Citation Guest Editorial Journal of Language And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yachts Yachting Magazine NACRA F18 Infusion Test.Pdf

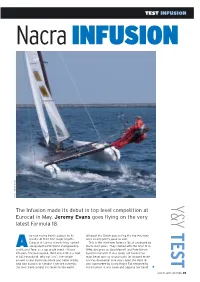

TEST INFUSION Nacra INFUSION S N A V E Y M E R E J O T O H P Y The Infusion made its debut in top level competition at & Eurocat in May. Jeremy Evans goes flying on the very latest Formula 18. Y T ny new racing boat is judged by its although the Dutch guys racing the top Infusions results. At their first major regatta — were clearly pretty good as well. Eurocat in Carnac in early May, ranked This is the third new Formula 18 cat produced by E A alongside the F18 World championship Nacra in 10 years. They started with the Inter 18 in and Round Texel as a top grade event — Nacra 1996, designed by Gino Morrelli and Pete Melvin S Infusions finished second, third and sixth in a fleet based in the USA. It was quick, but having the of 142 Formula 18. Why not first? The simple main beam and rig so unusually far forward made answer is that Darren Bundock and Glenn Ashby, it tricky downwind. Five years later, the Inter 18 T who won Eurocat in a Hobie Tiger are currently was superseded by a new Nacra F18 designed by the most hard-to-beat cat racers in the world, Alain Comyn. It was quick and popular, but could L YACHTS AND YACHTING 35 S N A V E Y M E R E J S O T O H P Above The Infusion’s ‘gybing’ daggerboards have a thicker trailing edge at the top, allowing them to twist in their cases and provide extra lift upwind. -

Société Des Régates De Douarnenez, Europe Championship Application

Société des Régates de Douarnenez, Europe championship Application Douarnenez, an ancient fishing harbor in Brittany, a prime destination for water sports lovers , the land of the island, “Douar An Enez” in Breton language The city with three harbors. Enjoy the unique atmosphere of its busy quays, wander about its narrows streets lined with ancient fishermen’s houses and artists workshops. Succumb to the charm of the Plomarch walk, the site of an ancient Roman settlement, visit the Museum Harbor, explore the Tristan island that gave the city its name and centuries ago was the lair of the infamous bandit Fontenelle, go for a swim at the Plage des Dames, “the ladies’ beach”, a stone throw from the city center. The Iroise marine park, a protected marine environment The Iroise marine park is the first designated protected marine park in France. It covers an area of 3500 km2, between the Islands of Sein and Ushant (Ouessant), and the national maritime boundary. Wildlife from seals and whales to rare seabirds can be observed in the park. The Société des Régates de Douarnenez, 136 years of passion for sail. The Société des Régates de Douarnenez was founded in 1883, and from the start competitive sailing has been a major focus for the club. Over many years it has built a strong expertise in the organization of major national and international events across all sailing series. sr douarnenez, a club with five dynamic poles. dragon dinghy sailing kiteboard windsurf classic yachting Discovering, sailing, racing Laser and Optimist one Practicing and promoting Sailing and promoting the Preserving and sailing the Dragon. -

Listado De Rating Abril 2014

Listado de Rating Abril 2014 CLASE Rating 2Win Sonic 1,283 2Win Sonic Solo 1,258 2Win Twincat 15 Sport 1,228 2Win Tyka 1,376 A Class Orzas Curvas 1,004 A Class Orzas Rectas 1,036 AHPC C2 F18 1,000 AHPC Capricorn F18 1,000 AHPC Taipan 4.9 1,023 AHPC Viper 1,035 AHPC Viper Solo 1,058 Alado 18 Aileron 1,091 Alado 18 F18 1,000 Bim 16 1,155 Bim 18 Class A (>100 Kgs) 1,090 Bim 18 Double 1,071 Bim 18 Double 96 CB 1,030 Bim 18 Double Sloop 1,047 Bim 20 1,030 Bimare Class A V1 1,037 Bimare X16 Double Spinnaker 1,115 Bimare X16 Solo 1,095 Bimare X16 Solo Spinnaker 1,049 Bimare X4 F18 1,000 Bimare X16F Plus 1,022 C 4.8 1,286 C 4.8 Major 1,255 Catapult 1,267 Cirrus B1 1,000 Cirrus Ecole 1,092 Cirrus Energy Regate 1,112 Cirrus Energy Regate Solo 1,141 Cirrus Evolution 1,039 Cirrus Evolution Solo 1,084 Cirrus F18 1,000 Condor 16 1,182 Dart 16 1,287 Dart 16 X Race 1,233 Dart 18 1,217 Dart 18 Cat Boat 1,264 Dart 18 Spinnaker 1,178 Dart 20 1,109 Dart 6000 1,136 Dart Hawk F18 1,000 Dart Sting 1,355 Dart Sting Cat Boat 1,365 Dart Sting Solo 1,259 Dart TSX 1,057 Diam 3 F18 1,000 Drake 1,024 Falcon F16 1,028 Falcon F16 Cat Boat 1,052 Formula 20 White Formula 0,956 Formule 18 1,000 Formule 20 0,961 Gwynt 14 1,254 Hawke Surfcat 7020 1,321 Hawke Surfcat 7020 (Main Only) 1,471 Hobie 13 1,590 Hobie 14 LE 1,383 Hobie 14 Turbo 1,256 Hobie 15 1,305 Hobie 16 LE (without spinnaker) 1,184 Hobie 16 Spinnaker (Europe) 1,133 Hobie 17 (with wings) 1,212 Hobie 18 1,098 Hobie 18 Formula 1,039 Hobie 18 Formula 104 1,072 Hobie 18 Magnum 1,098 Hobie 18 SX 1,122 Hobie 20 Formula -

Deutsche Meisterschaften Und Platzierte 2009

Deutsche Meisterschaften und Platzierte 2009 Bootsklasse Platz Mannschaft Verein DSV-Nr. IDM 15 qm 1. Wilfried Schweer / Bernd Koy STSV N048 03.08.-07.08. 15 qm 2. Michael Hotho / Hugo Dölfes SCP BA077 15 qm 3. Jan Hustert / Morten Häger SCD N061 15 qm 4. Andreas Zethner / Erich Zethner Österreich 15 qm 5. Thomas Budde / Uwe Bertallot SVH N062 15 qm 6. Robert Heymann / Thomas Schüler MSVB BG020 DM 20 qm 1. Thomas Flach / Sven Diedering / Harald Schaale BTB B121 06.09.-11.09 20 qm 2. Christian Friedrich / Friedrich Göing / Matthias Schönfelder SVUH B030 20 qm 3. Florian Stock / Stefan Seifert / Tobias Barthel ARV08 SA034 20 qm 4. Lucas Zellmer / Michael Wiedstruck / Bernd Muschke SPYC B023 20 qm 5. Jörg Witte / Stepha Mädicke / Martin Herbst TSG B100 20 qm 6. Kay-Uwe Lüdtke / Karsten Schulz / Carsten Sumpf YCBG B120 DM 29er 1. Philipp Müller / Moritz Janich HSC BA016 09.10.-11.10. 29er 2. Simon Winter / Kilian Holzapfel SRV BA075 29er 3. Karin Marchart / Tina Marchart YCaT BA036 29er 4. Justus Schmidt / Max Böhme KYC SH017 29er 5. Jule Görge / Lotta Görge KYC SH017 29er 6. Stefan Gieser / Felix Meggendorfer WHW BW078 IDM 49er keine DM 11.06.-14.06. IDM 420er 1. Julian Autenrieth / Philipp Autenrieth BYC BA001 09.10.-13.10. 420er 2. Frederike Loewe / Anna Rattemeyer SVR B116 420er 3. Till Krüger / Oliver Wichert MSC HA033 420er 4. Jan Schliemann / Aaron Scherr YCRA BW003 420er 5. Malte Winkel / Lucas Thielemann SYC MV004 420er 6. Gordon Nickel / Daniel-Philip Hoffmann SVC N005 IDM 470er 1. Lucas Zellmer / Heiko Seelig SPYC B023 29.09.-04.10. -

The International Flying Dutchman Class Book

THE INTERNATIONAL FLYING DUTCHMAN CLASS BOOK www.sailfd.org 1 2 Preface and acknowledgements for the “FLYING DUTCHMAN CLASS BOOK” by Alberto Barenghi, IFDCO President The Class Book is a basic and elegant instrument to show and testify the FD history, the Class life and all the people who have contributed to the development and the promotion of the “ultimate sailing dinghy”. Its contents show the development, charm and beauty of FD sailing; with a review of events, trophies, results and the role past champions . Included are the IFDCO Foundation Rules and its byelaws which describe how the structure of the Class operate . Moreover, 2002 was the 50th Anniversary of the FD birth: 50 years of technical deve- lopment, success and fame all over the world and of Class life is a particular event. This new edition of the Class Book is a good chance to celebrate the jubilee, to represent the FD evolution and the future prospects in the third millennium. The Class Book intends to charm and induce us to know and to be involved in the Class life. Please, let me assent to remember and to express my admiration for Conrad Gulcher: if we sail, love FD and enjoyed for more than 50 years, it is because Conrad conceived such a wonderful dinghy and realized his dream, launching FD in 1952. Conrad, looked to the future with an excellent far-sightedness, conceived a “high-perfor- mance dinghy”, which still represents a model of technologic development, fashionable 3 water-line, low minimum hull weight and performance . Conrad ‘s approach to a continuing development of FD, with regard to materials, fitting and rigging evolution, was basic for the FD success. -

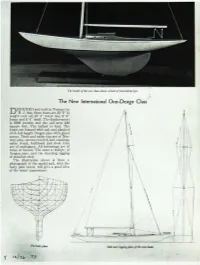

The New International One-Design Class ESIGNED and Built in Norway by D B

T he model of the new c~s shoii'S a bocu of interestin!I IYP" The New International One-Design Class ESIGNED and built in Norway by D B. J. Aas, these boats are 33' 2" in length over all, 21' 5" water line, 6' 9" beam and 5' 4" draft. The displacement is 6800 pounds and the sail area 426 11 I square feet. The ballast is lead. The ~ boats are framed with oak and planked \ with full length Oregon pine with glued \ seams. Deck and cabin top are of Nor I. way pine, canvas covered, and coaming, cabin trunk, bulkhead and deck trim are of mahogany. All fastenings are of brass or bronze. The mast is hollow, of Oregon pine, and the standing rigging of stainless steel. The ill ustration above is from a I photograph of the model and, wi th the I body plan below, wi ll give a good idea of the boats' appearance. ~ / The "R" bodts once mdde up " scrdppy Sound rdcing cldss. Most of them hdve now migrdted to the Gredt Ldkes ISLAND SOUND RACING- W·HAT NEXT? By WILLIAM H. TAYLOR HAT'S happening to yacht racing on as the financial and business collapse that made it inevitable, Long Island Sound? The question has but it has been steady and inexorable throughout~the past been asked a good many times in the last decade. What \vith war and taxes, it certainly hasn't hit two or three years and answered in a good bottom yet. many ways, by Jeremiahs, Pollyannas, So where are we now? Internationals, Victories, 11 S" and by persons of various shades of opinion boats, Interclubs .and Atlantics were the 11 big" classes of --· -~~ two extremes. -

Formula 18 Class

Formula 18 Class Proposal to Host 2012 World Championship ALAMITOS BAY YACHT CLUB HTTP://WWW.ABYC.ORG FORMULA 18 CLASS INTRODUCTION • 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.................................................................................................................................................5 Proposal .......................................................................................................................................................6 Experience...................................................................................................................................................7 Overview..................................................................................................................................................................7 Previous Major Regattas.......................................................................................................................................7 Olympic Regattas ...................................................................................................................................................................7 World Championships ...........................................................................................................................................................7 North American, National and Regional Championships....................................................................................................8 Awards ....................................................................................................................................................................................9 -

The First Fifty Years People, Memories and Reminiscences Contents

McCrae Yacht Club – the First Fifty Years People, Memories and Reminiscences Contents Championships Hosted at McCrae ...................................................................................................2 Our champion sailors...........................................................................................................................5 Classes Sailed over the years.......................................................................................................... 12 Stories from various sailing events.............................................................................................. 25 Rescues and Tall Tales...................................................................................................................... 31 Notable personalities........................................................................................................................ 37 Did you know? – some interesting trivia.................................................................................... 43 Personal Recollections and Reminiscences .............................................................................. 46 The Little America’s Cup – what really happened ….. ............................................................ 53 McCrae Yacht Club History - firsts ................................................................................................ 58 Championships Hosted at McCrae The Club started running championships in the second year of operation. The first championships held in 1963/64 -

A Pictorial History of the Star Class

FOREWORD From its very beginning the Star Class has attracted photographers’ attention. Morris Rosenfeld and Edwin Levick were among the early photographers who took pictures of the Star. The beauty and power of the modern Star boat continues to be an object interest for both amateur and professional photographer. We are thus fortunate to have a fairly good pictorial record of the Star Class starting with those early days of 1911 when the Stars first put in an appearance on Long Island Sound and at Nahant Dory Club in Massachusetts. The Star Class also has a very good historical record of itself. An annual Log which lists the boats and their owners, gives race results, carries the Class Rules, and other pertinent information has been published since 1922. An additional source of information is available from Starlights, the Star Class newsletter which has been published since 1925. Added to these sources there are two history books about the Star Class: “Forty Years Among the Star”, written by George W. Elder, and “A History of the Star Class”, written by Class Historian and long-time Log and Starlights editor C. Stanley Ogilvy. It is the purpose of this pictorial history to bring together some of the more interesting photographs and events which have appeared in the Star Class publications. PRELUDE The Gaff Rigged Era 1911 – 1920 (and before) The history of the Star began even before 1911. In 1906 a boat called the Bug was designed in the office of William Gardner in New York. These boats about eighteen feet long, were miniature Stars, their design being very similar to the as yet unborn Star boat. -

LIVING Innovation for and by the People

FACTS & FIGURES 2015 LIVING Innovation for and by the people inspiring a better way of living accessible to all Facts & Figures 2015 1. PROFILE Inspiring a better way of living accessible to all 3 SOMFY Everyone around the world aspires to a safe, healthy and environmentally- friendly living environment. To meet this essential need of improving living environments, the Somfy group creates innovative solutions for homes and buildings, in three key areas: – the security of people and property, – energy saving and protecting the environment, – wellbeing for everyone at all ages. Somfy group, through each of its sub- sidiaries and brands, is committed to making these innovations accessible to all. Present in 58 countries and across five continents, Somfy adapts its solu- tions to the needs and characteristics of each of its markets. 3 1. Profile Facts & Figures 2015 5 SOMFY Our project is part of our vocation and composed of two elements: one dedicated to business, Better Living For All, the other to the managerial and human aspects, Better Living Together. Better Living For All In a market undergoing rapid change with the development of digital and connectivity, it is essential to anticipate to seize opportunities. Somfy is driving its development by focusing on its five key assets: – Innovation, giving the market the best Better Living Together connected motors. – Powerful brands. To overcome future challenges, Somfy – High-quality and interconnecting group needs to function in a simpler, distribution channels, with a unique more fluid and more agile way. United network of installers who work closely around its values, with employees with customers; the development of who work effectively together: open, new channels, particularly digital, to inspired and collaborative. -

Listado De Rating Junio 2013

Listado de Rating Junio 2013 CLASE Rating 2Win Sonic 1,279 2Win Sonic Solo 1,241 2Win Twincat 15 Sport 1,224 2Win Tyka 1,374 A Class Orzas Curvas 0,99 A Class Orzas Rectas 1,006 AHPC C2 F18 0,988 AHPC Capricorn F18 0,988 AHPC Taipan 4.9 1,008 AHPC Viper 1,022 AHPC Viper Solo 1,037 Alado 18 Aileron 1,087 Alado 18 F18 0,988 Bim 16 1,15 Bim 18 Class A (>100 Kgs) 1,063 Bim 18 Double 1,054 Bim 18 Double 96 CB 1,01 Bim 18 Double Sloop 1,045 Bim 20 1,014 Bimare Class A V1 1,007 Bimare X16 Double Spinnaker 1,102 Bimare X16 Solo 1,064 Bimare X16 Solo Spinnaker 1,027 Bimare X4 F18 0,988 Bimare X16F Plus 1,01 C 4.8 1,297 C 4.8 Major 1,25 Catapult 1,258 Cirrus B1 0,988 Cirrus Ecole 1,097 Cirrus Energy Regate 1,114 Cirrus Energy Regate Solo 1,125 Cirrus Evolution 1,031 Cirrus Evolution Solo 1,065 Cirrus F18 0,988 Condor 16 1,186 Dart 16 1,289 Dart 16 X Race 1,235 Dart 18 1,221 Dart 18 Cat Boat 1,253 Dart 18 Spinnaker 1,182 Dart 20 1,1 Dart 6000 1,12 Dart Hawk F18 0,988 Dart Sting 1,369 Dart Sting Cat Boat 1,354 Dart Sting Solo 1,247 Dart TSX 1,047 Diam 3 F18 0,988 Drake 1,023 Falcon F16 1,015 Falcon F16 Cat Boat 1,032 Formula 20 White Formula 0,946 Formule 18 0,988 Formule 20 0,945 Gwynt 14 1,265 Hawke Surfcat 7020 1,303 Hawke Surfcat 7020 (Main Only) 1,454 Hobie 13 1,6 Hobie 14 LE 1,395 Hobie 14 Turbo 1,259 Hobie 15 1,315 Hobie 16 LE (without spinnaker) 1,195 Hobie 16 Spinnaker (Europe) 1,143 Hobie 17 (with wings) 1,199 Hobie 18 1,096 Hobie 18 Formula 1,032 Hobie 18 Formula 104 1,068 Hobie 18 Magnum 1,096 Hobie 18 SX 1,122 Hobie 20 Formula 1,022 -

Spinnaker Fabrics? Characteristics, High Stability , Low Weight, Zero Porosity and Water Repellency

America’sAmerica’s CupCup TheThe lastlast threethree America’sAmerica’s CupCup winnerswinners allall selectedselected ContenderContender SpinnakerSpinnaker Formed in The Netherlands in 1986, Contender Sailcloth is a worldwide organization devoted to supplying sailmakers with the best available fabrics for cloth for their downwind sails cloth for their downwind sails all their sailmaking requirements. Sailcloth and the related hardware for the manufacture of sails forms the principal business. The of fices are run by sailors who actively par ticipate in the spor t at all levels, from One-design to Grand Prix to Cruising. Contender understands the needs of sailmakers and works with them to provide the best materials for the job. Contender enjoys strong working relationships with yarn suppliers, weavers, and 19951995 SanSan DiegoDiego finishers in Europe and Nor th America. W ith the unique understanding of the Team NZ defeats Young America 5-0 Team NZ defeats Young America 5-0 sailcloth market, Contender uses the resources of these par tners to meet the demands of the market with innovative fabrics using the latest in fibre, weaving 20002000 AucklandAuckland and finishing technologies. TeamTeam NZNZ defeatsdefeats PradaPrada 5-05-0 The result is a range of fabrics renowned for its quality and per formance. 20032003 AucklandAuckland AlinghiAlinghi defeatsdefeats TeamTeam NZNZ 5-05-0 Contender Worldwide Headoffice: Contender The Netherlands Contender U.S. • Contender Australia • Contender U.K. • Contender France Contender Italy • Contender