Malinalco, Toluca, Guerrero Y Morelos**

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Geophytic Peperomia (Piperaceae) Species from Mexico, Belize and Costa Rica

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 82: 357-382, 2011 New geophytic Peperomia (Piperaceae) species from Mexico, Belize and Costa Rica Nuevas especies geofíticas de Peperomia (Piperaceae) de México, Belice y Costa Rica Guido Mathieu1, Lars Symmank2, Ricardo Callejas3, Stefan Wanke2, Christoph Neinhuis2, Paul Goetghebeur1 and Marie-Stéphanie Samain1* 1Ghent University, Department of Biology, Research Group Spermatophytes, K.L. Ledeganckstr. 35, B-9000 Gent, Belgium. 2Technische Universität Dresden, Institut für Botanik, Plant Phylogenetics and Phylogenomics Group, D-01062 Dresden, Germany. 3Universidad de Antioquia, Instituto de Biología, AA 1226 Medellín, Colombia *Correspondent: [email protected] Abstract. Peperomia subgenus Tildenia is a poorly known group of geophytic species occurring in seasonal habitats in 2 biodiversity hot spots (Mexico-Guatemala and Peru-Bolivia) with few species reported from the countries in between. Recent fieldwork combined with detailed study of herbarium specimens of this subgenus in Mexico and Central America resulted in the discovery of 12 new species, which are here described and illustrated. In addition, 1 formerly published variety is raised to species rank. Distribution, habitat and phenology data and detailed comparisons with other species are included, as well as an identification key for all species belonging to this subgenus in the studied area. Key words: tuber, terrestrial, endemism, Tildenia. Resumen. Peperomia subgénero Tildenia es un grupo poco conocido de especies geofíticas de hábitats estacionales en 2 hotspots de biodiversidad (México-Guatemala y Perú-Bolivia) con pocas especies en los países de enmedio. El trabajo de campo realizado recientemente en México y América Central, combinado con un estudio detallado de ejemplares de herbario de este subgénero, resultó en el descubrimiento de 12 especies nuevas, que se describen e ilustran. -

The University of Chicago the History of Idolatry and The

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE HISTORY OF IDOLATRY AND THE CODEX DURÁN PAINTINGS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY BY KRISTOPHER TYLER DRIGGERS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2020 Copyright © 2020 by Kristopher Driggers All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ………..……………………………………………………………… iv ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………….. viii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .….………………………………...………………………….. ix INTRODUCTION: The History of Idolatry and the Codex Durán Paintings……………… 1 CHAPTER 1. Historicism and Mesoamerican Tradition: The Book of Gods and Rites…… 34 CHAPTER 2. Religious History and the Veintenas: Productive Misreadings and Primitive Survivals in the Calendar Paintings ………………………………………………………… 66 CHAPTER 3. Toward Signification: Narratives of Chichimec Religion in the Opening Paintings of the Historia Treatise…………………………………………………………… 105 CHAPTER 4. The Idolater Kings: Rulers and Religious History in the Later Historia Paintings……………………………………………………………………………. 142 CONCLUSION. Picturing the History of Idolatry: Four Readings ………………………… 182 BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………………………………. 202 APPENDIX: FIGURES ……………………………………………………………………... 220 iii LIST OF FIGURES Some images are not reproduced due to restrictions. Chapter 1 1.1 Image of the Goddess Chicomecoatl, Codex Durán Folio 283 recto…………………..220 1.2 Priests, Codex Durán Folio 273 recto………………………………………………......221 1.3 Quetzalcoatl with devotional offerings, Codex Durán folio 257 verso………………...222 1.4 Codex Durán image of Camaxtli alongside frontispiece of Motolinia manuscript (caption only)..……………………………………………………………………….....223 1.5 Priests drawing blood with a zacatlpayolli in the corner, Codex Durán folio 248….….224 1.6 Priests wearing garlands and expressively gesturing, Codex Durán folio 246 recto.…..225 1.7 Tezcatlipoca, Codex Durán folio 241 recto ..………………………………….……….226 1.8 Image from Trachtenbuch, Christoph Weiditz, pp. -

AZTEC ARCHITECTURE by MANUEL AGUILAR-MORENO, Ph.D

AZTEC ARCHITECTURE by MANUEL AGUILAR-MORENO, Ph.D. PHOTOGRAPHY: FERNANDO GONZÁLEZ Y GONZÁLEZ AND MANUEL AGUILAR-MORENO, Ph.D. DRAWINGS: LLUVIA ARRAS, FONDA PORTALES, ANNELYS PÉREZ, RICHARD PERRY AND MARIA RAMOS. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Symbolism TYPES OF ARCHITECTURE General Construction of Pyramid-Temples Temples Types of pyramids Round Pyramids Twin Stair Pyramids Shrines (Adoratorios ) Early Capital Cities City-State Capitals Ballcourts Aqueducts and Dams Markets Gardens BUILDING MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUES THE PRECINCT OF TENOCHTITLAN Introduction Urbanism Ceremonial Plaza (Interior of the Sacred Precinct) The Great Temple Myths Symbolized in the Great Temple Construction Stages Found in the Archaeological Excavations of the Great Temple Construction Phase I Construction Phase II Construction Phase III Construction Phase IV Construction Phase V Construction Phase VI Construction Phase VII Emperor’s Palaces Homes of the Inhabitants Chinampas Ballcourts Temple outside the Sacred Precinct OTHER CITIES Tenayuca The Pyramid Wall of Serpents Tomb-Altar Sta. Cecilia Acatitlan The Pyramid Teopanzolco Tlatelolco The Temple of the Calendar Temple of Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl Sacred Well Priests’ Residency The Marketplace Tetzcotzinco Civic Monuments Shrines Huexotla The Wall La Comunidad (The Community) La Estancia (The Hacienda) Santa Maria Group San Marcos Santiago The Ehecatl- Quetzalcoatl Building Tepoztlan The Pyramid-Temple of Tepoztlan Calixtlahuaca Temple of Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl The Tlaloc Cluster The Calmecac Group Ballcourt Coatetelco Malinalco Temple I (Cuauhcalli) – Temple of the Eagle and Jaguar Knights Temple II Temple III Temple IV Temple V Temple VI Figures Bibliography INTRODUCTION Aztec architecture reflects the values and civilization of an empire, and studying Aztec architecture is instrumental in understanding the history of the Aztecs, including their migration across Mexico and their re-enactment of religious rituals. -

BIBLIOGRAFÍA Lingüística NAHUA 411 Jos De Carácter Lingüístico

Ascensión H. de BIBLIOGRAFíA LINGUiSTICA NAHUA León-Portilla La presente bibliografía tiene como propósito registrar la mayor parte de los estudios que se han hecho sobre la lengua nahua, desde el siglo XVI hasta nuestros días, o mejor dicho, hasta el año de 1970. 1!:stos ya más de cuatro siglos han sido pródigos en trabajos lingüís• ticos mexicanistas de tal manera que mucho es 10 que se ha publicado sobre el tema y, por consiguiente, grande es el número de fichas incluidas. Seguramente habrá aquí omisiones, aunque involuntarias. Creemos haber recogido al menos un considerable caudal de trabajos con sus referencias, dadas con la mayor precisión que nos ha sido posible. El contenido de esta recopilación bibliográfica básicamente abarca toda clase de estudios sobre la lengua náhuatl y sus dialectos; es decir, artes o gramáticas, vocabularios o diccionarios, estudios de carácter fonético, morfológico y sintáctico, formas dialectales, glosa rios de voces de materias especializadas, nahuatlismos y obras rela tivas a la toponimia. No cubre, en cambio, esta bibliografía trabajos de otro tipo como son los sermonarios y diversos textos religiosos de evangelización, muy abundantes en la época colonial, ni la gran riqueza de los textos de carácter literario, histórico o religioso de origen prehispánico, ni las obras de los cronistas nahuas de los siglos XVI y xvn, así como tampoco los relatos, cuentos y otros testimonios de contenido etnográfico que modernamente se han recogido en gran número. Sería muy interesante una bibliografía que comprendiera todo esto. Un semejante proyecto, tan necesario, rebasa nuestras po sibilidades y, por el momento, nos hemos limitado a esta recopilación de materiales primariamente lingüísticos. -

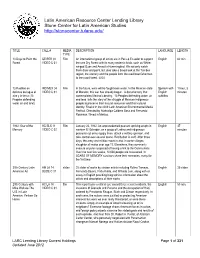

Latin American Resource Center Lending Library Stone Center for Latin American Studies

Latin American Resource Center Lending Library Stone Center for Latin American Studies http://stonecenter.tulane.edu/ TITLE CALL # MEDIA DESCRIPTION LANGUAGE LENGTH TYPE 10 Days to Paint the GE PER 02 Film An international group of artists are in Peru & Ecuador to support English 82 min Forest VIDEO C 01 the rare Dry Forest with its many endemic birds, such as White- winged Guan and Amazilia Hummingbird. We not only watch them draw and paint, but also take a broad look at the Tumbes region, the scenery and the people from the reed boat fishermen to the cloud forest. 2004 13 Pueblos en IND MEX 04 Film In the future, wars will be fought over water. In the Mexican state Spanish with 1 hour, 3 defensa del agua el VIDEO C 01 of Morelos, this war has already begun. A documentary that English minutes aire y la tierra (13 contemplates Mexico’s destiny, 13 Peoples defending water, air subtitles Peoples defending and land tells the story of the struggle of Mexican indigenous water air and land) people to preserve their natural resources and their cultural identity. Finalist in the 2009 Latin American Environmental Media Festival. Directed by Atahualpa Caldera Sosa and Fernanda Robinson. filmed in Mexico. 1932: Scar of the HC ELS 11 Film January 22, 1932. An unprecedented peasant uprising erupts in English 47 Memory VIDEO C 02 western El Salvador, as a group of Ladino and indigenous minutes peasants cut army supply lines, attack a military garrison, and take control over several towns. Retribution is swift. After three days, the army and militias move in and, in some villages, slaughter all males over age 12. -

Aztec Art PDF Part 2

AZTEC ART - Part 2 By MANUEL AGUILAR-MORENO, Ph.D. PHOTOGRAPHY: FERNANDO GONZÁLEZ Y GONZÁLEZ AND MANUEL AGUILAR-MORENO, Ph.D. DRAWINGS: LLUVIA ARRAS, FONDA PORTALES, ANNELYS PÉREZ AND RICHARD PERRY. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION THE AZTEC ARTISTS AND CRAFTSMEN Tolteca MONUMENTAL STONE SCULPTURE Ocelotl-Cuahxicalli Cuauhtli-Cuauhxicalli Dedication Stone Stone of the Warriors Bench Relief Teocalli of the Sacred War (Temple Stone) The Sun Stone The Stones of Tizoc and Motecuhzoma I Portrait of Motecuhzoma II Spiral Snail Shell (Caracol) Tlaltecuhtli (Earth God) Tlaltecuhtli del Metro (Earth God) Coatlicue Coatlicue of Coxcatlan Cihuacoatl Xiuhtecuhtli-Huitzilopochtli Coyolxauhqui Relief Head of Coyolxauhqui Xochipilli (God of Flowers) Feathered Serpent Xiuhcoatl (Fire Serpent Head) The Early Chacmool in the Tlaloc Shrine Tlaloc-Chacmool Chicomecoatl Huehueteotl Cihuateotl (Deified Woman) Altar of the Planet Venus Altar of Itzpaopalotl (Obsidian Butterfly) Ahuitzotl Box Tepetlacalli (Stone Box) with Figure Drawing Blood and Zacatapayolli Stone Box of Motecuhzoma II Head of an Eagle Warrior Jaguar Warrior Atlantean Warriors Feathered Coyote The Acolman Cross (Colonial Period, 1550) TERRACOTTA SCULPTURE Eagle Warrior Mictlantecuhtli Xipec Totec CERAMICS Vessel with a Mask of Tlaloc Funerary Urn with Image of God Tezcatlipoca Flutes WOOD ART Huehuetl (Vertical Drum) of Malinalco Teponaztli (Horizontal Drum) of Feline Teponaztli (Horizontal Drum) With Effigy of a Warrior Tlaloc FEATHER WORK The Headdress of Motecuhzoma II Feathered Fan Ahuitzotl Shield Chalice Cover Christ the Savior LAPIDARY ARTS Turquoise Mask Double-Headed Serpent Pectoral Sacrificial Knife Knife with an Image of a Face GOLD WORK FIGURES BIBLIOGRAPHY TERRACOTTA SCULPTURE For most cultures in Mesoamerica, terracotta sculpture was one of the principal forms of art during the Pre-Classic and Classic periods. -

Aztec Architecture Part II by Manuel Aguilar-Moreno

AZTEC ARCHITECTURE - Part 2 by MANUEL AGUILAR-MORENO, Ph.D. PHOTOGRAPHY: FERNANDO GONZÁLEZ Y GONZÁLEZ AND MANUEL AGUILAR-MORENO, Ph.D. DRAWINGS: LLUVIA ARRAS, FONDA PORTALES, ANNELYS PÉREZ, RICHARD PERRY AND MARIA RAMOS. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Symbolism TYPES OF ARCHITECTURE General Construction of Pyramid-Temples Temples Types of pyramids Round Pyramids Twin Stair Pyramids Shrines (Adoratorios ) Early Capital Cities City-State Capitals Ballcourts Aqueducts and Dams Markets Gardens BUILDING MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUES THE PRECINCT OF TENOCHTITLAN Introduction Urbanism Ceremonial Plaza (Interior of the Sacred Precinct) The Great Temple Myths Symbolized in the Great Temple Construction Stages Found in the Archaeological Excavations of the Great Temple Construction Phase I Construction Phase II Construction Phase III Construction Phase IV Construction Phase V Construction Phase VI Construction Phase VII Emperor’s Palaces Homes of the Inhabitants Chinampas Ballcourts Temple outside the Sacred Precinct OTHER CITIES Tenayuca The Pyramid Wall of Serpents Tomb-Altar Sta. Cecilia Acatitlan The Pyramid Teopanzolco Tlatelolco The Temple of the Calendar Temple of Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl Sacred Well Priests’ Residency The Marketplace Tetzcotzinco Civic Monuments Shrines Huexotla The Wall La Comunidad (The Community) La Estancia (The Hacienda) Santa Maria Group San Marcos Santiago The Ehecatl- Quetzalcoatl Building Tepoztlan The Pyramid-Temple of Tepoztlan Calixtlahuaca Temple of Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl The Tlaloc Cluster The Calmecac Group Ballcourt Coatetelco Malinalco Temple I (Cuauhcalli) – Temple of the Eagle and Jaguar Knights Temple II Temple III Temple IV Temple V Temple VI Figures Bibliography OTHER CITIES The Aztec empire was a large domain that extended from the Valley of Mexico to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec [ Figs. -

AZTEC ARCHITECTURE -Part 1 by MANUEL AGUILAR-MORENO, Ph.D

AZTEC ARCHITECTURE -Part 1 by MANUEL AGUILAR-MORENO, Ph.D. PHOTOGRAPHY: FERNANDO GONZÁLEZ Y GONZÁLEZ AND MANUEL AGUILAR-MORENO, Ph.D. DRAWINGS: LLUVIA ARRAS, FONDA PORTALES, ANNELYS PÉREZ, RICHARD PERRY AND MARIA RAMOS. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Symbolism TYPES OF ARCHITECTURE General Construction of Pyramid-Temples Temples Types of pyramids Round Pyramids Twin Stair Pyramids Shrines (Adoratorios) Early Capital Cities City-State Capitals Ballcourts Aqueducts and Dams Markets Gardens BUILDING MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUES THE PRECINCT OF TENOCHTITLAN Introduction Urbanism Ceremonial Plaza (Interior of the Sacred Precinct) The Great Temple Myths Symbolized in the Great Temple Construction Stages Found in the Archaeological Excavations of the Great Temple Construction Phase I Construction Phase II Construction Phase III Construction Phase IV Construction Phase V Construction Phase VI Construction Phase VII Emperor’s Palaces Homes of the Inhabitants Chinampas Ballcourts Temple outside the Sacred Precinct OTHER CITIES Tenayuca The Pyramid Wall of Serpents Tomb-Altar Sta. Cecilia Acatitlan The Pyramid Teopanzolco Tlatelolco The Temple of the Calendar Temple of Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl Sacred Well Priests’ Residency The Marketplace Tetzcotzinco Civic Monuments Shrines Huexotla The Wall La Comunidad (The Community) La Estancia (The Hacienda) Santa Maria Group San Marcos Santiago The Ehecatl- Quetzalcoatl Building Tepoztlan The Pyramid-Temple of Tepoztlan Calixtlahuaca Temple of Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl The Tlaloc Cluster The Calmecac Group Ballcourt Coatetelco Malinalco Temple I (Cuauhcalli) – Temple of the Eagle and Jaguar Knights Temple II Temple III Temple IV Temple V Temple VI Figures Bibliography INTRODUCTION Aztec architecture reflects the values and civilization of an empire, and studying Aztec architecture is instrumental in understanding the history of the Aztecs, including their migration across Mexico and their re-enactment of religious rituals. -

Redalyc.New Geophytic Peperomia (Piperaceae) Species from Mexico

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad ISSN: 1870-3453 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México Mathieu, Guido; Symmank, Lars; Callejas, Ricardo; Wanke, Stefan; Neinhuis, Christoph; Goetghebeur, Paul; Samain, Marie-Stéphanie New geophytic Peperomia (Piperaceae) species from Mexico, Belize and Costa Rica Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, vol. 82, núm. 2, junio, 2011, pp. 357-382 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=42521043002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 82: 357-382, 2011 New geophytic Peperomia (Piperaceae) species from Mexico, Belize and Costa Rica Nuevas especies geofíticas de Peperomia (Piperaceae) de México, Belice y Costa Rica Guido Mathieu1, Lars Symmank2, Ricardo Callejas3, Stefan Wanke2, Christoph Neinhuis2, Paul Goetghebeur1 and Marie-Stéphanie Samain1* 1Ghent University, Department of Biology, Research Group Spermatophytes, K.L. Ledeganckstr. 35, B-9000 Gent, Belgium. 2Technische Universität Dresden, Institut für Botanik, Plant Phylogenetics and Phylogenomics Group, D-01062 Dresden, Germany. 3Universidad de Antioquia, Instituto de Biología, AA 1226 Medellín, Colombia *Correspondent: [email protected] Abstract. Peperomia subgenus Tildenia is a poorly known group of geophytic species occurring in seasonal habitats in 2 biodiversity hot spots (Mexico-Guatemala and Peru-Bolivia) with few species reported from the countries in between. Recent fieldwork combined with detailed study of herbarium specimens of this subgenus in Mexico and Central America resulted in the discovery of 12 new species, which are here described and illustrated.