How Solitary Are White Sharks: Social Interactions Or Just Spatial Proximity?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shark Mitigation and Deterrent Measures Submission 64

The Efficacy and Regulation of Shark Mitigation and Deterrent Measures Submission to: Senate Environment and Communications References Committee by Peter Stephenson BSc., ADAS 2815.3, Master Class V February 2017 As a commercial diver and fisherman with over 35 years of diverse experience I write this submission due to my ever-increasing concerns about policies governing management of and research into shark populations. I began snorkelling at the age of 7 and was a keen spear fisherman and surfer for decades although I am currently no longer active in these sports. (partly due to increasing negative shark incidents) I have a BSc. In marine science from Flinders University and have completed a number of years of marine research. Over more than four decades I have spent tens of thousands of hours observing and studying the marine environment. In recent years, particularly after my friends Peter Clarkson and Greg Pickering were attacked by white sharks, I have been researching shark attacks, shark behaviour and the possible factors influencing negative shark/ human interactions. I have also witnessed aggressive shark behaviour first hand but have luckily escaped serious injury…. so far. I currently work as an abalone diver in the South Australian Central Zone Abalone Fishery. THIS IS A MAJOR WORKPLACE SAFETY ISSUE FOR ME! THE BAITING AND HARASSMENT OF SHARKS FOR TOURISM AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH Despite legislation deeming the berleying, baiting, approach and harassment of white sharks illegal, governments grant exemptions and licences to tourism operators and scientists to conduct these activities. Despite years of research and observation, the level of conditioning of sharks by repeated berleying and baiting is still poorly understood and documented. -

The Great White Shark Quick Questions

The Great White Shark Quick Questions 11 Great white sharks are the top of the ocean’s food chain. 1. Why do you think that the great white shark is at 22 They are the biggest fish on our planet which eat other the top of the ocean’s food chain? 32 fish and animals. They are known to live between thirty 45 and one hundred years old and can be found in all of the 55 world’s oceans, but they are mostly found in cool water 59 close to the coast. 2. Where are most great white sharks found? 69 Even though they are mostly grey, they get their name 78 from their white underbelly. The great white shark has 89 been known to grow up to six metres long and have 99 up to three hundred sharp teeth, in seven rows. Their 3. Find and copy the adjective that the author uses 109 amazing sense of smell allows them to hunt for prey, to describe the shark’s sense of smell. 119 such as seals, rays and small whales from miles away. 4. Number these facts from 1 to 3 to show the order they appear in the text. They live between thirty and one hundred years. They can grow up to six metres long. They have up to three hundred teeth. The Great White Shark Answers 11 Great white sharks are the top of the ocean’s food chain. 1. Why do you think that the great white shark is at 22 They are the biggest fish on our planet which eat other the top of the ocean’s food chain? 32 fish and animals. -

Great White Shark) on Appendix I of the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

Prop. 11.48 Proposal to include Carcharodon carcharias (Great White Shark) on Appendix I of the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) A. PROPOSAL ..............................................................................................3 B. PROPONENT............................................................................................3 C. SUPPORTING STATEMENT....................................................................3 1. Taxonomy.........................................................................................................................3 1.1 Class.................................................................................................................................... 1.2 Order................................................................................................................................... 1.3 Family ................................................................................................................................. 1.4 Species ................................................................................................................................ 1.5 Scientific Synonyms............................................................................................................. 1.6 Common Names .................................................................................................................. 2. Biological Parameters......................................................................................................3 -

8Th MEETING of the SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE New Zealand, 3 to 8 October 2020

th 8 MEETING OF THE SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE New Zealand, 3 to 8 October 2020 SC8-DW14 Interactions with marine mammals, seabirds, reptiles, other species of concern New Zealand PO Box 3797, Wellington 6140, New Zealand P: +64 4 499 9889 – F: +64 4 473 9579 – E: [email protected] www.sprfmo.int SC8-DW14 South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organisation 8th Meeting of the Scientific Committee Online meeting hosted by New Zealand, 3–8 October 2020 Interactions with marine mammals, seabirds, reptiles (turtles), and other species of concern in bottom fisheries to 2019 Martin Cryer1, Igor Debski2, Shane W. Geange2, Tiffany D. Bock3, Marco Milardi3 3 September 2020 1. Fisheries New Zealand, Ministry for Primary Industries, Nelson, New Zealand 2. Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand 3. Fisheries New Zealand, Ministry for Primary Industries, Wellington, New Zealand 1 SC8-DW14 Contents 1. Purpose of paper ............................................................................................................. 3 2. Requirements of CMM-03-2020 and CMM-02-2020 ....................................................... 3 3. Reported interactions ..................................................................................................... 3 4. Discussion of seabird interactions ................................................................................... 5 5. Processes for verifying records and updating databases ................................................. 6 6. Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................... -

Three from One = 4000 Magazi

www.mcdoa.org.uk N A V AS MAGAzi totzsin Three from One = 4000 iiiiiiimmommhill111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111101111111111111111111miniiiimnum 11 •_„,,• Siebe Gorman present a now air compressor and cylinder charging decanting set, with an integrated control panel, which can be used for three distinct operations:— To charge large high pressure air storage cylinders to 40001b./sq.in. To decant air from storage cylinders into breathing apparatus or aqualung cylinders. To charge breathing apparatus cylin- ders direct from the compressor. filter and,control panel is mounted In a tubujik.Steel carrying frame and Neptune 4000 weighs-aiiiiroximately 400 lb. It can be Siebe Gorman's new high pressure used independently or incorporated compressor set is designed to provide in a static installation. a versatile unit for charging breathing apparatus or aqualung cylinders with clean, dry air to pressures between ;14,44, 1800 and 4000 p.s.i. Driven by either a `1AN Marineland—see page 9 Ut`, 4 stroke petrol engine or electric 01 ENGLAND -t motor, the air-cooled compressor has For further information, nii, write to 111111111111111141111 1111„i an output of 4.5 cu. ft. of nominal free Siebe Gorman & Co. Ltd., """"""1111111111IM11111111111111111111111 iiiiiiiiiimilimill111191111111111111111111111111111111111111111411 „1040 Neptune Works, Davis Road, F 0,40 air per minute. The complete appara- Chessington, Surrey. -.0.4640 tus, consisting of motor, compressor, Telephone: Lower Hook 8171/8 Printed by Coasby & Co. Ltd., St. James's Road, Southsea, Hai is www.mcdoa.org.uk Vol. 11 No. 1 2/- www.mcdoa.org.uk We specialise in EVERYTHING FOR THE UNDERWATER SPORTSMAN including the latest designs and all the better makes of LUNGS DIVING SUITS SWIMMING GEAR & EQUIPMENT Stainless steel Roles- Oyster, f37. -

Dives of the Bathyscaph Trieste, 1958-1963: Transcriptions of Sixty-One Dictabelt Recordings in the Robert Sinclair Dietz Papers, 1905-1994

Dives of the Bathyscaph Trieste, 1958-1963: Transcriptions of sixty-one dictabelt recordings in the Robert Sinclair Dietz Papers, 1905-1994 from Manuscript Collection MC28 Archives of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography University of California, San Diego La Jolla, California 92093-0219: September 2000 This transcription was made possible with support from the U.S. Naval Undersea Museum 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................4 CASSETTE TAPE 1 (Dietz Dictabelts #1-5) .................................................................................6 #1-5: The Big Dive to 37,800. Piccard dictating, n.d. CASSETTE TAPE 2 (Dietz Dictabelts #6-10) ..............................................................................21 #6: Comments on the Big Dive by Dr. R. Dietz to complete Piccard's description, n.d. #7: On Big Dive, J.P. #2, 4 Mar., n.d. #8: Dive to 37,000 ft., #1, 14 Jan 60 #9-10: Tape just before Big Dive from NGD first part has pieces from Rex and Drew, Jan. 1960 CASSETTE TAPE 3 (Dietz Dictabelts #11-14) ............................................................................30 #11-14: Dietz, n.d. CASSETTE TAPE 4 (Dietz Dictabelts #15-18) ............................................................................39 #15-16: Dive #61 J. Piccard and Dr. A. Rechnitzer, depth of 18,000 ft., Piccard dictating, n.d. #17-18: Dive #64, 24,000 ft., Piccard, n.d. CASSETTE TAPE 5 (Dietz Dictabelts #19-22) ............................................................................48 #19-20: Dive Log, n.d. #21: Dr. Dietz on the bathysonde, n.d. #22: from J. Piccard, 14 July 1960 CASSETTE TAPE 6 (Dietz Dictabelts #23-25) ............................................................................57 #23-25: Italian Dive, Dietz, Mar 8, n.d. CASSETTE TAPE 7 (Dietz Dictabelts #26-29) ............................................................................64 #26-28: Italian Dive, Dietz, n.d. -

Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997

The IUCN Species Survival Commission Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997 Edited by Sarah L. Fowler, Tim M. Reed and Frances A. Dipper Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 25 IUCN The World Conservation Union Donors to the SSC Conservation Communications Programme and Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management: Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997 The IUCN/Species Survival Commission is committed to communicate important species conservation information to natural resource managers, decision-makers and others whose actions affect the conservation of biodiversity. The SSC's Action Plans, Occasional Papers, newsletter Species and other publications are supported by a wide variety of generous donors including: The Sultanate of Oman established the Peter Scott IUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund in 1990. The Fund supports Action Plan development and implementation. To date, more than 80 grants have been made from the Fund to SSC Specialist Groups. The SSC is grateful to the Sultanate of Oman for its confidence in and support for species conservation worldwide. The Council of Agriculture (COA), Taiwan has awarded major grants to the SSC's Wildlife Trade Programme and Conservation Communications Programme. This support has enabled SSC to continue its valuable technical advisory service to the Parties to CITES as well as to the larger global conservation community. Among other responsibilities, the COA is in charge of matters concerning the designation and management of nature reserves, conservation of wildlife and their habitats, conservation of natural landscapes, coordination of law enforcement efforts as well as promotion of conservation education, research and international cooperation. -

080058-89.02.017.Pdf

t9l .Ig6I pup spu?Fr rr"rl?r1mv qnos raq1oaqt dq panqs tou pus 916I uao^\teq sluauennboJ puu surelqord lusue8suuur 1eneds wq sauo8a uc .fu1mpw snorru,r aql uI luar&(oldua ',uq .(tg6l a;oJareqt puuls1oore8ueltr 0t dpo 1u reted lS sr ur saiuzqc aql s,roqs osIB elqeJ srqt usrmoJ 'urpilsny 'V'S) puels tseSrul geu oq; ur 1sa?re1p4ql aql 3o luetugedeq Z alq?J rrr rtr\oqs su padoldua puu prr"lsr aroqsJJorrprJpnsnv qlnos lsJErel aql ruJ ere,u eldoed ZS9 I feqf pa roqs snsseC srllsll?ls dq r ?olp sp qlr^\ puplsl oorp8ue1 Jo neomg u"rl?Jlsnv eql uo{ sorn8g luereJ lsour ,u1 0g€ t Jo eW T86I ul puu 00S € ,{lel?urxorddu sr uoqelndod '(derd ur '8ur,no:8 7r luosaJd eqJ petec pue uoqcnpord ,a uosurqoU) uoqecrJqndro3 peredard Smeq ,{11uermc '(tg6l )potsa^q roJ perualo Suraq puel$ oql Jo qJnu eru sda,r-rnsaseql3o EFSer pa[elop aqJ &usJ qlvrr pedolaaap fuouoce Surqsg puu Surure; e puu pue uosurqo;) pegoder useq aleq pesn spoporu palles-er su,rr prrqsr eql sreo,{ Eurpeet:ns eq1 re,ro prru s{nser druuruqord aqt pue (puep1 ooreSuqtr rnq 698I uI peuopwqs sE^\ elrs lrrrod seaeell eql SumnJcxa) sprrelsl aroqsJJo u"{e4snv qlnos '998I raqueJeo IIl eprelepv Jo tuaruslDesIeuroJ oqt aql Jo lsou uo palelduor ueeq A\ou aaeq s,{e,rrns aro3aq ,(ueduo3 rr"4u4snv qtnos qtgf 'oAE eqt dq ,{nt p:6o1org sree,{009 6 ol 000 L uea r1aq palulosr ur slors8rry1 u,no1paserd 6rll J?eu salaed 'o?e ;o lrrrod ererrirspuulsr Surura sr 3ql Jo dllJolpu aq; sree,{ paqslqplse peuuurad lE s?a\lueurep1os uuedorng y 009 0I spuplsl dpearg pue uosr"ed pup o8e srea,{ 'seruolocuorJ-"3s rel?l puB -

S P E N C E R G U L F S T G U L F V I N C E N T Adelaide

Yatala Harbour Paratoo Hill Turkey 1640 Sunset Hill Pekina Hill Mt Grainger Nackara Hill 1296 Katunga Booleroo "Avonlea" 2297 Depot Hill Creek 2133 Wilcherry Hill 975 Roopena 1844 Grampus Hill Anabama East Hut 1001 Dawson 1182 660 Mt Remarkable SOUTH Mount 2169 440 660 (salt) Mt Robert Grainger Scobie Hill "Mazar" vermin 3160 2264 "Manunda" Wirrigenda Hill Weednanna Hill Mt Whyalla Melrose Black Rock Goldfield 827 "Buckleboo" 893 729 Mambray Creek 2133 "Wyoming" salt (2658±) RANGE Pekina Wheal Bassett Mine 1001 765 Station Hill Creek Manunda 1073 proof 1477 Cooyerdoo Hill Maurice Hill 2566 Morowie Hill Nackara (abandoned) "Bulyninnie" "Oak Park" "Kimberley" "Wilcherry" LAKE "Budgeree" fence GILLES Booleroo Oratan Rock 417 Yeltanna Hill Centre Oodla "Hill Grange" Plain 1431 "Gilles Downs" Wirra Hillgrange 1073 B pipeline "Wattle Grove" O Tcharkuldu Hill T Fullerville "Tiverton 942 E HWY Outstation" N Backy Pt "Old Manunda" 276 E pumping station L substation Tregalana Baroota Yatina L Fitzgerald Bay A Middleback Murray Town 2097 water Ucolta "Pitcairn" E Buckleboo 1306 G 315 water AN Wild Dog Hill salt Tarcowie R Iron Peak "Terrananya" Cunyarie Moseley Nobs "Middleback" 1900 works (1900±) 1234 "Lilydale" H False Bay substation Yaninee I Stoney Hill O L PETERBOROUGH "Blue Hills" LC L HWY Point Lowly PEKINA A 378 S Iron Prince Mine Black Pt Lancelot RANGE (2294±) 1228 PU 499 Corrobinnie Hill 965 Iron Baron "Oakvale" Wudinna Hill 689 Cortlinye "Kimboo" Iron Baron Waite Hill "Loch Lilly" 857 "Pualco" pipeline Mt Nadjuri 499 Pinbong 1244 Iron -

Great White Shark Carcharodon Carcharias

Great White Shark Carcharodon carcharias Great White Sharks (Great Whites) are large predators at the top of the marine food chain. They are in the same class as all sharks and rays (Chondrichthyes) – this group is different from other fish as their skeleton is made from cartilage instead of bone. They have an average length of four to five metres, but can grow up to seven metres. Using their powerful tails to propel them, these sharks can move Bioregion resources through the water at up to 24 km per hour. Their mouths are lined with up to 300 serrated triangular teeth arranged in several rows. Diet Great Whites are able to use electroreception (the ability to detect weak electrical currents) to find and attack prey without seeing it. This can be useful in murky water or when their prey is hidden under sediment. This gives them the ability to navigate by sensing the Earth’s magnetic field. They have a strong sense of smell which is also useful in detecting prey. Contrary to some people’s beliefs, they often only attack humans to ‘sample bite’ and do not usually choose to eat human flesh, preferring marine mammals such as seals and sea lions. They are also known to feed on dolphins, octopus, squid, other sharks, rays and lobster, fish, crabs and seabirds. Breeding Great Whites have a low reproduction rate that makes it difficult for species numbers to recover. Males mature at eight to ten years and females mature at 12-18 years. Females give birth to two to ten pups once every two to three years. -

Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks Great White Shark Fact Sheet

CMS/MOS3/Inf.15b Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation of Migratory Sharks Great White Shark Fact Sheet Class: Chondrichthyes Great White shark Grand requin blanc Order: Lamniformes Jaquetón blanco Family: Lamnidae Species: Carcharodon carcharias Illustration: © Marc Dando 1. BIOLOGY Carcharodon carcharias (Great white shark) inhabit coastal waters of subtropical and temperate seas. Female age at maturity is uncertain ranging between 9 and 17 years (Smith et al. 1998, Mollet and Cailliet (2002). Reported litter size ranges between 2- 17 pups per female (Bruce, 2008). Von Bertalanffy growth estimates of white shark range from a k value=0.159 y−1 for female sharks from Japan whereas Cailliet et al. (1985) and Wintner and Cliff (1999) reported k values of 0.058 y−1 and 0.065 y−1 (sexes combined) for individuals collected in California and South Africa, respectively. Based on bomb radio-carbon signatures, the maximum age of white sharks is up to 73 years (Hamady et al., 2014). 2. DISTRIBUTION The white shark is distributed throughout all oceans, with concentrations in temperate coastal areas (Compagno 2001), including inter alia California, USA to Baja California, Mexico (Ainley et al. 1985, Klimley 1985, Domeier and Nasby-Lucas 2007, Lowe et al. 2012, Onate-Gonzalez et al. 2017), North West Atlantic (Casey and Pratt 1985, Curtis et al. 2014), Australia (Bruce 1992, Bruce and Bradford 2012, McAuley et al. 2017), and South Africa (Ferreira & Ferreira 1996, Dudley 2012). The Mediterranean Sea is thought to host a fairly isolated population with little or no contemporary immigration from the Atlantic (Gubili et al. -

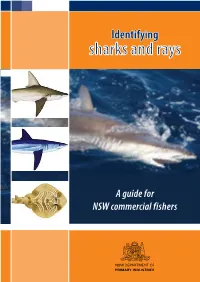

Identifying Sharks and Rays

NSW DPI Identifying sharks and rays A guide for NSW commercial fishers Important If a shark or ray cannot be confidently identified using this guide, it is recommended that either digital images are obtained or the specimen is preserved. Please contact NSW DPI research staff for assistance: phone 1300 550 474 or email [email protected] Contents Introduction 4 How to use this guide 5 Glossary 6-7 Key 1 Whaler sharks and other sharks of similar appearance 8-9 to whalers – upper precaudal pit present Key 2 Sharks of similar appearance to whaler sharks – no 10 precaudal pit Key 3 Mackerel (great white and mako), hammerhead and 11 thresher sharks Key 4 Wobbegongs and some other patterned 12 bottom-dwelling sharks Key 5 Sawsharks and other long-snouted sharks and rays 13 2 Sandbar shark 14 Great white shark 42 Bignose shark 15 Porbeagle 43 Dusky whaler 16 Shortfin mako 44 Silky shark 17 Longfin mako 45 Oceanic whitetip shark 18 Thresher shark 46 Tiger shark 19 Pelagic thresher 47 Common blacktip shark 20 Bigeye thresher 48 Spinner shark 21 Great hammerhead 49 Blue shark 22 Scalloped hammerhead 50 Sliteye shark 23 Smooth hammerhead 51 Bull shark 24 Eastern angelshark 52 Bronze whaler 25 Australian angelshark 53 Weasel shark 26 Banded wobbegong 54 Lemon shark 27 Ornate wobbegong 55 Grey nurse shark 28 Spotted wobbegong 56 Sandtiger (Herbst’s nurse) shark 29 Draughtboard shark 57 Bluntnose sixgill shark 30 Saddled swellshark 58 Bigeye sixgill shark 31 Whitefin swellshark 59 Broadnose shark 32 Port Jackson shark 60 Sharpnose sevengill