ARMS TRACING Perspectives on Control, Traffic and Use of Illegal Weapons in Colombia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who the Hell Is Bob? After Reading This Book, the Answer Wi.Ll~An Easy One: Someone You Will Not Soon Forget

~- asxr anc ror gooo reason. Hue, DUO VValSf11S hardly a household name, yet for the last forty years he has found himself popping up in the middle of countless high-profile events, his own life inextricably entwined with the fa- mous, the powerful, and the notorious. Who else has a resume that includes such disparate accomplishments as helping to create March Madness, coordinating disaster relief for earthquake victims, producing the successful 1990 Goodwill Games, converting Stalin's Dacha to a hotel, and resurrecting Mr. Blackwell's career. Author Steve Rudman spices solid research and insider secrets with a generous dose of razor-sharp wit as he tells Bob's in- credibly entertaining story. Politics, history, intrigue, romance, celebrity gossip - it's all there in the life of one "ordinary" man. Who the hell is Bob? After reading this book, the answer wi.lL~an easy one: Someone you will not soon forget. Bob is a unique individual who proves over and over that a single individual can make a difference. His life is a wonderful example of what courage, determination, and energy can accomplish. · Eduard Shevardnadze, President, Republic of Georgia Some people go through life silting on the sidelines. Bob Walsh has always been a player, and the world is more interesting as a result. · Bill Russell, NBA Hall of Famer, Seattle, Washington Bob's story speaks to all of us who seek our own place on earth and whose whisper is louder than thunder. · Mr. Blackwell, creator "Worst Dressed list," Los Angeles, California Bob Walsh and I have been friends for twenty years. -

The AK47: Full Auto Conversion for Dummies by Royi “Uncle Ro” Eltink Author of “Uncle Ro’ Extreme Survival” and “The Paramilitary Commando” Series

The AK47: Full Auto Conversion for Dummies By Royi “Uncle Ro” Eltink Author of “Uncle Ro’ Extreme Survival” and “The Paramilitary Commando” series. Disclaimer: This is for educational purposes only! The author fully disclaims anything the reader does with this information. In some countries and places this information can be prohibited by law, you act on your own responsibility now. An AK47 and his happy owner Preamble The AK47 has an long and infamous history, as the world’s bestseller on the gun market, it has seen every conflict since its introduction in 1947. It is cheap, easy to manufacture and maintain and anyone who can hold a rifle and pull a trigger can be an expert on this weapon in an half hour. Of course, every respectable nation on this planet has build one or two versions of the Russian rifle, famous are the Chinese, German, Finnish (Valmet), Israeli (Galil), South-African and the Dutch…..and many more I did not mention. Let’s begin with an wishlist Of course, you cant just read this thing and finish reading and ending up with an full auto AK.. You have to get you’re hands on a couple of things first. You need the normal civil, sports, version of the AK47 or an AKM. Further you might want to have: - Proper license for all these things, and the thing you are going to build - Full auto parts set, I will point out how to make an template to fit these in. - Full auto bolt carrier in those models who don’t have one. -

International Military Cartridge Rifles and Bayonets

INTERNATIONAL MILITARY CARTRIDGE RIFLES AND BAYONETS The following table lists the most common international military rifles, their chambering, along with the most common bayonet types used with each. This list is not exhaustive, but is intended as a quick reference that covers the types most commonly encountered by today’s collectors. A Note Regarding Nomenclature: The blade configuration is listed, in parentheses, following the type. There is no precise dividing line between what blade length constitutes a knife bayonet vs. a sword bayonet. Blades 10-inches or shorter are typically considered knife bayonets. Blades over 12-inches are typically considered sword bayonets. Within the 10-12 inch range, terms are not consistently applied. For purposes of this chart, I have designated any blade over 12 inches as a sword bayonet. Country Rifle Cartridge Bayonet (type) Argentina M1879 Remington 11.15 x 58R Spanish M1879 (sword) Rolling-Block M1888 Commission 8 x 57 mm. M1871 (sword) Rifle M1871/84 (knife) M1891 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1891 (sword) M1891 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. None Cavalry Carbine M1891 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1891/22 (knife) Engineer Carbine [modified M1879] M1891/22 (knife) [new made] M1909 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1909 First Pattern (sword) M1909 Second Pattern (sword) M1909/47 (sword) M1909 Mauser 7.65 x 53 mm. M1909 Second Cavalry Carbine Pattern (sword) M1909/47 (sword) FN Model 1949 7.65 x 53 mm. FN Model 1949 (knife) FN-FAL 7.62 mm. NATO FAL Type A (knife) FAL Type C (socket) © Ralph E. Cobb 2007 all rights reserved Rev. -

William Chislett

ANTI-AMERICANISM IN SPAIN: THE WEIGHT OF HISTORY William Chislett Working Paper (WP) 47/2005 18/11/2005 Area: US-Transatlantic Dialogue – WP Nº 47/2005 18/11/2005 Anti-Americanism in Spain: The Weight of History William Chislett ∗ Summary: Spain’s feelings toward the United States are the coldest in Europe after Turkey, according to a poll by the German Marshall Fund. And they have been that way for a very long time. The country’s thermometer reading on a scale of 0-100 was 42º in 2005, only surpassed by Turkey’s 28º and compared with an average of 50º for the 10 countries surveyed (see Figure 1). The same degree of coldness towards the United States was brought out in the 16-country Pew Global Attitudes Project where only 41% of Spaniards said they had a very or somewhat favourable view of the United States. This surprises many people. After all, Spain has become a vibrant democracy and a successful market economy since the right-wing dictatorship of General Franco ended in 1975 with the death of the Generalísimo. Why are Spaniards so cool towards the United States? Spain’s feelings toward the United States are the coldest in Europe after Turkey, according to a poll by the German Marshall Fund. And they have been that way for a very long time. The country’s thermometer reading on a scale of 0-100 was 42º in 2005, only surpassed by Turkey’s 28º and compared with an average of 50º for the 10 countries surveyed (see Figure 1). -

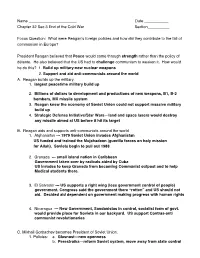

Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section___Focus Question

Name ______________________ Date ___________ Chapter 32 Sec 3 End of the Cold War Section__________ Focus Question: What were Reaganʼs foreign policies and how did they contribute to the fall of communism in Europe? President Reagan believed that Peace would come through strength rather than the policy of détente. He also believed that the US had to challenge communism to weaken it. How would he do this? 1. Build up military-new nuclear weapons 2. Support and aid anti-communists around the world A. Reagan builds up the military. 1. largest peacetime military build up 2. Billions of dollars to development and productions of new weapons, B1, B-2 bombers, MX missile system 3. Reagan knew the economy of Soviet Union could not support massive military build up 4. Strategic Defense Initiative/Star Wars—land and space lasers would destroy any missile aimed at US before it hit its target B. Reagan aids and supports anti-communists around the world 1. Afghanistan --- 1979 Soviet Union invades Afghanistan US funded and trained the Mujahadeen (guerilla forces on holy mission for Allah). Soviets begin to pull out 1988 2. Grenada --- small island nation in Caribbean Government taken over by radicals aided by Cuba US invades to keep Granada from becoming Communist outpost and to help Medical students there. 3. El Salvador --- US supports a right wing (less government control of people) government. Congress said the government there “rotten” and US should not aid. Decided aid dependent on government making progress with human rights 4. Nicaragua --- New Government, Sandanistas in control, socialist form of govt. -

2018 COMMITTEE AMENDMENT Bill No. SPB 7026 Ì831648BÎ831648 Page 1 of 24 2/26/2018 2:07:33 PM 595-03718-18

Florida Senate - 2018 COMMITTEE AMENDMENT Bill No. SPB 7026 831648 Ì831648BÎ LEGISLATIVE ACTION Senate . House . The Committee on Rules (Rodriguez) recommended the following: 1 Senate Amendment to Amendment (345360) (with title 2 amendment) 3 4 Between lines 209 and 210 5 insert: 6 Section 8. Section 790.30, Florida Statutes, is created to 7 read: 8 790.30 Assault weapons.— 9 (1) DEFINITIONS.—As used in this section, the term: 10 (a) “Assault weapon” means: 11 1. A selective-fire firearm capable of fully automatic, Page 1 of 24 2/26/2018 2:07:33 PM 595-03718-18 Florida Senate - 2018 COMMITTEE AMENDMENT Bill No. SPB 7026 831648 Ì831648BÎ 12 semiautomatic, or burst fire at the option of the user or any of 13 the following specified semiautomatic firearms: 14 a. Algimec AGM1. 15 b. All AK series, including, but not limited to, the 16 following: AK, AK-47, AK-74, AKM, AKS, ARM, MAK90, MISR, NHM90, 17 NHM91, Rock River Arms LAR-47, SA 85, SA 93, Vector Arms AK-47, 18 VEPR, WASR-10, and WUM. 19 c. All AR series, including, but not limited to, the 20 following: AR-10, AR-15, Armalite AR-180, Armalite M-15, AR-70, 21 Bushmaster XM15, Colt AR-15, DoubleStar AR rifles, DPMS tactical 22 rifles, Olympic Arms, Rock River Arms LAR-15, and Smith & Wesson 23 M&P15 rifles. 24 d. Barrett 82A1 and REC7. 25 e. Beretta AR-70 and Beretta Storm. 26 f. Bushmaster automatic rifle. 27 g. Calico Liberty series rifles. 28 h. Chartered Industries of Singapore SR-88. -

Redalyc.Lawfare: the Colombian Case

Revista Científica General José María Córdova ISSN: 1900-6586 [email protected] Escuela Militar de Cadetes "General José María Córdova" Colombia Padilla, Juan Manuel Lawfare: The Colombian Case Revista Científica General José María Córdova, vol. 10, núm. 10, 2012, pp. 107-142 Escuela Militar de Cadetes "General José María Córdova" Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=476248923006 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Estudios militares Revista Científica “General José María Córdova”, Bogotá D.C. (Colombia) Sección . Vol 10, Núm 10, Año 2012, Junio REVCGJMC.10(10): 107-142, 2012 Lawfare: The Colombian Case * Guerra jurídica: el caso colombiano La guerre juridique: le cas colombien Guerra jurídica: o caso colombiano Recibido: 20 de Febrero de 2012. Aceptado: 15 de Abril de 2012. Juan Manuel Padillaa * Researche monograph originally presented to the School of Advanced Military Studies of the United States Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, approved for Revista Cientifica Public Release. “General José María Córdova”, Bogotá D.C. (Colombia) a Máster en Ciencias y Artes Militares , U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. Director Sección Estudios militares. de la Escuela Militar de Cadetes “General José María Córdova”. Comentarios a: jumapac@gmail. Vol 10 , Núm 10, Año 2012, com Junio, pp. 107-142 ISSN 1900- 6586 108 Juan Manuel Padilla Abstract. The terrorist groups in Colombia have applied Mao’s theory of protracted people’s war, seeking to use all available means of struggle to achieve their revolutionary goals by counteracting govemment policy. -

Alite's Archives: Bro Dadcagting from Ok the Outlaw Empirek

Big Changes In Amateur Service Rules On Page 65 D08635 APRIL 2000 4IP A Loo How WBT Folght Soviet Propaganda Alite's Archives: Bro_dadcagting From ok The Outlaw Empirek, cene, The Pirate's Den, I Got Started, And Much More! CARRY THE WORLD '''''',--4000.111111111P WITH YOU! s. r. Continuous Coverage: 145 100 kHz to 1299.99995* MHz! 1.i.1f:s1711711.:: 'Cellular telephone frequencies are docked and cannot be restored. VR-500 RECEIVER All Mode Reception: COMMUNICATIONS FM, Wide -FM, USB LSB, CW, and AM! Huge Memory Capacity: 1091 Channels! B.W P.SET Ultra Compact Size! STEP 58 mm x 24 mm x 95 mm SCHOCN MW/MC 220 g including Antenna / Battery) MEMO 1ozCP.. CD MODE PW Simulated display / keypad Illumination SCH/rmS . SW/SC S 40SET/NAMEIrk arso LAMP ' ATT Actual Size CODW CIO421,et Features *Multiple Power Source Capability Huge 1091-ch Memory System *Convenience Features *Direct Keypad Frequency Entry With Search & Scan 1 MHz Fast Steps Front-end 20 dB *Large High -Output Speaker Regular Memories 11000 ch) Attenuator RF Squelch 'Power On / Polycarbonate Case Search Band Memories10 ch) Power Off Timers Adjustable *Real -Time 60-ch* Band Scope Preset Channel Memories Battery Saver Extensive Menu `Range 6 MHz / Step 100 kHz (19 ch +10 Weather Channels` Customization Clone Capability ,',1.1F11 *Full Illumination For Dual Watch Memories (10 ch` Computer Control Display And Keypad Priority Memory (1 ch) COMMUNICATIONS RECEIVER Mb *Versatile Squelch / Smart SearchTM Memories as Monitor Key (11/21/31/41 ch) Ct--2 VR-500 *Convenient "Preset" All -Mode Wideband Receiver OD CD0 0 ®m Operating Mode gg YAE SU ©1999 Yaesu USA, 17210 Edwards Road. -

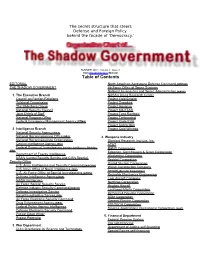

Table of Contents

The secret structure that steers Defense and Foreign Policy behind the facade of 'Democracy.' SUMMER 2001 - Volume 1, Issue 3 from TrueDemocracy Website Table of Contents EDITORIAL North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) THE SHADOW GOVERNMENT Air Force Office of Space Systems National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) 1. The Executive Branch NASA's Ames Research Center Council on Foreign Relations Project Cold Empire Trilateral Commission Project Snowbird The Bilderberg Group Project Aquarius National Security Council Project MILSTAR Joint Chiefs of Staff Project Tacit Rainbow National Program Office Project Timberwind Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Project Code EVA Project Cobra Mist 2. Intelligence Branch Project Cold Witness National Security Agency (NSA) National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) 4. Weapons Industry National Reconnaissance Organization Stanford Research Institute, Inc. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) AT&T Federal Bureau of Investigation , Counter Intelligence Division RAND Corporation (FBI) Edgerton, Germhausen & Greer Corporation Department of Energy Intelligence Wackenhut Corporation NSA's Central Security Service and CIA's Special Bechtel Corporation Security Office United Nuclear Corporation U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Walsh Construction Company U.S. Navy Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) Aerojet (Genstar Corporation) U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) Reynolds Electronics Engineering Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) Lear Aircraft Company NASA Intelligence Northrop Corporation Air Force Special Security Service Hughes Aircraft Defense Industry Security Command (DISCO) Lockheed-Maritn Corporation Defense Investigative Service McDonnell-Douglas Corporation Naval Investigative Service (NIS) BDM Corporation Air Force Electronic Security Command General Electric Corporation Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) PSI-TECH Corporation Federal Police Agency Intelligence Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) Defense Electronic Security Command Project Deep Water 5. -

Download Enemy-Threat-Weapons

UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS THE BASIC SCHOOL MARINE CORPS TRAINING COMMAND CAMP BARRETT, VIRGINIA 22134-5019 ENEMY THREAT WEAPONS B2A2177 STUDENT HANDOUT/SELF PACED INSTRUCTION Basic Officer Course B2A2177 Enemy Threat Weapons Enemy Threat Weapons Introduction In 1979, the Soviets invaded Afghanistan. The Soviets assumed this would be a short uneventful battle; however, the Mujahadeen had other plans. The Mujahadeen are guardians of the Afghani way of live and territory. The Soviets went into Afghanistan with the latest weapons to include the AK-74, AKS-74, and AKSU-74, which replaced the venerable AK-47 in the Soviet Arsenals. The Mujahadeen were armed with Soviet-made AK-47s. This twist of fate would prove to be fatal to the Soviets. For nearly 11 years, the Mujahadeen repelled the Soviet attacks with Soviet-made weapons. The Mujahadeen also captured many newer Soviet small arms, which augmented their supplies of weaponry. In 1989, the Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan back to the other side of the mountain. The Mujahadeen thwarted a communist take- over with their strong will to resist and the AK-47. This is important to you because it illustrates what an effective weapon the AK-47 is, and in the hands of a well-trained rifleman, what can be accomplished. Importance This is important to you as a Marine because there is not a battlefield or conflict that you will be deployed to, where you will not find a Kalashnikov AK-47 or variant. In This Lesson This lesson will cover history, evolution, description, and characteristics of foreign weapons. -

The Drug Trade in Colombia: a Threat Assessment

DEA Resources, For Law Enforcement Officers, Intelligence Reports, The Drug Trade in Colombia | HOME | PRIVACY POLICY | CONTACT US | SITE DIRECTORY | [print friendly page] The Drug Trade in Colombia: A Threat Assessment DEA Intelligence Division This report was prepared by the South America/Caribbean Strategic Intelligence Unit (NIBC) of the Office of International Intelligence. This report reflects information through December 2001. Comments and requests for copies are welcome and may be directed to the Intelligence Production Unit, Intelligence Division, DEA Headquarters, at (202) 307-8726. March 2002 DEA-02006 CONTENTS MESSAGE BY THE ASSISTANT THE HEROIN TRADE IN DRUG PRICES AND DRUG THE COLOMBIAN COLOMBIA’S ADMINISTRATOR FOR COLOMBIA ABUSE IN COLOMBIA GOVERNMENT COUNTERDRUG INTELLIGENCE STRATEGY IN A LEGAL ● Introduction: The ● Drug Prices ● The Formation of the CONTEXT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Development of ● Drug Abuse Modern State of the Heroin Trade Colombia ● Counterdrug ● Cocaine in Colombia DRUG RELATED MONEY ● Colombian Impact of ● Colombia’s 1991 ● Heroin Opium-Poppy LAUNDERING AND Government Institutions Involved in Constitution ● Marijuana Cultivation CHEMICAL DIVERSION ● Opium-Poppy the Counterdrug ● Extradition ● Synthetic Drugs Eradication Arena ● Sentencing Codes ● Money Laundering ● Drug-Related Money ● Opiate Production ● The Office of the ● Money Laundering ● Chemical Diversion Laundering ● Opiate Laboratory President Laws ● Insurgents and Illegal “Self- ● Chemical Diversion Operations in ● The Ministry of ● Asset Seizure -

Illicit Trafficking in Firearms, Their Parts, Components and Ammunition To, from and Across the European Union

Illicit Trafficking in Firearms, their Parts, Components and Ammunition to, from and across the European Union REGIONAL ANALYSIS REPORT 1 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Illicit Trafficking in Firearms, their Parts, Components and Ammunition to, from and across the European Union UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2020 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Illicit Trafficking in Firearms, their Parts, Components and Ammunition to, from and across the European Union REGIONAL ANALYSIS REPORT UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2020 © United Nations, 2020. All rights reserved, worldwide. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copy- right holder, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. UNODC would appreciate receiving a copy of any written output that uses this publication as a source at [email protected]. DISCLAIMERS This report was not formally edited. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNODC, nor do they imply any endorsement. Information on uniform resource locators and links to Internet sites contained in the present publication are provided for the convenience of the reader and are correct at the time of issuance. The United Nations takes no responsibility for the continued accuracy of that information or for the content of any external website. This document was produced with the financial support of the European Union. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect