A Comparative Study of Religions J.N.K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

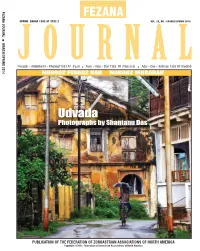

Summer/June 2014

AMORDAD – SHEHREVER- MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. 28, No 2 SUMMER/JUNE 2014 ● SUMMER/JUNE 2014 Tir–Amordad–ShehreverJOUR 1383 AY (Fasli) • Behman–Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin 1384 (Shenshai) •N Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin–ArdibeheshtAL 1384 AY (Kadimi) Zoroastrians of Central Asia PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Copyright ©2014 Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America • • With 'Best Compfiments from rrhe Incorporated fJTustees of the Zoroastrian Charity :Funds of :J{ongl(pnffi Canton & Macao • • PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 28 No 2 June / Summer 2014, Tabestan 1383 AY 3752 Z 92 Zoroastrianism and 90 The Death of Iranian Religions in Yazdegerd III at Merv Ancient Armenia 15 Was Central Asia the Ancient Home of 74 Letters from Sogdian the Aryan Nation & Zoroastrians at the Zoroastrian Religion ? Eastern Crosssroads 02 Editorials 42 Some Reflections on Furniture Of Sogdians And Zoroastrianism in Sogdiana Other Central Asians In 11 FEZANA AGM 2014 - Seattle and Bactria China 13 Zoroastrians of Central 49 Understanding Central 78 Kazakhstan Interfaith Asia Genesis of This Issue Asian Zoroastrianism Activities: Zoroastrian Through Sogdian Art Forms 22 Evidence from Archeology Participation and Art 55 Iranian Themes in the 80 Balkh: The Holy Land Afrasyab Paintings in the 31 Parthian Zoroastrians at Hall of Ambassadors 87 Is There A Zoroastrian Nisa Revival In Present Day 61 The Zoroastrain Bone Tajikistan? 34 "Zoroastrian Traces" In Boxes of Chorasmia and Two Ancient Sites In Sogdiana 98 Treasures of the Silk Road Bactria And Sogdiana: Takhti Sangin And Sarazm 66 Zoroastrian Funerary 102 Personal Profile Beliefs And Practices As Shown On The Tomb 104 Books and Arts Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org AMORDAD SHEHREVER MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. -

Rostam As a Pre-Historic Iranian Hero Or the Shi'itic Missionary?

When Literature and Religion Intertwine: Rostam as a Pre-Historic Iranian Hero or the Shi’itic Missionary? Farzad Ghaemi Department of Persian Language and Literature, Faculty of Letters and Humanities, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Azadi Square, Mashhad, Khorasan Province 9177948883, Iran Email: [email protected] Azra Ghandeharion* (Corresponding Author) Department of English Studies, Faculty of Letters and Humanities, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Azadi Square, Mashhad, Khorasan Province 9177948883, Iran Email: [email protected] Abstract This article aims to show how Rostam, the legendary hero of Iranian mythology, have witnessed ideological alterations in the formation of Persian epic, Shahnameh. Among different oral and written Shahnamehs, this paper focuses on Asadi Shahnameh written during the 14th or 15th century. Though he is a pre- Islamic hero, Rostam and his tasks are changed to fit the ideological purposes of the poet’s time and place. A century later, under the influence of the state religion of Safavid Dynasty (1501–1736), Iranian pre-Islamic values underwent the process of Shi’itization. Scarcity of literature regarding the interpretation of Asadi Shahnameh and the unique position of this text in the realm of Persian epic are the reasons for our choice of scrutiny. In Asadi Shahnameh Rostam is both a national hero and a Shi’ite missionary. By meticulous textual and historical analysis, this article shows how Asadi unites seemingly rival subjects like Islam with Zoroastrianism, philosophy with religion, and heroism with mysticism. It is concluded that Asadi’s Rostam is the Shi’ite-Mystic version of Iranians’ popular hero who helps the cause of Shi’itic messianism and performs missionary tasks in both philosophic and practical levels. -

The Second After the King and Achaemenid Bactria on Classical Sources

The Second after the King and Achaemenid Bactria on Classical Sources MANEL GARCÍA SÁNCHEZ Universidad de Barcelona–CEIPAC* ABSTRACT The government of the Achaemenid Satrapy of Bactria is frequently associated in Classical sources with the Second after the King. Although this relationship did not happen in all the cases of succession to the Achaemenid throne, there is no doubt that the Bactrian government considered it valuable and important both for the stability of the Empire and as a reward for the loser in the succession struggle to the Achaemenid throne. KEYWORDS Achaemenid succession – Achaemenid Bactria – Achaemenid Kingship Crown Princes – porphyrogenesis Beyond the tradition that made of Zoroaster the and harem royal intrigues among the successors King of the Bactrians, Rege Bactrianorum, qui to the throne in the Achaemenid Empire primus dicitur artes magicas invenisse (Justinus (Shahbazi 1993; García Sánchez 2005; 2009, 1.1.9), Classical sources sometimes relate the 155–175). It is in this context where we might Satrapy of Bactria –the Persian Satrapy included find some explicit references to the reward for Sogdiana as well (Briant 1984, 71; Briant 1996, the prince who lost the succession dispute: the 403 s.)– along with the princes of the offer of the government of Bactria as a Achaemenid royal family and especially with compensation for the damage done after not the ruled out prince in the succession, the having been chosen as a successor of the Great second in line to the throne, sometimes King (Sancisi–Weerdenburg 1980, 122–139; appointed in the sources as “the second after the Briant 1984, 69–80). -

Persian-Thessalian Relations in the Late Fifth Century BC

The Prince and the Pancratiast: Persian-Thessalian Relations in the Late Fifth Century B.C. John O. Hyland EAR THE END of the fifth century B.C. the famous Thes- salian pancratiast Poulydamas of Skotoussa traveled to Nthe Achaemenid court at the invitation of Darius II. Scholars have noted the visit as an instance of cultural inter- action, but Persia’s simultaneous involvement in the Pelopon- nesian War suggests the possibility of diplomatic overtones. A political purpose for Poulydamas’ travel would be especially at- tractive given the subsequent cooperation between Darius’ son, Cyrus the Younger, and a cabal of Thessalian guest-friends. These episodes may be linked as successive steps in the restora- tion of the old xenia between Xerxes and Thessalian leaders, dormant since 479. By examining what Persian and Thessalian elites stood to gain from renewing their old partnership, we can shed new light on an under-appreciated dimension of Graeco- Persian political relations. The pancratiast’s visit: Poulydamas, Darius II, and Cyrus Poulydamas’ victory at the Olympic games of 408 made him a living legend in Greece, a strongman comparable to Herakles (Paus. 6.5.1–9).1 Plato’s Republic testifies to his fame outside of Thessaly in the first half of the fourth century, citing him as the 1 For the date see Luigi Moretti, Olympionikai: i vincitori negli antichi agoni Olympici (Rome 1957), no. 348. For Poulydamas’ emulation of Herakles, and similar associations for Milo and other Olympic victors see David Lunt, “The Heroic Athlete in Ancient Greece,” Journal of Sport History 36 (2009) 380–383. -

Zoroastrians Their Religious Beliefs and Practices

Library of Religious Beliefs and Practices General Editor: John R. Hinnells The University, Manchester In the series: The Sikhs W. Owen Cole and Piara Singh Sambhi Zoroastrians Their Religious Beliefs and Practices MaryBoyce ROUTLEDGE & KEGAN PAUL London, Boston and Henley HARVARD UNIVERSITY, UBRARY.: DEe 1 81979 First published in 1979 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd 39 Store Street, London WC1E 7DD, Broadway House, Newtown Road, Henley-on-Thames, Oxon RG9 1EN and 9 Park Street, Boston, Mass. 02108, USA Set in 10 on 12pt Garamond and printed in Great Britain by Lowe & BrydonePrinters Ltd Thetford, Norfolk © Mary Boyce 1979 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in criticism British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Boyce, Mary Zoroastrians. - (Libraryof religious beliefs and practices). I. Zoroastrianism - History I. Title II. Series ISBN 0 7100 0121 5 Dedicated in gratitude to the memory of HECTOR MUNRO CHADWICK Elrington and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon in the University of Cambridge 1912-4 1 Contents Preface XJ1l Glossary xv Signs and abbreviations XIX \/ I The background I Introduction I The Indo-Iranians 2 The old religion 3 cult The J The gods 6 the 12 Death and hereafter Conclusion 16 2 Zoroaster and his teaching 17 Introduction 17 Zoroaster and his mission 18 Ahura Mazda and his Adversary 19 The heptad and the seven creations 21 .. vu Contents Creation and the Three Times 25 Death and the hereafter 27 3 The establishing of Mazda -

Cannabis in the Ancient World Chris Bennet

Cannabis in the Ancient World Chris Bennet The role of cannabis in the ancient world was manifold, a food, fiber, medicine and as a magically empowered religious sacrament. In this paper the focus will be on archaic references to cannabis use as both a medicine and a sacrament, rather than as a source of food or fiber, and it’s role in a variety of Ancient cultures in this context will be examined. Unfortunately, due to the deterioration of plant matter archeological evidence is sparse and “Pollen records are frequently unreliable, due to the difficulty in distinguishing between hemp and hop pollen” (Scott, Alekseev, Zaitseva, 2004). Despite these difficulties in identification some remains of cannabis fiber, cannabis beverages utensils, seeds of cannabis and burnt cannabis have been located (burnt cannabis has been carbonized and this preserves identifiable fragments of the species). Fortunately other avenues of research regarding the ancient use of cannabis remain open, and etymological evidence regarding cannabis use in a number of cultures has been widely recognized and accepted. After nearly a lifetime of research into the role of psychoactive plants in human history the late Harvard University Professor of ethnobotany, Richard Evans Schultes commented: "Early man experimented with all plant materials that he could chew and could not have avoided discovering the properties of cannabis (marijuana), for in his quest for seeds and oil, he certainly ate the sticky tops of the plant. Upon eating hemp, the euphoric, ecstatic and hallucinatory aspects may have introduced man to the other-worldly plane from which emerged religious beliefs, perhaps even the concept of deity. -

Vakhshuraan Zarathushtra Spitamaan's First Gatha Ahunavaiti - Yasna 34, Verses 1-2 Hello All Tele Class Friends

Weekly Zoroastrian Scripture Extract # 373: Vakhshur-e- Vakhshuraan Zarathushtra Spitamaan's First Gatha Ahunavaiti - Yasna 34, Verses 1-2 Hello all Tele Class friends: Maidhyoshahem Gaahambaar and Tirangaan and Aarish the Iranian Archer: According to the Seasonal calendar, Maidhyoshahem Gaahambaar started on Tir Maah and Khorshed Roj (29th June) and ends on today Tir Maah and Dae-pa-Meher Roj (July 3rd). Also, in between this Gaahambaar, on Tir Maah and Tir Roj, the Parabh (auspicious day) of Tirangaan also took place on July 1st. According to our Gaahambaar Aafrin, Maidhyoshahem Gaahambaar is the second Gaahambaar and Daadaar Ahura Mazda created water during this Gaahambaar. Many of our Zoroastrian Associations do celebrate this Gaahambaar in their Atashkadehs which is quite commendable, especially if it is on Tirangaan. In Iran, Tirangaan was celebrated with lots of fanfare. It celebrated the Tir Parabh (auspicious day) plus the famous story of the brave Iranian Archer Arish who gave his life by shooting an arrow with all his might which determined the boundary of Iran and its enemy Turan. That was when Iranian king Minocheher and Turanian King Afraasiyaab agreed to stop the war and determine the boundary by having an Iranian archer shoot an arrow and where the arrow came down, it determined the boundary between the two kingdoms and Iran got the better part of the deal. Of course, Archer Arish was chosen, and he gave all his strength to shoot the arrow from the top of the highest Iranian Damaavand Mountain, but after that he died due to the extreme physical effort. -

General Introduction

PERSIAN TRADITIONS IN SPAIN by Michael McClain (1) PREFACE First let me introduce myself. People who know me very well say that I have a mentality which is medieval and not modern, rural and not urban, that I am an “incurable romantic and idealist”, and that I have a “peasant mindset”. To all of the above I plead guilty, and as the Spanish say, y a mucha honra, in other words, I am proud of it. When one speaks of relations between Spain and Persia or of Persian influences in Spain, most people immediately think of elements which entered the Iberian Penninsula during the long period of Muslim dominance. This theme has been subject of many studies, by Hussein Munis and E. Levi-Provençal among others. For the above reasons, in the present study I am devoting much space to relations or influences which either predate the Muslim Conquest of Spain, which entered independently of said conquest, or, though they may have first entered with the Crescent of Islam, remained long after said Crescent had waned and set. To do a really complete and thorough study of this topic would require a great deal more time and money than I at present have at my disposal. In particular, it would require a long journey through Portugal, Aragon, Catalunya and Valencia, not to mention Iran. I have chosen to devote much time to Toledo, which was capital of Spain in Visigothic times and which is really a synthesis of all cultures, religions and artistic styles which form the threads of the multicolored fabric, part Celtic tartan, part Oriental carpet, (2) which is the history of Spain. -

Spring 2014-Ver04.Indd

ZOROASTRIAN SPORTS COMMITTEE With Best Compliments is pleased to announce from ththth The Incorporated Trustees The 14 Z Games of the July 2-6, 2014 Zoroastrian Charity Funds of Cal State Dominguez Hills Los Angeles, CA, USA Hongkong, Canton & Macao ONLINE REGISTRATION NOW OPEN! www.ZATHLETICS.com www.zathletics.com | [email protected] FOR UP TO THE MINUTE DETAILS, FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA @ZSports @ZSports ZSC FEZANA JOURNAL PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 28 No 1 March / Spring 2014, Bahar 1383 AY 3752 Z 2224 36 60 02 Editorials 83 Behind the Scenes 122 Matrimonials 07 FEZANA Updates Firoza Punthakey-Mistree and 123 Obituary Pheroza Godrej 13 FEZANA Scholarships 126 Between the Covers Maneck Davar 41 Congress Follow UP FEZANA JOURNAL Ashishwang Irani Darius J Khambata welcomes related stories 95 In the News from all over the world. Be Khojeste Mistree a volunteer correspondent 105 Culture and History Dastur Peshotan Mirza or reporter 114 Interfaith & Interalia Dastur Khurshed Dastoor CONTACT 118 Personal Profile Issues of Fertility editor(@)fezana.org 119 Milestones Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, lmalphonse(@)gmail.com Language Editor: Douglas Lange Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, ffitch(@)lexicongraphics.com Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia bpastakia(@)aol.com Cover design Columnists: Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi: rabadis(@)gmail.com; Feroza Fitch -

Zoroaster : the Prophet of Ancient Iran

BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF 1891 AJUUh : :::^.l.ipq.'f.. "Jniversity Library DL131 1o5b.J13Hcirir'^PItl®" ^°'°nnmliA ,SI'.?.P!}SL°LmmX Jran / 3 1924 022 982 502 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924022982502 ZOROASTER THE PROPHET OF ANCIENT IRAN •The; •S- ZOROASTER THE PROPHET OF ANCIENT HIAN BY A. V. WILLIAMS JACKSON PROFESSOK OF INDO-IBANIAN LANGUAGES IN COLUMBIA UNIVKRSITT KTefa gorft PUBLISHED FOE THE COLUMBIA UNIVEESITT PRESS BY THE MACMILLAN COMPANY LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., Ltd. 1899 All rights reserved Copyright, 1898, bt the macmillan company. J. S. Gushing k Co. — Berwick & Smith Norwood Mass. U.S.A. DR. E. W. WEST AS A MARK OF REGARD PREFACE This work deals with the life and legend of Zoroaster, the Prophet of Ancient Iran, the representative and type of the laws of the Medes and Persians, the Master whose teaching the Parsis to-day still faithfully follow. It is a biographical study based on tradition ; tradition is a phase of history, and it is the purpose of the volume to present the picture of Zoroaster as far as possible in its historic light. The suggestion which first inspired me to deal with this special theme came from my friend and teacher. Professor Geldner of Berlin, at the time when I was a student under him, ten years ago, at the University of Halle in Germany, and when he was lecturing for the term upon the life and teachings of Zoroaster. -

Vishtaspa Krny: an Achaemenid Military Official in 4Th-Century Bactria

Arta 2013.002 John Hyland – Christopher Newport University Vishtaspa krny: an Achaemenid military offi cial in 4th-century Bactria1 The publication of the Aramaic archive from fourth-century Bactria (ADAB: Naveh and Shaked 2012) sheds new light on the eastern satrapies in the last decades of the Achaemenids and the era of Alexander. Historians have long been frustrated by the paucity of written sources on the region, even in the narrow window off ered by classical accounts of Alexander’s campaigns, and the appearance of new evidence is cause for great excitement. The ADAB documents refer to numerous individuals unattested in other written sources, from minor village offi cials to a probable satrap of Bactria in the reign of Artaxerxes III. The infamous regicide and would-be king Bessus, previously known from classical authors alone, appears now in a Bactrian context, separated from his role in the fall of the Achaemenid dynasty (ADAB C1).2 Another individual who may appear in both the Alexander histories and the Bactrian archive is a certain Vishtaspa (wšt’sp), who appears in a short letter concerning a transfer of sheep between two other men with Iranian names (ADAB C2: 1).3 The editors note the existence of a prominent general named Hystaspes in the reigns of Darius III and Alexander, but do not press the identifi cation.4 His asso- 1 I am grateful to Pierre Briant and the editors of Arta for their valuable comments and critique on an initial version of this paper. I would also like to thank Eduard Rung and Marek Jan Olbrycht for graciously sharing their relevant scholarship with me.