Rethinking Linguistic Unification, Spanning Political Heterogeneity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E:\Review\Or-2021\Or Feb-March

ISSN 0970-8669 Odisha Review Political Evolution in Ex-Princely State of Patna Under the Dynamic Leadership of Maharaja Rajendra Narayan Singh Deo Dr. Suresh Prasad Sarangi Abstract: (The ex-princely State of Patna was ruled by Maharaja Rajendra Narayan Singh Deo from 1931 to 1948. During his tenure as Maharaja, Sri Singh Deo tried to introduce a number of democratic reforms for the smooth working and good governance of Patna State. This article is a modest approach to unravel the dynamic administration unleashed by Maharaja Sri Singh Deo in ex-princely state of Patna during his tenure as Maharaja) Keywords: (Governance, Political identity, Suzerain Powers, Democratic set up, feudatory state) Introduction: Deo and Rajendra Narayan Singh Deo were most The history of Patna State dates back to popular and benevolent ruler of the ex-princely Ramai Deo, the real founder of the state who state of Patna. History always remembers founded the Chauhan dynasty in 1320 A.D. Chauhan dynasty of Patna State for their own approximately. But special identity and heroism. It Ramachandra Mallick could maintain its own special argued that the real state of identity in the history of Patna came into exist in the contemporary era and year 1159 A.D. Prior to the particularly out of twenty-six rule of Ramai Deo, the State feudatory states of Odisha of Patna was ruled by the whose existence was found at eight Mullicks or Pradhan. the time of their merger into the This system came to an end Indian Union. Thus, Patna state when Ramai Deo killed all was one of the premier states the Pradhans and declared of all the princely states in himself as the king of Patna. -

Ancient Hindu Rock Monuments

ISSN: 2455-2631 © November 2020 IJSDR | Volume 5, Issue 11 ANCIENT HINDU ROCK MONUMENTS, CONFIGURATION AND ARCHITECTURAL FEATURES OF AHILYA DEVI FORT OF HOLKAR DYNASTY, MAHISMATI REGION, MAHESHWAR, NARMADA VALLEY, CENTRAL INDIA Dr. H.D. DIWAN*, APARAJITA SHARMA**, Dr. S.S. BHADAURIA***, Dr. PRAVEEN KADWE***, Dr. D. SANYAL****, Dr. JYOTSANA SHARMA***** *Pt. Ravishankar Shukla University Raipur C.G. India. **Gurukul Mahila Mahavidyalaya Raipur, Pt. R.S.U. Raipur C.G. ***Govt. NPG College of Science, Raipur C.G. ****Architectural Dept., NIT, Raipur C.G. *****Gov. J. Yoganandam Chhattisgarh College, Raipur C.G. Abstract: Holkar Dynasty was established by Malhar Rao on 29th July 1732. Holkar belonging to Maratha clan of Dhangar origin. The Maheshwar lies in the North bank of Narmada river valley and well known Ancient town of Mahismati region. It had been capital of Maratha State. The fort was built by Great Maratha Queen Rajmata Ahilya Devi Holkar and her named in 1767 AD. Rani Ahliya Devi was a prolific builder and patron of Hindu Temple, monuments, Palaces in Maheshwar and Indore and throughout the Indian territory pilgrimages. Ahliya Devi Holkar ruled on the Indore State of Malwa Region, and changed the capital to Maheshwar in Narmada river bank. The study indicates that the Narmada river flows from East to west in a straight course through / lineament zone. The Fort had been constructed on the right bank (North Wards) of River. Geologically, the region is occupied by Basaltic Deccan lava flow rocks of multiple layers, belonging to Cretaceous in age. The river Narmada flows between Northwards Vindhyan hillocks and southwards Satpura hills. -

Dr. K. Sharada Professor Dept. of Kannada and Translation Studies Bhasha Bhavan, Srinivasa Vanam, Dravidian University, Kuppam-517 426 Andhra Pradesh, India

CV – Dr. (Mrs). K.Sharada GENERAL INFORMATION: Name : Dr.K.Sharada, M.A., M.Phil. Ph.D. (Kannada) Address for correspondence : Dr. K. Sharada Professor Dept. of Kannada and Translation Studies Bhasha Bhavan, Srinivasa Vanam, Dravidian University, Kuppam-517 426 Andhra Pradesh, India Phone : 09441209548 Sex : Female Date of Birth : 25.07.1963 Place of Birth : Hospet, Karnataka, India Religion : Hindu Caste & Category : Kamma Nationality : Indian Present Designation : Professor Mother Tongue : Telugu First Language : Kannada EDUCATIONAL QULIFICATIONS: B.A. : Gulbarga University, 1986 M.A. : Gulbarga University, 1990 M.Phil : Gulbarga University, 1991 Topic : Shasanokta Jaina Mahileyaru (Inscriptionalized Jain women) Ph.D. : Gulbarga University, 2005 Topic : Karnataka Samskritige Jainacharyara Koduge (Contribution of Jain Saints to the Karnataka Culture) 1 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: a. Teaching Experience: i. On Regular Service : 25 Years 2008 June - till date Professor Dept. of Kannada and Translation Studies Dravidian University, Kuppam 2005 – 2008 June Associate Professor Dept. of Kannada Studies, PG Centre Gulbarga University, Yeragera Campus Raichur, Karnataka 2003 Feb- 2005 Selection Grade Lecturer Dept. of Kannada Studies, PG Centre Gulbarga University, Yeragera Campus Raichur, Karnataka 1993-2002 Sep Lecturer in Kannada Dept. of Kannada Studies, PG Centre Gulbarga University, Krishnadevaraya Nagar Sandur Campus, Karnataka ii. On Temporary Service : 02 Years 1992 Sep-Jan 1993 Guest Lecturer in Kannada Dept. of Kannada Studies, PG Centre Gulbarga University, Krishnadevaraya Nagar Sandur Campus, Karnataka 1991-1092 Temporary Lecturer in Kannada Theosophical Women First Grade College Hospet, Karnataka. b. Research Experience : 28 years i. Other than Ph.D. : 14 Years ii. Ph.D. : 14 Years c. Administrative Experience 1. Dean, School of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies, Draviain Univeristy Kuppam from 04.05.2018 to 24.10.2018. -

MGM College Calender 2019-20

¸ÀvÁÛ÷évï ¸ÀAeÁAiÀÄvÉà eÁÕ£ÀA'' Mahatma Gandhi Memorial College '' Mahatma Gandhi Memorial P. U. College Kunjibettu, Udupi - 576 102, Karnataka, INDIA 70 Years of Academic Excellence Calendar & Hand Book 2019-2020 Our Founder Padmashree Dr. T.M.A. PAI (1898 - 1979) M.G.M. College VISION A student of Mahatma Gandhi Memorial College will be an individual endowed with a spirit of enquiry, eager to acquire knowledge and skills, competent to be employed in his field, possessing qualities of leadership, responsible to family, society and nation, capable of appreciating aesthetics and understanding our cultural heritage and rational as well as humane in attitude. MISSION The Mahatma Gandhi Memorial College strives to provide students with quality education using innovative and humane methods of teaching and learning, to develop in them competence for employment as well as entrepreneurship, to promote their power of thinking and creative ability, to organize activities that will contribute to the understanding of their responsibilities to the family the society and the nation and to promote national integration through cordial relationship between and among stake holders. Under the aegis of the Academy of General Education, Manipal, the College has been well nurtured by the Mahatma Gandhi Memorial College Trust and College Governing Council, both of which have contributed a lot to shaping of this college as an “Institution of academic and cultural distinction”. We are proud to say that the MGM alumni constitute a considerable part of the Indian -

ಕ ೋವಿಡ್ ಲಸಿಕಾಕರಣ ಕ ೋೇಂದ್ರಗಳು (COVID VACCINATION CENTRES) Sl No District CVC Na

ಕ ೋ풿蓍 ಲಕಾಕರಣ ಕ ೋᲂ飍ರಗಳು (COVID VACCINATION CENTRES) Sl No District CVC Name Category 1 Bagalkot SC Karadi Government 2 Bagalkot SC TUMBA Government 3 Bagalkot Kandagal PHC Government 4 Bagalkot SC KADIVALA Government 5 Bagalkot SC JANKANUR Government 6 Bagalkot SC IDDALAGI Government 7 Bagalkot PHC SUTAGUNDAR COVAXIN Government 8 Bagalkot Togunasi PHC Government 9 Bagalkot Galagali Phc Government 10 Bagalkot Dept.of Respiratory Medicine 1 Private 11 Bagalkot PHC BENNUR COVAXIN Government 12 Bagalkot Kakanur PHC Government 13 Bagalkot PHC Halagali Government 14 Bagalkot SC Jagadal Government 15 Bagalkot SC LAYADAGUNDI Government 16 Bagalkot Phc Belagali Government 17 Bagalkot SC GANJIHALA Government 18 Bagalkot Taluk Hospital Bilagi Government 19 Bagalkot PHC Linganur Government 20 Bagalkot TOGUNSHI PHC COVAXIN Government 21 Bagalkot SC KANDAGAL-B Government 22 Bagalkot PHC GALAGALI COVAXIN Government 23 Bagalkot PHC KUNDARGI COVAXIN Government 24 Bagalkot SC Hunnur Government 25 Bagalkot Dhannur PHC Covaxin Government 26 Bagalkot BELUR PHC COVAXINE Government 27 Bagalkot Guledgudd CHC Covaxin Government 28 Bagalkot SC Chikkapadasalagi Government 29 Bagalkot SC BALAKUNDI Government 30 Bagalkot Nagur PHC Government 31 Bagalkot PHC Malali Government 32 Bagalkot SC HALINGALI Government 33 Bagalkot PHC RAMPUR COVAXIN Government 34 Bagalkot PHC Terdal Covaxin Government 35 Bagalkot Chittaragi PHC Government 36 Bagalkot SC HAVARAGI Government 37 Bagalkot Karadi PHC Covaxin Government 38 Bagalkot SC SUTAGUNDAR Government 39 Bagalkot Ilkal GH Government -

Dr. Virupakshi Poojarahally

1. Name : Dr. Virupakshi Poojarahalli 2. Date of birth, Address : 17.8.1970 (Forty-nine years), KB Hatti, Poojarahalli 3. Father-mother : PalaIiah-Chinnamma 4. Reservation : Scheduled Tribe, Valmiki (Nayaka) Resident of Hyderabad Karnataka Region (371 J) 5. Present Position : Professor, Department of History 6. Basic Salary : Rs. 51,931.00 (10,000 + 81512 + 5994 total 1,52,441.00) (UGC Pay Grade Rs.37,400-67000) 7. Office (Postal) Address : Dept. of History., Kannada University, Hampi, Vidyaaranya, Hospet Taluk, Bellary District, Karnataka State- 583276 8. Permanent Address : Dr. Virupakshi Poojarahalli S / o Palayya KB Hatti, Poojarahalli Post Koodligi Taluk, Bellary Dist., Pincode: 583 218 94482-27156 EMail: [email protected] Residence Address : Pampadri Nivasa, Plot No. 21 Gokul Nagar, PDIT College Road Saibaba Gudi Area, Hospet - 583221, Bellary Dist. 9. Qualification A. MA (1992-94) (History and archeology) Kuvempu University, BR Project Shimoga 577 451, Karnataka B. M. Phil (1994-95) (Collector's rule in Bellary district (1800-1947): a survey) History Dept., Kannada University, Hampi 1 Vidyanya 583 276 C. Ph.D. (1995-2000) Hunting and Beda’s Described in Medieval Kannada Poetry: A Historical Study Kannada University, Hampi, Vidyanya 583 276 D. NET Examination (1996) 10. A. Service experience 20 years (Associate, Reade, Senior Grade Lecturer,Asst. Professor and Professor of Total Years 21) 10. B. Research experience 24 years a. Research student (1994-95) History Dept., Kannada University, Hampi Vidyanya 583 276 b. Research Assistant (1995-96) c. Assistant Teacher (1996-97) Government Higher Primary School, Elubenchi Bellary taluk and district d. Leacturer (16.8.1997 to 16.8.2001) History Dept., Kannada University, Hampi Vidyanya 583 276 e. -

Pre-Feasibility Report and Draft Terms of Reference

PRE-FEASIBILITY REPORT AND DRAFT TERMS OF REFERENCE OF EXPANSION OF TUBACHI BABALESHWARA LIFT IRRIGATION SCHEME TO EXPAND A COMMAND AREA FROM 42,500 TO 52,700 Ha NEAR KAVATAGI VILLAGE, JAMAKHANDI TALUK, BAGALKOT DISTRICT SCHEDULE 1(C) OF EIA NOTIFICATION, 2006, CATEGORY – A, TOTAL COST OF THE PROJECT – 3572.00 CRORES Submitted to THE DIRECTOR AND MEMBER SECRETARY, RIVER VALLEY AND HYDROELECTRIC PROJECTS, MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FORESTS AND CLIMATE CHANGE (MOEF), GOVT. OF INDIA NEW DELHI - 110003. Submitted by THE CHIEF ENGINEER KARNATAKA NEERAVARI NIGAMA LTD., IRRIGATION NORTH ZONE BELAGAVI – 590001 KARNATAKA Prepared by ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH & SAFETY CONSULTANTS PVT LTD # 13/2, 1ST MAIN ROAD, NEAR FIRE STATION, NABET/ EIA/ RA080/ 55 Dated: 03.12.2015 INDUSTRIAL TOWN, RAJAJINAGAR,BENGALURU-560 010, KARNATAKA SEPTEMBER 2017 Expansion of Tubachi-Babaleshwara Lift Irrigation Scheme PFR & Draft ToRs near Kavatagi village, Jamakhandi taluk, Bagalkot District Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary ......................................................................... 1 2. Introduction of the Project/ Background Information .......................... 3 3. Project Description .........................................................................15 4. Site Analysis ..................................................................................27 5. Planning ........................................................................................28 6. Proposed Infrastructure ................................................................. -

Maleru (ಮಲ ೇರು माले셁) Mystery Resolved

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 5, Ver. V (May. 2015), PP 06-27 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Scheduling of Tribes: Maleru (ಮಲ ೇರು माले셁) Mystery Resolved V.S.Ramamurthy1 M.D.Narayanamurthy2 and S.Narayan3 1,2,3(No 422, 9th A main, Kalyananagar, Bangalore - 560043, Karnataka, India) Abstract: The scheduling of tribes of Mysore state has been done in 1950 by evolving a list of names of communities from a combination of the 1901 Census list of Animist-Forest and Hill tribes and V.R.Thyagaraja Aiyar's Ethnographic glossary. However, the pooling of communites as Animist-Forest & Hill tribes in the Census had occurred due to the rather artificial classification of castes based on whether they were not the sub- caste of a main caste, their occupation, place of residence and the fictitious religion called ‘Animists’. It is not a true reflection of the so called tribal characteristics such as exclusion of these communities from the mainstrream habitation or rituals. Thus Lambáni, Hasalaru, Koracha, Maleru (Máleru ಮಲ ೇರು माले셁‘sic’ Maaleru) etc have been categorized as forest and hill tribes solely due to the fact that they neither belonged to established castes such as Brahmins, Vokkaligas, Holayas etc nor to the occupation groups such as weavers, potters etc. The scheduling of tribes of Mysore state in the year 1950 was done by en-masse inclusion of some of those communities in the ST list rather than by the study of individual communities. -

An Analysis of Kannada Language Newspapers, Magazines and Journals: 2008-2017

International Journal of Library and Information Studies Vol.8(2) Apr-Jun, 2018 ISSN: 2231-4911 An Analysis of Kannada Language Newspapers, Magazines and Journals: 2008-2017 Dr. K. Shanmukhappa Assistant Librarian Vijayanagara Sri Krishnadevaraya University Ballari, Karnataka e-mail: [email protected] Abstract – The paper presents the analysis of Kannada language newspapers, magazines and journals published during the 2008-2017 with help of Registrar of Newspapers for India (RNI) database is controlled by The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. Major findings are highest 13.23% publications published in 2012, following 11.85, 11.12% in 2014 and 2011 year, 10.97% in 2015, 10.90% in 2009, 10.17% in 2016, 10.38% in 2013 year published. Among 2843 publications, majority 46.4% monthly publications, 20.30% of the publications fortnight, 15.30% weekly publications, 14.46% daily publications. Among 30 districts, majority 26.70% of the publications published in Bangalore and 14.03% in Bengaluru urban district, and least 0.28% published in Vijayapura (Bijapur) district. It is important to study the Kannada literature publications for identifying the major developments and growth of the Kannada literature publications of Annual, Bi-Monthly, Daily, Daily Evening, Fortnightly, Four Monthly, Half Yearly, Monthly, Quarterly and Weekly’s were analysed in the study. Keywords: Kannda language publications, Registrar of Newspapers for India (RNI), Journalism, Daily newspapers, Magazines, Journals, Bibliometric studies. Introduction Information is an important element in every sector of life, be it social, economic, political, educational, industrial and technical development. In the present world, information is a very valuable commodity. -

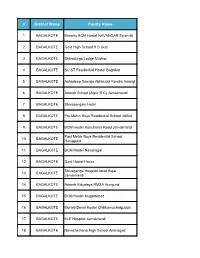

District Name Facilty Name

# District Name Facilty Name 1 BAGALKOTE Minority BCM Hostel NAVANGAR Sctor-46 2 BAGALKOTE Govt High School H S Gutti 3 BAGALKOTE Shivadurga Lodge Mudhol 4 BAGALKOTE SC ST Residential Hostel Bagalkot 5 BAGALKOTE Ashadeep Samaja Abhiruddi Kendra Asangi 6 BAGALKOTE Adarsh School (Algur R C) Jamakhandi 7 BAGALKOTE Shivasangam Hotel 8 BAGALKOTE Pre Metric Boys Residential School Jalihal 9 BAGALKOTE BCM Hostel Kunchanur Road Jamakhandi Post Metric Boys Residential School 10 BAGALKOTE Hunagund 11 BAGALKOTE BCM Hostel Navanagar 12 BAGALKOTE Govt Hostel Hosur Shivaganga Hospital Jolad Bajar 13 BAGALKOTE Jamakhandi 14 BAGALKOTE Adarsh Vidyalaya RMSA Hungund 15 BAGALKOTE BCM Hostel Mugalakhod 16 BAGALKOTE Morarji Desai Hostel Chikkamuchalgudda 17 BAGALKOTE KLE Hospital Jamakhandi 18 BAGALKOTE Navachethana High School Aminagad 19 BAGALKOTE Omkar Lodge Mudhol 20 BALLARI ROCK REGENCY 21 BALLARI MAYURA HOTEL 22 BALLARI KRK RESIDENCY 23 BALLARI VISHNU PRIYA HOTEL 24 BALLARI VIDYA RESIDENCY 25 BALLARI MD SCHOOL 26 BALLARI SIDDHARTH HOTEL 27 BELAGAVI Murarrji Desai School Katkol 28 BELAGAVI Hotel Rajdhani Sankeshwar 29 BELAGAVI New Lodge 30 BELAGAVI CHC Kabbur 31 BELAGAVI Pavan Hotel 32 BELAGAVI CHC Mudalagi 33 BELAGAVI Megha Lodge 34 BELAGAVI APMC Gokak Hostel METRIC NANTAR BALAKIYAR VIDYARTHI 35 BELAGAVI NILAY 36 BELAGAVI Morarji Desai High School Hulikatti 37 BELAGAVI S K LODGE 38 BELAGAVI Classic Lodge Kittur Rani Chennamma Girls Residential 39 BELAGAVI School, Chamakeri Maddi 40 BELAGAVI Priti Lodge Kudachi 41 BELAGAVI Murarji Desai High School Savadatti -

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41 10 Sep. 2015 | The Diplomat Highlight of Auction 39 63 64 133 111 90 96 97 117 78 103 110 112 138 122 125 142 166 169 Auction 41 The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins (with Proof & OMS Coins) Thursday, 10th September 2015 7.00 pm onwards VIEWING Noble Room Monday 7 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm The Diplomat Hotel Behind Taj Mahal Palace, Tuesday 8 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Opp. Starbucks Coffee, Wednesday 9 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Apollo Bunder At Rajgor’s SaleRoom Mumbai 400001 605 Majestic Shopping Centre, Near Church, 144 JSS Road, Opera House, Mumbai 400004 Thursday 10 Sept. 2015 3:00 pm - 6:30 pm At the Diplomat Category LOTS Coins of Mughal Empire 1-75 DELIVERY OF LOTS Coins of Independent Kingdoms 76-80 Delivery of Auction Lots will be done from the Princely States of India 81-202 Mumbai Office of the Rajgor’s. European Powers in India 203-236 BUYING AT RAJGOR’S Republic of India 237-245 For an overview of the process, see the Easy to buy at Rajgor’s Foreign Coins 246-248 CONDITIONS OF SALE Front cover: Lot 111 • Back cover: Lot 166 This auction is subject to Important Notices, Conditions of Sale and to Reserves To download the free Android App on your ONLINE CATALOGUE Android Mobile Phone, View catalogue and leave your bids online at point the QR code reader application on your www.Rajgors.com smart phone at the image on left side. -

Kannada Inscription from Maharashtra.Pdf

KANNADA INSCRIPTION FROM MAHARASHTRA Dr. Nalini Avinash Waghmare Department of History o Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune Mobile: 9975833748 Emailld:[email protected]. Introduction: From earlIest times Karnataka made its own impact in the lLil;tory of India. There wert! so many sources to focus on political. social, rel igion, cultw'al relations with other states. Kamataka's contribution to the culture of India is of prime importance. Kamata.ka and Maha rashtra are both neighbouring States. From ancient times these two, KaImada and Marathi language, have had a cultural exchange. This is one of the reasons these two states are attached with each other. "In the North Indian historian view Deccan land means North part of Tungabhadra River. According to Tamil his torian North India means South part of Kaveri River. Because of this for the development of South Indian not mention Kamataka's role by hi storian". We find all over Maharashtra, sources which have kept KUlllataka al ive; approximately 300 Kannada inscriptions, Viragallu ( hero stones), temples, many Archaeological sources which find in digging, coins, stamps, sc ulpture, literature etc., focus on Kannada people's life. Slu'ikantashashtri, Saltore, Shamba Joshi, (S.B. Joshi). B.P. Desai, R.C. Hiremath, Srinivas Ritti, M.M. Kulburgi, Pandit Avalikar, MY Narasimhamurthi etc Kannada writers and Rajwade, Bhandarkar, Ranade. Setuma dhavrao Pagade, Dhanjay Gadgil, Ramachandra, C. Dher, D.V. Ap te etc. Marathi writers tried to focus on both these states History and Cultural relation between Kamataka and Maharashtra near Gurlasur. Lokmanya Tilak expresses his view about relationship of Kamataka and Maharashtra.