First Not Last: a Not-So-Modest Proposal to Support First-Generation, Low-Income Students at the University of Pennsylvania" (2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valedictorian Salutatorian James Glazar Ashley Myers

SENIOR ACCEPTANCES AND PLANS Valedictorian Salutatorian James Glazar Ashley Myers Dominic Adelizzi Joseph Berardi Jade Broussard *Kean University *Cabrini College *Saint Joseph’s University Alvernia University Kutztown University Alvernia University Immaculata University Cabrini College +Tyler Berglund Immaculata University Robert M. Allegra III *Saint Joseph’s University La Salle University *Rowan University University of Delaware Rowan College at Gloucester County Angela Antonini Joseph K. Bobiak Jr. Widener University *Rowan University *Virginia Wesleyan College Clare Brown Brooke-Linh Aquilino Maura Bobrek *Montclair State University *Saint Joseph’s University *Rowan College at Gloucester Immaculata University Monmouth University County Monmouth University Mount St. Mary’s University Rutgers, The State University of Mount St. Mary’s University New Jersey St. Francis College Robert Aquilino Widener University *Rowan College at Gloucester +Katherine Bogan County *Villanova University Joseph Robert Brown Liberty University Loyola University Maryland *Prince George’s County Robert Morris University Quinnipiac University Community College University of Maryland University of Connecticut University of North Carolina Michael Buonanno Brian Earl Raymond Bohrer *Rutgers, The State University of +William Asterino III *Rowan College at Gloucester New Jersey *Saint Joseph’s University County Chestnut Hill College University of Delaware Rider University Alexa Bonomo Danielle N. Baxter *Rowan University Isabella Carmela Cammarata *Gwynedd-Mercy -

The Emeritimes the Semester Calendar

President’s Message The winds of change continue to blow briskly at Cal State LA. With fall comes the return of The Emeritimes the semester calendar. The downtown campus Publication of The Emeriti Association California State University, Los Angeles is flourishing. Student en- rollments have reached an Volume XXXVIII, Number 1 Fall 2016 all-time high. We have a new logo (with accompany- ing new bookstore clothing Raphael J. Sonenshein to Speak at Luncheon line), a new athletic direc- tor (dedicated to achieving on This Election Season’s “Wild Ride” Division I status in some Raphael J. Sonenshein, executive director Previously, Sonenshein served as execu- sports), free off-site parking of the Edmund G. “Pat” Brown Institute at Cal tive director of the Los Angeles Appointed (for the first 200 students State LA, will be the featured guest speaker at Charter Reform Commission. The commission to request it), a robust de- the emeriti fall luncheon on Friday, September helped create a unified charter proposal for velopment office (securing major single-donor the ballot that provided the first successful contributions), various administrative changes and comprehensive update to the city’s 1925 (both in personnel and organization), an online scholarship application and review process (work in progress), and 52 new faculty hires (with more promised in the year upcoming) to rebuild the sometimes beleaguered professoriate. Fall The Emeriti Association is undergoing some LUNCHEON transformation as well. At the annual meeting FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 2016 portion of the spring luncheon, the body elected 11:30 A.M. TO 3:00 P.M. Kathy Reilly as secretary and re-elected Rose- See PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE, Page 2 GOLDEN EAglE BAllROOM 1 COST: $37 PER PERSON Send a check made payable to the SEMESTERS!! Emeriti Association, along with your entrée choice: chicken piccata, grilled The first fall semester in 49 years began Affairs Public .Courtesy of Cal State LA at Cal State LA on August 22. -

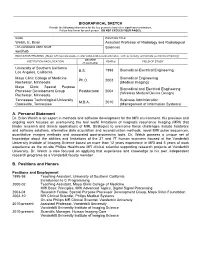

A. Personal Statement B. Positions and Honors

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Provide the following information for the key personnel and other significant contributors. Follow this format for each person. DO NOT EXCEED FOUR PAGES. NAME POSITION TITLE Welch, E. Brian Assistant Professor of Radiology and Radiological eRA COMMONS USER NAME Sciences welcheb EDUCATION/TRAINING (Begin with baccalaureate or other initial professional education, such as nursing, and include postdoctoral training.) DEGREE INSTITUTION AND LOCATION YEAR(s) FIELD OF STUDY (if applicable) University of Southern California 1998 Biomedical-Electrical Engineering Los Angeles, California B.S. Mayo Clinic College of Medicine Biomedical Engineering Ph.D. 2003 Rochester, Minnesota (Medical Imaging) Mayo Clinic Special Purpose Biomedical and Electrical Engineering Processor Development Group Postdoctoral 2004 (Wireless Medical Device Design) Rochester, Minnesota Tennessee Technological University Business Administration M.B.A. 2010 Cookeville, Tennessee (Management of Information Systems) A. Personal Statement Dr. Brian Welch is an expert in methods and software development for the MRI environment. His previous and ongoing work focuses on overcoming the real world limitations of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that hinder research and clinical applications of MRI. Strategies to overcome these challenges include hardware and software solutions, alternative data acquisition and reconstruction methods, novel MRI pulse sequences, quantitative imaging methods and associated post-processing tools. Dr. Welch possess a unique set of knowledge about the abilities and limitations of the 3T and 7T human scanners housed at the Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science based on more than 12 years experience in MRI and 5 years of work experience as the on-site Philips Healthcare MR clinical scientist supporting research projects at Vanderbilt University. -

Scholastic Achievement Awards Ceremony Program 2020.Pub

Ulster County Scholastic Achievement Awards Ceremony A Virtual Celebration June 22, 2020 Sponsored By Ulster County Superintendents’ Council The Award What is the purpose of the Award? The Scholastic Achievement Award is intended to honor outstanding scholastic achievement by members of the graduating classes of the public schools in the Ulster County supervisory district of Ulster BOCES. How are students selected to receive the Award? Student representatives are chosen on the basis of scholarship. The class valedictorian, salutatorian, and one outstanding student selected by the High School Principal are honored. How is this Award Sponsored? The Scholastic Achievement Award program is sponsored and organized by the Ulster County Superintendents’ Council. Honored Students Lauren Anderson (HVPA) Ellery Loheide (Onteora) Quinn Avery (Ellenville) Muhammad Kashan Mahmood (Kingston) Ishani Bansal (Highland) David Mano (HVPA) Grace Barnum (Rondout Valley) Nicole Peters (Saugerties) Conor Bready (Wallkill) Kaitlyn Ronk (CTE) Marysol Calixto (HVPA) Emily Salem (Onteora) Andrew Conklin (Wallkill) Jasmine Shiffer (Ellenville) Mark Danza (Saugerties) Jacob Stern (Onteora) Stephen Dong (Kingston) Alayna Stickles (Ellenville) Isabella Fiorese (Highland) Minh Tran (Highland) Natalia Garcia-Perez (Wallkill) Grace Tremper (Kingston) Lara Goldstein (Rondout Valley) Carter Vail (Saugerties) Landon Haight (CTE) Andrew Westervelt (CTE) Isaiah Jones (Rondout Valley) Wells Willett (New Paltz) Philip Ryan Kelso (New Paltz) Emily Wong-Pan (New Paltz) Ellenville -

Andover High School Celebrates the Class of 2020 AHS Acknowledges Valedictorian, Salutatorians and Graduates Committed to Military Service

PHILIP CONRAD, PRINCIPAL ANDOVER HIGH SCHOOL JOHN NORTON, ASSISTANT PRINCIPAL 80 SHAWSHEEN ROAD CAITLIN BROWN, ASSISTANT PRINCIPAL ANDOVER, MASSACHUSETTS SCOTT DARLINGTON, ASSISTANT PRINCIPAL 978-247-5500 AIXA DE KELLEY, DIRECTOR OF GUIDANCE WILLIAM MARTIN, ATHLETIC DIRECTOR For Immediate Release CONTACT: [email protected] June 8, 2020 Andover High School Celebrates the Class of 2020 AHS acknowledges Valedictorian, Salutatorians and Graduates Committed to Military Service Andover, Mass. -- Andover High School Principal Philip Conrad has announced the Class of 2020 students honored as valedictorian, co-salutatorians and those whom have committed to serving in the United States Military. Kush Shah- AHS co-salutatorian David Grossman- AHS valedictorian Henry Chen –AHS co-salutatorian David Grossman earned the achievement as AHS valedictorian for this year. In addition to this accomplishment, David ranked twelfth (12th) in the state for the Massachusetts Mathematics League Award and received certificates of distinction for the MA Association of Math League Finalist and the American Math Contest and AMC winner. David will attend Brown University in the fall. Henry Chen is a co-salutatorian for the AHS Class of 2020 and has received the Trustees of Punchard: Amy & Albert Trow Educational Fund scholarship. Henry will be attending the University of California, Berkeley in the fall. Kush Shah is co-salutatorian and has received the Trustees of Punchard: Nathan Hamblin Scholarship. Kush has earned awards for excellence in AP Chemistry and Honors Physics. Kush will be attending Tufts University in the fall. Logan Harvie Cora McGrath Vianca Villanueva Logan Harvie, Anna Livingstone, Cora McGrath and Vianca Villanueva received the Red, White and Blue graduation honor cord. -

Vmsmr06 Cover

VANDERBILT MAGAZINE Vsummer 2006 Full Throttle Fonda Huizenga has landed two women’s world records for blue marlin fishing. And she’s just getting her feet wet. aalsolso: ROTC in Wartime A PPeaceworker’seaceworker’s Sacrifice FrFrankank & the Commodore V ITAL Every gift counts. Every year. In fact, every gift is vital…and truly makes a difference every day in the life of Vanderbilt. With your participation in the Vanderbilt Fund, you decide what particular area of Vanderbilt you’d like to support. You can choose to give to a specific college or school. Or, you may want to participate in your class Reunion gift or give to a donor society. Whatever matters most to you. Just know that your support to any area, eative Services in any amount, will count greatly toward Vanderbilt’s continued success, every year. anderbilt Cr www.vanderbilt.edu/thevanderbiltfund 1-866-882-FUND Photos by Peyton Hoge and V Contributors e r 2006 issu Interim Editor e John Bloom GayNelle Doll Writer, comedian and actor John Bloom, BA’74—better known umm Art Director and Designer as his alter ego, Joe Bob Briggs—got his start reviewing movies in a newspa- Donna DeVore Pritchett per column that was later picked up by the New York Times Syndicate. He or the S has written for National Lampoon, Rolling Stone, Playboy and the Village Editorial F Arts & Culture Editor Voice. His latest book is Profoundly Erotic: Sexy Movies That Changed History. Bonnie Arant Ertelt, BS’81 He has hosted two shows on cable television, has appeared on some 50 talk shows, and has appeared as a commentator on Comedy Central’s The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. -

OF 2020 College Attendance

1401 Laurel Oak Road EASTERN CAMDEN COUNTY REGIONAL SCHOOL DISTRicT Voorhees, New Jersey 08043 (856) 784-4441 Fax (856) 627-8407 ASTERN EGIONAL IGH CHOOL E R H S www.eccrsd.us VOLUME 10 | ISSUE 1 | FALL 2020 AP Scholar Awards THE CLASS The College Board’s Advanced Placement Program OF 2020 (AP) provides willing and academically prepared College Attendance students with the opportunity to take rigorous The Class of 2020 is Eastern’s 54th Graduating Class. This class has sought and successfully college-level courses while still in high school, and to received admissions to our country’s most prestigious and renowned institutions of higher earn college credit, advanced placement, or both for education. Several of our students will be pursuing careers in our country’s armed services and successful performance on the AP Exams. in professional industry. A special note of congratulations to Valedictorian Sudhish Devadiga, and Salutatorian Jeremy Bender. The College Board recognizes several levels of achievement based on students’ performance on AP American University Kean University Stevens Institute of Technology Exams. Arcadia University Kutztown University of Pennsylvania Stevenson University Arizona State University-Tempe La Salle University Stockton University AT EASTERN Bentley University Loyola Marymount University Susquehanna University Forty-one students were granted the National AP Bloomsburg University of Loyola University Maryland Sussex County College Pennsylvania Scholar Award. These students received scores of Lycoming College Syracuse University Boston College 3 or higher on three or more AP Exams. Marist College Temple University Brandeis University Twenty-nine students were granted the AP Scholar Monmouth University The College of New Jersey Brigham Young University-Idaho with Honor Award. -

Perspee Which Were During Thursday, Friday, Saturday and Mat Is out to Anyone Wishing .!T Part of Monday

IN THIS ISSUE ANNOUNCEMENT: • (n): E\t.-\L. Ngw M~~{,t CO " ~ . ~~If' 10 . n Jon cU~ • J.\ CL- .-\T IONAL Deadlines Are Changed S Ch lll .~ htp ~ W #I rd. announce-d ; £non,oto rae: lb t t: ~ on s from S \,AC\U\ UOn t The Pacifi c Citizen is advl,l11cing its news and . .. C't-l)lSTRICT PNWDC tour to J Il'Pan nt 1 advertising deadlines to Saturday. The pages will be EDC·'M.oC to h('u Ambl5sador made up by Monday evening and the papers printed Sht1Y\oda 3 MPDC to honol' o\lt s tandl n ll Tuesday morning. We shall continue to date the M• .,bet,hlp Publl"Uon: J.p,"", A.,,,I ..n CIIl'N ,,,,,,l, us Wtll!r St., Los AI!'l,I .., C. 9001Z (2131 MA 6·4471 AJA ~ • papers on Friday, which means our readers west of 'ubllsh,d WeeklJ Empl LUI WHk of Ihe V,lt..-~ Clus 'oslltt '"id IL Los A",.I .., Calif, • JACL-C ll t \I ~Tg n dedl ce t~ s the Mississippi will be getting their papers on or Corter. new hall before the actual date of publication. Those in Cali • COLUMNISTS 21 , 1967 Enomoto: E.."lsl to ..• for nia will be getting their PCs on Wednesday and Vol. 65 No.6 FRIDAY, JULY Edit/Bus. Office: MA 6·6936 TEN CENTS Ml$l.oka: Eonomto tn WtlShinston Ktdo: Romantic At aml and Thursday. (Maybe we can pick up some super HosokawR VI$ltors ,market ad specials, Chas.) Matsul: Human Rct a tton ~ Motta: Sn"lall Wor ld This major change in the production schedule is Kum a m o t o~ 'Bout tb,,' Time J:lenry: Kan»."t Shtmasho part of the temporary arrangement with Crossroads, PNW Japan Tour Glma: Tourist Boom LESSON FROM SaloW: We Get Educated where the PC is "guest." With only one Linotype to Ye Ed's: PI\t:adox in Paradise care for the' needs of Crossroads and the commercial invites all CLers typesetting firm, our own schedule had to be altered EVACUATION to fit into the "open" hours 011 that one machine - PORTLAND - The welcome PERSPEe which were during Thursday, Friday, Saturday and mat is out to anyone wishing .!t part of Monday. -

Embracing Diversity Remembering the Past and Looking Toward the Future

vanderbiltnurseFALL 2006 IN THIS ISSUE: GODCHAUX HALL’S REBIRTH 5 I DARE YOU 10 SURVIVING CANCER 22 embracing diversity Remembering the past and looking toward the future DANIEL DUBOIS dean’s note vanderbiltnurse As I write this, I’m in the refurbished living room Editor Kathy Rivers of Godchaux Hall. Our living room, which still contains the glass cabinets for our artifacts, is now an architectural Director of Publications Medical Center News and Public Affairs hallmark for the school. Some of you will remember the Wayne Wood wooden floors which we restored. Frances Edwards (M.S.N. ‘76, B.S.N. ‘53) reminded me that dances also Copy Editor Nancy Humphrey used to be held here! We have been busy and have a lot to share with Design Diana Duren/Corporate Design, Nashville you. After two years, the Godchaux Hall renovations are officially complete. Everyone has moved into their Contributing Writers Tom Cook new offices. The remaining faculty has all vacated the Jessica Ennis basement of Medical Center North and the triple-wide Irene McKirgan trailer, and I am permanently located on the first floor Maria Overstreet of our “new” building. The six floors, plus the base- Photography/Illustration ment, have been completely overhauled and updated to Kats Barry Neil Brake better serve our students, faculty and staff. We have Daniel Dubois included some pictures of the new Godchaux Hall in this issue and encourage you to visit Dana Johnson Ken Orvidas our Web site to see more. Curtis Parker We are moving forward on several projects. We are working closely with the Pan Anne Rayner American Health Organization to take our relationship to the next level of collaboration. -

Gutfreund Dissertation Draft

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Language Education, Race, and the Remaking of American Citizenship in Los Angeles, 1900- 1968 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5zd66224 Author Gutfreund, Zevi Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Language Education, Race, and the Remaking of American Citizenship in Los Angeles, 1900-1968 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Zevi Moses Gutfreund 2013 © Copyright by Zevi Moses Gutfreund 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Language Education, Race, and the Remaking of American Citizenship in Los Angeles, 1900-1968 by Zevi Moses Gutfreund Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Stephen Aron, Chair This dissertation uses language instruction in Los Angeles as a lens through which to explore assimilation, immigration, and what it means to be an American. It draws from sources such as curricular materials, court records, correspondence, blue book exams, and student newspapers in the city of angels’ Anglo, Mexican, and Japanese American communities. They launched language experiments that attracted national attention from 1900 to 1968, the year of the federal Bilingual Education Act and the “Chicano Blowouts” in East Los Angeles. While many scholars have pointed to those events as crucial moments in the origins of the modern -

Fin Wilson: Playing and High School

School/Sports Wednesday, April 29, 2020 Greensburg Record-Herald 9A School district has many notable changes over the years BY CLEVIS JEFFRIES including standard, organizations have STAFF WRITER vocational, compre- increased through the hensive, honors, and years Major changes commonwealth. In early years, there have occurred in our Students with spe- was a string band and Green County schools cial needs are award- orchestra, as well as over the decades. ed a Certificate of At- FFA, Home Econom- From the very be- tainment. ics, Glee Club, Honor ginning, the county Integration of Club and an Annual has gone from two dif- Greensburg High Staff. ferent Boards of Edu- School sports start- Today, there are cation operating the ed in the late 1950’s numerous organiza- schools, Greensburg with Albert Williams tions, including Aca- and Green County, to being the first Afri- demic, Band, Chorus, a consolidated board can American to play FFA, History, Span- in 1950 after the high basketball during the ish, Science, HOSA, school was destroyed 1959-60 season and DECA, Art, Beta, by fire. Paul Wooldridge, a Yearbook and Rotary For many years, member of the 1958 Interact. Green County had nu- regional champion No longer in ex- merous one and two cross country team. istence on the high classroom schools, Myrtle Wynn was school level is a paper serving students in the first African staff (Dragonette), Ju- grades 1-8. American to attend nior-Senior Banquet, With the closing Greensburg High selection of a Sports of those schools, el- School. This occurred Queen, Junior and Se- Photo submitted ementary students beginning the 1956- nior Plays, selection Finis Albert “Fin” Wilson attended classes in 57 school year. -

Freshman Scholarships Guide 2021-2022

GuideGuide to FRESHMEN to SCHOLARSHIPS 2021FRESHMEN - 2022 2SCHOLAR021-2022 SHIPS Welcome to OleMiss Welcome to A University of Mississippi education is a great investment A University of Mississippi education is a great UPDATED 1/12/21 in yourinves future,tment inand your we futur reallye, andwant w toe r shareeally w withant to youshar thee many with y differentou the man optionsy differ toent help op tionsyou pay to help for your Federal and State Aid Options degree.you pa Thisy for guide your degrwill introduceee. This guide you wilto lpotential introduc escholarships youy oumay to qualifypotential for scholarships to reduce your you tuition!may qualif Wey for to Some families may need to consider grants, student and parent offerreduc everythinge your tuition! from academic We offer e merit-basedverything from scholarships loans, or student employment in addition to scholarships to to need-basedacademic merit scholarships.-based scholarships to help meet the cost of attending the university. It’s important need-based scholarships. to understand how all types of financial aid work and what steps you can take now to plan ahead. We recommend that you One key thing about our scholarships is that some complete the FAFSA each year at https://www.fafsa.govhttps://www.fafsa.gov/ for of them have different deadlines. To be considered federal aid eligibility and, if a Mississippi resident, that you also for any scholarship, you must first apply to Ole apply for state financial aid athttps://msfinancialaid.org https://msfinancialaid.org. Please Miss, and then submit the online Special Programs visit finaid.olemiss.edu to review all options in detail and for a & Scholarship Application.