, plan to return when you can end of the parking area, there is an unobstructed Food, lodging, gasoline, souvenirs, and other large and relatively unspoiled area astride the visit in safety and comfort. view across the river. Exhibits at the terrace ex items are available in towns and communities river boundary of Pennsylvania and New Jersey. plain how this mountain range was formed and from Port Jervis, N. Y., at the upper end of the Within easy driving range of several large metro- help you to understand rock formations visible national recreation area, to Portland, Pa., a few KITTATINNY POINT is on the New Jersey side politan areas, it will provide facilities and in the side of Mount Tammany. These million-year- miles below the proposed dam. No camping or of the Water Gap between Int. 80 and the Dela services for many types of recreational activities old rocks are constantly being changed by the picnicking facilities are available in the area ware River. A parking overlook is at the foot of and for interpretation of the area's scenic, forces of erosion. Alternate freezing and thawing this season, but they are available in nearby Mount Tammany on the opposite side of the scientific, and historical values. The forest cover of water in the crevices and plants forcing their State and private developments. -

The Nature of Boulder-Rich Deposits in the Upper Big Flat Brook Drainage, Sussex County, New Jersey

Middle States Geographer, 2009, 42: 33-43 THE NATURE OF BOULDER-RICH DEPOSITS IN THE UPPER BIG FLAT BROOK DRAINAGE, SUSSEX COUNTY, NEW JERSEY Gregory A. Pope, Andrew J. Temples, Sean I. McLearie, Joanne C. Kornoelje, and Thomas J. Glynn Department of Earth & Environmental Studies Montclair State University 1 Normal Avenue Montclair, New Jersey, 07043 ABSTRACT: The upper reaches of the Big Flat Brook drainage, northwest of Kittatinny Mountain, contain a variety of glacial, pro-glacial, and periglacial deposits from the Late Quaternary. The area is dominated by recessional moraines and ubiquitous ground moraine, along with meltwater deposits, drumlins, and possible post- glacial periglacial features. We have identified a curious boulder-rich deposit in the vicinity of Lake Ocquittunk and Lake Wapalanne on upper Big Flat Brook. The area where these boulder deposits occur is mapped (1:24,000 surficial geology) as till. As mapped and observed, larger cobbles and boulders within the till are quartz-pebble conglomerate, quartzite, sandstone, and shale. The boulder-rich deposits differ from the typical till, however. Unlike the local till, which is more mixed in lithology, the boulder deposits are nearly exclusively Shawangunk conglomerate. The deposits are discontinuous, but appear to occur at a topographic level above the meltwater stream terraces. The boulders in the deposits lie partially embedded in soil, but are very closely spaced. The boulders range in size from ~20cm to over 100cm, and present a subrounded to subangular shape. There appears to be a fabric orientation of the boulders, NE-SW, with subsidiary orientations. As the boulder deposits differ from other mapped features in the area, we attempt to ascertain the origin for the deposits.