Aztec Art PDF Part 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CEM ANAHUAC CONQUERORS Guillermo Marín

THE CEM ANAHUAC CONQUERORS Guillermo Marín Dedicated to the professor and friend Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, who illuminated me in the darkest nights. Tiger that eats in the bowels of the heart, stain its jaws the bloody night, and grows; and diminished grows old he who waits, while far away shines an irremediable fire. Rubén Bonifaz Nuño. Summary: The Cem Ānáhuac conquest has been going on for five centuries in a permanent struggle, sometimes violent and explosive, and most of the time via an underground resistance. The military conquest began by Nahua peoples of the Highlands as Spanish allies in 1521. At the fall of Tenochtitlan by Ixtlilxóchitl, the Spanish advance, throughout the territory, was made up by a small group of Spaniards and a large army composed of Nahua troops. The idea that at the fall of Tenochtitlan the entire Cem Anahuac fell is false. During the 16th century the military force and strategies were a combination of the Anahuaca and European knowledge, because both, during the Viceroyalty and in the Mexican Republic, anahuacas rebellions have been constant and bloody, the conquest has not concluded, the struggle continues. During the Spanish colony and the two centuries of Creole neo-colonialism, the troop of all armies were and continues to be, essentially composed of anahuacas. 1. The warrior and the Toltecáyotl Flowered Battle. Many peoples of the different ancient cultures and civilizations used the "Warrior" figure metaphorically. The human being who fights against the worst enemy: that dark being that dwells in the personal depths. A fight against weaknesses, errors and personal flaws, as the Jihad in the Islam religion. -

FFP/Celebrate Text.Qdoc

FFP-CelebrateCYMK.doc:FFP/CelebrateCYMK_TXT 12/3/08 10:40 AM Page i CELEBRATE NATIVE AMERICA! An Aztec Book of Days FFP-CelebrateCYMK.doc:FFP/CelebrateCYMK_TXT 12/3/08 10:40 AM Page ii FFP-CelebrateCYMK.doc:FFP/CelebrateCYMK_TXT 12/3/08 10:40 AM Page iii CELEBRATE NATIVE AMERICA! An Aztec Book of Days Five Flower Press Santa Fe, New Mexico BY RICHARD BALTHAZAR FFP-CelebrateCYMK.doc:FFP/CelebrateCYMK_TXT 12/3/08 10:40 AM Page iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Front cover illustration: Sincere gratitude to Ernesto Torres for his incisive and insightful editing, to John HUITZILOPOCHTLI Cole for his artistry in processing and assembling the illustrations, and to the Uni- Hummingbird of the South versity of New Mexico Library for access to editions of several Aztec codices. The Aztec god of war. Publisher’s Cataloging in Publication (Prepared by Quality Books Inc.) Balthazar, Richard. Celebrate native America! : an Aztec book of days / Richard Balthazar. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-9632661-1-X 1. Aztec—Calendar. 2. Indians of Mexico—Calendar. 3. Aztecs—Religion and mythology. 4. Indians of Mexico—Religion and mythology. I. Title. II. Title: Aztec book of days. F1219.76.C35B38 1993 972.018 QB193–20421 ©1993, Richard Balthazar. All rights reserved. Printed in Korea. Design/Typography: John Cole Graphic Designer, Cerrillos, New Mexico U.S.A. Software used to produce this publication: Quark XPress 3.1, Adobe Streamline 2.0 and Adobe Illustrator 3.0. Typeface: Adobe Cochin. Printed on acid free paper. FFP-CelebrateCYMK.doc:FFP/CelebrateCYMK_TXT -

Notes on the Sacred Place Called the Coatlan by the Aztecs

NOTES ON THE SACRED PLACE CALLED THE COATLAN BY THE AZTECS There is a large plaza at Teotihuacan which lies at the the foot of the so-called Temple of the Moon. This Temple looms like a mountain at the northern terminus of the great north-south ceremonial way and is almost certainly a man-made model of that mountain which the Aztecs named "Tenan" meaning "Our Mother' or "Mother of Stone". As a sacred enclosure the plaza is second in size only to the Ciudadela toward the southern end of the ceremonial way which was by far the most prominent thoroughfare through the city of Teotihuacan. The Aztecs named it "The Road of the Dead". Although the original name of the plaza is lost to us, the significance of the space must have been clearly understood by the Aztecs. We know they had the most profound respect for Teotihuacan even though its ancient structures had lain in ruins for five hundred years before the nomadic tofeecs entered the Valley of Mexico. Like the mountain Tenan, the plaza and its temple honored the mother goddess, the giver of life and the devourer of the dead. She had many names and manifestations for the newcomers. Her most prestigious name among the new lords of the Valley of Mexico was "Cihuacoatl", "Woman-serpent", and in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan her temple and its enclosure was called the "Coatlan". As with Coatlans everywhere, the Aztecs saw the Plaza of the Moon as a the Place of Origins and Endings, both womb and tomb. -

Public Ritual Sacrifice As a Controlling Mechanism for the Aztec" (2017)

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Honors Scholar Theses Honors Scholar Program Spring 5-1-2017 Public Ritual Sacrifice sa a Controlling Mechanism for the Aztec Madeline Nicholson [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Folklore Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Nicholson, Madeline, "Public Ritual Sacrifice as a Controlling Mechanism for the Aztec" (2017). Honors Scholar Theses. 549. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/549 APRIL 2017 Public Ritual Sacrifice as a Controlling Mechanism for the Aztec MADELINE NICHOLSON UNIVERISITY OF CONNECTICUT Anthropology Honors Thesis Public Ritual Sacrifice 1 Introduction against the Mesoamerican archaeology. Help from other anthropologists such as: Catherine For decades, archaeologists have Bell, Pierre Bourdieu, Edmund Leach, Emile researched the fascinating finds of Aztec Durkheim, and Åsa Berggren supplement the sacrifice. Evidence of their sacrifices are seen two main theories. on temple walls, stone carvings, bones, and Rituals are the foundation of society. in Spanish chronicler drawings. Although They create an environment where laypeople public ritual sacrifice was practiced before lose their personal identity in favor of the the Aztecs, with evidence from the Olmec group. They reinforce social roles and civilization (1200-1300 BCE) and Maya ideologies through their performance. Pierre (200-900 BCE), Aztec sacrifices are among Bourdieu explains rituals through “practice the most extensively documented. How does theory where rituals are seen as expressions such a practice as human sacrifice survive in of meaning, as parts of a structuration process different civilizations through different where everything and everybody are tied rulers? This thesis will analyze the phases of together into a whole that is perceived as Aztec public ritual sacrifice and the close objective and true” (Bruck 1999: 176). -

Smith ME. Aztec Materials in Museum Collections

21 ******** Aztec Materials in Museum Collections: Some Frustrations of a Field Archaeologist by Michael E. Smith University at Albany, State University of New York In writing up the artifacts from my excavations in Morelos (Smith 2004a, b), I have run up against a roadblock in scholarship in Aztec archaeology and art history. Aztec objects are scattered in museums throughout the world, and there are few catalogs or comprehensive studies of particular classes of object (Smith 2003:6). This makes it difficult to find relevant comparative examples for my fragmentary artifacts, hindering efforts to interpret their forms, uses, and meanings. Most of the attention given to Aztec art focuses on a small number of fine objects, ignoring the range of variation in particular material categories. In this paper I provide a few examples of this problem with the hope that some colleagues will join me in finding a way to better publicize and study the many collections of Aztec artifacts and art. Stone sculpture, for example, is one of the most widely known and best published genres of Aztec art. Figure 1 shows a small human figure of basalt from the Aztec town of Cuexcomate in western Morelos (Smith 1992). One of several stone sculptures from the site, this piece was discovered on the surface of the ground, face down among rocks and debris, some distance from the nearest structure. It probably dates to the Aztec period (the only occupation at Cuexcomate), although it could be an Epiclassic sculpture from the nearby site of Xochicalco that was looted in Aztec times. -

Myths and Legends: the Feathered Serpent God 1 Storytimetm

TM Storytime Myths and Legends: The Feathered Serpent God 1 Teaching Resources The Feathered Serpent God is a myth from the Aztec civilisation IN BRIEF about one of their most important gods, Quetzalcoatl, and how he brought people to life. 1 LITERACY LESSON IDEAS The Feathered Serpent God is a good story to read alongside learning about the Aztec civilisation. Quetzalcoatl was an important and powerful god in ancient Central America. Find out more about him on our Quetzalcoatl Fact Sheet and find out about other Aztec gods in our Top 10 Aztec Gods Sheet. See our Feathered Serpent God Word Wise Sheet to find the meanings of any new or tricky words, and have a go at our Quick Comprehension Checker and writing exercises. Put this myth in the correct order using our Story Sequencing Sheet. Looking at the pictures, write the story in your own words using our Simple Storyboards. Make up your own myth to explain why humans come in different shapes and sizes. Discuss your ideas in class. Use our Storytime Writing Sheet to write it. Act out The Feathered Serpent God myth using our printable Quetzalcoatl, Xolotl and Skeleton Masks. The skeletons can be the Lord and Lady of the Underworld. 2 SCIENCE LESSON IDEAS Imagine you are Quetzalcoatl and you have to put the bones you’ve carried back together to make a human. Do you know where each bones goes? Fill in the blanks on our Super Skeleton Sheet and learn the names of some important bones too. Continued on page 2... © storytimemagazine.com 2018 TM Storytime Myths and Legends: The Feathered Serpent God 2 Teaching Resources 3 HISTORY LESSON IDEAS The Aztecs were fascinating. -

Editorial - Xólotl and Quetzalcóatl in Relation to Monstrosities of Maguey (Agave) and Teocentli (Zea), with Notes on the Pre-Columbian Religion of Mexico

Editorial - Xólotl and Quetzalcóatl in Relation to Monstrosities of Maguey (Agave) and Teocentli (Zea), with Notes on the Pre-Columbian Religion of Mexico Item Type Article Authors Crosswhite, F. S. Publisher University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Journal Desert Plants Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 30/09/2021 23:38:00 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/554215 This plant of Agave shawii in Baja California is a developmental monstrosity. As an addendum to the 1985 Symposium on the Genus Agave, Donald 1. Pinkava announced that John R. Pasek had requested the photograph' above to be projected on the screen. Some participants immediately thought of XÔLCYTL, the pre -Columbian deity who changed himself into a monstrosity of an Agave. As the audience marvelled at the Agave monstrosity on the screen, the plenary session was declared closed. stars of the heavens) gathered at TEOTIHUACÁN so that one could Editorial volunteer to be sacrificed to the sun. Not one but two gods volunteered, one rich and one poor. The rich XÓLOTL and QUETZALCÓATL in Relation to Monstrosities god offered fine possessions in sacrifice as preparation. The poor god of MAGUEY (Agave) and TEOCENTLI (Zea), With Notes on the offered only spines of MAGUEY (Agave) stained with his own blood. To Pre- Columbian Religion of Mexico. According to the Aztecs become the sun the god or gods had to leap into the flame of the and their predecessors in pre -Columbian Mexico there were several sacred brazier to emerge pure so as to illuminate the world. -

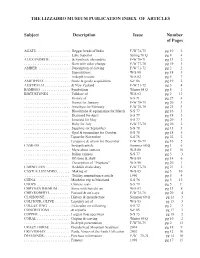

List of Articles

THE LIZZADRO MUSEUM PUBLICATION INDEX OF ARTICLES Subject Description Issue Number of Pages AGATE. .. Beggar beads of India F-W 74-75 pg 10 2 . Lake Superior Spring 70 Q pg 8 4 ALEXANDRITE . & Synthetic alexandrite F-W 70-71 pg 13 2 . Gem with color change F-W 77-78 pg 19 1 AMBER . Description of carving F-W 71-72 pg 2 2 . Superstitions W-S 80 pg 18 5 . in depth treatise W-S 82 pg 5 7 AMETHYST . Stone & geode acquisitions S-F 86 pg 19 2 AUSTRALIA . & New Zealand F-W 71-72 pg 3 4 BAMBOO . Symbolism Winter 68 Q pg 8 1 BIRTHSTONES . Folklore of W-S 93 pg 2 13 . History of S-S 71 pg 27 4 . Garnet for January F-W 78-79 pg 20 3 . Amethyst for February F-W 78-79 pg 22 3 . Bloodstone & aquamarine for March S-S 77 pg 16 3 . Diamond for April S-S 77 pg 18 3 . Emerald for May S-S 77 pg 20 3 . Ruby for July F-W 77-78 pg 20 2 . Sapphire for September S-S 78 pg 15 3 . Opal & tourmaline for October S-S 78 pg 18 5 . Topaz for November S-S 78 pg 22 2 . Turquoise & zircon for December F-W 78-79 pg 16 5 CAMEOS . In-depth article Summer 68 Q pg 1 6 . More about cameos W-S 80 pg 5 10 . Italian cameos S-S 77 pg 3 3 . Of stone & shell W-S 89 pg 14 6 . Description of “Neptune” W-S 90 pg 20 1 CARNELIAN . -

Toltec.Html Toltec

Text and pictures adapted from http://www.crystalinks.com/toltec.html Toltec The Atlantes are columns in the form of Toltec warriors in Tula The word Toltec in Mesoamerican studies has been used in different ways by different scholars to refer to actual populations and polities of pre-Columbian central Mexico or to the mythical ancestors mentioned in the mythical/historical narratives of the Aztecs. It is an ongoing debate whether the Toltecs can be understood to have formed an actual ethnic group at any point in Mesoamerican history or if they are mostly or only a product of Aztec myth. The scholars who have understood the Toltecs to have been an actual ethnic group often connect them to the archeological site of Tula, Hidalgo which is then supposed to have been the Tollan of Aztec myth. This tradition assumes the "Toltec empire" to have dominated much of central Mexico between the 10th and 12th century AD. Other Mexican cities such as Teotihuacán have also been proposed to have been the historical Tollan "Place of Reeds", the city from which the name Tolteca "inhabitant of Tollan" is derived in the Nahuatl language. The term Toltec has also been associated with the arrival of certain Central Mexican cultural traits into the Mayan sphere of dominance that took place in the late classic and early postclassic periods, and the Postclassic Mayan civilizations of Chichén Itzá, Mayapán and the Guatemalan highlands have been referred to as "toltecized" or "mexicanized" Mayas. For example the striking similarities between the city of Tula, Hidalgo and Chichen Itza have often been cited as direct evidence for Toltec dominance of the Postclassic Maya. -

God of the Month: Tlaloc

God of the Month: Tlaloc Tlaloc, lord of celestial waters, lightning flashes and hail, patron of land workers, was one of the oldest and most important deities in the Aztec pantheon. Archaeological evidence indicates that he was worshipped in Mesoamerica before the Aztecs even settled in Mexico's central highlands in the 13th century AD. Ceramics depicting a water deity accompanied by serpentine lightning bolts date back to the 1st Tlaloc shown with a jaguar helm. Codex Vaticanus B. century BC in Veracruz, Eastern Mexico. Tlaloc's antiquity as a god is only rivalled by Xiuhtecuhtli the fire lord (also Huehueteotl, old god) whose appearance in history is marked around the last few centuries BC. Tlaloc's main purpose was to send rain to nourish the growing corn and crops. He was able to delay rains or send forth harmful hail, therefore it was very important for the Aztecs to pray to him, and secure his favour for the following agricultural cycle. Read on and discover how crying children, lepers, drowned people, moun- taintops and caves were all important parts of the symbolism surrounding this powerful ancient god... Starting at the very beginning: Tlaloc in Watery Deaths Tamoanchan. Right at the beginning of the world, before the gods were sent down to live on Earth as mortal beings, they Aztecs who died from one of a list of the fol- lived in Tamoanchan, a paradise created by the divine lowing illnesses or incidents were thought to Tlaloc vase. being Ometeotl for his deity children. be sent to the 'earthly paradise' of Tlalocan. -

The Myths of Mexico and Peru

THE MYTHS OF MEXICO AND PERU by Lewis Spence (1913) This material has been reconstructed from various unverified sources of very poor quality and reproduction by Campbell M Gold CMG Archives http://campbellmgold.com --()-- 1 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Illustrations .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Map of the Valley of Mexico ................................................................................................................ 3 Ethnographic Map of Mexico ............................................................................................................... 4 Detail of Ethnographic Map of Mexico ................................................................................................. 5 Empire of the Incas .............................................................................................................................. 6 Preface .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1 - The Civilisation of Mexico .................................................................................................... 9 Chapter 2 - Mexican Mythology ........................................................................................................... -

EL CONSEJO DISTRITAL No. XXXVII TLALNEPANTLA

1/22 EL CONSEJO DISTRITAL No. XXXVII TLALNEPANTLA De conformidad con el “Convenio General de Coordinación entre el Instituto Nacional Electoral y el Instituto Electoral del Estado de México, para el desarrollo de las elecciones federal y local en la entidad”, Cláusula Sexta, Apartado A, Fracción II, Numeral 2.5., así como al Anexo Técnico del Convenio General de Coordinación entre el Instituto Nacional Electoral y el Instituto Electoral del Estado de México para el desarrollo de las elecciones federal y local en Estado de México, Clausula Segunda, Apartado A, Numeral 2.7., Inciso I). Domicilio del Consejo Distrital Electoral: Calle Nogal N° 28, Col. San Rafael, Tlalnepantla de Baz, Edo. de México, C.P. 54120, entre Av. Los Pinos y Nogal. Domicilio del Consejo Municipal Electoral de Tlalnepantla: Av. Atlacomulco No.52, Mza. 5, Col. Tlalnemex, Tlalnepantla, Edo. de México. C.P. 54070, entre Ixtlahuaca y Acolman. Tel: (55) 55 65 23 27, 53 84 09 85. FUNCIONARIOS PROPIETARIOS FUNCIONARIOS SUPLENTES GENERALES FUNCIONARIOS PROPIETARIOS FUNCIONARIOS SUPLENTES GENERALES DISTRITO: XXXVII TLALNEPANTLA SECCIÓN: 4758 CASILLA: CONTIGUA 2 UBICACIÓN: CASA DEL SEÑOR JOSE GUADALUPE MARIN SOTO , CLUB ALPINO TOLLATZINGO MANZANA 314 LOTE 3009, COLONIA LAZARO CARDENAS, TLALNEPANTLA DE BAZ, CODIGO POSTAL 54189, ENTRE MUNICIPIO: 105 TLALNEPANTLA DE BAZ PRESIDENTE CISNEROS CADENA ISAAC DIAZ AVILA NOEMI SECRETARIO 1 CAMPOS LOPEZ ARNULFO AVILA BARRIOS GREGORIA GUADALUPE SECCIÓN: 4757 CASILLA: BASICA SECRETARIO 2 CAZAREZ ORTIZ JUANA ANGUIANO MARTINEZ MARTHA UBICACIÓN: