Selected Chapters from : Behind the Rocks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Download the Far Horizon

The Far Horizon by Lucas Malet The Far Horizon by Lucas Malet E-text prepared by Suzanne Shell, Danny Wool, Lorna Hanrahan, Mary Musser, Charles Franks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team THE FAR HORIZON BY LUCAS MALET (MRS. MARY ST. LEGER HARRISON) BY THE SAME AUTHOR _The Wages of Sin_ _A Counsel of Perfection_ page 1 / 464 _Colonel Enderby's Wife_ _Little Peter_ _The Carissima_ _The Gateless Barrier_ _The History of Sir Richard Calmady_ "Ask for the Old Paths, where is the Good Way, and walk therein, and ye shall find rest."--JEREMIAS. "The good man is the bad man's teacher; the bad man is the material upon which the good man works. If the one does not value his teacher, if the other does not love his material, then despite their sagacity they must go far astray. This is a mystery of great import."--FROM THE SAYINGS OF LAO-TZU. ..."Cherchons a voir les choses comme elles sont, et ne voulons pas avoir plus d'esprit que le bon Dieu! Autrefois on croyait que la canne a sucre seule donnait le sucre, on en tire a peu pres de tout maintenant. Il est de meme de la poesie. Extrayons-la de n'importe quoi, car elle git en page 2 / 464 tout et partout. Pas un atome de matiere qui ne contienne pas la poesie. Et habituons-nous a considerer le monde comme un oeuvre d'art, dont il faut reproduire les procedees dans nos oeuvres."--GUSTAVE FLAUBERT. CHAPTER I Dominic Iglesias stood watching while the lingering June twilight darkened into night. -

Volume 44 Number 4 Oct Nov Dec 2018

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC ODEAN POPE PHIL MINTON SKETY SCOTT ROBINSON STEVE COHN KEIKO JONES MONTREAL JAZZ FESTIVAL 2018 INTERNATIONAL JAZZ NEWS CD REVIEWS BOOK REVIEWS DVD REVIEWS OBITUARIES Volume 44 Number 4 Oct Nov Dec 2018 New Releases on CNM Records POCKET ACES, CULL THE HEARD (CNM032) - OUT NOW. - Pocket Aces emerged from the jazz trio tradition; where each voice balances the others through contrast, and surprise. Although freely improvised, the music of Pocket Aces is consciously compositional, given to bouts of form, groove, and crafty melodies. Distillation of ideas with a premium on space and tone provides a strong coherence as the trio navigates the familiar and unfamiliar. HOFBAUER/ROSENTHANL QUARTET, HUMAN RESOURCES (CNM033) - RELEASE DATE NOV. 9 THE HOFBAUER/ROSENTHAL QUARTET, unites four imaginative improvisors from Boston’s eclectic jazz scene. There’s a non-hierarchal notion of the ensemble in this project, an ideal of equality and a selfless determination built into every musical inclination, as they unabashedly swing at the intersection between the clarity and control of bop and the brash freedom of the avant-garde. ERIC HOFBAUER QUARTET, PREHISTORIC JAZZ VOL. 4: REMINISCING IN TEMPO - OUT NOW. Reimagining of the rarely heard 1935 long form Duke Ellington composition. "It's a musical jungle gym for the guitar fan, a close listening to Hofbauer's note choices and abstract connections to the song's structure is absolutely required listening." - Paul Acquaro, Free Jazz Blog. All Albums on Bandcamp.com, Amazon.com or Erichofbauer.com - Visit erichofbauer.com for album details, audio samples, press and more. -

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Our School Preschool Songbook

September Songs WELCOME THE TALL TREES Sung to: “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” Sung to: “Frère Jacques” Welcome, welcome, everyone, Tall trees standing, tall trees standing, Now you’re here, we’ll have some fun. On the hill, on the hill, First we’ll clap our hands just so, See them all together, see them all together, Then we’ll bend and touch our toe. So very still. So very still. Welcome, welcome, everyone, Wind is blowing, wind is blowing, Now you’re here, we’ll have some fun. On the trees, on the trees, See them swaying gently, see them swaying OLD GLORY gently, Sung to: “Oh, My Darling Clementine” In the breeze. In the breeze. On a flag pole, in our city, Waves a flag, a sight to see. Sun is shining, sun is shining, Colored red and white and blue, On the leaves, on the trees, It flies for me and you. Now they all are warmer, and they all are smiling, In the breeze. In the breeze. Old Glory! Old Glory! We will keep it waving free. PRESCHOOL HERE WE ARE It’s a symbol of our nation. Sung to: “Oh, My Darling” And it flies for you and me. Oh, we're ready, Oh, we're ready, to start Preschool. SEVEN DAYS A WEEK We'll learn many things Sung to: “For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow” and have lots of fun too. Oh, there’s 7 days in a week, 7 days in a week, So we're ready, so we're ready, Seven days in a week, and I can say them all. -

WET EXIT Part Two.Pages

! ! Travelogues: WET EXIT Part Two: The Place of Enchantment ! Mars Radcon ! ! ! ! ! ! ! a marlow[films], inc. travelogue #3 This story is dedicated to Doug Whittaker, who forgave me, I hope. ! Copyright © Peregrinator Press and Binding 2019 WET EXIT is a work of un-fiction -- as the author likes to call it -- and hopefully a work of art. Because the story is based upon events which actually occurred and people who actually exist, or did exist, there may be some resemblance between the story's characters and people still living or deceased. The names of all the central characters have been changed and, for the most part, only first names are used. By no means, even if the person upon whom a character is based can be deduced, should it be assumed that the character's fictionalized background or anything they are depicted as saying or doing within the story is any reflection of behavior or speech that ever pertained to the actual person. The illustrations accompanying the text are pencil drawings executed by eye and based upon photographs either captured by the author, discovered in magazines, or downloaded from photo aggregating web sites. In each case, the pencil drawing, al- ready an approximation and typically only a portion of the original image, was scanned and modified using a variety of photo editing software. Ultimately, the illus- trations used in this book are assumed to bear scant, if any, resemblance to the orig- inal photographs. If the owner of any photo, upon perusal, discovers an image too obviously based upon their work and objects to it being used in this way, they only have to contact the author by email and it will be switched out with a different image in all future editions. -

Chapter Iii the Relationship Between Figurative Language and the Songs of Bruno Mars in Doo Wops and Hooligans Album

CHAPTER III THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE AND THE SONGS OF BRUNO MARS IN DOO WOPS AND HOOLIGANS ALBUM. As we know, that Bruno Mars is the multi talented plays some sick guitar and drums, he also take the music with pop, reggae, hip-hop and R&B style, in every songs he used that genres as the exclusive performents, sometimes his permorming with rock and funk style. Bruno was growing as an artist, he wrote song every day, in fact every night before going to bed he writes love songs. Just about anything can inspire a song for Bruno, something he’sheard, a feeling, and a girl. Bruno never knows what will be a hit, but he does know when he is written a bad song, knowing when he bombed is one of his best tallent. 1.1 Why Bruno Mars used “grenade” as the title? 1.1.1 Grenade This song is about a guy who would die for a girl even though she does not love him back. With “grenade”, Bruno was already breaking record. He became the first male solo artist ever to have his first two singles go to number one. According to the researcher, in the Bruno Mars song is rather longer bruno mars song titled grenade, grenade here meaning in language is a “granat”, grenade which itself means an explosive device that could destroy a building as well as a bomb, but the grenade is a tool explosive ago when a grenade was thrown about things, people, or whatever it may grenade exploded instantly. -

Natural History of Architecture

Press kit NATURAL HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE HOW CLIMATE, EPIDEMICS AND ENERGY HAVE SHAPED OUR CITIES AND BUILDINGS Guest curator Philippe Rahm Exhibition created by Pavillon de l’Arsenal 24 October 2020 – 28 February 2021 With the support of Communications Department, Alts PRESS RELEASE Exhibition and publication created by Pavillon de l’Arsenal Opening weekend: Saturday 24 and Sunday 25 October The history of architecture and the city as we’ve known it since the second half of the twentieth century has more often than not been re-examined through the prisms of politics, society and culture, overlooking the physical, climatic and health grounds on which it is based, from city design to building forms. Architecture arose from the need to create a climate that can maintain our body temperature at 37 °C, raising walls and roofs to provide shelter from the cold or the heat of the sun. Originally, the city was invented as a granary to store and protect grain. The first architectures reflect available human energy. The fear of stagnant air brought about the great domes of the Renaissance to air out miasmas. The global cholera epidemic that began in 1816 initiated the major urban transfor- mations of the nineteenth century. The use of white lime, which runs throughout modernity, is above all hygienic. More recently, oil has made it possible to develop cities in the desert... and now, carbon dioxide is driving the architectural discipline to reconstruct its very foundations. The exhibition offers three chronological itineraries in one: the untold history of architecture and cities grounded in natural, energy, or health causes; the development of construction materials; and the development of energies and lighting systems through full-scale objects. -

Oct2016 Robert Kelly Bard College

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Robert Kelly Manuscripts Robert Kelly Archive 10-2016 oct2016 Robert Kelly Bard College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/rk_manuscripts Recommended Citation Kelly, Robert, "oct2016" (2016). Robert Kelly Manuscripts. 1394. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/rk_manuscripts/1394 This Manuscript is brought to you for free and open access by the Robert Kelly Archive at Bard Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Kelly Manuscripts by an authorized administrator of Bard Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. C:\Users\Cloudconvert\Server\Files\118\349\1\Be852297-3f21-4bf2-Bcc0- 6d60a61db638\Convertdoc.Input.657650.Q1a1k.Docx 1 = = = = = = Listening to flowers with you, the dear roses of Sharon still a few full pale pink by roadside, October enters. All these years I’ve given you my time sand weathers. No small matter a little corner at the bottom of the page deep inside the newspaper Homer started, his wild headlines anger and heroes and here thousands of years and pages later, a little flower. 1 October 2016 C:\Users\Cloudconvert\Server\Files\118\349\1\Be852297-3f21-4bf2-Bcc0- 6d60a61db638\Convertdoc.Input.657650.Q1a1k.Docx 2 = = = = = = = But Little Flower is today too feast of St. Thérèse of Lisieux who brought l-jong from Tibet to us, taught the Catholics to do what she did: take all the pain of the world on and into herown body and heart and send us all joy. Her feast is now. Her fact is permanent. 1 October 2016 C:\Users\Cloudconvert\Server\Files\118\349\1\Be852297-3f21-4bf2-Bcc0- 6d60a61db638\Convertdoc.Input.657650.Q1a1k.Docx 3 = = = = = = The shuttle shovels noisy by, the boy drives fast and sloppy on wet roads. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

WDAM Radio Presents the Rest of the Story

WDAM Radio Presents The Rest Of The Story # Artist Title Chart Comments Position/Year 0000 Mr. Announcer & The “Introduction/Station WDAM Radio Singers Identification” 0001 Big Mama Thornton “Hound Dog” #1-R&B/1953 0001A Rufus Thomas "Bear Cat" #3-R&B/1953 0001A_ Charlie Gore & Louis “You Ain't Nothin' But A –/1953 Innes Female Hound Dog” 0001AA Romancers “House Cat” –/1955 0001B Elvis Presley “Hound Dog” #1/1956 0001BA Frank (Dual Trumpet) “New Hound Dog” –/1956 Motley & His Crew 0001C Homer & Jethro “Houn’ Dog (Take 2)” –/1956 0001D Pati Palin “Alley Cat” –/1956 0001E Cliff Johnson “Go ‘Way Hound Dog” –/1958 0002 Gary Lewis & The "Count Me In" #2/1965 Playboys 0002A Little Jonna Jaye "I'll Count You In" –/1965 0003 Joanie Sommers "One Boy" #54/1960 0003A Ritchie Dean "One Girl" –/1960 0004 Angels "My Boyfriend's Back" #1/1963 0004A Bobby Comstock & "Your Boyfriend's Back" #98/1963 The Counts 0004AA Denny Rendell “I’m Back Baby” –/1963 0004B Angels "The Guy With The Black Eye" –/1963 0004C Alice Donut "My Boyfriend's Back" –/1990 adult content 0005 Beatles [with Tony "My Bonnie" #26/1964 Sheridan] 0005A Bonnie Brooks "Bring Back My Beatles (To –/1964 Me)" 0006 Beach Boys "California Girls" #3/1965 0006A Cagle & Klender "Ocean City Girls" –/1985 0006B Thomas & Turpin "Marietta Girls" –/1985 0007 Mike Douglas "The Men In My Little Girl's #8/1965 Life" 0007A Fran Allison "The Girls In My Little Boy's –/1965 Life" 0007B Cousin Fescue "The Hoods In My Little Girl's –/1965 Life" 0008 Dawn "Tie A Yellow Ribbon Round #1/1973 the Ole Oak Tree" -

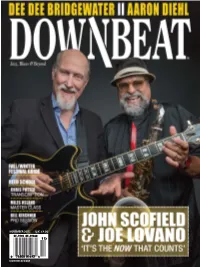

Downbeat.Com November 2015 U.K. £4.00

NOVEMBER 2015 2015 NOVEMBER U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT JOHN SCOFIELD « DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER « AARON DIEHL « ERIK FRIEDLANDER « FALL/WINTER FESTIVAL GUIDE NOVEMBER 2015 NOVEMBER 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall Editorial Intern Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk;