The Singer and the Voice: Where Is the Music?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume-13-Skipper-1568-Songs.Pdf

HINDI 1568 Song No. Song Name Singer Album Song In 14131 Aa Aa Bhi Ja Lata Mangeshkar Tesri Kasam Volume-6 14039 Aa Dance Karen Thora Romance AshaKare Bhonsle Mohammed Rafi Khandan Volume-5 14208 Aa Ha Haa Naino Ke Kishore Kumar Hamaare Tumhare Volume-3 14040 Aa Hosh Mein Sun Suresh Wadkar Vidhaata Volume-9 14041 Aa Ja Meri Jaan Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Jawab Volume-3 14042 Aa Ja Re Aa Ja Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Ankh Micholi Volume-3 13615 Aa Mere Humjoli Aa Lata Mangeshkar Mohammed RafJeene Ki Raah Volume-6 13616 Aa Meri Jaan Lata Mangeshkar Chandni Volume-6 12605 Aa Mohabbat Ki Basti BasayengeKishore Kumar Lata MangeshkarFareb Volume-3 13617 Aadmi Zindagi Mohd Aziz Vishwatma Volume-9 14209 Aage Se Dekho Peechhe Se Kishore Kumar Amit Kumar Ghazab Volume-3 14344 Aah Ko Chahiye Ghulam Ali Rooh E Ghazal Ghulam AliVolume-12 14132 Aah Ko Chajiye Jagjit Singh Mirza Ghalib Volume-9 13618 Aai Baharon Ki Sham Mohammed Rafi Wapas Volume-4 14133 Aai Karke Singaar Lata Mangeshkar Do Anjaane Volume-6 13619 Aaina Hai Mera Chehra Lata Mangeshkar Asha Bhonsle SuAaina Volume-6 13620 Aaina Mujhse Meri Talat Aziz Suraj Sanim Daddy Volume-9 14506 Aaiye Barishon Ka Mausam Pankaj Udhas Chandi Jaisa Rang Hai TeraVolume-12 14043 Aaiye Huzoor Aaiye Na Asha Bhonsle Karmayogi Volume-5 14345 Aaj Ek Ajnabi Se Ashok Khosla Mulaqat Ashok Khosla Volume-12 14346 Aaj Hum Bichade Hai Jagjit Singh Love Is Blind Volume-12 12404 Aaj Is Darja Pila Do Ki Mohammed Rafi Vaasana Volume-4 14436 Aaj Kal Shauqe Deedar Hai Asha Bhosle Mohammed Rafi Leader Volume-5 14044 Aaj -

Vocal Grade 4

VOCAL GRADE 4 Introduction Welcome to Grade 4 You are about to start the wonderful journey of learning to sing, a journey that is challenging, but rewarding and enjoyable! Whether you want to jam with a band or enjoy singing solo, this series of lessons will get you ready to perform with skill & confidence. What will you learn? Grade 4 covers the following topics : 1) Guruvandana and Saraswati vandana 2) Gharanas in Indian Classical Music 3) Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande 4) Tanpura 5) Lakshan Geet 6) Music & Psychology 7) Raag Bhairav 8) Chartaal 9) Raag Bihag 10) Raag and Time Theory 11) Raag Kafi 12) Taal Ektaal 13) Bada Khyal 14) Guessing a Raag 15) Alankar 1 What You Need Harmonium /Synthesizer Electronic Tabla / TablaApp You can learn to sing without any of the above instruments also and by tapping your feet, however you will get a lot more out of this series if you have a basic harmonium and a digital Tabla to practice. How to Practice At Home Apart from this booklet for level 1, there will be video clippings shown to you for each topic in all the lessons. During practice at home, please follow the method shown in the clippings. Practice each lesson several times before meeting for the next lesson. A daily practice regime of a minimum of 15 minutes will suffice to start with. Practicing with the harmonium and the digital Tabla will certainly have an added advantage. DigitalTablamachinesorTablasoftware’sareeasilyavailableandideallyshould beusedfor daily practice. 2 Lesson 1 GURUVANDANA SARASWATI VANDANA & Guruvandana Importance of Guruvandana : The concept of Guru is as old as humanity itself. -

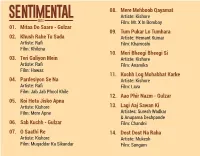

Sentimental Booklet for Web Copy

08. Mere Mehboob Qayamat Artiste: Kishore Film: Mr. X In Bombay 01. Mitaa Do Saare - Gulzar 09. Tum Pukar Lo Tumhara 02. Khush Rahe Tu Sada Artiste: Hemant Kumar Artiste: Rafi Film: Khamoshi Film: Khilona 10. Meri Bheegi Bheegi Si 03. Teri Galiyon Mein Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Rafi Film: Anamika Film: Hawas 11. Kuchh Log Mohabbat Karke 04. Pardesiyon Se Na Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Rafi Film: Lava Film: Jab Jab Phool Khile 12. Aao Phir Nazm - Gulzar 05. Koi Hota Jisko Apna Artiste: Kishore 13. Lagi Aaj Sawan Ki Film: Mere Apne Artistes: Suresh Wadkar & Anupama Deshpande 06. Sab Kuchh - Gulzar Film: Chandni 07. O Saathi Re 14. Dost Dost Na Raha Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Mukesh Film: Muqaddar Ka Sikandar Film: Sangam 2 3 15. Hui Sham Unka Khayal 22. Din Dhal Jaye Haye Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Film: Mere Hamdam Mere Dost Film: Guide 01. Mitaa Do Saare - Gulzar 16. Kuchh To Log Kahenge 23. Mere Toote Huye Dil Se 02. Khush Rahe Tu Sada Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Mukesh Artiste: Rafi Film: Amar Prem Film: Chhalia Film: Khilona 17. Waqt Karta Jo Wafa 24. Hue Hum Jinke Liye 03. Teri Galiyon Mein Artiste: Mukesh Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Film: Dil Ne Pukara Film: Deedar Film: Hawas 18. Patthar Ke Sanam 25. Koi Sagar Dil Ko Bahlata 04. Pardesiyon Se Na Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Film: Patthar Ke Sanam Film: Dil Diya Dard Liya Film: Jab Jab Phool Khile 19. Khilona Jan Kar Tum To 26. Chandi Ki Deewar 05. Koi Hota Jisko Apna Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Mukesh Artiste: Kishore Film: Khilona Film: Vishwas Film: Mere Apne 20. -

A Nonlinear Study on Time Evolution in Gharana

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 15 April 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201904.0157.v1 A NONLINEAR STUDY ON TIME EVOLUTION IN GHARANA TRADITION OF INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC Archi Banerjee1,2*, Shankha Sanyal1,2*, Ranjan Sengupta2 and Dipak Ghosh2 1 Department of Physics, Jadavpur University 2 Sir C.V. Raman Centre for Physics and Music Jadavpur University, Kolkata: 700032 India *[email protected] * Corresponding author Archi Banerjee: [email protected] Shankha Sanyal: [email protected]* Ranjan Sengupta: [email protected] Dipak Ghosh: [email protected] © 2019 by the author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons CC BY license. Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 15 April 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201904.0157.v1 A NONLINEAR STUDY ON TIME EVOLUTION IN GHARANA TRADITION OF INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC ABSTRACT Indian classical music is entirely based on the “Raga” structures. In Indian classical music, a “Gharana” or school refers to the adherence of a group of musicians to a particular musical style of performing a raga. The objective of this work was to find out if any characteristic acoustic cues exist which discriminates a particular gharana from the other. Another intriguing fact is if the artists of the same gharana keep their singing style unchanged over generations or evolution of music takes place like everything else in nature. In this work, we chose to study the similarities and differences in singing style of some artists from at least four consecutive generations representing four different gharanas using robust non-linear methods. For this, alap parts of a particular raga sung by all the artists were analyzed with the help of non linear multifractal analysis (MFDFA and MFDXA) technique. -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles Music of Mughal-e-Azam. Bai, Begum, Dasi, Devi and Jan’s on gramophone records, Spiritual message of Gandhiji, Lyricist Gandhiji, Parlophon records in Sri Lanka, The First playback singer in Malayalam Films 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US $ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full -

Bhimsen Joshi and the Kirana Gharana«

Bhimsen Joshi and the Kirana Gharana« CHETAN KARNAN! I. INTRODUCIlON he Kirana ghariinii laid emphasis on melody rather than rhythm. In our times, Bhimsen Joshi has become the most popular artist of this gharana Tbecause he combines melody with vinuosity. His teacherSawaiGandharva combined melody with the euphony of his voice. Sawai Gandharva's teacher. Abdul Karim Khan, was a pioneer and the founder of the Kiranagharana. He had arare gift for making melodic phrases in any raga he chose to sing. Abdul Karim Khan had another notable disciple in Roshan Ara Begam, but Sawai Gandharva was by far his most distinguished disciple. Sawai Gandharva's important disciples are Bhimsen Joshi, Gangubai Hangal and Firoz Dastur. In later sections of this chapter I have emphasized the rugged masculinityof GangubaiHangal's voice. I have also discussed the systematic elaboration of ragas presentedby Firoz Dastur. Just as the Gwalior gharana has two lines represented by Haddu Khan and Hassu Khan, the Kirana gharana has two lines represented by Abdul Karim Khan and Abdul Wahid Khan. Abdul Wahid Khan combined melody with systematic elaboration of raga. He laid emphasis on the placid flow of music and preferred tosing in Jhoomra tala offourteen beats. By elaboratinga raga in slow tempo, he showed a facet of melody distinct from Abdul Karim Khan. His most di stinguished disciples were Hirabai Barodekar and Pran Nath, who sang with euphony in slow tempo. It is sheer good luck that the pioneers of the Kirana gharana, Abdul Karim Khan and Abdul Wahid Khan, were saved from oblivion by the gramophone COmpanies. -

A Tribute to Pandit Bhimsen Joshi Issue,By Pragya Date Mishra Thakur

Raag-Rang Newsletter Vol. 2 March, 2011 SOOR SANSKAR A Tribute To Pandit Bhimsen Joshi Issue,By Pragya Date Mishra Thakur This second Raag-Rang Pandit Bhimsen Joshi was so in the South Indian language. He newsletter would be incomplete passionate about music from an early would move in an out of styles and without a tribute to our revered age that he left home at the tender age language restrictions as if no such Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, who passed of 11 in a quest for a guru. He was artificial boundaries ever existed. This away on January 24th, 2011 in Pune, eventually found and brought back spirit of unity and oneness was so leaving behind a legion of bereft home but there was no stopping him clearly evident in his unforgettable music lovers. Pandit Bhimsen Joshi from pursuing his dream after that rendition of the song that became a was a recipient of the Bharat Ratna event. He went on to become the call for national integration and unity and many other awards during his recipient of every possible award an in India: Mile Sur Mera Tumhara. illustrious lifetime and was honor that a musician in India can Raag-Rang, now in its third accorded a state funeral receive, culminating with the highest year, through its efforts, hopes to accompanied by a 21 gun salute at honor, the Bharat Ratna. cultivate the same dedication and the the Vaikunth Crematorium of Pune, same passion in the young performers Maharashtra. Mourners gathered and musicians that we support and in large numbers to pay homage encourage. -

Gharana: the True Meaning - Gundecha Brothers

Gharana: The true meaning - Gundecha Brothers Our probe of the term ‘Gharana’ may be incomplete if we dwell only on the literal meaning of the term. Hence the in-depth examination is a must. It should be kept in mind that, musical ‘Gharana’ (or tradition, in a general sense) is born out of the genius of a master and his creative abilities. Even then, gharana imbibes the traits of some auxiliaries; which are not necessarily a gharana of their own. It can easily be seen to be a current of musical thoughts and the perpetuation of the tradition. Thus said, we should never attempt to fit an immobile frame. The only address of such a current will be a stream of creative thoughts. But, it has been a wrong practice to recognise and preach the term gharana as a fixed entity. The gharana itself is a product of such a stream. Also, it will be an injustice to perceive the stream of music with a fixed set of concepts. A contemplated study of a musical gharana will reveal us that it were the product of a master; his creative thoughts, his perceptions, his aesthetic thinking, his nature and even his limitations. After the master, his gharana propitiates such type of music only. A good study also tells about a gharana’s specialities like: the voice culture, tempi of singing, perception of ragas, compositions, the improvisation of text as well as rhythm etc. All such faculties compile and give rise to a gharana which has a flavour of its own. Amongst all, the voice culture maintains the highest importance in any gharana. -

The Great Musician SD Burman

JUNE 2018 www.Asia Times.US PAGE 1 www.Asia Times.US Globally Recognized Editor-in-Chief: Azeem A. Quadeer, M.S., P.E. JUNE 2018 Vol 9, Issue 6 Punjab govt backs agitating farmers, Sidhu slams Centre The Punjab government came out in support of the state’s agitating farmers as minister ises, the farmers would not have been in Navjot Singh Sidhu slammed the Centre for ignoring the agriculture sector. such a sorry state of affairs. Sidhu assured the protesting farmers that A 10-day long nationwide agitation against the alleged anti-farmer practices of the Union the Punjab government was sympathetic government began today and as part of the protest, the supply of vegetables, fruits, milk to their demands and stood shoulder to and other items to various parts of Punjab and Haryana was stopped. shoulder with them. The Punjab local bodies and tourism In his unique way, the cricketer-turned-politician visited village Patto along with Con- minister stressed that the Swamina- gress MLAs Kuljit Singh Nagra and Gurpreet Singh and bought milk and vegetables from than Commission report was not being farmers to highlight their significant contribution in the development of the nation. implemented and farmers were not getting adequate price for their crops, leading to “If the country is to be saved then saving farm sector ought to be a priority,” Sidhu said escalation in farmer suicides. adding that if the ruling NDA government at the Centre had fulfilled their pre-poll prom- Suggesting linkage of Minimum Support Price (MSP) of crops with oil prices, the min- ister went on to say that in the last 25 years, oil prices increased twelve fold whereas the MSP increased by only five per cent. -

Gazzal Has Acquired a Respectable Niche in the Hearts of Indian

It gives us immense pleasure in inviting you to a Unique Cultural Evening Bahar–E–Ghazal This evening will unravel and unfold the intricacies of the world of Ghazals. Ghazals have acquired a respectable niche in the hearts of Indian music lovers. It represents one of the facets of rich heritage of poetic nuances, embellished by the base of Indian Classical music. The artists will present: Well-known Ghazals popularized by earlier stalwarts New Ghazals written and composed by local artists In addition to Urdu/Hindi, some Ghazals will be presented in Punjabi, Marathi and Gujarati. Concept: Dr. Vivek Khadilkar Anchors: Arin (Dolly) Vanjari & Dharam Chouhan Artists: Avtar Chand (Avvi) & Hemkalyan Bapat Accompanists: Nitin Damle - Harmonium Amod Dandawate - Tabla Date: Saturday June 29, 2013 Time: 6:00 PM Venue: Arellano Theater (Under Glass Pavilion) Levering Hall, Johns Hopkins University, 3400 North Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21201 Contact: Mangla Khadilkar (215) 357-5383 Ashwini Nagarkar (443)812-1548 Raju Nagarkar (443) 812-1546 Donation: $15 per person or $25 per couple Artists Hemkalyan Bapat: Hemkalyan is a computer engineer by profession but a musician at heart. He comes from a family of musicians. Both his parents are exponents of the Kirana gharana gayaki. His father Dr. Laxmikant Bapat is a disciple of Lt. Pt. Bhimsen Joshi and mother Mrs. Minaxi Bapat is a disciple of Dr. Prabha Atre. Hemkalyan's training in music started at home at an early age with his parents. He has studied tabla, vocal music, harmonium and kathak dance for a number of years. He has accompanied on tabla well known vocalists like Smt. -

Subscribe Rs

NEW DELHI TIMES R.N.I. No 53449/91 DL-SW-1/4124/20-22 (Monday/Tuesday same week) (Published Every Monday) New Delhi Page 24 Rs. 7.00 25 - 31 January 2021 Vol - 30 No. 52 Email : [email protected] Founder : Dr. Govind Narain Srivastava ISSN -2349-1221 Shavkat Mirziyoyev’s Presidency has Opportunities are not created heralded a new era in Uzbekistan by anybody exclusively Since Shavkat Mirziyoyev took the office of the President of Uzbekistan, the country In life as we navigate through the endless clusters of events, has not only witnessed an unprecedented era of all round development but we so many a times miss out on certain things, like the has also enhanced its standing in the international arena, emerging opportunity to go on a school trip, or a new friendship or to take as a leading power in Central Asia. Shavkat Mirziyoyev has on a new project, or a career. been hailed as the champion of reforms in Uzbekistan. Shavkat Mirziyoyev was appointed by the Supreme Assembly as the There are many things at play as the opportunity that are being interim President... presented to us in our daily life. Sometimes we deny... By Dr. Ankit Srivastava Page 3 By Dr. Pramila Srivastava Page 24 By NDT Special Bureau Page 2 America’s era of mediocrity is India’s Republic Day Parade Pakistan spoiling the Western Allied now in new hands A humble tribute to our Martyrs supported Afghan Peace process As President Joe Biden and his designer-wearing, multi- India became independent on 15th August, 1947, after Currently the Afghan Taliban and the Afghan government ethnic running mate Vice-President Kamala Harris.. -

Indian Council for Cultural Relations Empanelment Artists

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Sponsored by Occasion Social Media Presence Birth Empanel Category/ ICCR including Level Travel Grants 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 9/27/1961 Bharatanatyam C-52, Road No.10, 2007 Outstanding 1997-South Korea To give cultural https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Film Nagar, Jubilee Hills Myanmar Vietnam Laos performances to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ Hyderabad-500096 Combodia, coincide with the https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk Cell: +91-9848016039 2002-South Africa, Establishment of an https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o +91-40-23548384 Mauritius, Zambia & India – Central https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc [email protected] Kenya American Business https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 [email protected] 2004-San Jose, Forum in Panana https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kSr8A4H7VLc Panama, Tegucigalpa, and to give cultural https://www.ted.com/talks/ananda_shankar_jayant_fighti Guatemala City, Quito & performances in ng_cancer_with_dance Argentina other countries https://www.youtube.com/user/anandajayant https://www.youtube.com/user/anandasj 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 8/13/1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ