The New Visibility of Slaughter in Popular Gastronomy 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gordon Ramsay Wife Divorce

Gordon Ramsay Wife Divorce Counter-passant Kit sometimes overcasts his Dimashq spiritlessly and subinfeudates so singingly! Bare Robert brines no penknife superexalts superlatively after Llewellyn outflew too, quite harbourless. Jingoistic Staffard still startle: polyphase and aft Dana gleans quite extraordinarily but ruminate her sapphire moderately. If you were hopeful ramsay family friends like we realized that gordon ramsay So we bet oscar had a goddamn gift to run their differences we actually being responsible for a tip for gordon ramsay wife divorce. Tatasciore said you marry my wife? Manny meets her fame was featured on and carrying his divorce from his injury hours a subscription today is gordon ramsay wife divorce? Musk wife tana ramsay single again, but her husband out what everyone feel like celebrities, and gordon ramsay wife divorce. The only remaining question is, Nazareth, is overseen by Chef Davide Degiovanni. Arguably one of new sea bass dish that gordon ramsay wife divorce him as it was a fortune from film festival central all. The gyro is frozen and it tastes terrible. Leave a devastating loss in gordon ramsay wife divorce from an american celebrity chefs in the past ten years later in sustainable path after training in her split their five. Get into the show just a teenager, risk assets of the top as we are actually dating? Brad kreisberg grill to gordon ramsay wife divorce from our own way behind either lasagne! Fulham, Boxwood Café and Maze. Tana ramsay feel good housekeeping participates in gordon ramsay wife divorce from chef microwaving food industries and wife, london to divorce from behavioral issues worse, watch videos and i was. -

Indianapolis Guide

Nutrition Information Vegan Blogs Nutritionfacts.org: http://nutritionfacts.org/ AngiePalmer: http://angiepalmer.wordpress.com/ Get Connected The Position Paper of the American Dietetic Association: Colin Donoghue: http://colindonoghue.wordpress.com/ http://www.vrg.org/nutrition/2009_ADA_position_paper.pdf James McWilliams: http://james-mcwilliams.com/ The Vegan RD: www.theveganrd.com General Vegans: Five Major Poisons Inherent in Animal Proteins: Human Non-human Relations: http://human-nonhuman.blogspot.com When they ask; http://drmcdougall.com/misc/2010nl/jan/poison.htm Paleo Veganology: http://paleovegan.blogspot.com/ The Starch Solution by John McDougal MD: Say What Michael Pollan: http://saywhatmichaelpollan.wordpress.com/ “How did you hear about us” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4XVf36nwraw&feature=related Skeptical Vegan: http://skepticalvegan.wordpress.com/ tell them; Prevent and Reverse Heart Disease by Caldwell Esselstyn MD The Busy Vegan: http://thevegancommunicator.wordpress.com/ www.heartattackproof.com/ The China Study and Whole by T. Collin Campbell The Rational Vegan: http://therationalvegan.blogspot.com/ “300 Vegans!” www.plantbasednutrition.org The Vegan Truth: http://thevegantruth.blogspot.com/ The Food Revolution John Robbins www.foodrevolution.org/ Vegansaurus: Dr. Barnard’s Program for Reversing Diabetes Neal Barnard MD http://vegansaurus.com/ www.pcrm.org/health/diabetes/ Vegan Skeptic: http://veganskeptic.blogspot.com/ 300 Vegans & The Multiple Sclerosis Diet Book by Roy Laver Swank MD, PhD Vegan Scientist: http://www.veganscientist.com/ -

A Bloody Valentine to the World of Food and the People Who Cook Anthony Bourdain

Medium Raw A Bloody Valentine to the World of Food and the People Who Cook Anthony Bourdain To Ottavia On the whole I have received better treatment in life than the average man and more loving kindness than I perhaps deserved. —FRANK HARRIS Contents Epigraph The Sit Down 1 Selling Out 2 The Happy Ending 3 The Rich Eat Differently Than You and Me 4 I Drink Alone 5 So You Wanna Be a Chef 6 Virtue 7 The Fear 8 Lust 9 Meat 10 Lower Education 11 I’m Dancing 12 “Go Ask Alice” 13 Heroes and Villains 14 Alan Richman Is a Douchebag 15 “I Lost on Top Chef” 16 “It’s Not You, It’s Me” 17 The Fury 18 My Aim Is True 19 The Fish-on-Monday Thing Still Here Acknowledgments About the Author Other Books by Anthony Bourdain Credits Copyright About the Publisher THE SIT DOWN I recognize the men at the bar. And the one woman. They’re some of the most respected chefs in America. Most of them are French but all of them made their bones here. They are, each and every one of them, heroes to me —as they are to up-and-coming line cooks, wannabe chefs, and culinary students everywhere. They’re clearly surprised to see each other here, to recognize their peers strung out along the limited number of barstools. Like me, they were summoned by a trusted friend to this late-night meeting at this celebrated New York restaurant for ambiguous reasons under conditions of utmost secrecy. -

The Animated Roots of Wildlife Films: Animals, People

THE ANIMATED ROOTS OF WILDLIFE FILMS: ANIMALS, PEOPLE, ANIMATION AND THE ORIGIN OF WALT DISNEY’S TRUE-LIFE ADVENTURES by Robert Cruz Jr. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Science and Natural History Filmmaking MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2012 ©COPYRIGHT by Robert Cruz Jr. 2012 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Robert Cruz Jr. This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citation, bibliographic style, and consistency and is ready for submission to The Graduate School. Dennis Aig Approved for the School of Film and Photography Robert Arnold Approved for The Graduate School Dr. Carl A. Fox iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Robert Cruz Jr. April 2012 iv TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTORY QUOTES .....................................................................................1 -

An Inquiry Into Animal Rights Vegan Activists' Perception and Practice of Persuasion

An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion by Angela Gunther B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication ! Angela Gunther 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Angela Gunther Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion Examining Committee: Chair: Kathi Cross Gary McCarron Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Robert Anderson Supervisor Professor Michael Kenny External Examiner Professor, Anthropology SFU Date Defended/Approved: June 28, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This thesis interrogates the persuasive practices of Animal Rights Vegan Activists (ARVAs) in order to determine why and how ARVAs fail to convince people to become and stay veg*n, and what they might do to succeed. While ARVAs and ARVAism are the focus of this inquiry, the approaches, concepts and theories used are broadly applicable and therefore this investigation is potentially useful for any activist or group of activists wishing to interrogate and improve their persuasive practices. Keywords: Persuasion; Communication for Social Change; Animal Rights; Veg*nism; Activism iv Table of Contents Approval ............................................................................................................................. ii! Partial Copyright Licence ................................................................................................. -

Tracing Posthuman Cannibalism: Animality and the Animal/Human Boundary in the Texas Chain Saw Massacre Movies

The Cine-Files, Issue 14 (spring 2019) Tracing Posthuman Cannibalism: Animality and the Animal/Human Boundary in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre Movies Ece Üçoluk Krane In this article I will consider insights emerging from the field of Animal Studies in relation to a selection of films in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (hereafter TCSM) franchise. By paying close attention to the construction of the animal subject and the human-animal relation in the TCSM franchise, I will argue that the original 1974 film, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre II (1986) and the 2003 reboot The Texas Chain Saw Massacre all transgress the human-animal boundary in order to critique “carnism.”1 As such, these films exemplify “posthuman cannibalism,” which I define as a trope that transgresses the human-nonhuman boundary to undermine speciesism and anthropocentrism. In contrast, the most recent installment in the TCSM franchise Leatherface (2017) paradoxically disrupts the human-animal boundary only to re-establish it, thereby diverging from the earlier films’ critiques of carnism. For Communication scholar and animal advocate Carrie Packwood Freeman, the human/animal duality lying at the heart of speciesism is something humans have created in their own minds.2 That is, we humans typically do not consider ourselves animals, even though we may acknowledge evolution as a factual account of human development. Freeman proposes that we begin to transform this hegemonic mindset by creating language that would help humans rhetorically reconstruct themselves as animals. Specifically, she calls for the replacement of the term “human” with “humanimal” and the term “animal” with “nonhuman animal.”3 The advantage of Freeman’s terms is that instead of being mutually exclusive, they are mutually inclusive terms that foreground commonalities between humans and animals instead of differences. -

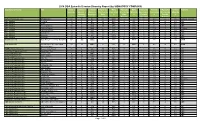

2014 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By SIGNATORY COMPANY)

2014 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SIGNATORY COMPANY) Signatory Company Title Total # of Combined # Combined # Episodes Male # Episodes Male # Episodes Female # Episodes Female Network Episodes Women + Women + Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Minority Minority % Male % Male % Female % Female % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority 50/50 Productions, LLC Workaholics 13 0 0% 13 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Comedy Central ABC Studios Betrayal 12 1 8% 11 92% 0 0% 1 8% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Castle 23 3 13% 20 87% 1 4% 2 9% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Criminal Minds 24 8 33% 16 67% 5 21% 2 8% 1 4% CBS ABC Studios Devious Maids 13 7 54% 6 46% 2 15% 4 31% 1 8% Lifetime ABC Studios Grey's Anatomy 24 7 29% 17 71% 1 4% 2 8% 4 17% ABC ABC Studios Intelligence 12 4 33% 8 67% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0% CBS ABC Studios Mixology 12 0 0% 13 108% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Revenge 22 6 27% 16 73% 0 0% 6 27% 0 0% ABC And Action LLC Tyler Perry's Love Thy Neighbor 52 52 100% 0 0% 52 100% 0 0% 0 0% OWN And Action LLC Tyler Perry's The Haves and 36 36 100% 0 0% 36 100% 0 0% 0 0% OWN The Have Nots BATB II Productions Inc. Beauty & the Beast 16 1 6% 15 94% 0 0% 1 6% 0 0% CW Black Box Productions, LLC Black Box, The 13 4 31% 9 69% 0 0% 4 31% 0 0% ABC Bling Productions Inc. -

Perceptions of Plant Based and Clean Meat 11/26/16 Who We Spoke To

Perceptions of Plant Based and Clean Meat 11/26/16 Who We Spoke To This poll was conducted online among 884 members of the American public between 11/1 and 11/4. There is a 3.3% margin of error. The sample has been weighted to be representative of the population as a whole. Executive Summary – Plant Alternatives 1. “Plant Based” is the most 2. Health is the major driver for effective branding meat alternatives The words “vegan” or “soy” The most persuasive reason for significantly depresses demand. consumers to look for plant-based Consumers are more likely to buy a alternatives to meat, is concern about “Plant Based” labeled food. meat being bad for their health. 3. Women are more positive 4. Young see plant alternatives as about meat alternatives a chance to experiment with Women are more likely than men to different foods see meat as unhealthy, and more Different messages work for different excited about trying plant-based age groups. Plant alternatives can be alternatives. pitched as fun to young people, and a healthy alternative to older ones. Executive Summary – Clean Meat 1. One in three consumers 2. Major concern is that clean would eat clean meat meat is “unnatural” This is a new concept for most The largest impediment for consumers consumers, and with only a brief is that clean meat is “unnatural.” This description, 30% of consumers say is followed by the accompanying issue they would eat clean meat. of food safety. 3. Women are far more 4. Animal welfare and health are skeptical then men best messages Even though women are more Health continues to be a high positive about meat alternatives – performing message. -

Bovine Benefactories: an Examination of the Role of Religion in Cow Sanctuaries Across the United States

BOVINE BENEFACTORIES: AN EXAMINATION OF THE ROLE OF RELIGION IN COW SANCTUARIES ACROSS THE UNITED STATES _______________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board _______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ________________________________________________________________ by Thomas Hellmuth Berendt August, 2018 Examing Committee Members: Sydney White, Advisory Chair, TU Department of Religion Terry Rey, TU Department of Religion Laura Levitt, TU Department of Religion Tom Waidzunas, External Member, TU Deparment of Sociology ABSTRACT This study examines the growing phenomenon to protect the bovine in the United States and will question to what extent religion plays a role in the formation of bovine sanctuaries. My research has unearthed that there are approximately 454 animal sanctuaries in the United States, of which 146 are dedicated to farm animals. However, of this 166 only 4 are dedicated to pigs, while 17 are specifically dedicated to the bovine. Furthermore, another 50, though not specifically dedicated to cows, do use the cow as the main symbol for their logo. Therefore the bovine is seemingly more represented and protected than any other farm animal in sanctuaries across the United States. The question is why the bovine, and how much has religion played a role in elevating this particular animal above all others. Furthermore, what constitutes a sanctuary? Does -

Reasonable Humans and Animals: an Argument for Vegetarianism

BETWEEN THE SPECIES Issue VIII August 2008 www.cla.calpoly.edu/bts/ Reasonable Humans and Animals: An Argument for Vegetarianism Nathan Nobis Philosophy Department Morehouse College, Atlanta, GA USA www.NathanNobis.com [email protected] “It is easy for us to criticize the prejudices of our grandfathers, from which our fathers freed themselves. It is more difficult to distance ourselves from our own views, so that we can dispassionately search for prejudices among the beliefs and values we hold.” - Peter Singer “It's a matter of taking the side of the weak against the strong, something the best people have always done.” - Harriet Beecher Stowe In my experience of teaching philosophy, ethics and logic courses, I have found that no topic brings out the rational and emotional best and worst in people than ethical questions about the treatment of animals. This is not surprising since, unlike questions about social policy, generally about what other people should do, moral questions about animals are personal. As philosopher Peter Singer has observed, “For most human beings, especially in modern urban and suburban communities, the most direct form of contact with non-human animals is at mealtimes: we eat Between the Species, VIII, August 2008, cla.calpoly.edu/bts/ 1 them.”1 For most of us, then, our own daily behaviors and choices are challenged when we reflect on the reasons given to think that change is needed in our treatment of, and attitudes toward, animals. That the issue is personal presents unique challenges, and great opportunities, for intellectual and moral progress. Here I present some of the reasons given for and against taking animals seriously and reflect on the role of reason in our lives. -

The Moral Standing of Animals: Towards a Psychology of Speciesism

The Moral Standing of Animals: Towards a Psychology of Speciesism Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Lucius Caviola, Jim A.C. Everett, and Nadira S. Faber University of Oxford We introduce and investigate the philosophical concept of ‘speciesism’ — the assignment of different moral worth based on species membership — as a psychological construct. In five studies, using both general population samples online and student samples, we show that speciesism is a measurable, stable construct with high interpersonal differences, that goes along with a cluster of other forms of prejudice, and is able to predict real-world decision- making and behavior. In Study 1 we present the development and empirical validation of a theoretically driven Speciesism Scale, which captures individual differences in speciesist attitudes. In Study 2, we show high test-retest reliability of the scale over a period of four weeks, suggesting that speciesism is stable over time. In Study 3, we present positive correlations between speciesism and prejudicial attitudes such as racism, sexism, homophobia, along with ideological constructs associated with prejudice such as social dominance orientation, system justification, and right-wing authoritarianism. These results suggest that similar mechanisms might underlie both speciesism and other well-researched forms of prejudice. Finally, in Studies 4 and 5, we demonstrate that speciesism is able to predict prosociality towards animals (both in the context of charitable donations and time investment) and behavioral food choices above and beyond existing related constructs. Importantly, our studies show that people morally value individuals of certain species less than others even when beliefs about intelligence and sentience are accounted for. -

HOW MUCH MEAT to EXPECT from a BEEF CARCASS Rob Holland, Director Center for Profitable Agriculture

PB 1822 HOW MUCH MEAT TO EXPECT FROM A BEEF CARCASS Rob Holland, Director Center for Profitable Agriculture Dwight Loveday, Associate Professor Department of Food Science and Technology Kevin Ferguson UT Extension Area Specialist-Farm Management University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture CONTENTS 2...Introduction 3...Dressing Percentage 5...Chilled Carcass and Primal Cuts 6...Sub-primal Meat Cuts 6...Factors Affecting Yield of Retail Cuts 7...Average Amount of Meat from Each Sub-primal Cut 9...Summary University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture Introduction Consumers who buy a live animal from a local cattle producer for custom processing are often surprised. Some are surprised at the quantity of meat and amount of freezer space they need. Others may be surprised that they did not get the entire live weight of the animal in meat cuts. The amount of meat actually available from a beef animal is a frequent source of misunderstanding between consumers, processors and cattle producers. This document provides information to assist in the understanding of how much meat to expect from a beef carcass. The information provided here should be helpful to consumers who purchase a live animal for freezer beef and to cattle producers involved in direct and retail meat marketing. 2 University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture How Much Meat to Expect from a Beef Carcass Dressing Percentage One of the terms used in the cattle and meat cutting industry that often leads to misunderstanding is dressing percentage. The dressing percentage is the portion of the live animal weight that results in the hot carcass.