Aestimatio: Critical Reviews in the History of Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masarykova Univerzita Filozofická Fakulta Katedra Filozofie Reforma

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Katedra filozofie Reforma vzd ělávání Rogera Bacona Diserta ční práce Vypracoval: Mgr. Josef Šev čík Školitel: prof. PhDr. Břetislav Horyna, Ph.D. Brno 2012 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diserta ční práci vypracoval samostatn ě s využitím uvedených pramen ů a literatury. V Brn ě dne 29. února 2012 ________________ Josef Šev čík Děkuji svému školiteli profesoru B řetislavu Horynovi za odborné vedení a cennou podporu v pr ůběhu doktorského studia, Mgr. Bronislavu Stup ňánkovi za pro čtení disertace, rodi čů m a přátel ům. O B S A H Předmluva................................................................................................................................. 1 I. Úvod ....................................................................................................................................... 4 I.1 Baconovská legenda......................................................................................................... 8 I.2 Hodnota pramen ů a literatury ........................................................................................ 11 I.3 Životní osudy Rogera Bacona........................................................................................ 18 I.4 Opus maius , Opus minus a Opus tertium....................................................................... 32 I.5 Kontext a d ůsledky Tempierova cenzurního výnosu (1277) ......................................... 41 II. Reforma vzd ělávání Rogera Bacona .............................................................................. -

Anatomy of a Dispute: Leonardo, Pacioli, and Scientific Entertainment in Renaissance Milan.', Early Science and Medicine, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer Anatomy of a Dispute Citation for published version: Azzolini, M 2004, 'Anatomy of a Dispute: Leonardo, Pacioli, and Scientific Entertainment in Renaissance Milan.', Early Science and Medicine, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 115 -135. https://doi.org/10.1163/1573382041154088 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1163/1573382041154088 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Early Science and Medicine Publisher Rights Statement: © Azzolini, M. (2004). Anatomy of a Dispute: Leonardo, Pacioli, and Scientific Entertainment in Renaissance Milan.Early Science and Medicine, 9(2), 115 -135doi: 10.1163/1573382041154088 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 anatomy of a dispute 115 ANATOMY OF A DISPUTE: LEONARDO, PACIOLI AND SCIENTIFIC COURTLY ENTERTAINMENT IN RENAISSANCE MILAN* MONICA AZZOLINI University of New South Wales Abstract Historians have recently paid increasing attention to the role of the disputation in Italian universities and humanist circles. By contrast, the role of disputations as forms of entertainment at fifteenth-century Italian courts has been somewhat overlooked. -

The Secrets of Health; Views on Healing from the Everyday Level to the Printing Presses in Early Modern Venice 1500-1650

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts THE SECRETS OF HEALTH; VIEWS ON HEALING FROM THE EVERYDAY LEVEL TO THE PRINTING PRESSES IN EARLY MODERN VENICE 1500-1650 A Dissertation in History by John Gordon Visconti @ 2009 John Gordon Visconti Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 ii The dissertation of John Gordon Visconti was reviewed and approved* by the following: Ronnie Hsia Edwin Earle Sparks Professor of History Dissertation Co-Advisor Chair of Committee A. Gregg Roeber Professor of Early Modern History and Religious Studies Dissertation Co-Advisor Interim Head of the Department of History Tijana Krstic Assistant Professor of Early Modern History Dissertation Co-Advisor Melissa W. Wright Associate Professor in Geography and in the Program of Women's Studies *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii Abstract In early modern Venice, and, to a large extent, the entire European continent, medical practitioners from a wide variety of social levels shared many similar ideas and common assumptions about the body, health, sickness and healing. Ideas regarding moderation in lifestyle, physiological balance within the body, the need to physically eliminate badness from the sick body, and the significance of temperature, moisture and dryness, can be found in healing practices across the social spectrum. The idea that the human body and the heavenly cosmos were divinely linked and that good health depended upon a harmonious relationship with nature can be found at all different social levels of early modern thought. The main reason for these similarities is that ideas about such things, even at the most scholarly levels, were intuitively derived, intellectually plausible, and commonsensical, hence, they occurred to many different people. -

Visualization in Medieval Alchemy

Visualization in Medieval Alchemy by Barbara Obrist 1. Introduction Visualization in medieval alchemy is a relatively late phenomenon. Documents dating from the introduction of alchemy into the Latin West around 1140 up to the mid-thirteenth century are almost devoid of pictorial elements.[1] During the next century and a half, the primary mode of representation remained linguistic and propositional; pictorial forms developed neither rapidly nor in any continuous way. This state of affairs changed in the early fifteenth century when illustrations no longer merely punctuated alchemical texts but were organized into whole series and into synthetic pictorial representations of the principles governing the discipline. The rapidly growing number of illustrations made texts recede to 1 the point where they were reduced to picture labels, as is the case with the Scrowle by the very successful alchemist George Ripley (d. about 1490). The Silent Book (Mutus Liber, La Rochelle, 1677) is entirely composed of pictures. However, medieval alchemical literature was not monolithic. Differing literary genres and types of illustrations coexisted, and texts dealing with the transformation of metals and other substances were indebted to diverging philosophical traditions. Therefore, rather than attempting to establish an exhaustive inventory of visual forms in medieval alchemy or a premature synthesis, the purpose of this article is to sketch major trends in visualization and to exemplify them by their earliest appearance so far known. The notion of visualization includes a large spectrum of possible pictorial forms, both verbal and non-verbal. On the level of verbal expression, all derivations from discursive language may be considered to fall into the category of pictorial representation insofar as the setting apart of groups of linguistic signs corresponds to a specific intention at formalization. -

Download: Brill.Com/Brill-Typeface

The Body of Evidence Medieval and Early Modern Philosophy and Science Editors C.H. Lüthy (Radboud University) P.J.J.M. Bakker (Radboud University) Editorial Consultants Joel Biard (University of Tours) Simo Knuuttila (University of Helsinki) Jürgen Renn (Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science) Theo Verbeek (University of Utrecht) volume 30 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/memps The Body of Evidence Corpses and Proofs in Early Modern European Medicine Edited by Francesco Paolo de Ceglia LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Vesalius dissecting a body in secret. Wellcome Collection. CC BY 4.0. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2019050958 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 2468-6808 ISBN 978-90-04-28481-4 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-28482-1 (e-book) Copyright 2020 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi, Brill Sense, Hotei Publishing, mentis Verlag, Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh and Wilhelm Fink Verlag. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

ARCANA SAPIENZA L’Alchimia Dalle Origini a Jung Michela Pereira Arcana Sapienza L'alchimia Dalle Origini a Jung

Michela Pereira ARCANA SAPIENZA L’alchimia dalle origini a Jung Michela Pereira Arcana sapienza L'alchimia dalle origini a Jung Carocci editore I° edizione, febbraio 2001 © copyright 2001 by Carocci editore S.p.A., Roma Finito di stampare nel febbraio 2001 per i tipi delle Arti Grafiche Editoriali Srl, Urbino ISBN 88-430-1767-5 Riproduzione vietata ai sensi di legge (art. 171 della legge 22 aprile 1941, n. 633) Senza regolare autorizzazione, è vietato riprodurre questo volume anche parzialmente e con qualsiasi mezzo, compresa la fotocopia, anche per uso interno o didattico. Indice Introduzione 13 1. L'origine dell’alchimia: mito e storia nella tradizione occidentale 17 1.1. L’origine dell’alchmiia 17 1.2. Il mito della perfezione 22 1.3. Figli di Ermete 26 2. Segreti della natura e segreti dell'alchimia 31 2.1. I segreti della natura 31 2.2. Preludio all’alchimia 33 2.3. Le dottrine di Ermete 37 2.4. Physikà kaì mystikà 40 3- L’Arte Sacra 47 3.1. In principio la donna 47 3.2. L’altare del sacrificio 51 3.3. Il segreto dell’angelo 55 3.4. Un’acqua divina e filosofica 59 4. 65 4.1. Passaggio ad Oriente 65 7 ARCANA SAPIENZA 4.2. Alchimisti di biblioteca 67 4.3. Il fiore della pratica 69 4.4. La fabbricazione dell’oro 72 5. Cosmologie alchemiche 79 5.1. I segreti della creazione 79 5.2. La Tabula smaragdina 82 5.3. Un congresso di alchimisti 85 5.4. La chiave della sapienza 87 6 . -

The Art of the Distillation of 'Spirits' As a Technological

THE ART OF THE DISTILLATION OF ‘SPIRITS’ AS A TECHNOLOGICAL MODEL FOR HUMAN PHYSIOLOGY. THE CASES OF MARSILIO FICINO, JOSEPH DUCHESNE AND FRANCIS BACON Sergius Kodera Summary This article concerns the role of the distillation apparatus for the production of alcohol in early modern physiological discourses. Here, the still had an amazingly powerful explanatory potential, and this is especially true for the elusive concept of medical spiritus. My text investigates the function of the art of distillation in different authors who were interested in the workings of human, and of celestial, bodies. Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) used the still as an explanatory foil for his Neoplatonist metaphysics, which entailed important and highly influential modi- fications of Aristotelian natural philosophy. In contrast to Ficino’s predominantly theoretical approach, Joseph Duchesne (1546–1609), a French Paracelsian, gives a highly detailed description of the practical aspects of the art of distillation of liquors, which relates to his concept of human physiology. Francis Bacon (1561– 1626) uses a modification of the still to quantify the medical spiritus but also to further elaborate the Paracelsian and the Neoplatonic concepts of physiology. The distillation of ‘spirits’ seems to have been invented at some point dur- ing the twelfth or thirteenth centuries;1 the Florentine Taddeo Alderotti (ca. 1223–1292) called the products generated by the new technology aqua ardens.2 In fourteenth-century Nuremberg, Hausbrand, a kind of brandy made from grapes, was sold cheaply by apothecaries, while distillation 1 On the following, see Multhauf R.P., “Distillation” in Strayer J.R. (ed.), Dictionary of the Middle Ages (New York: 1984), vol. -

'That Senescence Itself Is an Illness': a Transitional Medical Concept of Age and Ageing in the Eighteenth Century

Medical History, 2002, 46: 525-548 'That Senescence Itself is an Illness': A Transitional Medical Concept of Age and Ageing in the Eighteenth Century DANIEL SCHAFER* Senectus ipsa morbus est ... : Jacob Hutter (1708-1768) used this provocative hypo- thesis to draw attention to his doctoral thesis of the same title which was published in 1732 at the University of Halle in Central Germany. Hutter was an otherwise practically unknown figure, who later worked in his native Transylvania as a doctor and pharmacist. His dissertation was reprinted that same year with the title also translated into German: 'That senescence itself is an illness' (Dafl das Alter an und vor sich selbst eine Krankheit seye).' How did Hutter arrive at this striking hypothesis? Did he develop it from his own ideas and possibly also from those of his con- temporaries, or was this aphorism based on older bodies of thought within medicine? The following analysis of Hutter's work in its cultural historical context will show that, around his time, as far as the discussion of old age as an illness was concerned, a long and complex tradition was nearing an end. This tradition can be traced back to ancient times. Surprisingly, the radical claim that old age constitutes an illness had first appeared, not in a medical text, but in a literary work. Hutter, along with other authors around 1700,2 quoted a particular passage from the comedy Phormio by Terence, written about 161 BC. The old Chremes, when asked by his brother Demiphon what illness he was suffering from, replied, "Why do you ask? The illness is old age itself'.3 Lucius Aenaeus Seneca lent further weight to this effective quotation by referring to old age as an incurable illness.4 This paper will demonstrate, however, that this topic had already been treated in a controversial way by the medical works * PD Dr. -

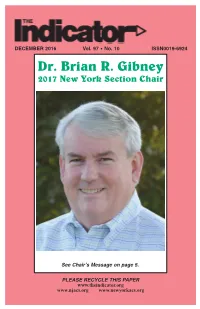

The Indicator-December 2016

DECEMBER 2016 Vol. 97 • No. 10 ISSN0019-6924 Dr. Brian R. Gibney 2017 New York Section Chair See Chairʼs Message on page 5. PLEASE RECYCLE THIS PAPER www.theindicator.org www.njacs.org www.newyorkacs.org 2 THE INDICATOR-DECEMBER 2016 THIS MONTH IN CHEMICAL HISTORY Harold Goldwhite, California State University, Los Angeles • [email protected] In a recent column I drew to your attention a splendid new coffee table book about the history of chemistry. The book is called “The Chemistry Book” by Derek B. Lowe, pub- lished by Sterling in 2016. The title does not describe the book adequately; it could bet- ter be called “The History of Chemistry Book in 250 one page summaries arranged in chronological order from 500,000 BCE to 2030(!)”. The subtitle is “From gunpowder to graphene; 250 milestones in the history of chemistry”. One of the bookʼs most attrac- tive features is that each one page article is accompanied by a full page illustration, mostly in color, relevant to the milestone described. In that column I covered topics from pre-history to the 7th. century. I will now review a few more entries in chronologi- cal order. I recently co-authored a book on “The Chemistry of Alchemy” and so the entry for ca.800 on the philosopherʼs stone caught my eye. It discusses the work of a celebrat- ed Islamic alchemist, probably working in what is today called Iraq. Abu Musa Jabir ibn Hayyan is usually referred to simply as Jabir, and in earlier times his name was Latinized to Geber. -

Estta816047 04/21/2017 in the United States Patent And

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA816047 Filing date: 04/21/2017 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91226939 Party Defendant Conyngham Brewing Company Correspondence LEE ANN PALUBINSKY Address CONYNGHAM BREWING COMPANY PO BOX 1208 CONYNGHAM, PA 18219-0910 UNITED STATES [email protected] Submission Defendant's Notice of Reliance Filer's Name Lee Ann Palubinsky Filer's e-mail [email protected] Signature /Lee Ann Palubinsky/ Date 04/21/2017 Attachments Applicant Notice of Reliance and Exhibits_Part1.pdf(3434975 bytes ) Applicant Notice of Reliance and Exhibits_Part2.pdf(4240583 bytes ) Applicant Notice of Reliance and Exhibits_Part3.pdf(4212347 bytes ) Applicant Notice of Reliance and Exhibits_Part4.pdf(5424027 bytes ) IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD PATRON SPIRITS INTERNATIONAL AG, Opposition No. 91226939 Opposer, Serial No. 86765751 v. Mark: PIRATE PISS CONYNGHAM BREWING COMPANY, Published for Opposition: Applicant February 16, 2016 __________________________________________/ Commissioner for Trademarks PO Box 1451 Alexandria, Virginia 22313-1451 APPLICANT’S NOTICE OF RELIANCE Pursuant to Trademark Rule 2.122(e), 37 C.F.R. §2.122(e), and Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Manual of Procedure Sections 703.02(b) and 708, Applicant Conyngham Brewing Company (“Applicant”) hereby offers into evidence and gives notice that it will rely on the following documents in this proceeding: I. FEDERAL REGISTRATIONS 1. U.S. Application Serial Number 86765751 for PIRATE PISS. A true and correct copy of a printout from the Trademark Electronic Search System (“TESS”) database showing the current status and title of Application Serial Number 86765751 as of 4/20/2017 is attached hereto as Exhibit 1. -

Women's Secrets

Page i Women's Secrets Page ii SUNY Series in Medieval Studies Paul E. Szarmach, Editor Page iii Women's Secrets A Translation of PseudoAlbertus Magnus's De Secretis Mulierum with Commentaries Helen Rodnite Lemay State University of New York Press Page iv Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 1992 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address State University of New York Press, State University Plaza, Albany, NY 12246 Production by Susan Geraghty Marketing by Dana Yanulavich Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data De secretis mulierum. English. Women's secrets : a translation of PseudoAlbertus Magnus' De secretis mulierum with commentaries / Helen Rodnite Lemay. p. cm. Sometimes attributed to Albertus Magnus. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0791411435 (alk. paper) : $49.50. — ISBN 0791411443 (pbk. : alk. paper) : $16.95 1. Medicine, Medieval. 2. Medicine, Magic, mystic, and spagiric—Early works to 1800. I. Lemay, Helen Rodnite. II. Albertus, Magnus, Saint, 1193–1280. III. Title. R128.S3913 1992 610—dc20 9130690 CIP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Page v For Roslyn Schwartz Page vii Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 Authors, Dates of Composition, and the Text 1 Sources 16 Human Generation 20 Astrology 26 The Secrets of Women 32 De Secretis -

The Politics of Medicine at the Late Medici Court: the Recipe Collection of Anna Maria Luisa De’ Medici (1667 – 1743)

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School November 2018 The Politics of Medicine at the Late Medici Court: The Recipe Collection of Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici (1667 – 1743) Ashley Lynn Buchanan University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Scholar Commons Citation Buchanan, Ashley Lynn, "The Politics of Medicine at the Late Medici Court: The Recipe Collection of Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici (1667 – 1743)" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8106 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Politics of Medicine at the Late Medici Court: The Recipe Collection of Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici (1667 – 1743) by Ashley Lynn Buchanan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Giovanna Benadusi, Ph.D. Anne Koenig, Ph.D. Julia F. Irwin, Ph.D. Phillip Levy, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 2, 2018 Keywords: Recipes, Early Modern Medicine, Global Materia Medica, Eighteenth Century Copyright ©