Where Next? Football's New Frontiers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theory of the Beautiful Game: the Unification of European Football

Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 54, No. 3, July 2007 r 2007 The Author Journal compilation r 2007 Scottish Economic Society. Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main St, Malden, MA, 02148, USA THEORY OF THE BEAUTIFUL GAME: THE UNIFICATION OF EUROPEAN FOOTBALL John Vroomann Abstract European football is in a spiral of intra-league and inter-league polarization of talent and wealth. The invariance proposition is revisited with adaptations for win- maximizing sportsman owners facing an uncertain Champions League prize. Sportsman and champion effects have driven European football clubs to the edge of insolvency and polarized competition throughout Europe. Revenue revolutions and financial crises of the Big Five leagues are examined and estimates of competitive balance are compared. The European Super League completes the open-market solution after Bosman. A 30-team Super League is proposed based on the National Football League. In football everything is complicated by the presence of the opposite team. FSartre I Introduction The beauty of the world’s game of football lies in the dynamic balance of symbiotic competition. Since the English Premier League (EPL) broke away from the Football League in 1992, the EPL has effectively lost its competitive balance. The rebellion of the EPL coincided with a deeper media revolution as digital and pay-per-view technologies were delivered by satellite platform into the commercial television vacuum created by public television monopolies throughout Europe. EPL broadcast revenues have exploded 40-fold from h22 million in 1992 to h862 million in 2005 (33% CAGR). -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

2017-18 Panini Nobility Soccer Cards Checklist

Cardset # Player Team Seq # Player Team Note Crescent Signatures 28 Abby Wambach United States Alessandro Del Piero Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 28 Abby Wambach United States 49 Alessandro Nesta Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 28 Abby Wambach United States 20 Andriy Shevchenko Ukraine DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 28 Abby Wambach United States 10 Brad Friedel United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 28 Abby Wambach United States 1 Carles Puyol Spain DEBUT Crescent Signatures 16 Alan Shearer England Carlos Gamarra Paraguay DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 16 Alan Shearer England 49 Claudio Reyna United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 16 Alan Shearer England 20 Eric Cantona France DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 16 Alan Shearer England 10 Freddie Ljungberg Sweden DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 16 Alan Shearer England 1 Gabriel Batistuta Argentina DEBUT Iconic Signatures 27 Alan Shearer England 35 Gary Neville England DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 27 Alan Shearer England 20 Karl-Heinz Rummenigge Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 27 Alan Shearer England 10 Marc Overmars Netherlands DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 27 Alan Shearer England 1 Mauro Tassotti Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures 35 Aldo Serena Italy 175 Mehmet Scholl Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 35 Aldo Serena Italy 20 Paolo Maldini Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 35 Aldo Serena Italy 10 Patrick Vieira France DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 35 Aldo Serena Italy 1 Paul Scholes England DEBUT Crescent Signatures 12 Aleksandr Mostovoi -

Goal Celebrations When the Players Makes the Show

Goal celebrations When the players makes the show Diego Maradona rushing the camera with the face of a madman, José Mourinho performing an endless slide on his knees, Roger Milla dancing with the corner flag, three Brazilians cradling an imaginary baby, Robbie Fowler sniffing the white line, Cantona, a finger to his lips contemplating his incredible talent... Discover the most fantastic ways to celebrate a goal. Funny, provo- cative, pretentious, imaginative, catch football players in every condition. KEY SELLING POINTS • An offbeat treatment of football • A release date during the Euro 2016 • Surprising and entertaining • A well-known author on the subject • An attractive price THE AUTHOR Mathieu Le Maux Mathieu Le Maux is head sports writer at GQ magazine. He regularly contributes to BeInSport. His key discipline is football. SPECIFICATIONS Format 150 x 190 mm or 170 x 212 mm Number of pages 176 pp Approx. 18,000 words Price 15/20 € Release spring 2016 All rights available except for France 104 boulevard arago | 75014 paris | france | contact nicolas marçais | +33 1 44 16 92 03 | [email protected] | copyrighteditions.com contENTS The Hall of Fame Goal celebrations from the football legends of the past to the great stars of the moment: Pele, Eric Cantona, Diego Maradona, George Best, Eusebio, Johan Cruijff, Michel Platini, David Beckham, Zinedine Zidane, Didier Drogba, Ronaldo, Messi, Thierry Henry, Ronaldinho, Cristiano Ronaldo, Balotelli, Zlatan, Neymar, Yekini, Paul Gascoigne, Roger Milla, Tardelli... Total Freaks The wildest, craziest, most unusual, most spectacular goal celebrations: Robbie Fowler, Maradona/Caniggia, Neville/Scholes, Totti selfie, Cavani, Lucarelli, the team of Senegal, Adebayor, Rooney Craig Bellamy, the staging of Icelanders FC Stjarnan, the stupid injuries of Paolo Diogo, Martin Palermo or Denilson.. -

Euro-Sportring/L&J Group, Inc. 13710 E. Rice Place-Suite 110, Aurora, CO 80015 Telephone: (303) 768-0891, Toll Free: (800) 7

Euro-Sportring/L&J Group, Inc. 13710 E. Rice Place-Suite 110, Aurora, CO 80015 Telephone: (303) 768-0891, Toll free: (800) 724-6076, Telefax: (303) 768-0756, E-Mail: [email protected] Introduction Soccer fans around the world admire the Dutch style of play. Players like Johan Cruyff, Ruud Gullit, Marco van Basten and Dennis Bergkamp, and more recently Ruud van Nistelrooy, Arjen Robben and Robin van Persie, have long set a standard for exciting, creative play. In the 1980's and '90's The Netherlands provided the soccer world with entertaining teams and players. Recent Dutch soccer success includes semifinal appearances at the 1998 World Cup and Euro 2000 and 2004, a quarter final appearance in the 2008 European Championships, as well as reaching the Round of 16 at the 2006 World Cup, and the Dutch national team is usually always in the top 10 in the FIFA World Rankings. The on-field success of Dutch soccer is mirrored by the world-renowned KNVB coaching Academy. At its foundation stands Rinus Michels, the man who "invented" Total Soccer in the '70s. His ideas are the basis of this camp. Small Nation, Great soccer vision The Netherlands is small in size, but Dutch soccer is famous around the world. For the past 30 years the Dutch have played a vital role in international soccer. The national team has recorded astonishing successes in the European Championship and World Cups. The top Dutch soccer clubs have shown well in every major European Cup competition, while Dutch players have long filled the rosters of the most popular European clubs. -

Negrocity: an Interview with Greg Tate

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2012 Negrocity: An Interview with Greg Tate Camille Goodison CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/731 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] NEGROCITY An Interview with Greg Tate* by Camille Goodison As a cultural critic and founder of Burnt Sugar The Arkestra Chamber, Greg Tate has published his writings on art and culture in the New York Times, Village Voice, Rolling Stone, and Jazz Times. All Ya Needs That Negrocity is Burnt Sugar's twelfth album since their debut in 1999. Tate shared his thoughts on jazz, afro-futurism, and James Brown. GOODISON: Tell me about your life before you came to New York. TATE: I was born in Dayton, Ohio, and we moved to DC when I was about twelve, so that would have been about 1971, 1972, and that was about the same time I really got interested in music, collecting music, really interested in collecting jazz and rock, and reading music criticism too. It kinda all happened at the same time. I had a subscription to Rolling Stone. I was really into Miles Davis. He was like my god in the 1970s. Miles, George Clinton, Sun Ra, and locally we had a serious kind of band scene going on. -

Street Soccer

STREET SOCCER Street soccer, pick-up game, sandlot soccer or a kick-about whatever title you give to the format the idea is to give the game of soccer back to the players. Past generations learned to play the game on their own with other kids in the neighborhood or at school in these kid organized games. Today youth sports are overly adult controlled and influenced. It’s difficult today for youngsters to have a pick-up game since the streets have too many cars, the sandlot now has a mini- mall on it and parents are reluctant, with good cause, to let their child go blocks away from home on Saturday to play in a game on his or her own. Street soccer is a way for soccer clubs to give the game back to the players in the community. Once a week, or whatever frequency fits the circumstances the best, a club can have organized spontaneity. The club will provide the fields and supervision. Adults will be on site for safety and general supervision, but otherwise it is all up to the players to organize the games. The adults should NOT coach, cheer, criticize, referee or in any other way involve themselves in the game. The best bet for parents is to drop off their child, go run some errands, and then come back to pick up your child an hour or two latter. The coaches are on site NOT to coach, but to supervise, be on hand for any serious injuries and any severe discipline problems. Additionally the coaches are there to provide the game equipment and to let the players know when each game segment starts and stops. -

No. 143 | November 2014 in This Issue

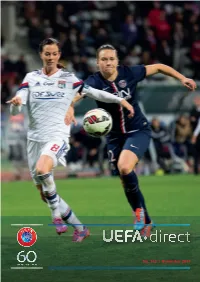

No. 143 | November 2014 IN THIS ISSUE Official publication of the SECOND WOMEN IN FOOTBALL Union of European Football Associations LEADERSHIP SEMINAR 4 Images The second week-long Women in Football Leadership seminar Getty took place at the House of European Football in Nyon at the end via Chief editor: of October. Emmanuel Deconche UEFA Produced by: PAO graphique, CH-1110 Morges SOLIDARY PAYMENTS TO CLUBS Printing: 10 Artgraphic Cavin SA, A share of the revenue earned by the UEFA Champions League CH-1422 Grandson goes to the clubs involved in the UEFA Champions League and Editorial deadline: UEFA Europa League qualifying rounds. This season, 183 clubs Images 8 November 2014 have benefitted. Getty The views expressed in signed articles are not necessarily the official views of UEFA. HISTORIC AGREEMENT SIGNED The reproduction of articles IN BRUSSELS 13 published in UEFA·direct is authorised, provided the On 14 October the European Commission and UEFA Commission source is indicated. signed an agreement designed to reinforce relations between the two institutions. European POSITIVE FEEDBACK ON FINANCIAL FAIR PLAY 14 Two important financial fair play events were organised in the past two months: in September a UEFA club licensing and financial fair play workshop took place in Dublin, followed Sportsfile Cover: in October by a round table in Nyon. Lotta Schelin of Olympique Lyonnais gets in front of Joséphine Henning of Paris Saint-Germain in the first NEWS FROM MEMBER ASSOCIATIONS 15 leg of their UEFA Women’s Champions League round of 16 tie (1-1) technician No. 57 | November 2014 SUPPLEMENT EDITORIAL THE SHARING OF KNOWLEDGE Photo: E. -

KNVB Camp Flyer 2012

KNVB Soccer Camp Team Elmhurst Soccer Club // July 16-20, 2012 Team Elmhurst Soccer Club and Premier International Tours/L&J Group have arranged to fly in a top coach(es) player in FIFA's "Team of the Year 2000" went through the from the Dutch Soccer Federation (KNVB) to execute a Dutch program, and all were educated the same winning soccer camp for players specifically from our club. The way: Edgar Davids, Patrick Kluivert, Marc Overmars, camp will take place July 16-20, 2012 at Berens Park. Clarence Seedorf and Dennis Bergkamp. They follow in the footsteps of the greatest stars from the legendary Euro '88- Soccer fans around winning team: Marco van Basten, Ruud Gullit, Frank Rijkaard the world admire the and Ronald Koeman. Dutch style of play. Players like Johan We provide one KNVB coach for each team/group of 15-18 Cruyff, Ruud Gullit, players. Next to the Dutch staff, each team/group will have Marco van Basten, its own coaching staff as well. Dennis Bergkamp, Wesley Sneijder and Sample Daily Program (3.5 hours per day): Rafael van der Vart, Morning Session: 4v4, 7v7, 9v9 – small sided games, have long set a special instructions. 2 hours in the morning standard for exciting, Afternoon Session: Training in small groups on transition creative play. In the from possession of ball. 1.5 hours in the afternoon. 1980's and '90's The U10-U11 players – 8:00-10:00 AM and 2:00-3:30 PM Netherlands provided U12-U14 players – 10:00-12:00 noon and 3:30-5:00 PM the soccer world with entertaining teams and players. -

Multiple Documents

Alex Morgan et al v. United States Soccer Federation, Inc., Docket No. 2_19-cv-01717 (C.D. Cal. Mar 08, 2019), Court Docket Multiple Documents Part Description 1 3 pages 2 Memorandum Defendant's Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of i 3 Exhibit Defendant's Statement of Uncontroverted Facts and Conclusions of La 4 Declaration Gulati Declaration 5 Exhibit 1 to Gulati Declaration - Britanica World Cup 6 Exhibit 2 - to Gulati Declaration - 2010 MWC Television Audience Report 7 Exhibit 3 to Gulati Declaration - 2014 MWC Television Audience Report Alex Morgan et al v. United States Soccer Federation, Inc., Docket No. 2_19-cv-01717 (C.D. Cal. Mar 08, 2019), Court Docket 8 Exhibit 4 to Gulati Declaration - 2018 MWC Television Audience Report 9 Exhibit 5 to Gulati Declaration - 2011 WWC TElevision Audience Report 10 Exhibit 6 to Gulati Declaration - 2015 WWC Television Audience Report 11 Exhibit 7 to Gulati Declaration - 2019 WWC Television Audience Report 12 Exhibit 8 to Gulati Declaration - 2010 Prize Money Memorandum 13 Exhibit 9 to Gulati Declaration - 2011 Prize Money Memorandum 14 Exhibit 10 to Gulati Declaration - 2014 Prize Money Memorandum 15 Exhibit 11 to Gulati Declaration - 2015 Prize Money Memorandum 16 Exhibit 12 to Gulati Declaration - 2019 Prize Money Memorandum 17 Exhibit 13 to Gulati Declaration - 3-19-13 MOU 18 Exhibit 14 to Gulati Declaration - 11-1-12 WNTPA Proposal 19 Exhibit 15 to Gulati Declaration - 12-4-12 Gleason Email Financial Proposal 20 Exhibit 15a to Gulati Declaration - 12-3-12 USSF Proposed financial Terms 21 Exhibit 16 to Gulati Declaration - Gleason 2005-2011 Revenue 22 Declaration Tom King Declaration 23 Exhibit 1 to King Declaration - Men's CBA 24 Exhibit 2 to King Declaration - Stolzenbach to Levinstein Email 25 Exhibit 3 to King Declaration - 2005 WNT CBA Alex Morgan et al v. -

Zinedine Zidane Voted Top Player by Fans

Media Release Date: 22/04/2004 Communiqué aux médias No. 063 Medien-Mitteilung Zinedine Zidane voted top player by fans uefa.com users vote Zidane, Beckenbauer and Cruyff as top three The search to find European football's top player from the past 50 years ended today, Thursday 22 April, with the announcement that French international midfielder Zinedine Zidane has beaten off competition from German great Franz Beckenbauer and Dutch master Johan Cruyff, to be named number one by the users of uefa.com. The announcement, made at the UEFA Golden Jubilee ceremony, which opened the XXVIII Ordinary UEFA Congress in Limassol, provided much discussion among the assembled delegates and football representatives, especially with Beckenbauer in attendance. "Just to be in the top 20 is touching, it's great," said Zidane, who provided a message via video from the Spanish capital. "It is extraordinary to be voted one of the best European players of the past 50 years. I am a bit surprised, but I am very glad that people appreciate what we do on the pitch. “I am bracketed with those players that have made a difference in the last 50 years and when you play football, this is the reason you do it. For me, football is everything. It was my biggest passion and something I always knew how to do best. Even today, practically at the end of my career, I enjoy playing football. It is a privilege." No formal award was made to Zidane, although as part of the 50th anniversary celebrations of both UEFA and the Asian Football Confederation (AFC), UEFA will provide a donation to a Youth football development fund being administered by the AFC in order to help install an artificial turf pitch in East Timor, which will be named after the France and Real Madrid CF midfielder. -

Villa: “Lo He Pasado Muy Mal; Ahora Me Toca Disfrutar”

REVISTA DE LA RFEF ✦ AÑO XIV ✦ NÚMERO 116 ✦ ENERO 2009 ✦ 2,50 e REVISTA DE LA RFEF AÑO XVII - Nº 159 Octubre 2012 - 2,50 € Villa: “Lo he pasado muy mal; ahora me toca disfrutar” Espectacular Adriana y clasificación de la Vero celebran el primer gol absoluta femenina de España, marcado por y exhibición de la aquella. “sub 21” masculina, Foto: clasificados para Eidan Rubio. los Europeos. La selección lidera su grupo del Mundial 2014, tras golear a Bielorrusia y empatar con Francia. La alegría de España editorial En cabeza, pese a todo ESPAÑA HA CONCLUIDO el primer sprint de la fase de los mismos puntos, siete, que España, tras haber derrotado clasificación del Mundial 2014 a la cabeza de su grupo, a Finlandia, en Helsinki y a Bielorrusia, en París. igualada con Francia, que empató en el Vicente Calderón Las tablas frente a la tricolor no son el mejor resultado que en el último suspiro del duelo, pero líder por mayor diferen- podía darse, naturalmente, pero ni han dañado el crédito cia de goles. El 0-4 de Minsk (Bielorrusia) anterior, añadido de los campeones ni debe tomarse, ¡faltaría más!, como al 0-1 de Tbilisi (Georgia) y al 1-1 de Madrid ha hecho valer el despertar precipitado, tras un resultado corto, de tiem- dicha posición, situando al campeón de Europa y del mun- pos preocupantes. Hasta el pasado día 16, España lle- do al mando. vaba acumulados 24 triunfos en 24 partidos de fases de La selección ha finalizado con buena nota, por tanto, los clasificación, doce de ellos a domicilio.