Daughters, Mothers, and Friends in the Narrative of Carme Riera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Another Country

Presents IN ANOTHER COUNTRY A Kino Lorber Release 333 West 39 Street, Suite 503 New York, NY 10018 (212) 629-6880 www.kinolorber.com Press Contacts: Rodrigo Brandão – [email protected] Matt Barry – [email protected] SYNOPSIS A young film student and her mother run away to the seaside town of Mohang to escape their mounting debt. The young woman begins writing a script for a short film in order to calm her nerves. Three women named Anne appear, and each woman consecutively visits the seaside town of Mohang. The first Anne is a successful film director. The second Anne is a married woman secretly in an affair with a Korean man. The third Anne is a divorcee whose husband left her for a Korean woman. A young woman tends to the small hotel by the Mohang foreshore owned by her parents. A certain lifeguard can always be seen wandering up and down the beach that lies nearby. Each Anne stays at this small hotel, receives some assistance from the owner’s daughter, and ventures onto the beach where they meet the lifeguard. Technical Information: Country: South Korea Language: English and Korean w/English subtitles Format: 35mm Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1 Sound Dolby: SRD Running Time: 89 min CREW Written and Directed By Hong Sang-soo Producer ― Kim Kyounghee Cinematography ― Park Hongyeol, Jee Yunejeong Lighting ― Yi Yuiheang Recording ― Yoon Jongmin Editor ― Hahm Sungwon Music ― Jeong Yongjin Sound ― Kim Mir CAST Anne ― Isabelle Huppert Lifeguard ― Yu Junsang Womu ― Jung Yumi Park Sook ― Youn Yuhjang Jongsoo ― Kwon Hyehyo Kumhee ― Moon Sori A Kino Lorber Release HONG SANG-SOO Biography Hong Sang-soo made his astounding debut with his first feature film The Day a Pig Fell Into a Well in 1996. -

Azorín, Los Clásicos Redivivos Y Los Universales Renovados Pascale Peyraga

Azorín, los Clásicos redivivos y los universales renovados Pascale Peyraga To cite this version: Pascale Peyraga. Azorín, los Clásicos redivivos y los universales renovados. Pascale Peyraga. Azorín, los Clásicos redivivos y los universales renovados, Dec 2011, Pau, Francia. Instituto Alicantino de Cultura Juan Gil-Albert, pp.285, 2013, Colección Colectiva, 978-84-7784-635-2. hal-01285823 HAL Id: hal-01285823 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01285823 Submitted on 31 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Λ Los Clásicos redivivos y Γ\μ V F L Γ L [os universales renovados Pascale PEYRAGA (dir.) AZORÍN r LOS CLASICOS REDIVIVOS Y LOS UNIVERSALES RENOVADOS VIII Coloquio Internacional Pau, 1-3 de diciembre 2011 Organizado por: Laboratoire de Recherches: Langues, Littératures et Civilisations de l’Arc Atlantique (E.A. 1925), Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour Casa-Museo Azorín, Obra Social de la Caja de Ahorros del Mediterráneo ál DIPUTACIÓN DE ALICANTE Comité de lectura: Rocío Charques Gámez Christelle Colin Emilie Guyard IsabelIbáfiez Nejma Kermele Sophie Torres © De la obra en su conjunto: Laboratoire de Recherches: Langues, Littératures et Civilisations de l’Arc Atlantique (Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour). -

O Exemplo Da Tradução Da Literatura Catalã Em Portugal

https://doi.org/10.22409/gragoata.v24i49.34156 Intersecção entre os Estudos Ibéricos e os Estudos de Tradução: o exemplo da tradução da literatura catalã em Portugal Esther Gimeno Ugaldea Resumo Tomando como ponto de partida a intersecção entre os Estudos Ibéricos e os Estudos de Tradução, este artigo aborda as relações entre os sistemas literários catalão e português com base no trabalho de tradução, nomeadamente da tradução de romances escritos em catalão para português europeu no século XXI. O propósito da análise é duplo: por um lado, e partindo da tradução literária, quer-se salientar a natureza rizomática do espaço ibérico, tal como propõe o paradigma dos Estudos Ibéricos e, por outro, pretende-se mostrar o potencial da intersecção de duas disciplinas que se encontram em expansão. Apresenta-se primeiro uma breve descrição e análise do corpus estudado para depois se centrar no papel intermediário do espanhol. A ênfase posta na tradução indireta permite concluir que este processo de transferência cultural acaba por ter efeitos negativos, uma vez que pode implicar a invisibilização da língua e do sistema cultural menorizado. Palavras-chave: Estudos Ibéricos; Estudos de Tradução; literatura catalã; Portugal; tradução indireta. Recebido em: 24/06/2019 Aceito em: 05/08/2019 a Investigadora no Departamento de Línguas e Literaturas Românicas da Universidade de Viena. E-mail: [email protected]. Gragoatá, Niterói, v.24, n. 49, p. 320-342, mai.-ago. 2019 320 Intersecção entre os Estudos Ibéricos e os Estudos de Tradução Como disciplina comparada que explora as inter-relações culturais e literárias no espaço geográfico peninsular sob uma perspetiva policêntrica (PÉREZ ISASI; FERNANDES, 2013; RESINA, 2009; RESINA, 2013), os Estudos Ibéricos abrem a possibilidade de novos olhares para repensar e analisar a tradução literária intrapeninsular. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

Mirada Al Espacio Interior En Temps D'una Espera De Carme Riera

Magdalena Coll Carbonell Mirada al espacio interior en Temps d’una espera de Carme Riera Examining Interior Space in Carme Riera’s Temps d’una espera Magdalena Coll Carbonell World Languages Department Edgewood College, Madison, WI Recibido el 20 de marzo de 2010 Aprobado el 25 de agosto de 2010 Resumen: Carme Riera, en Temps d'una espera, elabora un diálogo con el feto que ya ocupa un espacio en su cuerpo. La narración es una creación dual, simultáneamente se crean los dos, el nuevo ser y el texto. Este trabajo reflexiona sobre el espacio corporal perteneciente exclusivamente a la mujer y el espacio textual. El útero es textualizado y contextualizado en Temps d'una espera en forma de diario epistolar, en relación al tiempo de ocupación limitado. Reivindicar la maternidad como espacio creativo y vía de liberación para la mujer, este es el objetivo de este análisis. Palabras clave: Maternidad y texto. Creatividad. Espacio. Identidad femenina. Summary: In “Temps d’una espera” Carme Riera composes a dialogue with the fetus that inhabits a space within her body. The narrative describes a dual creation, that of the new being, and of the text itself. This work reflects upon both textual space and the space within their bodies that is the exclusive property of women. In Temps d’una espera the uterus is textualized and contextualized in the form of an epistolary diary, in relation to the limited term of fetal occupation. Riera’s reinvocation of motherhood as a creative space and the road to liberation for women is the objective of this analysis. -

Women's and Gender Studies Film Collection (Updated 6/9/2015)

Women's and Gender Studies Film Collection (updated 6/9/2015) TITLE FORMAT DURATION DESCRIPTION YEAR CATEGORIES This 1989 video reviews the need for safe, legal, and accessible abortion Abortion/Reproductive Abortion for Survival VHS 40 minutes worldwide, highlighting the lack of access to affordable contraception and 1989 Rights/Childbirth women's desire to limit their family size. An open-minded personal approach to the controversy over breast implant safety. Ultimately, Absolutely Safe is the story of everyday women who find themselves Health Absolutely Safe DVD 83 minutes 2009 and their breasts in the tangled and confusing intersection of health, money, Beauty/Body Images science and beauty. This video describes the war on AIDS in Africa. It explores how the disease cuts across the entire population, affecting men and women of reproductive age and HIV/AIDS AIDS in Africa VHS 52 minutes 1990 their children, striking a continent already wracked by underdevelopment, civil Africa strife and corruption. Amelia Earhart: Queen of A&E biography highlighting the life experiences of Amelia Earhart, who was the Biography VHS 50 minutes 1998 the Air first woman to fly alone across the Atlantic Ocean. Feminist History A film inspired by one of Maya Angelou‘s poems, showing how African-American And Still I Rise VHS 30 minutes women deal with myths of their sexuality and how they suffer historical and 1993 African American contemporary stereotypes by the media. This films reconstructs the arsenic murders in the Hungarian countryside, after the First World War. Over 140 bodies were discovered. The victims, all men, were Domestic Violence Angel Makers DVD 34 minutes 2005 apparently killed by their wives. -

Italia-España, Un Entramado De Relaciones Literarias: La “Escuela De Barcelona”

TESIS DOCTORAL FRANCESCO LUTI Italia-España, un entramado de relaciones literarias: la “Escuela de Barcelona” DIRECTORA: DOCTORANDO: CARME RIERA GUILERA FRANCESCO LUTI DIRECTORA: CARME RIERA GUILERA DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOGÍA ESPAÑOLA FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BARCELONA 2012 AGRADECIMIENTOS En primer lugar, me gustaría agradecer a mi directora de tesis, Carme Riera, sin ella no hubiera podido realizar esta investigación. Dos agradecimientos especiales: uno, para el Profesor Gaetano Chiappini, alumno predilecto del gran Oreste Macrí, que con su amistad y afecto me ha apoyado y aconsejado a lo largo de la investigación. Y el otro para María Dolores López Martínez, por su ayuda fundamental en la fase de revisión. Agradezco también a Gloria Manghetti, Ilaria Spadolini y Eleonora Pancani del Archivio Contemporaneo “A. Bonsanti” del Gabinetto Vieusseux de Florencia, el “Archivio di Stato de Turín”, Malcolm Einaudi, Pamela Giorgi de la Fondazione Einaudi, la Cátedra Goytisolo de la UAB, todo el Departamento de Filología Española y Josep Maria Castellet. A Josep Maria Castellet, Ramón Buckley, mi hermano Federico Luti, Carina Azevedo, Fabrizio Bagatti, Katherine McGarry, Ana Castro, Giuseppe Iula y a mi madre, Maria, y los muchos otros amigos que me han ‘suportado’ y ‘soportado’ durante estos años de investigación. Esta tesis está dedicada a la memoria de mi tío Giorgio Luti, que me enseñó a amar la literatura por lo que es, y que a la literatura dedicó toda su vida. Dos semanas después de saber que me había sido concedida una beca para esta tesis, fallecía en su ciudad, Florencia. Su magisterio y su afectuoso recuerdo han sido el motor que me ha llevado hasta el punto final de esta investigación. -

Drama Movies

Libraries DRAMA MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 42 DVD-5254 12 DVD-1200 70's DVD-0418 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 8 1/2 DVD-3832 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 8 1/2 c.2 DVD-3832 c.2 127 Hours DVD-8008 8 Mile DVD-1639 1776 DVD-0397 9th Company DVD-1383 1900 DVD-4443 About Schmidt DVD-9630 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 Accused DVD-6182 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 1 Ace in the Hole DVD-9473 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 1 Across the Universe DVD-5997 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adam Bede DVD-7149 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adjustment Bureau DVD-9591 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs 1 Admiral DVD-7558 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs 5 Adventures of Don Juan DVD-2916 25th Hour DVD-2291 Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert DVD-4365 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 Advise and Consent DVD-1514 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 Affair to Remember DVD-1201 3 Women DVD-4850 After Hours DVD-3053 35 Shots of Rum c.2 DVD-4729 c.2 Against All Odds DVD-8241 400 Blows DVD-0336 Age of Consent (Michael Powell) DVD-4779 DVD-8362 Age of Innocence DVD-6179 8/30/2019 Age of Innocence c.2 DVD-6179 c.2 All the King's Men DVD-3291 Agony and the Ecstasy DVD-3308 DVD-9634 Aguirre: The Wrath of God DVD-4816 All the Mornings of the World DVD-1274 Aladin (Bollywood) DVD-6178 All the President's Men DVD-8371 Alexander Nevsky DVD-4983 Amadeus DVD-0099 Alfie DVD-9492 Amar Akbar Anthony DVD-5078 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul DVD-4725 Amarcord DVD-4426 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul c.2 DVD-4725 c.2 Amazing Dr. -

Join Us. 100% Sirena Quality Taste 100% Pole & Line

melbourne february 8–22 march 1–15 playing with cinémathèque marcello contradiction: the indomitable MELBOURNE CINÉMATHÈQUE 2017 SCREENINGS mastroianni, isabelle huppert Wednesdays from 7pm at ACMI Federation Square, Melbourne screenings 20th-century February 8 February 15 February 22 March 1 March 8 March 15 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm Presented by the Melbourne Cinémathèque man WHITE NIGHTS DIVORCE ITALIAN STYLE A SPECIAL DAY LOULOU THE LACEMAKER EVERY MAN FOR HIMSELF and the Australian Centre for the Moving Image. Luchino Visconti (1957) Pietro Germi (1961) Ettore Scola (1977) Maurice Pialat (1980) Claude Goretta (1977) Jean-Luc Godard (1980) Curated by the Melbourne Cinémathèque. 97 mins Unclassified 15+ 105 mins Unclassified 15+* 106 mins M 101 mins M 107 mins M 87 mins Unclassified 18+ Supported by Screen Australia and Film Victoria. Across a five-decade career, Marcello Visconti’s neo-realist influences are The New York Times hailed Germi Scola’s sepia-toned masterwork “For an actress there is no greater gift This work of fearless, self-exculpating Ostensibly a love story, but also a Hailed as his “second first film” after MINI MEMBERSHIP Mastroianni (1924–1996) maintained combined with a dreamlike visual as a master of farce for this tale remains one of the few Italian films than having a camera in front of you.” semi-autobiography is one of Pialat’s character study focusing on behaviour a series of collaborative video works Admission to 3 consecutive nights: a position as one of European cinema’s poetry in this poignant tale of longing of an elegant Sicilian nobleman to truly reckon with pre-World War Isabelle Huppert (1953–) is one of the most painful and revealing films. -

African Women's Empowerment: a Study in Amma Darko's Selected

African women’s empowerment : a study in Amma Darko’s selected novels Koumagnon Alfred Djossou Agboadannon To cite this version: Koumagnon Alfred Djossou Agboadannon. African women’s empowerment : a study in Amma Darko’s selected novels. Linguistics. Université du Maine; Université d’Abomey-Calavi (Bénin), 2018. English. NNT : 2018LEMA3008. tel-02049712 HAL Id: tel-02049712 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02049712 Submitted on 26 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THESE DE DOCTORAT DE LE MANS UNIVERSITE ET DE L’UNIVERSITE D’ABOMEY-CALAVI COMUE UNIVERSITE BRETAGNE LOIRE ÉCOLE DOCTORALE N° 595 ÉCOLE DOCTORALE PLURIDISCIPLINAIRE Arts, Lettres, Langues «Espaces, Cultures et Développement» Spécialité : Littérature africaine anglophone Par Koumagnon Alfred DJOSSOU AGBOADANNON AFRICAN WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT: A STUDY IN AMMA DARKO’S SELECTED NOVELS Thèse présentée et soutenue à l’Université d’Abomey-Calavi, le 17 décembre 2018 Unités de recherche : 3 LAM Le Mans Université et GRAD Université d’Abomey-Calavi Thèse N° : 2018LEMA3008 Rapporteurs avant soutenance : Komla Messan NUBUKPO, Professeur Titulaire / Université de Lomé / TOGO Philip WHYTE, Professeur Titulaire / Université François Rabelais de Tours / FRANCE Laure Clémence CAPO-CHICHI ZANOU, Professeur Titulaire / Université d’Abomey-Calavi/BENIN Composition du Jury : Présidente : Laure Clémence CAPO-CHICHI ZANOU, Professeur Titulaire / Université d’Abomey-Calavi/BENIN Examinateurs : Augustin Y. -

Cultural Frontiers: Women Directors in Post-Revolutionary New Wave Iranian Cinema

CULTURAL FRONTIERS: WOMEN DIRECTORS IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY NEW WAVE IRANIAN CINEMA by Amanda Chan B-Phil International and Area Studies, University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Submitted to the Faculty of The University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelors of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Amanda Chan It was defended on April 8th, 2016 and approved by Dr. Alison Patterson, Lecturer, Department of English and Film Studies Dr. Ellen Bishop, Lecturer, Department of English and Film Studies Dr. Sarah MacMillen, Associate Professor, Departmental of Sociology Thesis Advisor: Dr. Frayda Cohen, Senior Lecturer, Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies ii CULTURAL FRONTIERS: WOMEN DIRECTORS IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY NEW WAVE IRANIAN CINEMA Amanda Chan University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Amanda Chan 2016 iii CULTURAL FRONTIERS: WOMEN DIRECTORS IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY NEW WAVE IRANIAN CINEMA Amanda Chan University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Iranian New Wave Cinema (1969 to present) has risen to international fame, especially in post-revolutionary years, for its social realist themes and contribution to national identity. This film movement boasts a number of successful women directors, whose films have impressed audiences and film festivals worldwide. This study examines the works of three Iranian women directors, Rakhshan Bani-Etemad, Tamineh Milani, and Samira Makhmalbaf, for their films’ social, political, and cultural themes and commentary while also investigating the directors’ techniques in managing censorship codes that regulate their production and content. Importantly, these women directors must also navigate the Islamic Republic’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance’s censorship laws, which dictate that challenging the government’s law or Islamic law is illegal and punishable. -

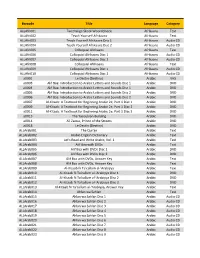

Barcode Title Language Category Allafri001 Tweetalige Skool

Barcode Title Language Category ALLAfri001 Tweetalige Skool-Woordeboek Afrikaans Text ALLAfri002 Teach Yourself Afrikaans Afrikaans Text ALLAfri003 Teach Yourself Afrikaans Disc 1 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri004 Teach Yourself Afrikaans Disc 2 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri005 Colloquial Afrikaans Afrikaans Text ALLAfri006 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 1 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri007 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 2 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri008 Colloquial Afrikaans Afrikaans Text ALLAfri009 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 1 Afrikaans Audio CD ALLAfri010 Colloquial Afrikaans Disc 2 Afrikaans Audio CD a0001 Le Destin (Destiny) Arabic VHS a0003 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 1 Arabic DVD a0004 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 1 Arabic DVD a0005 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 2 Arabic DVD a0006 Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds Disc 2 Arabic DVD a0007 Al-Kitaab: A Textbook for Beginning Arabic 2e, Part 1 Disc 1 Arabic DVD a0009 Al-Kitaab: A Textbook for Beginning Arabic 2e, Part 1 Disc 2 Arabic DVD a0011 Al-Kitaab: A Textbook for Beginning Arabic 2e, Part 1 Disc 3 Arabic DVD a0013 The Yacoubian Building Arabic DVD a0014 Ali Zaoua, Prince of the Streets Arabic DVD a0018 Le Destin (Destiny) Arabic DVD ALLArab001 The Qur'an Arabic Text ALLArab002 Arabic-English Dictionary Arabic Text ALLArab003 Let's Read and Write Arabic, Vol. 1 Arabic Text ALLArab004 Alif Baa with DVDs Arabic Text ALLArab005 Alif Baa with DVDs Disc 1 Arabic DVD ALLArab006 Alif Baa with DVDs Disc 2 Arabic