HISTORICAL PROFILES / Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAUSES of WORLD WAR I Objective: Analyze the Causes of World War I

CAUSES of WORLD WAR I Objective: Analyze the causes of World War I. Do Now: What are some holidays during which people celebrate pride in their national heritage? Causes of World War I - MANIA M ilitarism – policy of building up strong military forces to prepare for war Alliances - agreements between nations to aid and protect one another ationalism – pride in or devotion to one’s Ncountry I mperialism – when one country takes over another country economically and politically Assassination – murder of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand Causes of WWI - Militarism Total Defense Expenditures for the Great Powers [Ger., A-H, It., Fr., Br., Rus.] in millions of £s (British pounds). 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1914 94 130 154 268 289 398 1910-1914 Increase in Defense Expenditures France 10% Britain 13% Russia 39% Germany 73% Causes of WWI - Alliances Triple Entente: Triple Alliance: Great Britain Germany France Austria-Hungary Russia Italy Causes of WWI - Nationalism Causes of WWI - Nationalism Pan-Germanism - movement to unify the people of all German speaking countries Germanic Countries Austria * Luxembourg Belgium Netherlands Denmark Norway Iceland Sweden Germany * Switzerland * Liechtenstein United * Kingdom * = German speaking country Causes of WWI - Nationalism Pan-Slavism - movement to unify all of the Slavic people Imperialism: European conquest of Africa Causes of WWI - Imperialism Causes of WWI - Imperialism The “Spark” Causes of WWI - Assassination Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand visited the city of Sarajevo in Bosnia – a country that was under the control of Austria. Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Duchess Sophie in Sarajevo, Bosnia, on June 28th, 1914. Causes of WWI - Assassination Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife were killed in Bosnia by a Serbian nationalist who believed that Bosnia should belong to Serbia. -

World War I 1914-1918

A Significant War Over 16 million people died in WWI and over 20 million were wounded, totaling over 37 million. There are 317 million people in the United States today. That means, that if the casualties from WWI were applied to the United States today, one in every nine people would be dead or wounded. That is how much of an impact this war had on the world, especially Europe, and why it is important to know and understand. World War I What was the correlation between the Age of Imperialism and the outbreak of World War I? Long Term Causes Militarism- Glorifying Military Power Keeping a large standing army prepared for war Arms race for military technology Long Term Causes Nationalism- Deep Devotion to One’s Nation Competition and Rivalry developed between European nations for territory and markets (Example France and Germany- Alsace-Lorraine) Long Term Causes Imperialism- European competition for colonies Quest for colonies often almost led to war Imperialism led to rivalry and mistrust amongst European nations Long Term Causes Alliance System- Designed to keep peace in Europe, instead pushed continent towards war Many Alliances made in secret By 1907 two major alliances: Triple Alliance and Triple Entente The Two Sides Triple Alliance Triple Entente Germany England Austria-Hungary France Italy Russia Central Powers Allied Powers Germany England, France, Austria-Hungary Russia, United Ottoman Empire States, Italy, Serbia, Belgium, Switzerland Game of Allegiance Did it get confusing trying to keep your allegiances -

Alliance System

Alliance System Triple Alliance Triple Entente How did the nations of Europe find themselves in this situation? In order to answer this question you need to focus on the events that occurred in continental Europe following the end of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. Germany’s role is very important. Historical Context – 1870’s Great Britain had adopted a policy of “Splendid Isolation” – which meant that it had chosen to stay out of the affairs of the nations of continental Europe as long as these nations did nothing to challenge the British status as the dominant global superpower. Traditional Order France – British Enemy #1 Germany – Viewed as friendly state Following the end of the Franco- Prussian War of 1870-71 German unification is complete. Kaiser Wilhelm the First makes the decision to establish Germany as the dominant power in Continental Europe. He will challenge France to do this but has no intentions of challenging Great Britain. Task is given to his most senior advisor – Otto Von Bismarck. Bismarck initiates an elaborate system of alliances aimed at isolating France within the confines of continental Europe. • Dual Alliance – 1879 ( Austria-Hungary ) • Triple Alliance – 1882 (adds Italy ) • Reinsurance Treaty with Russia - 1887 Dual Alliance / Triple Alliance / Reinsurance Treaty These alliances accomplish two things for Germany • Isolates France • Does this without angering Great Britain • Avoids imperialism • No naval challenge Turning Point - 1888 Kaiser Wilhelm 1 dies and is replaced by his “ambitious” son – Wilhelm II. Wilhelm II makes several mistakes Fires Bismarck Allows Reinsurance Treaty with Russia to lapse – causes Russia to turn to France. -

The Alliance System Before 1900

How and why did the Alliance System form? L/O – To understand the key features of the alliance system before 1914 Starter – How was the most powerful nation in Europe? Who was second? What is an Alliance? An alliance is an agreement between one or more states to work together. Alliances usually involve making promises to protect the other country against nations who are not in the alliance. These promises are usually made by the signing of treaties. Why were Alliances made? The aim of forming alliances was to achieve collective security – having alliances with other powerful countries deterred your enemies from attacking you. If a country started a war with one nation it would have to fight all its allies as well. Alliances were often made in reaction to national rivalries – when one country felt threatened by another, it often looked to secure friendships with other nations. By 1900, Europe was full of national rivalries. Why were alliances made? There were two main sources of national rivalries: The creation of Germany in 1871 out of the many smaller Germanic states had been opposed by France, resulting in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71. The Germans invaded France and forced the French to sign a humiliating peace treaty. This meant that France and Germany hated each other. The Ottoman (Turkish) Empire in Eastern Europe was crumbling. Russia sought to take advantage of this to expand west into the Balkans. Austria-Hungary wanted to prevent Russian expansion. National Rivalries A dinner party The Rise of Germany • By 1900, the Great Powers in Europe were beginning to divide themselves into two separate groups. -

1 PARIS 1919: ITALY POSITION PAPER War Experience The

PARIS 1919: ITALY POSITION PAPER War Experience The conflict was a tremendous strain for a society already divided between a prosperous, industrializing north and an agrarian, tradition-bound, and less affluent south. The great promise of genuine unification of the 1860s remained elusive. Italy’s economy had grown only slowly, and Italy’s brief forays into foreign affairs had been quite embarrassing, and in the case of its defeat by the Ethiopians at Aduwa in 1896, downright humiliating. When the First War broke out, Italy was allied to its traditional enemy Austria-Hungary as well as to Germany. Under the terms of the Triple Alliance, however, Italy was only obliged to defend its allies if they were attacked first. The Italians used the fact that Austria-Hungary had declared on Serbia as a reason to remain neutral. In any event, at that early stage, little enthusiasm was present among Italians for entering a conflict that many believed had little to do with their nation’s interest. As the war dragged on, however, an increasing number of liberals, republicans, socialists and nationalists, certainly not mutually exclusive, began arguing for intervention on the Allied side. By 1915, when negotiations with the Allies commenced in this regard, the latter appeared to be doing quite well. In addition, and perhaps more importantly, the Allies were prepared to offer Italy a better deal than the Central Powers. First and foremost, Italy coveted Austro-Hungarian territory. The Allies, for their part, were anxious to break the deadlock of the Western Front by attacking the enemy elsewhere. -

Enjoy Your Visit!!!

declared war on Austria, in alliance with the Papal States and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and attacked the weakened Austria in her Italian possessions. embarked to Sicily to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, ruled by the But Piedmontese Army was defeated by Radetzky; Charles Albert abdicated Bourbons. Garibaldi gathered 1.089 volunteers: they were poorly armed in favor of his son Victor Emmanuel, who signed the peace treaty on 6th with dated muskets and were dressed in a minimalist uniform consisting of August 1849. Austria reoccupied Northern Italy. Sardinia wasn’t able to beat red shirts and grey trousers. On 5th May they seized two steamships, which Austria alone, so it had to look for an alliance with European powers. they renamed Il Piemonte and Il Lombardo, at Quarto, near Genoa. On 11th May they landed at Marsala, on the westernmost point of Sicily; on 15th they Room 8 defeated Neapolitan troops at Calatafimi, than they conquered Palermo on PALAZZO MORIGGIA the 29th , after three days of violent clashes. Following the victory at Milazzo (29th May) they were able to control all the island. The last battle took MUSEO DEL RISORGIMENTO THE DECADE OF PREPARATION 1849-1859 place on 1st October at Volturno, where twenty-one thousand Garibaldini The Decade of Preparation 1849-1859 (Decennio defeated thirty thousand Bourbons soldiers. The feat was a success: Naples di Preparazione) took place during the last years of and Sicily were annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia by a plebiscite. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY HISTORY LABORATORY Risorgimento, ended in 1861 with the proclamation CIVIC HISTORICAL COLLECTION of the Kingdom of Italy, guided by Vittorio Emanuele Room 13-14 II. -

Conflict and Tension 1894 – 1918

Conflict and tension 1894 – 1918 Wider world depth study Revision workbook Acklam Grange History department 60 minutes 4 questions to answer. Total of 44 marks. Q1. This source supports …….How do you know? 4 marks Q2.How useful are sources B and C ……..12 marks Q3. Write an account of a crisis………8 marks Q4.The main reason for………was….How far do you agree? 16 marks + 4 SPaG Author: Mrs G Galloway Name: What you need to know Part One – The causes of the First World War The Alliance system including: The Triple Alliance, the Franco – Russian Alliance and the relations between the Entente powers. The crises in Morocco and the Balkans (1905 – 1912) and their effects on international relations. Britain and the challenges to splendid isolation. Kaiser Wilhelm’s aims in foreign policy, including Weltpolitik. Colonial tensions European rearmament, including the Anglo-German naval race. Slav nationalism and relations between Serbia and Austria- Hungary The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo and its consequences The July crisis Timeline 1870 Franco-Prussian war. France was defeated. Germany as a country was created. Alsace and Lorraine were taken from France. To try and protect Germany from a revenge attack by France Germany entered into an alliance with Austria- Hungary and Italy (Triple Alliance) Early 1900s Anglo-German naval race. 1906 Britain launches the HMS Dreadnought. All countries in Europe also building up their arms 1905 First Moroccan Crisis – led to the humiliation of the Kaiser and the creation of the Triple Entente between Britain, France and Russia. Although not intended as a military alliance Germany felt threatened as it was surrounded by hostile neighbours. -

The Centrality of Prestige in Russian and Austro-Hungarian Foreign Policy, 1904-1914 William Weston Nunn

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Image Is Everything: The Centrality of Prestige in Russian and Austro-Hungarian Foreign Policy, 1904-1914 William Weston Nunn Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IMAGE IS EVERYTHING: THE CENTRALITY OF PRESTIGE IN RUSSIAN AND AUSTRO-HUNGARIAN FOREIGN POLICY, 1904-1914 By WILLIAM WESTON NUNN A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2009 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Weston Nunn defended on July 22, 2009. __________________________________ Jonathan Grant Professor Directing Thesis __________________________________ Peter Garretson Committee Member __________________________________ Michael Creswell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii This thesis is an offering dedicated to the glory of God, the fountain from which flows all truth and knowledge. Sola Dei Gloria. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many important people who have assisted in the completion of this thesis. I first want to express my gratitude to the departments of History and Religion at Presbyterian College, specifically Drs. Richard Heiser and Roy Campbell, FSU alumni who were not only my teachers, but my advisors, Dr. Mike Nelson, Dr. Anita Gustafson, Dr. Bryan Ganaway, Dr. Craig Vondergeest, Dr. Bob Bryant, and Dr. Peter Hobbie, my teacher, confidant, and friend. Thank you all for your investments in me as a person and as a student. -

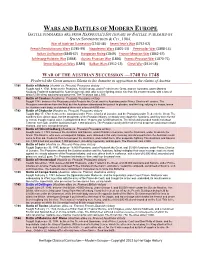

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners. -

Battle of Custoza Newspaper

THE AUSTRIAN DAILY! PAGE1 JULY 26 1848 Batle of Custza Comes t an End. Te batle between te Austian Empire and te Kingdom of Sardinia has reached its brutal end. BACKGROUND: THE CONFLICT ENDS: te nortern Italian region. Te Tis fierce confontaton startd in Earlier tis mont, King Charles defeat of King Charles Albert comes January tis year, when in March Albert led his army across te t no surprise, and he now has been te cit of Milan revoltd against Mincio River, Italy, t engage wit forced by General Radetsky t sign Austian occupaton in what is now General Radetsky’s army. His a peace teat wit Austia. known as te “five days of Milan”. flawed plan, as revealed t te However, even tough tis was a King Charles Albert was in favor of public soon aftrwards, was t spectacular victry for Austia, bot te Milanese revolt, and declared occupy te hiltp and statgic twn sides had major casualtes. More war on Austia. General Radetsky of Custza, for military purposes. tan half of each side’s army was witdrew his toops fom Milan, and Aftr a vicious two-day batle lost, and many are now grieving for focused on seting up stong bases in between te Kingdom of Sardinia te dead. Verona, Mantua, Peschiera, and and te Austian Empire at tis Legnano. Charles Albert ten locaton, General Radetsky has THE QUESTION: strmed Peschiera, and tok it over. emerged victrious, and has taken A queston now remains; wil peace Tis gave him hope tat would soon over Custza terefore driving out be upheld? Or wil tis be yet be lost. -

Triple Alliance (First 8 Articles)

20 May, 1882 The Triple Alliance (First 8 Articles) ARTICLE 1. The High Contracting Parties mutually promise peace and friendship, and will enter into no alliance or engagement directed against any one of their States. They engage to proceed to an exchange of ideas on political and economic questions of a general nature which may arise, and they further promise one another mutual support within the limits of their own interests. ARTICLE 2. In case Italy , without direct provocation on her part , should be attacked by France for any reason whatsoever, the two other Contracting Parties shall be bound to lend help and assistance with all their forces to the Party attacked. This same obligation shall devolve upon Italy in case of any aggression without direct provocation by France against Germany. ARTICLE 3. If one, or two, of the High Contracting Parties, without direct provocation on their part, should chance to be attacked and to be engaged in a war with two or more Great Powers non-signatory to the present Treaty , the casus foederis will arise simultaneously for all the High Contracting Parties. ARTICLE 4. In case a Great Power non-signatory to the present Treaty should threaten the security of the states of one of the High Contracting Parties, and the threatened Party should find itself forced on that account to make war against it, the two others bind themselves to observe towards their Ally a benevolent neutrality. Each of them reserves to itself, in this case, the right to take part in the war, if it should see fit, to make common cause with its Ally. -

Alliances and Power Distribution During the Balkan Quagmire (1912-1913)

Alliances and Power Distribution during the Balkan Quagmire (1912-1913) Zeynep KAYA e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The aim of this paper is to manifest the changing alliance systems at the onset and during the Balkan Wars, as well as to discuss, how the alliance system system contributed to the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire. In order to achieve that goal, a brief introduction to international political system will be provided. It will be noted that the most fertile environment for establishing and maintaining alliances are the bi-polar and multi-polar political systems. The tight alliance systems just before World War I created a multi-polar international system. The multipolar system will be defined and its actors during the time period will be examined. After establishing the theoretical framework of the paper, the second part will provide a brief historical background for the Balkan Wars. The international setting, power structures and the political arena will be dealt with. The next part of the paper will concentrate on interacting alliance structures and their outcomes on the Ottoman Empire. The reason why certain states allied with each other will be discussed. The paper will discuss how alliance formations resulted in first crippling and then eradicating the Ottoman Empire. It is obvious that the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire is a comprehensive and multi-causal process and the Balkan Wars are not the only cause. This paper, will however attempt, to establish the Balkan Wars contributed to the disintegration process and the First World War finalized it. The final part will analyze the outcomes of the alliances and the multipolar international political system.