1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Otorisama Continues to Be Loved by the People

2020 edition Edo to the Present The Sugamo Otori Shrine, located near the Nakasendo, has been providing a spiritual Ⅰ Otorisama continues to be loved sanctuary to the people as Oinarisama (Inari god) and continues to be worshipped and by the people loved to this today. Torinoichi, the legacy of flourishing Edo Stylish manners of Torinoichi The Torinoichi is famous for its Kaiun Kumade Mamori (rake-shaped amulet for Every November on the day of the good luck). This very popular good luck charm symbolizes prosperous business cock, the Torinoichi (Cock Fairs) are and is believed to rake in better luck with money. You may hear bells ringing from all held in Otori Shrines across the nation parts of the precinct. This signifies that the bid for the rake has settled. The prices and many worshippers gather at the of the rakes are not fixed so they need to be negotiated. The customer will give the Sugamo Otori Shrine. Kumade vendor a portion of the money saved from negotiation as gratuity so both The Sugamo Otori Shrine first held parties can pray for successful business. It is evident through their stylish way of business that the people of Edo lived in a society rich in spirit. its Torinoichi in 1864. Sugamo’s Torinoichi immediately gained good reputation in Edo and flourished year Kosodateinari / Sugamo Otori Shrine ( 4-25 Sengoku, Bunkyo Ward ) MAP 1 after year. Sugamo Otori Shrine was established in 1688 by a Sugamo resident, Shin However, in 1868, the new Meiji Usaemon, when he built it as Sugamoinari Shrine. -

Japanese Woodblock Prints at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston Hokusai Exhibit 2015 Tokugawa Ieyasu Tokugawa Clan Rules 1615- 1850

From the Streets to the Galleries: Japanese Woodblock Prints at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston Hokusai Exhibit 2015 Tokugawa Ieyasu Tokugawa Clan Rules 1615- 1850 Kabuki theater Utamaro: Moon at Shinagawa (detail), 1788–1790 Brothel City Fashions UTAGAWA KUNIYOSHI, TAKEOUT SUSHI SUGGESTING ATAKA, ABOUT 1844 A Young Man Dallying with a Courtesan about 1680 attributed to Hishikawa Moronobu Book of Prints – Pinnacle of traditional woodblock print making Driving Rain at Shono, Station 46, from the Fifty-three Stations of the Tokkaido Road, 1833, Ando Hiroshige Actor Kawarazaki Gonjuro I as Danshichi 1860, Artist: Kunisada The In Demand Type from the series Thirty Two Physiognomic Types in the Modern World Artist: Utagawa Kunisada 1820s The Mansion of the Plates, From the Series One Hundred Ghost Stories, about 1831, Artist Katsushika Hokusai Taira no Tadanori, from the Series Warriors as Six Poetic Immortals Artist Yashima Gakutei, About 1827, Surimono Meiji Restoration. Forecast for the Year 1890, 1883, Ogata Gekko Young Ladies Looking at Japanese objects, 1869 by James Tissot La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese costume) Claude Monet, 1876 The Fish, Stained glass Window, 1890, John La Farge Academics and Adventurers: Edward S. Morse, Okakura Kakuzo, Ernest Fenollosa, William Sturgis Bigelow New Age Japanese woman, About 1930s Edward Sylvester Morse Whaleback Shell Midden in Damariscotta, Maine Brachiopod Shell Brachiopod worm William Sturgis Bigelow Ernest Fenollosa Okakura Kakuzo Charles T. Spaulding https://www.mfa.org/collections /asia/tour/spaulding-collection Stepping Stones in the Afternoon, Hiratsuka Un’ichi, 1960 Azechi Umetaro, 1954 Reike Iwami, Morning Waves. 1978 Museum of Fine Arts Toulouse Lautrec and the Stars of Paris April 7-August 4 Uniqlo t-shirt. -

A Set of Japanese Word Cohorts Rated for Relative Familiarity

A SET OF JAPANESE WORD COHORTS RATED FOR RELATIVE FAMILIARITY Takashi Otake and Anne Cutler Dokkyo University and Max-Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics ABSTRACT are asked to guess about the identity of a speech signal which is in some way difficult to perceive; in gating the input is fragmentary, A database is presented of relative familiarity ratings for 24 sets of but other methods involve presentation of filtered or noise-masked Japanese words, each set comprising words overlapping in the or faint signals. In most such studies there is a strong familiarity initial portions. These ratings are useful for the generation of effect: listeners guess words which are familiar to them rather than material sets for research in the recognition of spoken words. words which are unfamiliar. The above list suggests that the same was true in this study. However, in order to establish that this was 1. INTRODUCTION so, it was necessary to compare the relative familiarity of the guessed words and the actually presented words. Unfortunately Spoken-language recognition proceeds in time - the beginnings of we found no existing database available for such a comparison. words arrive before the ends. Research on spoken-language recognition thus often makes use of words which begin similarly It was therefore necessary to collect familiarity ratings for the and diverge at a later point. For instance, Marslen-Wilson and words in question. Studies of subjective familiarity rating 1) 2) Zwitserlood and Zwitserlood examined the associates activated (Gernsbacher8), Kreuz9)) have shown very high inter-rater by the presentation of fragments which could be the beginning of reliability and a better correlation with experimental results in more than one word - in Zwitserlood's experiment, for example, language processing than is found for frequency counts based on the fragment kapit- which could begin the Dutch words kapitein written text. -

Shigisan Engi Shigisan Engi Overview

Shigisan engi Shigisan engi Overview I. The Shigisan engi or Legends of the Temple on Mount Shigi consists of three handscrolls. Scroll 1 is commonly called “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 2 “The Exorcism of the Engi Emperor,” and Scroll 3 “The Story of the Nun.” These scrolls are a pictorial presentation of three legends handed down among the common people. These legends appear under the title “Shinano no kuni no hijiri no koto” (The Sage of Shinano Province) in both the Uji sh¯ui monogatari (Tales from Uji) and the Umezawa version of the Kohon setsuwash¯u (Collection of Ancient Legends). Since these two versions of the legends are quite similar, one is assumed to be based on the other. The Kohon setsuwash¯u ver- sion is written largely in kana, the phonetic script, with few Chinese characters and is very close to the text of the Shigisan engi handscrolls. Thus, it seems likely that there is a deep connection between the Shigisan engi and the Kohon setsuwash¯u; one was probably the basis for the other. “The Flying Granary,” Scroll 1 of the Shigisan engi, lacks the textual portion, which has probably been lost. As that suggests, the Shigisan engi have not come down to us in their original form. The Shigisan Ch¯ogosonshiji Temple owns the Shigisan engi, and the lid of the box in which the scrolls were stored lists two other documents, the Taishigun no maki (Army of Prince Sh¯otoku-taishi) and notes to that scroll, in addition to the titles of the three scrolls. -

A World Like Ours: Gay Men in Japanese Novels and Films

A WORLD LIKE OURS: GAY MEN IN JAPANESE NOVELS AND FILMS, 1989-2007 by Nicholas James Hall A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Nicholas James Hall, 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines representations of gay men in contemporary Japanese novels and films produced from around the beginning of the 1990s so-called gay boom era to the present day. Although these were produced in Japanese and for the Japanese market, and reflect contemporary Japan’s social, cultural and political milieu, I argue that they not only articulate the concerns and desires of gay men and (other queer people) in Japan, but also that they reflect a transnational global gay culture and identity. The study focuses on the work of current Japanese writers and directors while taking into account a broad, historical view of male-male eroticism in Japan from the Edo era to the present. It addresses such issues as whether there can be said to be a Japanese gay identity; the circulation of gay culture across international borders in the modern period; and issues of representation of gay men in mainstream popular culture products. As has been pointed out by various scholars, many mainstream Japanese representations of LGBT people are troubling, whether because they represent “tourism”—they are made for straight audiences whose pleasure comes from being titillated by watching the exotic Others portrayed in them—or because they are made by and for a female audience and have little connection with the lives and experiences of real gay men, or because they circulate outside Japan and are taken as realistic representations by non-Japanese audiences. -

Catalogue Festival International Ciné

sommaire / summary PRÉSENTATION GÉNÉRALE PRESENTATION GENERALE 48 Monstres / Monsters 3 Sommaire / Summary 51 Soirée courts métrages « Attaque des PsychoZombies » / 4 Editos / Forewords "PsychoZombies’ Attack" short films night 12 Jurys officiels / Official juries 16 Invités / Guests 18 Cérémonies d'ouverture et de palmarès / Opening and HOMMAGE ANIME AU STUDIO GHIBLI palmares ceremonies 52 Conférence / Conference 20 Fête des enfants / Kids party 52 Rétrospective Studio Ghibli / Retrospective 55 Exposition - « Hayao Miyazaki en presse » / Exhibition COMPETITIONS INTERNATIONALES 22 Longs métrages inédits / Unreleased feature films AUTOUR DES FILMS 32 Courts métrages ados / Teenager short films 56 Séminaire « Les outils numériques dans l’éducation à 34 Courts métrages d'animation / Short animated films l’image » / Seminar 57 Ateliers et animations / Workshops and activities 60 Rencontres et actions éducatives / Meetings and educational INEDITS ET AVANT-PREMIERES HORS actions COMPETITION 65 Décentralisation / Decentralization 38 Ciné-bambin / Toddlers film 38 Séances scolaires et familles / School and family screenings 43 Séances scolaires et ado-adultes / Youth and adults screenings INFOS PRATIQUES 66 Equipe et remerciements / Team and thanks 68 Contacts / Print sources THEMATIQUE «CINEMA FANTASTIQUE» 70 Lieux du festival / Venues 44 Ciné-concert / Concert film 72 Réservations et tarifs / Booking and prices 45 Robots et mondes futuristes / Robots and futuristic worlds 74 Grille programme à Saint-Quentin / Schedule in Saint-Quentin 46 Magie, contes et mondes imaginaires / Magic, tales and 78 Index / Index imaginary worlds 79 Partenaires / Partnerships and sponsors éditos / foreword Une 33ème édition sous le Haut-Patronage de Madame Najat VALLAUD- BELKACEM, Ministre de l'éducation nationale, de l'enseignement supérieur et de la recherche. Ciné-Jeune est fantastique ! L’édition 2015 du Festival s’est donné pour thème le « Cinéma fantastique ». -

Nihonbashi: Edo's Contested Center Marcia Yonemoto

, East Asian History NUMBERS 17/18· JUNE/DECEMBER 1999 Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University 1 Editor Geremie R. Barme Assistant Editor Helen Lo Editorial Board Mark Elvin (Convenor) John Clark Andrew Fraser Helen Hardacre Colin Jeffcott W. ]. F. Jenner Lo Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Design and Production Helen Lo Business Manager Marion Weeks Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This double issue of East Asian History, 17/18, was printed in FebrualY 2000. Contributions to The Editor, East Asian History Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Phone +61 26249 3140 Fax +61 26249 5525 email [email protected] Subscription Enquiries to Subscriptions, East Asian History, at the above address Annual Subscription Australia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Whose Strange Stories? P'u Sung-ling (1640-1715), Herbert Giles (1845- 1935), and the Liao-chai chih-yi John Minford and To ng Man 49 Nihonbashi: Edo's Contested Center Marcia Yonemoto 71 Was Toregene Qatun Ogodei's "Sixth Empress"? 1. de Rachewiltz 77 Photography and Portraiture in Nineteenth-Century China Regine Thiriez 103 Sapajou Richard Rigby 131 Overcoming Risk: a Chinese Mining Company during the Nanjing Decade Ti m Wright 169 Garden and Museum: Shadows of Memory at Peking University Vera Schwarcz iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing M.c�J�n, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover illustration Talisman-"Passport for wandering souls on the way to Hades," from Henri Dore, Researches into Chinese superstitions (Shanghai: T'usewei Printing Press, 1914-38) NIHONBASHI: EDO'S CONTESTED CENTER � Marcia Yonemoto As the Tokugawa 11&)II regime consolidated its military and political conquest Izushi [Pictorial sources from the Edo period] of Japan around the turn of the seventeenth century, it began the enormous (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo, 1975), vol.4; project of remaking Edo rI p as its capital city. -

Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By

Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Japanese Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair Professor Alan Tansman Professor Beate Fricke Summer 2018 © 2018 Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe All Rights Reserved Abstract Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature by Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair My dissertation investigates the role of images in shaping literary production in Japan from the 1880’s to the 1930’s as writers negotiated shifting relationships of text and image in the literary and visual arts. Throughout the Edo period (1603-1868), works of fiction were liberally illustrated with woodblock printed images, which, especially towards the mid-19th century, had become an essential component of most popular literature in Japan. With the opening of Japan’s borders in the Meiji period (1868-1912), writers who had grown up reading illustrated fiction were exposed to foreign works of literature that largely eschewed the use of illustration as a medium for storytelling, in turn leading them to reevaluate the role of image in their own literary tradition. As authors endeavored to produce a purely text-based form of fiction, modeled in part on the European novel, they began to reject the inclusion of images in their own work. -

Hunger on the Rise in Corporate America Try Where Five Years of a Bloody Campaign Led by the Regime in Riyadh Have Shattered the Health System

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 12 Pages Price 40,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 39th year No.13638 Monday APRIL 13, 2020 Farvardin 25, 1399 Sha’aban 19, 1441 Iran says investigating Afghanistan thanks Iran Can the Iranian Top Iranian scholar possibility of coronavirus for free services to refugees clubs ask players to Hassan Anusheh as biological warfare 3 during COVID-19 10 take pay cut? 11 passes away at 75 12 Tax income up 31% in a year TEHRAN — Iran’s tax revenue has as value added tax (VAT)”, IRIB reported. increased 31 percent in the past Ira- Parsa also said that the country has nian calendar year (ended on March gained projected tax income by 102 percent Hunger on the rise 19), Omid- Ali Parsa, the head of Iran’s in the past year, and put the average tax National Tax Administration (INTA), income growth at 21 percent during the announced. previous five years. Putting the country’s tax income at 1.43 The head of National Tax Administra- quadrillion rials (about $34.04 billion) in tion further mentioned preventing from tax the previous year, the official said, “We could evasion as one of the prioritized programs collect 250 trillion rials (about $5.9 billion) of INTA. 4 in corporate See page 3 Discover Ozbaki hill that goes down 9,000 years in history America TEHRAN — “Nine thousand years of his- Ozbaki hill indicate some kind of com- tory.” It’s a phrase that may seem enough mercial link between Susa in Khuzestan to draw the attention of every history buff and this in Tehran province,” according across the globe. -

Masaki Kobayashi: HARAKIRI (1962, 133M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

October 8, 2019 (XXXIX: 7) Masaki Kobayashi: HARAKIRI (1962, 133m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Masaki Kobayashi WRITING Shinobu Hashimoto wrote the screenplay from a novel by Yasuhiko Takiguchi. PRODUCER Tatsuo Hosoya MUSIC Tôru Takemitsu CINEMATOGRAPHY Yoshio Miyajima EDITING Hisashi Sagara The film was the winter of the Jury Special Prize and nominated for the Palm d’Or at the 1963 Cannes Film Festival. CAST Tatsuya Nakadai...Tsugumo Hanshirō (1979), Tokyo Trial* (Documentary) (1983), and Rentarō Mikuni...Saitō Kageyu Shokutaku no nai ie* (1985). He also wrote the screenplays Akira Ishihama...Chijiiwa Motome for A Broken Drum (1949) and The Yotsuda Phantom Shima Iwashita...Tsugumo Miho (1949). Tetsurō Tamba...Omodaka Hikokuro *Also wrote Ichiro Nakatani...Yazaki Hayato Masao Mishima...Inaba Tango SHINOBU HASHIMOTO (b. April 18, 1918 in Hyogo Kei Satō...Fukushima Masakatsu Prefecture, Japan—d. July 19, 2018 (age 100) in Tokyo, Yoshio Inaba...Chijiiwa Jinai Japan) was a Japanese screenwriter (71 credits). A frequent Yoshiro Aoki...Kawabe Umenosuke collaborator of Akira Kurosawa, he wrote the scripts for such internationally acclaimed films as Rashomon (1950) MASAKI KOBAYASHI (b. February 14, 1916 in and Seven Samurai (1954). These are some of the other Hokkaido, Japan—d. October 4, 1996 (age 80) in Tokyo, films he wrote for: Ikiru (1952), -

The Geobiology and Ecology of Metasequoia

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/37160841 The Geobiology and Ecology of Metasequoia. Article · January 2005 Source: OAI CITATIONS READS 11 457 3 authors: Ben LePage Christopher J. Williams Pacific Gas and Electric Company Franklin and Marshall College 107 PUBLICATIONS 1,864 CITATIONS 55 PUBLICATIONS 1,463 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Hong Yang Massey University 54 PUBLICATIONS 992 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Conifer (Pinaceae and Cupressaceae (Taxodiaceae)) systematics and phylogeny View project All content following this page was uploaded by Ben LePage on 24 September 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Chapter 1 The Evolution and Biogeographic History of Metasequoia BEN A. LePAGE1, HONG YANG2 and MIDORI MATSUMOTO3 1URS Corporation, 335 Commerce Drive, Suite 300, Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, 19034, USA; 2Department of Science and Technology, Bryant University, 1150 Douglas Pike, Smithfield, Rhode Island, 02917, USA; 3Department of Earth Sciences, Chiba University, Yayoi-cho 133, Inage-ku, Chiba 263, Japan. 1. Introduction .............................................................. 4 2. Taxonomy ............................................................... 6 3. Morphological Stasis and Genetic Variation ................................. 8 4. Distribution of Metasequoia Glyptostroboides ............................... 10 5. Phytogeography ......................................................... -

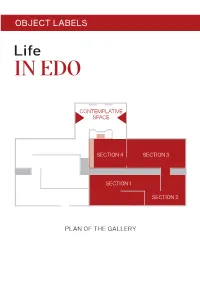

Object Labels

OBJECT LABELS CONTEMPLATIVE SPACE SECTION 4 SECTION 3 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 PLAN OF THE GALLERY SECTION 1 Travel Utagawa Hiroshige Procession of children passing Mount Fuji 1830s Hiroshige playfully imitates with children a procession of a daimyo passing Mt Fuji. A popular subject for artists, a daimyo and his entourage could make for a lively scene. During Edo, daimyo were required to travel to Edo City every other year and live there under the alternate attendance (sankin- kōtai) system. Hundreds of retainers would transport weapons, ceremonial items, and personal effects that signal the daimyo’s military and financial might. Some would be mounted on horses; the daimyo and members of his family carried in palanquins. Cat. 5 Tōshūsai Sharaku Actor Arashi Ryūzō II as the Moneylender Ishibe Kinkichi 1794 Kabuki actor portraits were one of the most popular types of ukiyo-e prints. Audiences flocked to see their favourite kabuki performers, and avidly collected images of them. Actors were stars, celebrities much like the idols of today. Sharaku was able to brilliantly capture an actor’s performance in his expressive portrayals. This image illustrates a scene from a kabuki play about a moneylender enforcing payment of a debt owed by a sick and impoverished ronin and his wife. The couple give their daughter over to him, into a life of prostitution. Playing a repulsive figure, the actor Ryūzō II made the moneylender more complex: hard-hearted, gesturing like a bully – but his eyes reveal his lack of confidence. The character is meant to be disliked by the audience, but also somewhat comical.