THE VICTORIAN CHANCELLORS Cf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winning the Right Way Standards of Busin Ess Co Nduct

Standards of business conduct Winning the right way Standards of busin ess co nduct Table o cont nts 4 HP Values 4 Core Principles 4 Leader Attributes 6 A message from Dian Weisler 6 A message from David Deitchman 7 Using the HP Standards of Business Conduct 9 The Headline Test 9 Unsure about a decision or action? 10 Building trust 10 We make ethical decisions 10 We take action when aware of misconduct and do not retaliate 10 We cooperate with investigations 11 Respect 11 We honor human rights 11 We treat others with respect 11 We maintain a safe and secure work environment 11 We promote and provide a harassment-free work environment 11 We respect privacy and protect personal information Standards of bus iness co nduct 12 Uncompromising integrity 12 We use assets wisely 12 We maintain accurate business records 12 We avoid conft.icts of interest 13 We provide and accept gifts and entertainment only when appropriate 13 We do not bribe or accept kickbacks 13 We protect sensitive information 14 We comply with laws governing international trade 14 We do not trade on or disclose nonpublic material information 15 Passion for customers 15 We provide quality products and services 15 We market responsibly 15 We compete vigorously and fairly 15 We obtain business intelligence appropriately 16 Responsible citizenship 16 We are stewards of the environment 16 We engage with responsible business partners and suppliers 17 We communicate honestly with investors and the media 17 We exercise our rights in the political process 17 We support giving and volunteering in our communities 18 Winning the right way, every day 19 Contacting the Ethics and Compliance Office Standards of business co nduct Since Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard started our company many years ago, HP has been known not just for the products and services we offer, but also for the values we share. -

The Rhinehart Collection Rhinehart The

The The Rhinehart Collection Spine width: 0.297 inches Adjust as needed The Rhinehart Collection at appalachian state university at appalachian state university appalachian state at An Annotated Bibliography Volume II John higby Vol. II boone, north carolina John John h igby The Rhinehart Collection i Bill and Maureen Rhinehart in their library at home. ii The Rhinehart Collection at appalachian state university An Annotated Bibliography Volume II John Higby Carol Grotnes Belk Library Appalachian State University Boone, North Carolina 2011 iii International Standard Book Number: 0-000-00000-0 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 0-00000 Carol Grotnes Belk Library, Appalachian State University, Boone, North Carolina 28608 © 2011 by Appalachian State University. All rights reserved. First Edition published 2011 Designed and typeset by Ed Gaither, Office of Printing and Publications. The text face and ornaments are Adobe Caslon, a revival by designer Carol Twombly of typefaces created by English printer William Caslon in the 18th century. The decorative initials are Zallman Caps. The paper is Carnival Smooth from Smart Papers. It is of archival quality, acid-free and pH neutral. printed in the united states of america iv Foreword he books annotated in this catalogue might be regarded as forming an entity called Rhinehart II, a further gift of material embodying British T history, literature, and culture that the Rhineharts have chosen to add to the collection already sheltered in Belk Library. The books of present concern, diverse in their -

Military Commander and the Law – 2019

THE MILITARY • 2019 COMMANDER AND THE THE LAW MILITARY THE MILITARY COMMANDER AND THE LAW TE G OCA ENE DV RA A L E ’S G S D C H U J O E O H L T U N E C IT R E D FO S R TATES AI The Military Commander and the Law is a publication of The Judge Advocate General’s School. This publication is used as a deskbook for instruction at various commander courses at Air University. It also serves as a helpful reference guide for commanders in the field, providing general guidance and helping commanders to clarify issues and identify potential problem areas. Disclaimer: As with any publication of secondary authority, this deskbook should not be used as the basis for action on specific cases. Primary authority, much of which is cited in this edition, should first be carefully reviewed. Finally, this deskbook does not serve as a substitute for advice from the staff judge advocate. Editorial Note: This edition was edited and published during the Secretary of the Air Force’s Air Force Directive Publication Reduction initiative. Therefore, many of the primary authorities cited in this edition may have been rescinded, consolidated, or superseded since publication. It is imperative that all authorities cited herein be first verified for currency on https://www.e-publishing.af.mil/. Readers with questions or comments concerning this publication should contact the editors of The Military Commander and the Law at the following address: The Judge Advocate General’s School 150 Chennault Circle (Bldg 694) Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6418 Comm. -

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This Collection Was the Gift of Howard J

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This collection was the gift of Howard J. Garber to Case Western Reserve University from 1979 to 1993. Dr. Howard Garber, who donated the materials in the Howard J. Garber Manuscript Collection, is a former Clevelander and alumnus of Case Western Reserve University. Between 1979 and 1993, Dr. Garber donated over 2,000 autograph letters, documents and books to the Department of Special Collections. Dr. Garber's interest in history, particularly British royalty led to his affinity for collecting manuscripts. The collection focuses primarily on political, historical and literary figures in Great Britain and includes signatures of all the Prime Ministers and First Lords of the Treasury. Many interesting items can be found in the collection, including letters from Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning Thomas Hardy, Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, King George III, and Virginia Woolf. Descriptions of the Garber Collection books containing autographs and tipped-in letters can be found in the online catalog. Box 1 [oversize location noted in description] Abbott, Charles (1762-1832) English Jurist. • ALS, 1 p., n.d., n.p., to ? A'Beckett, Gilbert A. (1811-1856) Comic Writer. • ALS, 3p., April 7, 1848, Mount Temple, to Morris Barnett. Abercrombie, Lascelles. (1881-1938) Poet and Literary Critic. • A.L.S., 1 p., March 5, n.y., Sheffield, to M----? & Hughes. Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon (1784-1860) British Prime Minister. • ALS, 1 p., June 8, 1827, n.p., to Augustous John Fischer. • ANS, 1 p., August 9, 1839, n.p., to Mr. Wright. • ALS, 1 p., January 10, 1853, London, to Cosmos Innes. -

Middlesex University Research Repository an Open Access Repository Of

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Farmer, Sandra Jean (1992) ’Trustees of posterity’: Benjamin Disraeli and the European Bildungsroman. PhD thesis, King’s College London. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/13473/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007 K - Z Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 A complete listing of all Fellows and Foreign Members since the foundation of the Society K - Z July 2007 List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 The list contains the name, dates of birth and death (where known), membership type and date of election for all Fellows of the Royal Society since 1660, including the most recently elected Fellows (details correct at July 2007) and provides a quick reference to around 8,000 Fellows. It is produced from the Sackler Archive Resource, a biographical database of Fellows of the Royal Society since its foundation in 1660. Generously funded by Dr Raymond R Sackler, Hon KBE, and Mrs Beverly Sackler, the Resource offers access to information on all Fellows of the Royal Society since the seventeenth century, from key characters in the evolution of science to fascinating lesser- known figures. In addition to the information presented in this list, records include details of a Fellow’s education, career, participation in the Royal Society and membership of other societies. Citations and proposers have been transcribed from election certificates and added to the online archive catalogue and digital images of the certificates have been attached to the catalogue records. This list is also available in electronic form via the Library pages of the Royal Society web site: www.royalsoc.ac.uk/library Contributions of biographical details on any Fellow would be most welcome. -

Gaslightpdffinal.Pdf

Credits. Book Layout and Design: Miah Jeffra Cover Artwork: Pseudodocumentation: Broken Glass by David DiMichele, Courtesy of Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco ISBN: 978-0-692-33821-6 The Writers Retreat for Emerging LGBTQ Voices is made possible, in part, by a generous contribution by Amazon.com Gaslight Vol. 1 No. 1 2014 Gaslight is published once yearly in Los Angeles, California Gaslight is exclusively a publication of recipients of the Lambda Literary Foundation's Emerging Voices Fellowship. All correspondence may be addressed to 5482 Wilshire Boulevard #1595 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Details at www.lambdaliterary.org. Contents Director's Note . 9 Editor's Note . 11 Lisa Galloway / Epitaph ..................................13 / Hives ....................................16 Jane Blunschi / Snapdragon ................................18 Miah Jeffra / Coffee Spilled ................................31 Victor Vazquez / Keiki ....................................35 Christina Quintana / A Slip of Moon ........................36 Morgan M Page / Cruelty .................................51 Wayne Johns / Where Your Children Are ......................53 Wo Chan / Our Majesties at Michael's Craft Shop ..............66 / [and I, thirty thousand feet in the air, pop] ...........67 / Sonnet by Lamplight ............................68 Yana Calou / Mortars ....................................69 Hope Thompson/ Sharp in the Dark .........................74 Yuska Lutfi Tuanakotta / Mother and Son Go Shopping ..........82 Megan McHugh / I Don't Need to Talk -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

![Complete Baronetage of 1720," to Which [Erroneous] Statement Brydges Adds](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5807/complete-baronetage-of-1720-to-which-erroneous-statement-brydges-adds-845807.webp)

Complete Baronetage of 1720," to Which [Erroneous] Statement Brydges Adds

cs CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 092 524 374 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924092524374 : Complete JSaronetage. EDITED BY Gr. Xtl. C O- 1^ <»- lA Vi «_ VOLUME I. 1611—1625. EXETER WILLIAM POLLAKD & Co. Ltd., 39 & 40, NORTH STREET. 1900. Vo v2) / .|vt POirARD I S COMPANY^ CONTENTS. FACES. Preface ... ... ... v-xii List of Printed Baronetages, previous to 1900 xiii-xv Abbreviations used in this work ... xvi Account of the grantees and succeeding HOLDERS of THE BARONETCIES OF ENGLAND, CREATED (1611-25) BY JaMES I ... 1-222 Account of the grantees and succeeding holders of the baronetcies of ireland, created (1619-25) by James I ... 223-259 Corrigenda et Addenda ... ... 261-262 Alphabetical Index, shewing the surname and description of each grantee, as above (1611-25), and the surname of each of his successors (being Commoners) in the dignity ... ... 263-271 Prospectus of the work ... ... 272 PREFACE. This work is intended to set forth the entire Baronetage, giving a short account of all holders of the dignity, as also of their wives, with (as far as can be ascertained) the name and description of the parents of both parties. It is arranged on the same principle as The Complete Peerage (eight vols., 8vo., 1884-98), by the same Editor, save that the more convenient form of an alphabetical arrangement has, in this case, had to be abandoned for a chronological one; the former being practically impossible in treating of a dignity in which every holder may (and very many actually do) bear a different name from the grantee. -

Operation London Bridge 2020

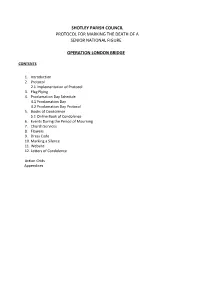

SHOTLEY PARISH COUNCIL PROTOCOL FOR MARKING THE DEATH OF A SENIOR NATIONAL FIGURE OPERATION LONDON BRIDGE CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Protocol 2.1 Implementation of Protocol 3. Flag Flying 4. Proclamation Day Schedule 4.1 Proclamation Day 4.2 Proclamation Day Protocol 5. Books of Condolence 5.1 Online Book of Condolence 6. Events During the Period of Mourning 7. Church Services 8. Flowers 9. Dress Code 10. Marking a Silence 11. Website 12. Letters of Condolence Action Grids Appendices 1. INTRODUCTION These guidance notes have been produced from those issued by the National Association of Civic Officers (NACO). They set out the protocols to which local Councils should follow and observe on marking the death of a senior national figure and to be observed on the death of the Sovereign, which involves the greatest number of ceremonial elements. From this template, it is possible to select elements that are appropriate when marking the death of, for instance, another member of the Royal Family, a Prime Minister or former Prime Minister, a serving Member of Parliament. All parts of this protocol apply on the death of the Sovereign (and, of course, those sections around the Accession Proclamation arise only on the Monarch’s death). Beyond that, implementation of the Protocol is a matter to be decided locally. This protocol offers guidance on how to mark a death. It is down to the Parish Chairman and Parish Clerk to decide for whom the protocol is implemented and to what extent. Flying of flag at half-mast will always be appropriate. Other decisions, -

The Lives of the Chief Justices of England

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com I . i /9& \ H -4 3 V THE LIVES OF THE CHIEF JUSTICES .OF ENGLAND. FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST TILL THE DEATH OF LORD TENTERDEN. By JOHN LOKD CAMPBELL, LL.D., F.E.S.E., AUTHOR OF 'THE LIVES OF THE LORd CHANCELLORS OF ENGL AMd.' THIRD EDITION. IN FOUE VOLUMES.— Vol. IT;; ; , . : % > LONDON: JOHN MUEEAY, ALBEMAELE STEEET. 1874. The right of Translation is reserved. THE NEW YORK (PUBLIC LIBRARY 150146 A8TOB, LENOX AND TILBEN FOUNDATIONS. 1899. Uniform with the present Worh. LIVES OF THE LOED CHANCELLOKS, AND Keepers of the Great Seal of England, from the Earliest Times till the Reign of George the Fourth. By John Lord Campbell, LL.D. Fourth Edition. 10 vols. Crown 8vo. 6s each. " A work of sterling merit — one of very great labour, of richly diversified interest, and, we are satisfied, of lasting value and estimation. We doubt if there be half-a-dozen living men who could produce a Biographical Series' on such a scale, at all likely to command so much applause from the candid among the learned as well as from the curious of the laity." — Quarterly Beview. LONDON: PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET AND CHARINg CROSS. CONTENTS OF THE FOURTH VOLUME. CHAPTER XL. CONCLUSION OF THE LIFE OF LOKd MANSFIELd. Lord Mansfield in retirement, 1. His opinion upon the introduction of jury trial in civil cases in Scotland, 3.