Palaeoproterozoic Supercontinents and Global Evolution: Correlations from Core to Atmosphere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

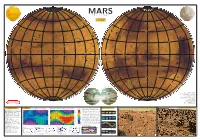

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

Caverns Measureless to Man: Interdisciplinary Planetary Science & Technology Analog Research Underwater Laser Scanner Survey (Quintana Roo, Mexico)

Caverns Measureless to Man: Interdisciplinary Planetary Science & Technology Analog Research Underwater Laser Scanner Survey (Quintana Roo, Mexico) by Stephen Alexander Daire A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the USC Graduate School University of Southern California In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science (Geographic Information Science and Technology) May 2019 Copyright © 2019 by Stephen Daire “History is just a 25,000-year dash from the trees to the starship; and while it’s going on its wild and woolly but it’s only like that, and then you’re in the starship.” – Terence McKenna. Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. xi Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................... xii List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................... xiii Abstract ........................................................................................................................................ xvi Chapter 1 Planetary Sciences, Cave Survey, & Human Evolution................................................. 1 1.1. Topic & Area of Interest: Exploration & Survey ....................................................................12 -

Transactions 1905

THE Royal Astronomical Society of Canada TRANSACTIONS FOR 1905 (INCLUDING SELECTED PAPERS AND PROCEEDINGS) EDITED BY C. A CHANT. TORONTO: ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL PRINT, 1906. The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. THE Royal Astronomical Society of Canada TRANSACTIONS FOR 1905 (INCLUDING SELECTED PAPERS AND PROCEEDINGS) EDITED BY C. A CHANT. TORONTO: ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL PRINT, 1906. TABLE OF CONTENTS. The Dominion Observatory, Ottawa (Frontispiece) List of Officers, Fellows and A ssociates..................... - - 3 Treasurer’s R eport.....................--------- 12 President’s Address and Summary of Work ------ 13 List of Papers and Lectures, 1905 - - - - ..................... 26 The Dominion Observatory at Ottawa - - W. F. King 27 Solar Spots and Magnetic Storms for 1904 Arthur Harvey 35 Stellar Legends of American Indians - - J. C. Hamilton 47 Personal Profit from Astronomical Study - R. Atkinson 51 The Eclipse Expedition to Labrador, August, 1905 A. T. DeLury 57 Gravity Determinations in Labrador - - Louis B. Stewart 70 Magnetic and Meteorological Observations at North-West River, Labrador - - - - R. F. Stupart 97 Plates and Filters for Monochromatic and Three-Color Photography of the Corona J. S. Plaskett 89 Photographing the Sun and Moon with a 5-inch Refracting Telescope . .......................... D. B. Marsh 108 The Astronomy of Tennyson - - - - John A. Paterson 112 Achievements of Nineteenth Century Astronomy , L. H. Graham 125 A Lunar Tide on Lake Huron - - - - W. J. Loudon 131 Contributions...............................................J. Miller Barr I. New Variable Stars - - - - - - - - - - - 141 II. The Variable Star ξ Bootis -------- 143 III. The Colors of Helium Stars - - - ..................... 144 IV. A New Problem in Solar Physics ------ 146 Stellar Classification ------ W. Balfour Musson 151 On the Possibility of Fife in Other Worlds A. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

In Pdf Format

lós 1877 Mik 88 ge N 18 e N i h 80° 80° 80° ll T 80° re ly a o ndae ma p k Pl m os U has ia n anum Boreu bal e C h o A al m re u c K e o re S O a B Bo l y m p i a U n d Planum Es co e ria a l H y n d s p e U 60° e 60° 60° r b o r e a e 60° l l o C MARS · Korolev a i PHOTOMAP d n a c S Lomono a sov i T a t n M 1:320 000 000 i t V s a Per V s n a s l i l epe a s l i t i t a s B o r e a R u 1 cm = 320 km lkin t i t a s B o r e a a A a A l v s l i F e c b a P u o ss i North a s North s Fo d V s a a F s i e i c a a t ssa l vi o l eo Fo i p l ko R e e r e a o an u s a p t il b s em Stokes M ic s T M T P l Kunowski U 40° on a a 40° 40° a n T 40° e n i O Va a t i a LY VI 19 ll ic KI 76 es a As N M curi N G– ra ras- s Planum Acidalia Colles ier 2 + te . -

323455 1 En Bookfrontmatter 1..31

World Geomorphological Landscapes Series editor Piotr Migoń, Wroclaw, Poland More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/10852 Catherine Kuzucuoğlu Attila Çiner • Nizamettin Kazancı Editors Landscapes and Landforms of Turkey 123 Editors Catherine Kuzucuoğlu Nizamettin Kazancı Laboratory of Physical Geography (LGP, Ankara University UMR 8591) Ankara, Turkey CNRS, Universities of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and Paris 12 U-Pec Meudon, France Attila Çiner Istanbul Technical University Istanbul, Turkey ISSN 2213-2090 ISSN 2213-2104 (electronic) World Geomorphological Landscapes ISBN 978-3-030-03513-6 ISBN 978-3-030-03515-0 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03515-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018960303 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Back Matter (PDF)

Index Page numbers in italic denote Figures. Page numbers in bold denote Tables. ‘a’a lava 15, 82, 86 Belgica Rupes 272, 275 Ahsabkab Vallis 80, 81, 82, 83 Beta Regio, Bouguer gravity anomaly Aino Planitia 11, 14, 78, 79, 83 332, 333 Akna Montes 12, 14 Bhumidevi Corona 78, 83–87 Alba Mons 31, 111 Birt crater 378, 381 Alba Patera, flank terraces 185, 197 Blossom Rupes fold-and-thrust belt 4, 274 Albalonga Catena 435, 436–437 age dating 294–309 amors 423 crater counting 296, 297–300, 301, 302 ‘Ancient Thebit’ 377, 378, 388–389 lobate scarps 291, 292, 294–295 anemone 98, 99, 100, 101 strike-slip kinematics 275–277, 278, 284 Angkor Vallis 4,5,6 Bouguer gravity anomaly, Venus 331–332, Annefrank asteroid 427, 428, 433 333, 335 anorthosite, lunar 19–20, 129 Bransfield Rift 339 Antarctic plate 111, 117 Bransfield Strait 173, 174, 175 Aphrodite Terra simple shear zone 174, 178 Bouguer gravity anomaly 332, 333, 335 Bransfield Trough 174, 175–176 shear zones 335–336 Breksta Linea 87, 88, 89, 90 Apollinaris Mons 26,30 Brumalia Tholus 434–437 apollos 423 Arabia, mantle plumes 337, 338, 339–340, 342 calderas Arabia Terra 30 elastic reservoir models 260 arachnoids, Venus 13, 15 strike-slip tectonics 173 Aramaiti Corona 78, 79–83 Deception Island 176, 178–182 Arsia Mons 111, 118, 228 Mars 28,33 Artemis Corona 10, 11 Caloris basin 4,5,6,7,9,59 Ascraeus Mons 111, 118, 119, 205 rough ejecta 5, 59, 60,62 age determination 206 canali, Venus 82 annular graben 198, 199, 205–206, 207 Canary Islands flank terraces 185, 187, 189, 190, 197, 198, 205 lithospheric flexure -

Paleoflooding in the Solar System: Comparison Among Mechanisms For

Paleoflooding in the Solar System: comparison among mechanisms for flood generation on Earth, Mars, and Titan Devon Burr Earth and Planetary Sciences Department EPS 306 University of Tennessee Knoxville 1412 Circle Dr. Knoxville TN 39776-1410 USA [email protected] ABSTRACT Conditions allow surficial liquid flow on three bodies in the Solar System, Earth, Mars, and Titan. Evidence for surficial liquid flood flow has been observed on Earth and Mars. The mechanisms for generating flood flow vary according to the surficial conditions on each body. The most common flood-generating mechanism on Earth is wide-spread glaciation, which requires an atmospheric cycle of a volatile that can assume the solid phase. Volcanism is also a prevalent cause for terrestrial flooding, which other mechanisms producing smaller, though more frequent, floods. On Mars, the mechanism for flood generation has changed over the planet’s history. Surface storage of floodwater early in Mars’ history gave way to subsurface storage as Mars’ climate deteriorated. As on Earth, Mars’ flooding is an effect of the ability of the operative volatile to assume the solid phase, although on Mars, this has occurred in the subsurface. According to this paradigm, Titan conditions preclude extreme flooding because the operative volatile, which is methane, cannot assume the solid phase. Mechanisms that produce smaller but more frequent floods on Earth, namely extreme precipitation events, are likely the most important flood generators on Titan. 1. Introduction The historical flow of paleoflood science has risen and fallen largely in concert with prevailing scientific paradigms (Baker 1998). The paradigm in the 17 th century was catastrophism, the idea that geology is the product of sudden, short, violent events. -

VV D C-A- R 78-03 National Space Science Data Center/ World Data Center a for Rockets and Satellites

VV D C-A- R 78-03 National Space Science Data Center/ World Data Center A For Rockets and Satellites {NASA-TM-79399) LHNAS TRANSI]_INT PHENOMENA N78-301 _7 CATAI_CG (NASA) 109 p HC AO6/MF A01 CSCl 22_ Unc.las G3 5 29842 NSSDC/WDC-A-R&S 78-03 Lunar Transient Phenomena Catalog Winifred Sawtell Cameron July 1978 National Space Science Data Center (NSSDC)/ World Data Center A for Rockets and Satellites (WDC-A-R&S) National Aeronautics and Space Administration Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt) Maryland 20771 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ................................................... 1 SOURCES AND REFERENCES ......................................... 7 APPENDIX REFERENCES ............................................ 9 LUNAR TRANSIENT PHENOMENA .. .................................... 21 iii INTRODUCTION This catalog, which has been in preparation for publishing for many years is being offered as a preliminary one. It was intended to be automated and printed out but this form was going to be delayed for a year or more so the catalog part has been typed instead. Lunar transient phenomena have been observed for almost 1 1/2 millenia, both by the naked eye and telescopic aid. The author has been collecting these reports from the literature and personal communications for the past 17 years. It has resulted in a listing of 1468 reports representing only slight searching of the literature and probably only a fraction of the number of anomalies actually seen. The phenomena are unusual instances of temporary changes seen by observers that they reported in journals, books, and other literature. Therefore, although it seems we may be able to suggest possible aberrations as the causes of some or many of the phenomena it is presumptuous of us to think that these observers, long time students of the moon, were not aware of most of them. -

How Nature Works: the Science of Self-Organized Criticality/ Per Bak

how nature works c Springer Science+Business Media, LLC PERBAK how nature works © 1996 Springer Science+Business Media New York Originally published by Springer-Verlag New York Inc. in 1996 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1996 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. All characters except for historical personages are ficticious. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bak,P. (Per), 194?- How nature works: the science of self-organized criticality/ Per Bak. p. em. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-387-98738-5 ISBN 978-1-4757-5426-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-14757-5426-1 r. Critical phenomena (Physics) 2. Complexity (Philosophy) 3· Physics-Philosophy. I. Title. QC173+C74B34 1996 00 31 .7-dc2o Printed on acid-free paper. Designed by N ikita Pristouris 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 SPIN 10523741 ISBN 978-o-387-98738-5 Who could ever calculate the path of a molecule? How do we know that the creations of worlds are not determined by falling grains of sand? -Victor Hugo, Les M;serables Contents Preface and Acknowledgments Xl Chapter 1 Complex~ty and Cr~t~cal~ty 1 The Laws of Physics Are Simple, but Nature Is Complex . .3 . Storytelling Versus Science . 7. What Can a Theory of Complexity Explain? . 9 Power Laws and Criticality . .27 . Systems in Balance Are Not Complex . .28 . -

Global Catastrophes in Earth History

GLOBAL CATASTROPHES IN EARTH HISTORY An Interdisciplinary Conference on Impacts, Volcanism, and Mass Mortality Snowbird, Utah October 20-23, 1988 N89-2 12E7 --?HEW- Sponsored by The Lunar and Planetary Institute and The National Academy of Sciences Abstracts Presented to the Topical Conference Global Catastrophes in Earth History: An Interdisciplinary Conference on Impacts, Volcanism, and Mass Mortality Snowbird, Utah October 20 - 23,1988 Sponsored by Lunar and Planetary Institute and The National Academy of Sciences LPI Contribution No. 673 Compiled in 1988 Lunar and Planetary Institute Material in this volume may be copied without restraint for library, abstract service, educational, or personal research purposes; however, republication of any paper or portion thereof requires the written permission of the authors as well as appropriate acknowledgment of this publication. PREFACE This volume contains abstracts that have been accepted for presentation at the topical conference Global Catastrophes in Earth History: An Interdisciplinary Conference on Impacts, Volcanism and Mass Mortality. The Organizing Committee consisted of Robert Ginsburg, Chairman, University of Miami; Kevin Burke, Lunar and Planetary Institute; Lee M. Hunt, National Research Council; Digby McLaren, University of Ottawa; Thomas Simkin, National Museum of Natural History; Starley L. Thompson, National Center for Atmospheric Research; Karl K. Turekian, Yale University; George W. Wetherill, Carnegie Institution of Washington. Logistics and administrative support were provided by the Projects Ofice at the Lunar and Planetary Institute. This abstract volume was prepared by the Publications Office staff at the Lunar and Planetary Institute. The Lunar and Planetary Institute is operated by the Universities Space Research Association under contract No. NASW-4066 with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. -

Noah: the Man, the Ark, the Flood

Digging Deeper Links for Noah: The Man, The Ark, The Flood SESSION ONE: NOAH THE MAN The Bible Trumps Everything—Even Creation Science: This article explains the danger of clinging too tightly to models arising from Creation science. It examines some early Creation science models that have given way over the years and discusses the strengths and weaknesses of current models describing the flood. Flood! This article briefly surveys some of the numerous flood accounts in ancient civilizations. Noah’s Flood: the Gilgamesh Epic and Genesis: Some scholars argue Genesis borrowed its flood account from the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh. This article challenges that assertion and provides an alternate view. Living for 900 Years: Today few people reach the age of 120 years. We’re understanding more … but, with new research, can we live longer? Fascinating new information about how and why we age casts fresh light on the long lifespans of pre-flood people. Decreased lifespans: Have we been looking in the right place? This article looks at some possible reasons for the decrease in longevity after the flood. Meeting the Ancestors This article shares a fascinating observation about the patriarchal lists of early Genesis. Extreme Aging Tragically, some children age at tremendous rates, resulting in an average lifespan of thirteen years. SESSION TWO: THE ARK Thinking Outside the Box This webpage takes an in depth look at the ark and how it safely brought Noah, his family, and all those animals through the Flood’s devastation. Where does the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod stand on Genesis 1? This page contains the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod’s official doctrinal position.