Called Kang Rimpoche and Is Surrounded by Four Monasteries ; the Lake Is Called Tso Mapang and Is Surrounded by Eight Monasteries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making the State on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier: Chinese Expansion and Local Power in Batang, 1842-1939

Making the State on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier: Chinese Expansion and Local Power in Batang, 1842-1939 William M. Coleman, IV Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2014 © 2013 William M. Coleman, IV All rights reserved Abstract Making the State on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier: Chinese Expansion and Local Power in Batang, 1842-1939 William M. Coleman, IV This dissertation analyzes the process of state building by Qing imperial representatives and Republican state officials in Batang, a predominantly ethnic Tibetan region located in southwestern Sichuan Province. Utilizing Chinese provincial and national level archival materials and Tibetan language works, as well as French and American missionary records and publications, it explores how Chinese state expansion evolved in response to local power and has three primary arguments. First, by the mid-nineteenth century, Batang had developed an identifiable structure of local governance in which native chieftains, monastic leaders, and imperial officials shared power and successfully fostered peace in the region for over a century. Second, the arrival of French missionaries in Batang precipitated a gradual expansion of imperial authority in the region, culminating in radical Qing military intervention that permanently altered local understandings of power. While short-lived, centrally-mandated reforms initiated soon thereafter further integrated Batang into the Qing Empire, thereby -

Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule

TIBET UNDER CHINESE COMMUNIST RULE A COMPILATION OF REFUGEE STATEMENTS 1958-1975 A SERIES OF “EXPERT ON TIBET” PROGRAMS ON RADIO FREE ASIA TIBETAN SERVICE BY WARREN W. SMITH 1 TIBET UNDER CHINESE COMMUNIST RULE A Compilation of Refugee Statements 1958-1975 Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule is a collection of twenty-seven Tibetan refugee statements published by the Information and Publicity Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in 1976. At that time Tibet was closed to the outside world and Chinese propaganda was mostly unchallenged in portraying Tibet as having abolished the former system of feudal serfdom and having achieved democratic reforms and socialist transformation as well as self-rule within the Tibet Autonomous Region. Tibetans were portrayed as happy with the results of their liberation by the Chinese Communist Party and satisfied with their lives under Chinese rule. The contrary accounts of the few Tibetan refugees who managed to escape at that time were generally dismissed as most likely exaggerated due to an assumed bias and their extreme contrast with the version of reality presented by the Chinese and their Tibetan spokespersons. The publication of these very credible Tibetan refugee statements challenged the Chinese version of reality within Tibet and began the shift in international opinion away from the claims of Chinese propaganda and toward the facts as revealed by Tibetan eyewitnesses. As such, the publication of this collection of refugee accounts was an important event in the history of Tibetan exile politics and the international perception of the Tibet issue. The following is a short synopsis of the accounts. -

Chariot of Faith Sekhar Guthog Tsuglag Khang, Drowolung

Chariot of Faith and Nectar for the Ears A Guide to: Sekhar Guthog Tsuglag Khang Drowolung Zang Phug Tagnya Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition 1632 SE 11th Avenue Portland, OR 97214 USA www.fpmt.org © 2014 Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or developed, without permission in writing from the publisher. Set in Goudy Old Style 12/14.5 and BibleScrT. Cover image over Sekhar Guthog by Hugh Richardson, Wikimedia Com- mons. Printed in the USA. Practice Requirements: Anyone may read this text. Chariot of Faith and Nectar for the Ears 3 Chariot of Faith and Nectar for the Ears A Guide to Sekhar Guthog, Tsuglag Khang, Drowolung, Zang Phug, and Tagnya NAMO SARVA BUDDHA BODHISATTVAYA Homage to the buddhas and bodhisattvas! I prostrate to the lineage lamas, upholders of the precious Kagyu, The pioneers of the Vajrayana Vehicle That is the essence of all the teachings of Buddha Shakyamuni. Here I will write briefly the story of the holy place of Sekhar Guthog, together with its holy objects. The Glorious Bhagavan Hevajra manifested as Tombhi Heruka and set innumerable fortunate ones in the state of buddhahood in India. He then took rebirth in a Southern area of Tibet called Aus- picious Five Groups (Tashi Ding-Nga) at Pesar.1 Without discourage- ment, he went to many different parts of India where he met 108 lamas accomplished in study and practice, such as Maitripa and so forth. -

NATIONAL IDENTITY in SCOTTISH and SWISS CHILDRENIS and YDUNG Pedplets BODKS: a CDMPARATIVE STUDY

NATIONAL IDENTITY IN SCOTTISH AND SWISS CHILDRENIS AND YDUNG PEDPLEtS BODKS: A CDMPARATIVE STUDY by Christine Soldan Raid Submitted for the degree of Ph. D* University of Edinburgh July 1985 CP FOR OeOeRo i. TABLE OF CONTENTS PART0N[ paos Preface iv Declaration vi Abstract vii 1, Introduction 1 2, The Overall View 31 3, The Oral Heritage 61 4* The Literary Tradition 90 PARTTW0 S. Comparison of selected pairs of books from as near 1870 and 1970 as proved possible 120 A* Everyday Life S*R, Crock ttp Clan Kellyp Smithp Elder & Cc, (London, 1: 96), 442 pages Oohanna Spyrip Heidi (Gothat 1881 & 1883)9 edition usadq Haidis Lehr- und Wanderjahre and Heidi kann brauchan, was as gelernt hatq ill, Tomi. Ungerar# , Buchklubg Ex Libris (ZOrichp 1980)9 255 and 185 pages Mollie Hunterv A Sound of Chariatst Hamish Hamilton (Londong 197ý), 242 pages Fritz Brunner, Feliy, ill, Klaus Brunnerv Grall Fi7soli (ZGricýt=970). 175 pages Back Summaries 174 Translations into English of passages quoted 182 Notes for SA 189 B. Fantasy 192 George MacDonaldgat týe Back of the North Wind (Londant 1871)t ill* Arthur Hughesp Octopus Books Ltd. (Londong 1979)t 292 pages Onkel Augusta Geschichtenbuch. chosen and adited by Otto von Grayerzf with six pictures by the authorg Verlag von A. Vogel (Winterthurt 1922)p 371 pages ii* page Alison Fel 1# The Grey Dancer, Collins (Londong 1981)q 89 pages Franz Hohlerg Tschipog ill* by Arthur Loosli (Darmstadt und Neuwaid, 1978)9 edition used Fischer Taschenbuchverlagg (Frankfurt a M99 1981)p 142 pages Book Summaries 247 Translations into English of passages quoted 255 Notes for 58 266 " Historical Fiction 271 RA. -

The Lhasa Jokhang – Is the World's Oldest Timber Frame Building in Tibet? André Alexander*

The Lhasa Jokhang – is the world's oldest timber frame building in Tibet? * André Alexander Abstract In questo articolo sono presentati i risultati di un’indagine condotta sul più antico tempio buddista del Tibet, il Lhasa Jokhang, fondato nel 639 (circa). L’edificio, nonostante l’iscrizione nella World Heritage List dell’UNESCO, ha subito diversi abusi a causa dei rifacimenti urbanistici degli ultimi anni. The Buddhist temple known to the Tibetans today as Lhasa Tsuklakhang, to the Chinese as Dajiao-si and to the English-speaking world as the Lhasa Jokhang, represents a key element in Tibetan history. Its foundation falls in the dynamic period of the first half of the seventh century AD that saw the consolidation of the Tibetan empire and the earliest documented formation of Tibetan culture and society, as expressed through the introduction of Buddhism, the creation of written script based on Indian scripts and the establishment of a law code. In the Tibetan cultural and religious tradition, the Jokhang temple's importance has been continuously celebrated soon after its foundation. The temple also gave name and raison d'etre to the city of Lhasa (“place of the Gods") The paper attempts to show that the seventh century core of the Lhasa Jokhang has survived virtually unaltered for 13 centuries. Furthermore, this core building assumes highly significant importance for the fact that it represents authentic pan-Indian temple construction technologies that have survived in Indian cultural regions only as archaeological remains or rock-carved copies. 1. Introduction – context of the archaeological research The research presented in this paper has been made possible under a cooperation between the Lhasa City Cultural Relics Bureau and the German NGO, Tibet Heritage Fund (THF). -

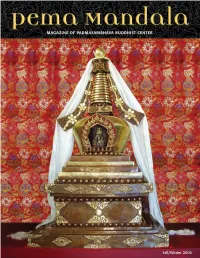

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

Buddhist Ethics in Japan and Tibet: a Comparative Study of the Adoption of Bodhisattva and Pratimoksa Precepts

University of San Diego Digital USD Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship Department of Theology and Religious Studies 1994 Buddhist Ethics in Japan and Tibet: A Comparative Study of the Adoption of Bodhisattva and Pratimoksa Precepts Karma Lekshe Tsomo PhD University of San Diego, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Digital USD Citation Tsomo, Karma Lekshe PhD, "Buddhist Ethics in Japan and Tibet: A Comparative Study of the Adoption of Bodhisattva and Pratimoksa Precepts" (1994). Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship. 18. https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty/18 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Buddhist Behavioral Codes and the Modern World An Internationa] Symposium Edited by Charles Weihsun Fu and Sandra A. Wawrytko Buddhist Behavioral Codes and the Modern World Recent Titles in Contributions to the Study of Religion Buddhist Behavioral Cross, Crescent, and Sword: The Justification and Limitation of War in Western and Islamic Tradition Codes and the James Turner Johnson and John Kelsay, editors The Star of Return: Judaism after the Holocaust -

17-Point Agreement of 1951 by Song Liming

FACTS ABOUT THE 17-POINT “Agreement’’ Between Tibet and China Dharamsala, 22 May 22 DIIR PUBLICATIONS The signed articles in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the Central Tibetan Administration. This report is compiled and published by the Department of Information and International Relations, Central Tibetan Administration, Gangchen Kyishong, Dharamsala 176 215, H. P., INDIA Email: [email protected] Website: www.tibet.net and ww.tibet.com CONTENTS Part One—Historical Facts 17-point “Agreement”: The full story as revealed by the Tibetans and Chinese who were involved Part Two—Scholars’ Viewpoint Reflections on the 17-point Agreement of 1951 by Song Liming The “17-point Agreement”: Context and Consequences by Claude Arpi The Relevance of the 17-point Agreement Today by Michael van Walt van Praag Tibetan Tragedy Began with a Farce by Cao Changqing Appendix The Text of the 17-point Agreement along with the reproduction of the original Tibetan document as released by the Chinese government His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s Press Statements on the “Agreement” FORWARD 23 May 2001 marks the 50th anniversary of the signing of the 17-point Agreement between Tibet and China. This controversial document, forced upon an unwilling but helpless Tibetan government, compelled Tibet to co-exist with a resurgent communist China. The People’s Republic of China will once again flaunt this dubious legal instrument, the only one China signed with a “minority” people, to continue to legitimise its claim on the vast, resource-rich Tibetan tableland. China will use the anniversary to showcase its achievements in Tibet to justify its continued occupation of the Tibetan Plateau. -

OLD FLORIDA BOOK SHOP, INC. Rare Books, Antique Maps and Vintage Magazines Since 1978

William Chrisant & Sons' OLD FLORIDA BOOK SHOP, INC. Rare books, antique maps and vintage magazines since 1978. FABA, ABAA & ILAB Facebook | Twitter | Instagram oldfloridabookshop.com Catalogue of Sanskrit & related studies, primarily from the estate of Columbia & U. Pennsylvania Professor Royal W. Weiler. Please direct inquiries to [email protected] We accept major credit cards, checks and wire transfers*. Institutions billed upon request. We ship and insure all items through USPS Priority Mail. Postage varies by weight with a $10 threshold. William Chrisant & Sons' Old Florida Book Shop, Inc. Bank of America domestic wire routing number: 026 009 593 to account: 8981 0117 0656 International (SWIFT): BofAUS3N to account 8981 0117 0656 1. Travels from India to England Comprehending a Visit to the Burman Empire and Journey through Persia, Asia Minor, European Turkey, &c. James Edward Alexander. London: Parbury, Allen, and Co., 1827. 1st Edition. xv, [2], 301 pp. Wide margins; 2 maps; 14 lithographic plates 5 of which are hand-colored. Late nineteenth century rebacking in matching mauve morocco with wide cloth to gutters & gouge to front cover. Marbled edges and endpapers. A handsome copy in a sturdy binding. Bound without half title & errata. 4to (8.75 x 10.8 inches). 3168. $1,650.00 2. L'Inde. Maurice Percheron et M.-R. Percheron Teston. Paris: Fernand Nathan, 1947. 160 pp. Half red morocco over grey marbled paper. Gilt particulars to spine; gilt decorations and pronounced raised bands to spine. Decorative endpapers. Two stamps to rear pastedown, otherwise, a nice clean copy without further markings. 8vo. 3717. $60.00 3. -

History and Heritage, Vol

Proceeding of the International Conference on Archaeology, History and Heritage, Vol. 1, 2019, pp. 1-11 Copyright © 2019 TIIKM ISSN 2651-0243online DOI: https://doi.org/10.17501/26510243.2019.1101 HISTORY AND HERITAGE: EXAMINING THEIR INTERPLAY IN INDIA Swetabja Mallik Department of Ancient Indian History and Culture, University of Calcutta, India Abstract: The study of history tends to get complex day by day. History and Heritage serves as a country's identity and are inextricable from each other. Simply speaking, while 'history' concerns itself with the study of past events of humans; 'heritage' refers to the traditions and buildings inherited by us from the remote past. However, they are not as simple as it seems to be. The question on historical consciousness and subsequently the preservation of heritage, intangible or living, remains a critical issue. There has always remained a major gap between the historians or professional academics on one hand, and the general public on the other hand regarding the understanding of history and importance of heritage structures. This paper tends to examine the nature of laws passed in Indian history right from the Treasure Trove Act of 1878 till AMASR Amendment Bill of 2017 and its effects with respect to heritage management. It also analyses the sites of Sanchi, Bodh Gaya, and Bharhut Stupa in this context. Moreover, the need and role of the museums has to be considered. The truth lies in the fact that artefacts and traditions both display 'connected histories'; and that the workings of archaeology, history, and heritage studies together is responsible for the continuing dialogue between past, present, and future. -

SYMPOSIUM Moving Borders: Tibet in Interaction with Its Neighbors

SYMPOSIUM Moving Borders: Tibet in Interaction with Its Neighbors Symposium participants and abstracts: Karl Debreczeny is Senior Curator of Collections and Research at the Rubin Museum of Art. He completed his PhD in Art History at the University of Chicago in 2007. He was a Fulbright‐Hays Fellow (2003–2004) and a National Gallery of Art CASVA Ittleson Fellow (2004–2006). His research focuses on exchanges between Tibetan and Chinese artistic traditions. His publications include The Tenth Karmapa and Tibet’s Turbulent Seventeenth Century (ed. with Tuttle, 2016); The All‐Knowing Buddha: A Secret Guide (with Pakhoutova, Luczanits, and van Alphen, 2014); Situ Panchen: Creation and Cultural Engagement in Eighteenth‐Century Tibet (ed., 2013); The Black Hat Eccentric: Artistic Visions of the Tenth Karmapa (2012); and Wutaishan: Pilgrimage to Five Peak Mountain (2011). His current projects include an exhibition which explores the intersection of politics, religion, and art in Tibetan Buddhism across ethnicities and empires from the seventh to nineteenth century. Art, Politics, and Tibet’s Eastern Neighbors Tibetan Buddhism’s dynamic political role was a major catalyst in moving the religion beyond Tibet’s borders east to its Tangut, Mongol, Chinese, and Manchu neighbors. Tibetan Buddhism was especially attractive to conquest dynasties as it offered both a legitimizing model of universal sacral kingship that transcended ethnic and clan divisions—which could unite disparate people—and also promised esoteric means to physical power (ritual magic) that could be harnessed to expand empires. By the twelfth century Tibetan masters became renowned across northern Asia as bestowers of this anointed rule and occult power. -

Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Revised Edition

REVISED EDITION John Powers ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 1 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 2 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 3 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism revised edition by John Powers Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york • boulder, colorado ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 4 Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 • Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 • www.snowlionpub.com © 1995, 2007 by John Powers All rights reserved. First edition 1995 Second edition 2007 No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. Designed and typeset by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Powers, John, 1957- Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism / by John Powers. — Rev. ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-55939-282-2 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-55939-282-7 (alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—China—Tibet. 2. Tibet (China)—Religion. I. Title. BQ7604.P69 2007 294.3’923—dc22 2007019309 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 5 Table of Contents Preface 11 Technical Note 17 Introduction 21 Part One: The Indian Background 1. Buddhism in India 31 The Buddha 31 The Buddha’s Life and Lives 34 Epilogue 56 2. Some Important Buddhist Doctrines 63 Cyclic Existence 63 Appearance and Reality 71 3. Meditation 81 The Role of Meditation in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism 81 Stabilizing and Analytical Meditation 85 The Five Buddhist Paths 91 4.