The Law and Highway Modernization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statutory Rape: a Guide to State Laws and Reporting Requirements

Statutory Rape: A Guide to State Laws and Reporting Requirements Prepared for: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Department of Health and Human Services Prepared by: Asaph Glosser Karen Gardiner Mike Fishman The Lewin Group December 15, 2004 Acknowledgements Work on this project was funded by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services under a contract to The Lewin Group. This report benefited greatly from the oversight and input of Jerry Silverman, the ASPE Project Officer. In addition, we would like to acknowledge the assistance of a number of reviewers. Sarah Brown, Eva Klain, and Brenda Rhodes Miller provided us with valuable guidance and insights into legal issues and the policy implications of the laws and reporting requirements. Their comments improved both the content and the organization of the paper. At The Lewin Group, Shauna Brodsky reviewed drafts and provided helpful comments. The Authors Table of Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..........................................................................................................ES-1 A. Background...........................................................................................................................ES-1 1. Criminal Laws............................................................................................................... ES-1 2. Reporting Requirements............................................................................................. -

Summary of State Speed Laws

DOT HS 810 826 August 2007 Summary of State Speed Laws Tenth Edition Current as of January 1, 2007 This document is available to the public from the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, Virginia 22161 This publication is distributed by the U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in the interest of information exchange. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Department of Transportation or the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. If trade or manufacturers' names or products are mentioned, it is because they are considered essential to the object of the publication and should not be construed as an endorsement. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................iii Missouri ......................................................138 Alabama..........................................................1 Montana ......................................................143 Alaska.............................................................5 Nebraska .....................................................150 Arizona ...........................................................9 Nevada ........................................................157 Arkansas .......................................................15 New -

Summary of Vehicle Occupant Protection Laws Ninth Edition Current As of June 1, 2010 DISCLAIMER

DOT HS 811 458 April 2011 Summary of Vehicle Occupant Protection Laws Ninth Edition Current as of June 1, 2010 DISCLAIMER This publication is distributed by the U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in the interest of information exchange. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Transportation or the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. If trade names, manufacturers’names, or specific products are mentioned, it is because they are considered essential to the object of the publication and should not be construed as an endorsement. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………. iii OVERVIEW NARRATIVE OF KEY PROVISIONS………………………………………….. v SUMMARY CHART OF KEY PROVISIONS…………………………………………………. vi ALABAMA……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 ALASKA………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 ARIZONA……………………………………………………………………………………….. 8 ARKANSAS…………………………………………………………………………………….. 11 CALIFORNIA…………………………………………………………………………………… 14 COLORADO…………………………………………………………………………………….. 19 CONNECTICUT………………………………………………………………………………… 22 DELAWARE…………………………………………………………………………………….. 26 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA…………………………………………………………………….. 29 FLORIDA………………………………………………………………………………………… 33 GEORGIA……………………………………………………………………………………….. 37 HAWAI’I………………………………………………………………………………………… -

Uniform Electronic Legal Material Act – Enactments June 2019

UNIFORM ELECTRONIC LEGAL MATERIAL ACT – ENACTMENTS JUNE 2019 STATE BILL NUMBER COVERED LEGAL MATERIALS FISCAL IMPACT ENACTED EFFECTIVE • Constitution of Arizona Arizona • Arizona session laws No fiscal impact SB 1414 5/17/2016 8/8/2016 • Arizona Revised Statutes $135,000 to $165,000 (General Fund) for set up, authentication, • California Constitution archiving, and onsite storage. California SB 1075 • California Statutes 9/13/2012 7/1/2015 • California Codes Annual ongoing costs in the range of $40,000 to $70,000. • Colorado Constitution • Session Laws of Colorado $198,912 4/26/2012 3/31/2014 Colorado HB 1209 • Colorado Revised Statutes • State agency rules with effect of law • Constitution of Connecticut • General Statutes of Connecticut Connecticut SB 235 • Regulations of Connecticut state agencies No fiscal impact 5/17/2013 10/1/2014 • Reported decisions of Connecticut Supreme Court, Connecticut Appellate Court, and Connecticut Superior Court • Constitution of Delaware • Delaware Laws of Delaware No fiscal impact HB 403 • Delaware Code 7/23/2014 10/21/2014 • Regulations published in the Delaware Administrative Code • Hawaii Constitution • Hawaii Session Laws • Hawaii Revised Statutes Hawaii • State agency rules with effect of law No fiscal impact SB 32 / HB 18 • Reported decisions of Supreme Court of 4/16/2013 7/1/2013 State of Hawaii and Intermediate Appellate Court of Hawaii • State court rules • Idaho Constitution • Idaho Session Laws • Idaho Code Idaho • Idaho Administrative Code and Administrative No fiscal impact S1356 Bulletin -

Survey of Federal & State Laws

Survey of Federal & State Laws: Understanding Your Right To Be Treated Fairly and Without Discriminaon in Restaurants, Stores, and Other Businesses PUBLIC ACCOMMODATION LAWS BASED ON RACE, COLOR, AND/OR NATIONAL ORIGIN Last Updated : September 20, 2020 ** This survey is provided solely for informaonal purposes. Stop AAPI Hate does not warrant the accuracy of the informaon contained herein. Users are encouraged to seek advice from a licensed aorney regarding potenal violaons of any applicable public accommodaon laws. ** CAVEATS (1) This survey reviews general public accommodaon statutes under federal law and the laws of the states and District of Columbia. A review of case law interpreng the scope and applicaon of these statutes as well as a review of other statutes that may provide general an-discriminaon protecons or other indirect legal protecons are beyond the scope of this survey. (2) The scope of public accommodaon statutes differ from jurisdicon to jurisdicon based on differences in how key terms are statutorily defined and the existence of different statutory exempons to the statutes. (3) Addional public accommodaon laws may exist at the local (sub-federal/state) level. A comprehensive survey of which localies have enacted such laws is beyond the scope of this survey. However, in jurisdicons where no statewide public accommodaon laws for individuals based on race, color, or naonal origin exist, an aempt has been made to determine whether local public accommodaon laws exist in major urban centers in those jurisdicons. 1 (4) To the extent this survey indicates no private right of acon exists, that merely indicates no private right of acon is expressly authorized by that jurisdicon’s general public accommodaon statute. -

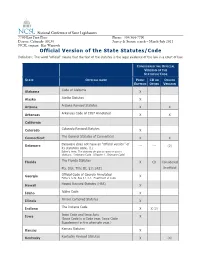

Official Version of the State Statutes/Code Definition: the Word "Official" Means That the Text of the Statutes Is the Legal Evidence of the Law in a Court of Law

National Conference of State Legislatures 7700 East First Place Phone: 303/364-7700 Denver, Colorado 80230 Survey & Statute search – March-July 2011 NCSL contact: Kae Warnock Official Version of the State Statutes/Code Definition: The word "official" means that the text of the statutes is the legal evidence of the law in a court of law. CONSIDERED THE OFFICIAL VERSION OF THE STATUTES/CODE STATE OFFICIAL NAME PRINT CD OR ONLINE EDITION OTHER VERSION Alabama Code of Alabama X Alaska Alaska Statutes X Arizona Arizona Revised Statutes X X Arkansas Arkansas Code of 1987 Annotated X X California Colorado Colorado Revised Statutes X Connecticut The General Statutes of Connecticut X X Delaware Delaware does not have an “official version” of --- --- (2) its statutory code. (1) Editor’s note: The statutes do give a name to use in citations. Delaware Code (Chapter 1. Delaware Code) Florida The Florida Statutes X CD Considered Fla. Stat. Title III, §11.2421 Unofficial Georgia Official Code of Georgia Annotated X Editor’s note: See § 1-1-1. Enactment of Code Hawaii Hawaii Revised Statutes (HRS) X Idaho Idaho Code X Illinois Illinois Compiled Statutes X Indiana The Indiana Code X X (3) Iowa Iowa Code and Iowa Acts X (Iowa Code in a Code year. Iowa Code Supplement in the alternate year.) Kansas Kansas Statutes X Kentucky Kentucky Revised Statutes X (4) CONSIDERED THE OFFICIAL VERSION OF THE STATUTES/CODE STATE OFFICIAL NAME PRINT CD OR ONLINE EDITION OTHER VERSION Louisiana West's Louisiana Statutes Annotated X Editor’s note: See RS 1:1 §1. -

Council of State Governments Capitol

THE COUNCIL OF STATE GOVERNMENTS SEPT 2011 CAPITOL RESEARCH SPECIAL REPORT Public Access to Official State Statutory Material Online Executive Summary As state leaders begin to realize and utilize the incredible potential of technology to promote trans- parency, encourage citizen participation and bring real-time information to their constituents, one area may have been overlooked. Every state provides public access to their statutory material online, but only seven states—Arkansas, Delaware, Maryland, Mississippi, New Mexico, Utah and Vermont—pro- vide access to official1 versions of their statutes online. This distinction may seem academic or even trivial, but it opens the door to a number of questions that go far beyond simply whether or not a resource has an official label. Has the information online been altered—in- tentionally or not—from its original form? Who is in March:2 “You’ve often heard it said that sunlight is responsible for mistakes? How often is it updated? the best disinfectant. And the recognition is that, for Is the information secure? If the placement of a re- us to do better, it’s critically important for the public source online is not officially mandated or approved to know what we’re doing.” by a statute or rule, its reliability and accuracy are At the most basic level, free and open public access difficult to gauge. to the law that governs this country—federal and As state leaders have moved quickly to provide state—is necessary to create the transparency that is information electronically to the public, they may fundamental to a functional participatory democracy. -

Research Memo

6/9/2009 Research Memo 09 RM 017 Date: June 4, 2009 Author: Kelley Shepp, Associate Research Analyst Re: Driving Under the Influence Laws and Penalties QUESTION 1. In Wyoming and other states, how many years after a driving under the influence (DUI) conviction does it take for subsequent DUI offenses to be tried as a first offense? 2. What is the criminal status of state DUI laws? 3. What substances do states list under their DUI statutes? 4. What are the sanctions for DUI accidents resulting in serious injury and/or death? ANSWER [Caveat: The information contained in the tables below has not been independently verified by LSO Research staff] 1. Table 1, below, depicts the time frames used for the inclusion of prior DUI offenses. 2. Table 2, below, outlines the criminal status of DUI laws. 3. Table 3, below, depicts the substances states list under their DUI statutes. 4. Although not all have, many states have implemented penalties specifically targeting DUI accidents involving serious injury or death. Table 4, below, depicts the sanctions states have implemented for DUI accidents resulting in serious injury or death. WYOMING LEGISLATIVE SERVICE OFFICE • 213 State Capitol • Cheyenne, Wyoming 82002 TELEPHONE (307) 777-7881 • FAX (307) 777-5466 • EMAIL • [email protected] • WEBSITE http://legisweb.state.wy.us PAGE 2 OF 20 Table 1. Time Frames Used for the Inclusion of Prior DUI Offenses. State Years Alabama 5 Years Alaska 10 Years Arizona 84 Months (7 Years) Arkansas 5 Years California 7 Years Colorado Lifetime Connecticut 10 Years Delaware 5 Years Florida 5 or 10 Years Georgia 5 Years Hawaii 5 Years Idaho 10 Years Illinois 5 Years Indiana 5 Years Iowa 12 Years Kansas All prior DUI convictions and DUI diversions count. -

Upper Limit on Current Support

Upper Limit on Current Support State Percentage If yes, how much Legal authority (statute or rule) for Comments limit on guidelines current support Yes No X Rule 32, Alabama Rules of Judicial Alabama Administration X Alaska Civil Rule 90.3 All awards are computed as % of gross Alaska w/ no ceiling % X Administrative Order No. 2004-29 Awards computed based on “combined Arizona adjusted gross” X 32% Arkansas Supreme Court Percentages are used when the income Arkansas Administrative Order number 10 level exceed the chart. 32% is the percentage for 6 children X California Family Code sections 4050- California 4076 X Colorado Statutes 14-10-115 “shared physical custody” results in Colorado multiplying the basic support obligation by 1.5 because of a resulting duplication in certain costs. X Connecticut General Statutes 46b- Connecticut 215a X 50% Delaware X D.C. Code Ann. 16-916.1 Guidelines effective 4/1/2007 District of Columbia X 55% Florida Statutes 61.30 Florida limitation is 55% of gross Florida income. X Georgia Code 19-6-15 Guidelines effective 1/1/2007 Georgia Page 1 of 6 August 2007 Upper Limit on Current Support State Percentage If yes, how much Legal authority (statute or rule) for Comments limit on guidelines current support Yes No X Primary support plus Hawaii Revised Statutes 576D-7 30% is for 3 or more children Hawaii 30% of SOLA SOLA income = gross income less self- income support reserve X 35% at $10,000 per Idaho Rules of Civil Procedure 6(c)6 35% is for 5 children at $10,000 annual Idaho year of guidelines income. -

New York University Law Library Golding Media Center List of Microform Holdings

New York University Law Library Golding Media Center List of Microform Holdings • 19th Century Legal Treatises • American Law Institute • Foreign Law • International Law • National Reporter System • New York State Law • Periodicals • State Session Laws • Superseded State Statutes • Theses • United States Federal Law & Governmental Documents • Misc. Revised January 10, 2017 Category Series Subseries Extent Form Case 19th Century Legal Treatises 19th Century Legal Treatises 1-85924 Fiche 90-92 American Law Institute American Law Institute (A.L.I.) ABACLE Review 1990-2006 Film 98 American Law Institute American Law Institute (A.L.I.) Committee on Continuing Prof. Education 1984-1986 Film 94 American Law Institute American Law Institute (A.L.I.) Proceedings 1946-1955 Film 94 American Law Institute American Law Institute (A.L.I.) ABACLE Review 1974-1989 Film 94 Foreign Law British and Foreign State Papers 1903-1968 Film 99 Foreign Law Canada Department of External Affairs 1928-1974 Fiche 76 Foreign Law Canada Exchequer Court 1891-1971 Fiche 76 Foreign Law Canada Federal Court 1972-1994 Fiche 76 Foreign Law Canada Gazette 1977-1980 Film 93 Foreign Law Central Court Session Papers (Old Bailey) 49 Reels Film 96 Foreign Law Court of Appeals Judgment 1951-1980 Fiche 76 Foreign Law Documents on British Policy Overseas 1984-1991 Fiche 85 Foreign Law English Law Reports 319 Reels Film 95 Foreign Law English Legal Manuscript Project Bodleian Library, Oxford Ms. Fiche 75 Foreign Law English Legal Manuscript Project Gray's Inn Library Ms. Fiche 75 Foreign Law English Legal Manuscript Project Harvard Law School Ms. Fiche 75 Foreign Law English Legal Manuscript Project Lincoln's Inn Library Ms. -

State Annexation Reporting Laws Date of Last Update: April 21, 2019

2021 STATE LAW SUMMARY TABLES AND STATEMENTS List of State Annexation Reporting Laws Date of Last Update: April 21, 2019. Definitions for State based tables below: Column 1 Type of legal action affecting incorporated place boundaries Column 2 Highest authorities to which incorporated place must file legal actions Column 3 Section(s) of the state law mandating the report Column 4 Name of the highest level of authority receiving the legal action Ctrl +Click on the state you need: Contents ALABAMA (01) ............................................................................................................................................... 3 ALASKA (02) Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) ........................................................................................ 4 ARIZONA (04) ................................................................................................................................................ 5 ARKANSAS (05) (MOA) .................................................................................................................................. 6 CALIFORNIA (06) ........................................................................................................................................... 7 COLORADO (08) ............................................................................................................................................ 8 CONNECTICUT (09)....................................................................................................................................... -

Llexisnexis Appendix B

LexisNexis Appendix B The image cannot be displayed. Your computer may not have enough memory to open the image, or the image may have been corrupted. Restart your computer, and then open the file again. If the red x still appears, you may have to delete the image and then insert it again. Primary Law International Legal: Argentina-1 Victoria Unreported Judgments Newfoundland & Labrador Cases from Publisher: Albrematica S.A. Publications International Legal: Canada-41 1971 (Vol 1) (Argentina Legislation) Canadian Legal Information Nova Scotia Cases from 1969 (Vol 1) International Legal: Australia-26 Alberta Cases from 1976 (Vol 1) Ontario Cases from 1984 (Vol 1) Australian General Case Law Alberta Regulations TOC Ontario Reports from 1931 ACT courts Unreported Judgments British Columbia Cases from 1991 (Vol 1) Prince Edward Island Cases from 1971 Australian & New Zealand Journal of Canada Federal Court Cases from 1986 (Vol 1 Criminology (Vol 1) Recueil des arrets de la Cour federale du Australian Administrative Law Reports Canada Federal Court Reports Canada de 1971 Australian Bar Review Canada Regulations Table of Contents Regulations of Canada Consolidated Australian Capital Territory Reports Canada Supreme Court Reports from 1876 Regulations of Ontario Australian Company Law Reports Causes du Quebec 1987-1995 (Vols 1-68) Regulations of Ontario Table of Contents Australian Competition and Consumer Law Consolidated Regulations of Alberta Regulations of Quebec Journal Consolidated Regulations of British Revised Statutes of Quebec Australian Corporations & Securities Columbia Saskatchewan Cases from 1980 (Vol 1) Reports Consolidated Regulations of British Supreme Court of Canada Cases from Australian Family Law Reports Columbia TOC Jan.