Chapter 10: Gases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solutes and Solution

Solutes and Solution The first rule of solubility is “likes dissolve likes” Polar or ionic substances are soluble in polar solvents Non-polar substances are soluble in non- polar solvents Solutes and Solution There must be a reason why a substance is soluble in a solvent: either the solution process lowers the overall enthalpy of the system (Hrxn < 0) Or the solution process increases the overall entropy of the system (Srxn > 0) Entropy is a measure of the amount of disorder in a system—entropy must increase for any spontaneous change 1 Solutes and Solution The forces that drive the dissolution of a solute usually involve both enthalpy and entropy terms Hsoln < 0 for most species The creation of a solution takes a more ordered system (solid phase or pure liquid phase) and makes more disordered system (solute molecules are more randomly distributed throughout the solution) Saturation and Equilibrium If we have enough solute available, a solution can become saturated—the point when no more solute may be accepted into the solvent Saturation indicates an equilibrium between the pure solute and solvent and the solution solute + solvent solution KC 2 Saturation and Equilibrium solute + solvent solution KC The magnitude of KC indicates how soluble a solute is in that particular solvent If KC is large, the solute is very soluble If KC is small, the solute is only slightly soluble Saturation and Equilibrium Examples: + - NaCl(s) + H2O(l) Na (aq) + Cl (aq) KC = 37.3 A saturated solution of NaCl has a [Na+] = 6.11 M and [Cl-] = -

Sanitization: Concentration, Temperature, and Exposure Time

Sanitization: Concentration, Temperature, and Exposure Time Did you know? According to the CDC, contaminated equipment is one of the top five risk factors that contribute to foodborne illnesses. Food contact surfaces in your establishment must be cleaned and sanitized. This can be done either by heating an object to a high enough temperature to kill harmful micro-organisms or it can be treated with a chemical sanitizing compound. 1. Heat Sanitization: Allowing a food contact surface to be exposed to high heat for a designated period of time will sanitize the surface. An acceptable method of hot water sanitizing is by utilizing the three compartment sink. The final step of the wash, rinse, and sanitizing procedure is immersion of the object in water with a temperature of at least 170°F for no less than 30 seconds. The most common method of hot water sanitizing takes place in the final rinse cycle of dishwashing machines. Water temperature must be at least 180°F, but not greater than 200°F. At temperatures greater than 200°F, water vaporizes into steam before sanitization can occur. It is important to note that the surface temperature of the object being sanitized must be at 160°F for a long enough time to kill the bacteria. 2. Chemical Sanitization: Sanitizing is also achieved through the use of chemical compounds capable of destroying disease causing bacteria. Common sanitizers are chlorine (bleach), iodine, and quaternary ammonium. Chemical sanitizers have found widespread acceptance in the food service industry. These compounds are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and consequently require labeling with the word “Sanitizer.” The labeling should also include what concentration to use, data on minimum effective uses and warnings of possible health hazards. -

Page 1 of 6 This Is Henry's Law. It Says That at Equilibrium the Ratio of Dissolved NH3 to the Partial Pressure of NH3 Gas In

CHMY 361 HANDOUT#6 October 28, 2012 HOMEWORK #4 Key Was due Friday, Oct. 26 1. Using only data from Table A5, what is the boiling point of water deep in a mine that is so far below sea level that the atmospheric pressure is 1.17 atm? 0 ΔH vap = +44.02 kJ/mol H20(l) --> H2O(g) Q= PH2O /XH2O = K, at ⎛ P2 ⎞ ⎛ K 2 ⎞ ΔH vap ⎛ 1 1 ⎞ ln⎜ ⎟ = ln⎜ ⎟ − ⎜ − ⎟ equilibrium, i.e., the Vapor Pressure ⎝ P1 ⎠ ⎝ K1 ⎠ R ⎝ T2 T1 ⎠ for the pure liquid. ⎛1.17 ⎞ 44,020 ⎛ 1 1 ⎞ ln⎜ ⎟ = − ⎜ − ⎟ = 1 8.3145 ⎜ T 373 ⎟ ⎝ ⎠ ⎝ 2 ⎠ ⎡1.17⎤ − 8.3145ln 1 ⎢ 1 ⎥ 1 = ⎣ ⎦ + = .002651 T2 44,020 373 T2 = 377 2. From table A5, calculate the Henry’s Law constant (i.e., equilibrium constant) for dissolving of NH3(g) in water at 298 K and 340 K. It should have units of Matm-1;What would it be in atm per mole fraction, as in Table 5.1 at 298 K? o For NH3(g) ----> NH3(aq) ΔG = -26.5 - (-16.45) = -10.05 kJ/mol ΔG0 − [NH (aq)] K = e RT = 0.0173 = 3 This is Henry’s Law. It says that at equilibrium the ratio of dissolved P NH3 NH3 to the partial pressure of NH3 gas in contact with the liquid is a constant = 0.0173 (Henry’s Law Constant). This also says [NH3(aq)] =0.0173PNH3 or -1 PNH3 = 0.0173 [NH3(aq)] = 57.8 atm/M x [NH3(aq)] The latter form is like Table 5.1 except it has NH3 concentration in M instead of XNH3. -

THE SOLUBILITY of GASES in LIQUIDS Introductory Information C

THE SOLUBILITY OF GASES IN LIQUIDS Introductory Information C. L. Young, R. Battino, and H. L. Clever INTRODUCTION The Solubility Data Project aims to make a comprehensive search of the literature for data on the solubility of gases, liquids and solids in liquids. Data of suitable accuracy are compiled into data sheets set out in a uniform format. The data for each system are evaluated and where data of sufficient accuracy are available values are recommended and in some cases a smoothing equation is given to represent the variation of solubility with pressure and/or temperature. A text giving an evaluation and recommended values and the compiled data sheets are published on consecutive pages. The following paper by E. Wilhelm gives a rigorous thermodynamic treatment on the solubility of gases in liquids. DEFINITION OF GAS SOLUBILITY The distinction between vapor-liquid equilibria and the solubility of gases in liquids is arbitrary. It is generally accepted that the equilibrium set up at 300K between a typical gas such as argon and a liquid such as water is gas-liquid solubility whereas the equilibrium set up between hexane and cyclohexane at 350K is an example of vapor-liquid equilibrium. However, the distinction between gas-liquid solubility and vapor-liquid equilibrium is often not so clear. The equilibria set up between methane and propane above the critical temperature of methane and below the criti cal temperature of propane may be classed as vapor-liquid equilibrium or as gas-liquid solubility depending on the particular range of pressure considered and the particular worker concerned. -

Producing Nitrogen Via Pressure Swing Adsorption

Reactions and Separations Producing Nitrogen via Pressure Swing Adsorption Svetlana Ivanova Pressure swing adsorption (PSA) can be a Robert Lewis Air Products cost-effective method of onsite nitrogen generation for a wide range of purity and flow requirements. itrogen gas is a staple of the chemical industry. effective, and convenient for chemical processors. Multiple Because it is an inert gas, nitrogen is suitable for a nitrogen technologies and supply modes now exist to meet a Nwide range of applications covering various aspects range of specifications, including purity, usage pattern, por- of chemical manufacturing, processing, handling, and tability, footprint, and power consumption. Choosing among shipping. Due to its low reactivity, nitrogen is an excellent supply options can be a challenge. Onsite nitrogen genera- blanketing and purging gas that can be used to protect valu- tors, such as pressure swing adsorption (PSA) or membrane able products from harmful contaminants. It also enables the systems, can be more cost-effective than traditional cryo- safe storage and use of flammable compounds, and can help genic distillation or stored liquid nitrogen, particularly if an prevent combustible dust explosions. Nitrogen gas can be extremely high purity (e.g., 99.9999%) is not required. used to remove contaminants from process streams through methods such as stripping and sparging. Generating nitrogen gas Because of the widespread and growing use of nitrogen Industrial nitrogen gas can be produced by either in the chemical process industries (CPI), industrial gas com- cryogenic fractional distillation of liquefied air, or separa- panies have been continually improving methods of nitrogen tion of gaseous air using adsorption or permeation. -

Part Two Physical Processes in Oceanography

Part Two Physical Processes in Oceanography 8 8.1 Introduction Small-Scale Forty years ago, the detailed physical mechanisms re- Mixing Processes sponsible for the mixing of heat, salt, and other prop- erties in the ocean had hardly been considered. Using profiles obtained from water-bottle measurements, and J. S. Turner their variations in time and space, it was deduced that mixing must be taking place at rates much greater than could be accounted for by molecular diffusion. It was taken for granted that the ocean (because of its large scale) must be everywhere turbulent, and this was sup- ported by the observation that the major constituents are reasonably well mixed. It seemed a natural step to define eddy viscosities and eddy conductivities, or mix- ing coefficients, to relate the deduced fluxes of mo- mentum or heat (or salt) to the mean smoothed gra- dients of corresponding properties. Extensive tables of these mixing coefficients, KM for momentum, KH for heat, and Ks for salinity, and their variation with po- sition and other parameters, were published about that time [see, e.g., Sverdrup, Johnson, and Fleming (1942, p. 482)]. Much mathematical modeling of oceanic flows on various scales was (and still is) based on simple assumptions about the eddy viscosity, which is often taken to have a constant value, chosen to give the best agreement with the observations. This approach to the theory is well summarized in Proudman (1953), and more recent extensions of the method are described in the conference proceedings edited by Nihoul 1975). Though the preoccupation with finding numerical values of these parameters was not in retrospect always helpful, certain features of those results contained the seeds of many later developments in this subject. -

THE SOLUBILITY of GASES in LIQUIDS INTRODUCTION the Solubility Data Project Aims to Make a Comprehensive Search of the Lit- Erat

THE SOLUBILITY OF GASES IN LIQUIDS R. Battino, H. L. Clever and C. L. Young INTRODUCTION The Solubility Data Project aims to make a comprehensive search of the lit erature for data on the solubility of gases, liquids and solids in liquids. Data of suitable accuracy are compiled into data sheets set out in a uni form format. The data for each system are evaluated and where data of suf ficient accuracy are available values recommended and in some cases a smoothing equation suggested to represent the variation of solubility with pressure and/or temperature. A text giving an evaluation and recommended values and the compiled data sheets are pUblished on consecutive pages. DEFINITION OF GAS SOLUBILITY The distinction between vapor-liquid equilibria and the solUbility of gases in liquids is arbitrary. It is generally accepted that the equilibrium set up at 300K between a typical gas such as argon and a liquid such as water is gas liquid solubility whereas the equilibrium set up between hexane and cyclohexane at 350K is an example of vapor-liquid equilibrium. However, the distinction between gas-liquid solUbility and vapor-liquid equilibrium is often not so clear. The equilibria set up between methane and propane above the critical temperature of methane and below the critical temperature of propane may be classed as vapor-liquid equilibrium or as gas-liquid solu bility depending on the particular range of pressure considered and the par ticular worker concerned. The difficulty partly stems from our inability to rigorously distinguish between a gas, a vapor, and a liquid, which has been discussed in numerous textbooks. -

Lecture 3. the Basic Properties of the Natural Atmosphere 1. Composition

Lecture 3. The basic properties of the natural atmosphere Objectives: 1. Composition of air. 2. Pressure. 3. Temperature. 4. Density. 5. Concentration. Mole. Mixing ratio. 6. Gas laws. 7. Dry air and moist air. Readings: Turco: p.11-27, 38-43, 366-367, 490-492; Brimblecombe: p. 1-5 1. Composition of air. The word atmosphere derives from the Greek atmo (vapor) and spherios (sphere). The Earth’s atmosphere is a mixture of gases that we call air. Air usually contains a number of small particles (atmospheric aerosols), clouds of condensed water, and ice cloud. NOTE : The atmosphere is a thin veil of gases; if our planet were the size of an apple, its atmosphere would be thick as the apple peel. Some 80% of the mass of the atmosphere is within 10 km of the surface of the Earth, which has a diameter of about 12,742 km. The Earth’s atmosphere as a mixture of gases is characterized by pressure, temperature, and density which vary with altitude (will be discussed in Lecture 4). The atmosphere below about 100 km is called Homosphere. This part of the atmosphere consists of uniform mixtures of gases as illustrated in Table 3.1. 1 Table 3.1. The composition of air. Gases Fraction of air Constant gases Nitrogen, N2 78.08% Oxygen, O2 20.95% Argon, Ar 0.93% Neon, Ne 0.0018% Helium, He 0.0005% Krypton, Kr 0.00011% Xenon, Xe 0.000009% Variable gases Water vapor, H2O 4.0% (maximum, in the tropics) 0.00001% (minimum, at the South Pole) Carbon dioxide, CO2 0.0365% (increasing ~0.4% per year) Methane, CH4 ~0.00018% (increases due to agriculture) Hydrogen, H2 ~0.00006% Nitrous oxide, N2O ~0.00003% Carbon monoxide, CO ~0.000009% Ozone, O3 ~0.000001% - 0.0004% Fluorocarbon 12, CF2Cl2 ~0.00000005% Other gases 1% Oxygen 21% Nitrogen 78% 2 • Some gases in Table 3.1 are called constant gases because the ratio of the number of molecules for each gas and the total number of molecules of air do not change substantially from time to time or place to place. -

Carbon Monoxide Levels and Risks

Carbon Monoxide Levels and Risks CO Level Action CO Level Action 0.1 ppm Natural atmosphere level or clean air. 70-75 ppm Heart patients experience an increase in chest pain. Significant decrease in 1 ppm An increase of 1 ppm in the maximum dai- oxygen available to the myocardium/ ly one-hour exposure is associated with a heart (HbCO 10%). 0.96 percent increase in the risk of hospi- 100 ppm Headache, tiredness, dizziness, nausea talization from cardiovascular disease within 2 hrs of exposure. At 5 hrs, dam- among people over the age of 65. age to hearts and brains. (Lewey & Drabkin) (Circulation: Journal of the AHA, Sept, 2009) 200 ppm Healthy adults will have headache, nau- 3-7 ppm 6% increase in the rate of admission in sea at this level. hospitals of non-elderly for asthma. (L. Shep- pard et al.,Epidemiology, Jan 1999) NIOSH & OSHA recommend evacua- tion of the workplace at this level. 5-6 ppm Significant risk of low birth weight if exposed during last trimester - in a study 400 ppm Frontal headache within 1-2 hours—life of 125,573 pregnancies (Ritz & Yu, Environ. threatening within 3 hours. Health Perspectives, 1999). 500 ppm Concentration in a garage when a cold 9 ppm EPA and WHO maximum outdoor air lev- car is started in an open garage and el, all ages, (TWA, 8 hrs). Maximum allow- warmed up for 2 minutes. (Greiner, 1997) able indoor level (ASHRAE) 800 ppm Healthy adults will have nausea, dizzi- Lowest CO level producing significant ef- ness and convulsions within 45 fects on cardiac function (ST-segment minutes. -

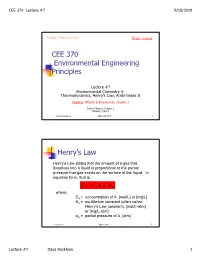

CEE 370 Environmental Engineering Principles Henry's

CEE 370 Lecture #7 9/18/2019 Updated: 18 September 2019 Print version CEE 370 Environmental Engineering Principles Lecture #7 Environmental Chemistry V: Thermodynamics, Henry’s Law, Acids-bases II Reading: Mihelcic & Zimmerman, Chapter 3 Davis & Masten, Chapter 2 Mihelcic, Chapt 3 David Reckhow CEE 370 L#7 1 Henry’s Law Henry's Law states that the amount of a gas that dissolves into a liquid is proportional to the partial pressure that gas exerts on the surface of the liquid. In equation form, that is: C AH = K p A where, CA = concentration of A, [mol/L] or [mg/L] KH = equilibrium constant (often called Henry's Law constant), [mol/L-atm] or [mg/L-atm] pA = partial pressure of A, [atm] David Reckhow CEE 370 L#7 2 Lecture #7 Dave Reckhow 1 CEE 370 Lecture #7 9/18/2019 Henry’s Law Constants Reaction Name Kh, mol/L-atm pKh = -log Kh -2 CO2(g) _ CO2(aq) Carbon 3.41 x 10 1.47 dioxide NH3(g) _ NH3(aq) Ammonia 57.6 -1.76 -1 H2S(g) _ H2S(aq) Hydrogen 1.02 x 10 0.99 sulfide -3 CH4(g) _ CH4(aq) Methane 1.50 x 10 2.82 -3 O2(g) _ O2(aq) Oxygen 1.26 x 10 2.90 David Reckhow CEE 370 L#7 3 Example: Solubility of O2 in Water Background Although the atmosphere we breathe is comprised of approximately 20.9 percent oxygen, oxygen is only slightly soluble in water. In addition, the solubility decreases as the temperature increases. -

Pressure Vs. Volume and Boyle's

Pressure vs. Volume and Boyle’s Law SCIENTIFIC Boyle’s Law Introduction In 1642 Evangelista Torricelli, who had worked as an assistant to Galileo, conducted a famous experiment demonstrating that the weight of air would support a column of mercury about 30 inches high in an inverted tube. Torricelli’s experiment provided the first measurement of the invisible pressure of air. Robert Boyle, a “skeptical chemist” working in England, was inspired by Torricelli’s experiment to measure the pressure of air when it was compressed or expanded. The results of Boyle’s experiments were published in 1662 and became essentially the first gas law—a mathematical equation describing the relationship between the volume and pressure of air. What is Boyle’s law and how can it be demonstrated? Concepts • Gas properties • Pressure • Boyle’s law • Kinetic-molecular theory Background Open end Robert Boyle built a simple apparatus to measure the relationship between the pressure and volume of air. The apparatus ∆h ∆h = 29.9 in. Hg consisted of a J-shaped glass tube that was Sealed end 1 sealed at one end and open to the atmosphere V2 = /2V1 Trapped air (V1) at the other end. A sample of air was trapped in the sealed end by pouring mercury into Mercury the tube (see Figure 1). In the beginning of (Hg) the experiment, the height of the mercury Figure 1. Figure 2. column was equal in the two sides of the tube. The pressure of the air trapped in the sealed end was equal to that of the surrounding air and equivalent to 29.9 inches (760 mm) of mercury. -

Diffusion at Work

or collective redistirbution of any portion of this article by photocopy machine, reposting, or other means is permitted only with the approval of The Oceanography Society. Send all correspondence to: [email protected] ofor Th e The to: [email protected] Oceanography approval Oceanography correspondence POall Box 1931, portionthe Send Society. Rockville, ofwith any permittedUSA. articleonly photocopy by Society, is MD 20849-1931, of machine, this reposting, means or collective or other redistirbution article has This been published in hands - on O ceanography Oceanography Diffusion at Work , Volume 20, Number 3, a quarterly journal of The Oceanography Society. Copyright 2007 by The Oceanography Society. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to copy this article for use in teaching and research. Republication, systemmatic reproduction, reproduction, Republication, systemmatic research. for this and teaching article copy to use in reserved.by The 2007 is rights ofAll granted journal Copyright Oceanography The Permission 20, NumberOceanography 3, a quarterly Society. Society. , Volume An Interactive Simulation B Y L ee K arp-B oss , E mmanuel B oss , and J ames L oftin PURPOSE OF ACTIVITY or small particles due to their random (Brownian) motion and The goal of this activity is to help students better understand the resultant net migration of material from regions of high the nonintuitive concept of diffusion and introduce them to a concentration to regions of low concentration. Stirring (where variety of diffusion-related processes in the ocean. As part of material gets stretched and folded) expands the area available this activity, students also practice data collection and statisti- for diffusion to occur, resulting in enhanced mixing compared cal analysis (e.g., average, variance, and probability distribution to that due to molecular diffusion alone.