Pulse Nightclub Critical Incident Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ctif News International Association of Fire & Rescue

CTIF Extra News October 2015 NEWS C T I F INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF FIRE & RESCUE Extra Deadly Fire Roars through Romanian Nightclub killing at least 27 people From New York Times OCT. 30, 2015 “Fire tore through a nightclub in Romania on Friday night during a rock concert that promised a dazzling pyrotechnic show, killing at least 27 people and spreading confusion and panic throughout a central neighborhood of Bucharest, the capital, The Associated Press reported. At least 180 people were injured in the fire at the Colectiv nightclub, according to The Associated Press”. 1 CTIF Extra News October 2015 CTIF starts project to support the increase of safety in entertainment facilities “Information about the large fires always draws a lot of interest. This is especially true in the case when fire cause casualties what is unfortunately happening too often. According to available data, fire at Bucharest nightclub killed at least 27 people while another 180 were injured after pyrotechnic display sparked blaze during the rock concert. The media report that there were 300 to 400 people in the club when a fireworks display around the stage set nearby objects alights. It is difficult to judge what has really happened but as it seems there was a problem with evacuation routes, number of occupants and also people didn’t know whether the flame was a part of the scenario or not. Collected data and testimonials remind us on similar fires and events that happened previously. One of the first that came to the memory is the Station Night Club fire that happened 12 years ago. -

Stadium Name City Twitter Handle Team Name Alabama Jordan–Hare

Stadium Name City Twitter Handle Team Name Alabama Jordan–Hare Stadium Auburn @FootballAU Auburn Tigers Talladega Superspeedway Talladega @TalladegaSuperS Bryant–Denny Stadium Tuscaloosa @AlabamaFTBL Crimson Tide Arkansas Donald W. Reynolds Razorback Fayetteville @RazorbackFB Arkansas Razorbacks Stadium, Frank Broyles Field Arizona Phoenix International Raceway Avondale @PhoenixRaceway Jobing.com Arena Glendale @GilaRivArena Arizona Coyotes University of Phoenix Stadium Glendale @UOPXStadium Arizona Cardinals Chase Field Phoenix @DBacks Arizona Diamondbacks US Airways Center Phoenix @USAirwaysCenter Phoenix Suns Sun Devil Stadium, Frank Kush Field Tempe @FootballASU Arizona State Sun Devils California Angel Stadium of Anaheim Anaheim @AngelStadium L.A. Angels of Anaheim Honda Center Anaheim @HondaCenter Anaheim Ducks Auto Club Speedway Fontana @ACSUpdates Dodger Stadium Los Angeles @Dodgers Los Angeles Dodgers Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Los Angeles @USC_Athletics Southern California Los Angeles Clippers Staples Center Los Angeles @StaplesCenter Los Angeles Lakers Los Angeles Kings Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca Monterey @MazdaRaceway Oakland Athletics O.co Coliseum Oakland @OdotcoColiseum Oakland Raiders Oracle Arena Oakland @OracleArena Golden State Warriors Rose Bowl Pasadena @RoseBowlStadium UCLA Bruins Sleep Train Arena Sacramento @SleepTrainArena Sacramento Kings Petco Park San Diego @Padres San Diego Padres Qualcomm Stadium San Diego @Chargers San Diego Chargers AT&T Park San Francisco @ATTParkSF San Francisco Giants Candlestick Park -

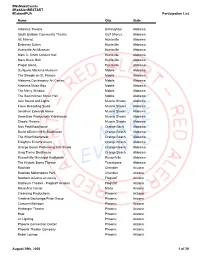

Participation List

#WeMakeEvents #RedAlertRESTART #ExtendPUA Participation List Name City State Alabama Theatre Birmingham Alabama South Baldwin Community Theatre Gulf Shores Alabama AC Marriot Huntsville Alabama Embassy Suites Huntsville Alabama Huntsville Art Museum Huntsville Alabama Mark C. Smith Concert Hall Huntsville Alabama Mars Music Hall Huntsville Alabama Propst Arena Huntsville Alabama Gulfquest Maritime Museum Mobile Alabama The Steeple on St. Francis Mobile Alabama Alabama Contempory Art Center Mobile Alabama Alabama Music Box Mobile Alabama The Merry Window Mobile Alabama The Soul Kitchen Music Hall Mobile Alabama Axis Sound and Lights Muscle Shoals Alabama Fame Recording Sudio Muscle Shoals Alabama Jonathan Edwards Home Muscle Shoals Alabama Sweettree Productions Warehouse Muscle Shoals Alabama Shoals Theatre Muscle Shoals Alabama Nick Pratt Boathouse Orange Bach Alabama David &DeAnn Milly Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama The Wharf Mainstreet Orange Beach Alabama Enlighten Entertainment Orange Beach Alabama Orange Beach Preforming Arts Studio Orange Beach Alabama Greg Trenor Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama Russellville Municipal Auditorium Russellville Alabama The Historic Bama Theatre Tuscaloosa Alabama Rawhide Chandler Arizona Rawhide Motorsports Park Chandler Arizona Northern Arizona university Flagstaff Arizona Orpheum Theater - Flagstaff location Flagstaff Arizona Mesa Arts Center Mesa Arizona Clearwing Productions Phoenix Arizona Creative Backstage/Pride Group Phoenix Arizona Crescent Ballroom Phoenix Arizona Herberger Theatre Phoenix -

Dance 6 Before

And Then We Raved A REVIEW OF THE TBILISI NIGHTCLUB INDUSTRY 2019 TBILISI NIGHTCLUB INDUSTRY Tbilisi Nightclub industry Unlike Tbilisi itself, the city’s nightlife is not able to boast a long history. Yet, the city has achieved recognition as having one of Europe’s best underground scenes. In Georgia, clubbing is about more than just a wild night out. By dismantling stereotypes, Tbilisi underground movement is trying to modify the nation’s stodgy attitudes, which stem from the soviet regime. In this sense, Tbilisi’s clubs can be viewed as islands of free expression. The under- ground culture builds community and gathers like-minded people in one space. The search for new experiences has begun to define numerous sectors, and the nightclub industry is no exception. An unusual and authentic environment is now a crucial part of captivating an audience’s attention. That’s why club owners hunt for places that are guaranteed to create this kind of experience for ravers. In most cases, Tbilisi’s nightclubs are housed in old historical buildings, which adds an additional pull and creates an enigmatic atmosphere for ravers. This practice has been common in the EU for a long time already, especially in Berlin, where former factories and warehouses have been redesigned into clubs. New Trends These days, club owners are integrating the new concept by making night- club spaces available for artistic exhibitions and venues for multifunctional use. Category : c.8,500 80 events Renting price per sq m 10 - 40 GEL “ Tbilisi nightclubs have revived spaces in post-soviet buildings that Capacity per month from USD 2.4 to USD 9 Ticket price went unused for several years.” 02 03 Colliers International Georgia I 2019 TBILISITBILISI NIGHTCLUB HOSTEL INDUSTRY MARKET Nightclubs in Tbilisi Bassiani Khidi Mtkvarze Monohall Located in the underbelly of Dinamo Arena, Bassiani is Khidi, a former industrial space which reopened as a Mtkvarze, a soviet-era seafood restaurant transformed Monohall is a newly opened multifunctional space on renowned as one of the best clubs in Europe. -

POLICE FOUNDATION REPORTS October 1992

POLICE FOUNDATION REPORTS October 1992 Spouse Abuse Research Raises New Questions About Police Response to Domestic Violence Introduction by Hubert Williams President, Police Foundation Of all calls for service to police departments, those for reported spouse everal replications of a study abuse traditionally rank among the most numerous. The magnitude of finding that arrest of spouse the domestic violence problem is wide and deep. Indeed, for all the cases Sassault suspects helped that are reported, it is probable that many more go unreported. prevent repeat assaults have shown mixed results. A number of the For many years, police officers who responded to these calls often felt a replications found no deterrent sense of frustration knowing when they left the scene that they might effect of arrest, while a Police soon have to return to confront again the pain and humiliation of the Foundation replication seems to domestic violence situation. There were no clear answers to handling reinforce the original findings. these cases, no way to assure that the violence would cease. Close examination of the foundation’s research, however, may In recognition of this, the National Institute of Justice funded a Police point to different policy conclusions Foundation study several years ago to see if police treatment of offenders than those suggested by the earlier had an impact on recidivism. The study, conducted in Minneapolis, was study. the first in the history of policing that permitted experimentation with officers’ responses to a situation involving a specific offense. Police That 1984 study, conducted by the Foundation researchers found that arrest of the suspect was more Police Foundation in Minneapolis, effective in deterring future violence than were counseling or sending the found that arrest was a more suspect away from home for several hours. -

Global Nomads: Techno and New Age As Transnational Countercultures

1111 2 Global Nomads 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 A uniquely ‘nomadic ethnography,’ Global Nomads is the first in-depth treat- 3111 ment of a counterculture flourishing in the global gulf stream of new electronic 4 and spiritual developments. D’Andrea’s is an insightful study of expressive indi- vidualism manifested in and through key cosmopolitan sites. This book is an 5 invaluable contribution to the anthropology/sociology of contemporary culture, 6 and presents required reading for students and scholars of new spiritualities, 7 techno-dance culture and globalization. 8 Graham St John, Research Fellow, 9 School of American Research, New Mexico 20111 1 D'Andrea breaks new ground in the scholarship on both globalization and the shaping of subjectivities. And he does so spectacularly, both through his focus 2 on neomadic cultures and a novel theorization. This is a deeply erudite book 3 and it is a lot of fun. 4 Saskia Sassen, Ralph Lewis Professor of Sociology 5 at the University of Chicago, and Centennial Visiting Professor 6 at the London School of Economics. 7 8 Global Nomads is a unique introduction to the globalization of countercultures, 9 a topic largely unknown in and outside academia. Anthony D’Andrea examines 30111 the social life of mobile expatriates who live within a global circuit of counter- 1 cultural practice in paradoxical paradises. 2 Based on nomadic fieldwork across Spain and India, the study analyzes how and why these post-metropolitan subjects reject the homeland to shape an alternative 3 lifestyle. They become artists, therapists, exotic traders and bohemian workers seek- 4 ing to integrate labor, mobility and spirituality within a cosmopolitan culture of 35 expressive individualism. -

Pulse Nightclub Shooting – a Case Study

Jamie Johnson COM 603 Crisis Case Study Pulse Nightclub Shooting – A Case Study Abstract – This article will go into look at the Pulse Nightclub Shooting from the perspective of the Public Information Officer and determine what could have been done better to inform the public at large, the media, and other official agencies that were helping in aiding the Orlando Police Department. During the emergency, a lot of communication was done via social media and while the Orlando Police Department did all they could to control the situation and the message as it was sent out, a lot of things had happened in 6 hours prior to the shooting as well as during the days after the shooting that made their control and management of the crisis a struggle. Within this study, alternative options will be presented to find ways to manage crises like this better in the future. Overview of the Crisis On June 12, 2016, just after last call at 2am, an American born man named Omar Mateen walked into the Pulse Nightclub on Orange Street in Orlando, Florida, armed with a Sig Sauer MCX semi-automatic rifle and a 9mm Glock 17 semi-automatic pistol and started shooting (Wiki, 2017). It was at 2:35am, a half an hour after the shooting began, that the shooter started to make calls to 911, according to the FBI (NPR, 2016). A short time after calling 911, Mateen started to speak to the hostage negotiators with the Orlando Police Department, identifying himself as “an Islamic Soldier” and threatening to detonate explosives – including a car bomb and a suicide vest (NPR, 2016). -

Policing Terrorism

Policing Terrorism A Review of the Evidence Darren Thiel Policing Terrorism A Review of the Evidence Darren Thiel Policing Terrorism A Review of the Evidence Darren Thiel © 2009: The Police Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of The Police Foundation. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Police Foundation. Enquires concerning reproduction should be sent to The Police Foundation at the address below. ISBN: 0 947692 49 5 The Police Foundation First Floor Park Place 12 Lawn Lane London SW8 1UD Tel: 020 7582 3744 www.police-foundation.org.uk Acknowledgements This Review is indebted to the Barrow Cadbury Trust which provided the grant enabling the work to be conducted. The author also wishes to thank the academics, researchers, critics, police officers, security service officials, and civil servants who helped formulate the initial direction and content of this Review, and the staff at the Police Foundation for their help and support throughout. Thanks also to Tahir Abbas, David Bayley, Robert Beckley, Craig Denholm, Martin Innes and Bob Lambert for their insightful, constructive and supportive comments on various drafts of the Review. Any mistakes or inaccuracies are, of course, the author’s own. Darren Thiel, February 2009 Contents PAGE Executive Summary 1 Introduction 5 Chapter -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Amway Center the Orlando Magic Developed the Amway Center, Which Will Compete to Host Major National Events, Concerts and Family Shows

About Amway Center The Orlando Magic developed the Amway Center, which will compete to host major national events, concerts and family shows. The facility opened in the fall of 2010, and is operated by the City of Orlando and owned by the Central Florida community. The Amway Center was designed to reflect the character of the community, meet the goals of the users and build on the legacy of sports and entertainment in Orlando. The building’s exterior features a modern blend of glass and metal materials, along with ever-changing graphics via a monumental wall along one façade. A 180-foot tall tower serves as a beacon amid the downtown skyline. At 875,000 square feet, the new arena is almost triple the size of the old Amway Arena (367,000 square feet). The building features a sustainable, environmentally-friendly design, unmatched technology, featuring 1,100 digital monitors and the tallest, high-definition videoboard in an NBA venue, and multiple premium amenities available to all patrons in the building. Every level of ticket buyer will have access to: the Budweiser Baseline Bar and food court, Club Restaurant, Nutrilite Magic Fan Experience, Orlando Info. Garden, Gentleman Jack Terrace, STUFF’s Magic Castle presented by Club Wyndham and multiple indoor-outdoor spaces which celebrate Florida's climate. Media Kit Table of Contents Enter Legend Public/Private Partnership Fact Sheet By the Numbers Amenities for All Levels Technology LEED: Environmentally-Friendly Corporate Partnerships Jobs in Tough Times Commitment to Parramore Transportation/Parking Concessions Arts and Culture Construction/Design Arena Maps Media Contacts: Joel Glass Heather Allebaugh Tanya Bowley Orlando Magic City of Orlando Amway Center VP/Communications Press Secretary Marketing Manager 407.916-2631 407.246.3423 407.440.7001 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] AmwayCenter.com **For media information: amwaycenter.com/press-room Amway Center: Enter Legend AmwayCenter.com From a vision to blueprints to reality. -

S:\FULLCO~1\HEARIN~1\Committee Print 2018\Henry\Jan. 9 Report

Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. 1 115TH CONGRESS " ! S. PRT. 2d Session COMMITTEE PRINT 115–21 PUTIN’S ASYMMETRIC ASSAULT ON DEMOCRACY IN RUSSIA AND EUROPE: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY A MINORITY STAFF REPORT PREPARED FOR THE USE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JANUARY 10, 2018 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations Available via World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 28–110 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. 9 REPORT FOREI-42327 with DISTILLER seneagle Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS BOB CORKER, Tennessee, Chairman JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland MARCO RUBIO, Florida ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin JEANNE SHAHEEN, New Hampshire JEFF FLAKE, Arizona CHRISTOPHER A. COONS, Delaware CORY GARDNER, Colorado TOM UDALL, New Mexico TODD YOUNG, Indiana CHRISTOPHER MURPHY, Connecticut JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming TIM KAINE, Virginia JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts ROB PORTMAN, Ohio JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon RAND PAUL, Kentucky CORY A. BOOKER, New Jersey TODD WOMACK, Staff Director JESSICA LEWIS, Democratic Staff Director JOHN DUTTON, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. -

Community Policing: a Practical Guide for Police Officials

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Ju\tice Program\ NLIIIOIIN/111$ttffftrof./l(.sftcc pea: September 1989 No. 12 A publication of the National instituteof Justice, U.S. Department of Justice, and the Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management. John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University Community Policing: A Practical Guide for Police Officials By Lee Y. Brown Like many other social institutions, American police depart- ments are responding to rapid social change and emerging This is one in a series of reports originally developed with problems by rethinking their basic strategies. In response to some of the leading figures in American policing during their problems such as crime, drugs, fear, and urban decay, the periodic meetings at Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government. The reportsare published so that police have begun experimenting with new approaches to Americans interested in the improvement and the future of their tasks. policing can share in the information and perspectives that were part of extensivedebates at the School's Executive Among the most prominent new approaches is the concept of Session on Policing. community policing. Viewed from one perspective, it is not a The police chiefs, mayors, scholars,and others invited to the new concept; the principles can be traced back to some of meetings have focused on the use and promise of such policing's oldest traditions. More recently, some of the impor- strategies as community-based and problem-oriented policing. tant principles of community policing have been reflected in The testing and adoption of these strategies by some police particular programs initiated in a variety of places within agencies signal important changes in the way American policing now does business.