Henry VIII and the Reformation Teachers Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walk 9 - a Walk to the Past

Woodhall Spa Walks No 9 Walk 9 - A walk to the past Start from Royal Square - Grid Reference: TF 193631 Approx 1 hour This route takes the walker to the ruins of Kirkstead Abbey, (dissolved by Henry VIII over 300 years before Woodhall Spa came into being) and the little 13th Century Church of St Leonards. From Royal Square, take the Witham Road, towards the river, passing shops and houses until fields open out to your left. Soon after, look for the entrance to Abbey Lane (to the left). Follow this narrow lane. You will eventually cross the Beck (see also walks 6 and 7) as it approaches the river; the monks from the Abbey once re-routed it to obtain drinking water. Ahead, on the right, is Kirkstead Old Hall, which dates from the 17th Century. Following the land, you cannot miss the Abbey ruin ahead. All that remains now is part of the Abbey Church, but under the humps and bumps of the field are other remains that have yet to be properly excavated, though a brief exploration before the laqst war revealed some of the magnificence of the Cistercian Abbey. Beyond is the superb little Church of St Leonards ( the patron saint of prisoners), believed to have been built as a Chantry Chapel and used by travellers and local inhabitants. The Cistercians were great agriculturalists and wool from the Abbey lands commanded a high price for its quality. A whole community of craftsmen and labourers would have grown up around the Abbey as iut gained lands and power. -

York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399

York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399 Edited by David M. Smith 2020 www.york.ac.uk/borthwick archbishopsregisters.york.ac.uk Online images of the Archbishops’ Registers cited in this edition can be found on the York’s Archbishops’ Registers Revealed website. The conservation, imaging and technical development work behind the digitisation project was delivered thanks to funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Register of Alexander Neville 1374-1388 Register of Thomas Arundel 1388-1396 Sede Vacante Register 1397 Register of Robert Waldby 1397 Sede Vacante Register 1398 Register of Richard Scrope 1398-1405 YORK CLERGY ORDINATIONS 1374-1399 Edited by DAVID M. SMITH 2020 CONTENTS Introduction v Ordinations held 1374-1399 vii Editorial notes xiv Abbreviations xvi York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399 1 Index of Ordinands 169 Index of Religious 249 Index of Titles 259 Index of Places 275 INTRODUCTION This fifth volume of medieval clerical ordinations at York covers the years 1374 to 1399, spanning the archiepiscopates of Alexander Neville, Thomas Arundel, Robert Waldby and the earlier years of Richard Scrope, and also including sede vacante ordinations lists for 1397 and 1398, each of which latter survive in duplicate copies. There have, not unexpectedly, been considerable archival losses too, as some later vacancy inventories at York make clear: the Durham sede vacante register of Alexander Neville (1381) and accompanying visitation records; the York sede vacante register after Neville’s own translation in 1388; the register of Thomas Arundel (only the register of his vicars-general survives today), and the register of Robert Waldby (likewise only his vicar-general’s register is now extant) have all long disappeared.1 Some of these would also have included records of ordinations, now missing from the chronological sequence. -

9780521650601 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 0521650607 - Pragmatic Utopias: Ideals and Communities, 1200-1630 Edited by Rosemary Horrox and Sarah Rees Jones Index More information Index Aberdeen, Baxter,Richard, Abingdon,Edmund of,archbp of Canterbury, Bayly,Thomas, , Beauchamp,Richard,earl of Warwick, – Acthorp,Margaret of, Beaufort,Henry,bp of Winchester, adultery, –, Beaufort,Margaret,countess of Richmond, Aelred, , , , , , Aix en Provence, Beauvale Priory, Alexander III,pope, , Beckwith,William, Alexander IV,pope, Bedford,duke of, see John,duke of Bedford Alexander V,pope, beggars, –, , Allen,Robert, , Bell,John,bp of Worcester, All Souls College,Oxford, Belsham,John, , almshouses, , , , –, , –, Benedictines, , , , , –, , , , , , –, , – Americas, , Bereford,William, , anchoresses, , – Bergersh,Maud, Ancrene Riwle, Bernard,Richard, –, Ancrene Wisse, –, Bernwood Forest, Anglesey Priory, Besan¸con, Antwerp, , Beverley,Yorks, , , , apostasy, , , – Bicardike,John, appropriations, –, , , , Bildeston,Suff, , –, , Arthington,Henry, Bingham,William, – Asceles,Simon de, Black Death, , attorneys, – Blackwoode,Robert, – Augustinians, , , , , , Bohemia, Aumale,William of,earl of Yorkshire, Bonde,Thomas, , , –, Austria, , , , Boniface VIII,pope, Avignon, Botreaux,Margaret, –, , Aylmer,John,bp of London, Bradwardine,Thomas, Aymon,P`eire, , , , –, Brandesby,John, Bray,Reynold, Bainbridge,Christopher,archbp of York, Brinton,Thomas,bp of Rochester, Bristol, Balliol College,Oxford, , , , , , Brokley,John, Broomhall -

The Northern Clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace Keith Altazin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The northern clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace Keith Altazin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Altazin, Keith, "The northern clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 543. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/543 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE NORTHERN CLERGY AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Keith Altazin B.S., Louisiana State University, 1978 M.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2003 August 2011 Acknowledgments The completion of this dissertation would have not been possible without the support, assistance, and encouragement of a number of people. First, I would like to thank the members of my doctoral committee who offered me great encouragement and support throughout the six years I spent in the graduate program. I would especially like thank Dr. Victor Stater for his support throughout my journey in the PhD program at LSU. From the moment I approached him with my ideas on the Pilgrimage of Grace, he has offered extremely helpful advice and constructive criticism. -

River Witham the Source of the 8Th Longest River Wholly in England Is

River Witham The source of the 8th longest river wholly in England is just outside the county, Lincolnshire, through which it follows almost all of a 132km course to the sea, which is shown on the map which accompanies Table Wi1 at the end of the document. Three kilometres west of the village of South Witham, on a minor road called Fosse Lane, a sign points west over a stile to a nature reserve. There, the borders of 3 counties, Lincolnshire, Rutland and Leicestershire meet. The reserve is called Cribb’s Meadow, named for a famous prize fighter of the early 19th century; at first sight a bizarre choice at such a location, though there is a rational explanation. It was known as Thistleton Gap when Tom Cribb had a victory here in a world championship boxing match against an American, Tom Molineaux, on 28th September 1811; presumably it was the only time he was near the place, as he was a Bristolian who lived much of his life in London. The organisers of bare-knuckle fights favoured venues at such meeting points of counties, which were distant from centres of population; they aimed to confuse Justices of the Peace who had a duty to interrupt the illegal contests. Even if the responsible Justices managed to attend and intervene, a contest might be restarted nearby, by slipping over the border into a different jurisdiction. In this fight, which bore little resemblance to the largely sanitised boxing matches of today, it is certain that heavy blows were landed, blood was drawn, and money changed hands, before Cribb won in 11 rounds; a relatively short fight, as it had taken him over 30 rounds to beat the same opponent at the end of the previous year to win his title. -

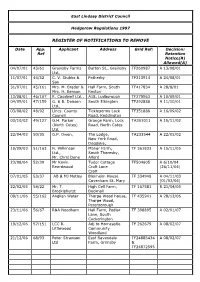

Register of Notifications to Remove

East Lindsey District Council Hedgerow Regulations 1997 REGISTER OF NOTIFICATIONS TO REMOVE Date App. Applicant Address Grid Ref: Decision: Ref Retention Notice(R) Allowed(A) 04/07/01 43/61 Grainsby Farms Barton St., Grainsby TF260987 A 13/08/01 Ltd., 11/07/01 44/52 C. V. Stubbs & Fotherby TF313914 A 24/08/01 Son 31/07/01 45/161 Mrs. M. Brader & Hall Farm, South TF417834 A 28/8/01 Mrs. H. Benson Reston 13/08/01 46/107 R. Caudwell Ltd., A18, Ludborough TF279963 A 10/09/01 04/09/01 47/159 G. & B. Dobson South Elkington TF292888 A 11/10/01 Ltd., 03/08/02 48/92 Lincs. County Ticklepenny Lock TF351888 A 16/09/02 Council Road, Keddington 03/10/02 49/127 G.H. Parker Grange Farm, Lock TA351011 A 15/11/02 (North Cotes) Road, North Cotes Ltd. 22/04/03 50/35 G.P. Owen, The Lodge, TA233544 A 22/05/02 New York Road, Dogdyke, 10/09/03 51/163 N. Wilkinson Manor Farm, TF 361833 A 15/11/05 Ltd., South Thoresby, Mr. Chris Done Alford 23/08/04 52/39 Mr Kevin Tudor Cottage TF504605 A 6/10/04 Beardwood Croft Lane (26/11/04) Croft 07/01/05 53/37 AB & MJ Motley Blenheim House TF 334948 A 04/11/03 Covenham St. Mary (01/03/04) 22/02/05 54/22 Mr. T. High Cell Farm, TF 167581 R 21/04/05 Brocklehurst Bucknall 09/11/06 55/162 Anglian Water Thorpe Wood house, TF 435941 A 28/12/06 Thorpe Wood, Peterborough 23/11/06 56/67 R&A Needham Hall Farm, Pedlar TF 398895 A 02/01/07 Lane, South Cockerington 19/12/06 57/151 LCC R. -

The Landscape Speaks – Dowsing Discoveries

A PDF OF THIS DOCUMENT CAN BE DOWNLOADED FROM http://www.dangreencodex.co.uk/contributor.html THE LANDSCAPE SPEAKS – DOWSING DISCOVERIES Introduction This is a summary of the various landscape geometries I have discovered (or more correctly, that have discovered me) since 2006. They include several landscape pentagrams, a 200 mile alignment with a pairing of earth energy dragon currents, a terrestrial representation of the celestial winter and summer triangles and a mirror-image of the constellation Cygnus surrounded by a landscape image of the head of Baphomet and enclosed by yet another a pentagram. Many of these landscape features link into one another when various lines are extended. They also link into geometries and alignments discovered by other researchers. Moreover, much of the geometry seems to link in with Lincoln and Dan Green’s Lincoln Cathedral Code. The document is also a summary of my current ideas and suggestions about the nature of earth energies, particularly earth energy vortexes and the earth energy “dragon” currents that weave through the landscape. I believe that together these two energetic features form part of the earth’s own self-cleansing and healing system, which is currently not working to anywhere near its full potential. Merlina Rose Sherwood Forest September 2015 [email protected] 2 THE LANDSCAPE SPEAKS – DOWSING DISCOVERIES Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 2 1. The Middle -

The Transport System of Medieval England and Wales

THE TRANSPORT SYSTEM OF MEDIEVAL ENGLAND AND WALES - A GEOGRAPHICAL SYNTHESIS by James Frederick Edwards M.Sc., Dip.Eng.,C.Eng.,M.I.Mech.E., LRCATS A Thesis presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Salford Department of Geography 1987 1. CONTENTS Page, List of Tables iv List of Figures A Note on References Acknowledgements ix Abstract xi PART ONE INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter One: Setting Out 2 Chapter Two: Previous Research 11 PART TWO THE MEDIEVAL ROAD NETWORK 28 Introduction 29 Chapter Three: Cartographic Evidence 31 Chapter Four: The Evidence of Royal Itineraries 47 Chapter Five: Premonstratensian Itineraries from 62 Titchfield Abbey Chapter Six: The Significance of the Titchfield 74 Abbey Itineraries Chapter Seven: Some Further Evidence 89 Chapter Eight: The Basic Medieval Road Network 99 Conclusions 11? Page PART THREE THr NAVIGABLE MEDIEVAL WATERWAYS 115 Introduction 116 Chapter Hine: The Rivers of Horth-Fastern England 122 Chapter Ten: The Rivers of Yorkshire 142 Chapter Eleven: The Trent and the other Rivers of 180 Central Eastern England Chapter Twelve: The Rivers of the Fens 212 Chapter Thirteen: The Rivers of the Coast of East Anglia 238 Chapter Fourteen: The River Thames and Its Tributaries 265 Chapter Fifteen: The Rivers of the South Coast of England 298 Chapter Sixteen: The Rivers of South-Western England 315 Chapter Seventeen: The River Severn and Its Tributaries 330 Chapter Eighteen: The Rivers of Wales 348 Chapter Nineteen: The Rivers of North-Western England 362 Chapter Twenty: The Navigable Rivers of -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'. -

Late Antiquity & Byzantium

Late Antiquity & Byzantium Constantine Forthcoming from Oxbow Books Religious Faith and Imperial Policy Edited by A. Edward Siecienski The Bir Messaouda Basilica Pilgrimage and the Transformation of an Urban Contents: Constantine and religious extremism Landscape in Sixth Century AD Carthage (H.A. Drake); The significance of the Edict of Milan (Noel Lenski); The sources for our sources: By Richard Miles & Simon Greenslade Eusebius and Lactantius on Constantine in 312-313 This volume charts the (Raymond Van Dam); Constantine in the pagan radical transformation of an memory (Mark Edwards); Writing Constantine inner city neighbourhood in (David Potter) The Eusebian valorization of late antique Carthage which violence and Constantine’s wars for God (George was excavated over a five-year E. Demacopoulos); Constantine the Pious (Peter J. period by a team from the Leithart). University of Cambridge. The 160p b/w illus (Routledge 2017) 9781472454133 Hb neighbourhood remained £110.00 primarily a residential one from the second century until The Architecture of the Christian 530s AD when a substantial Holy Land basilica was constructed over Reception from Late Antiquity through the eastern half of the insula. Further extensive the Renaissance modifications were made to the basilica half-a- century later when the structures on the western half By Kathryn Blair Moore of the insula were demolished and the basilica greatly Architecture took on a special representational role enlarged with the addition of a new east-west aisles, during the Christian Middle Ages, marking out sites a large monumental baptistery and a crypt. The Bir associated with the bodily presence of the dominant Messaouda basilica provides important insights into figures of the religion. -

Bolingbroke Castle Report

Geophysical Survey Report BOLINGBROKE CASTLE AND DEWY HILL LINCOLNSHIRE Prepared for by Archaeological Project Services / Heritage Lincolnshire Date: August 2018 The Old School Cameron Street Heckington Sleaford Lincolnshire NG34 9RW Document Control Project Name Bolingbroke Castle Author(s) and contact details Sean Parker Tel: 01529 461499 Email: [email protected] Origination Date August 2018 Reviser(s) Paul Cope -Faulkner Date of Last Revision 29 /08/2018 Version 1.0 Summar y of Changes Site name Bolingbroke Castle and Dewy Hill -Geophysical Survey Report Listing No. 1008318 Listing name Bolingbroke Castle National Grid Reference TF 3493 6501 Report reference 57/18 BOLINGBROKE CASTLE AND DEWY HILL, LINCOLNSHIRE: GEOPHYSICAL SURVEY REPORT CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 1 2. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 2.1 DEFINITION OF AN EVALUATION .................................................................................................... 1 2.2 PROJECT BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................... 1 2.3 TOPOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY ........................................................................................................ 1 2.4 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SETTING ......................................................................................................... -

THE UNIVERSITY of HULL John De Da1derby

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL John de Da1derby, Bishop 1300 of Lincoln, - 1320 being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Clifford Clubley, M. A. (Leeds) March, 1965 r' ý_ý ki "i tI / t , k, CONTENTS Page 1 Preface """ """ """ """ """ Early Life ... ... ... ... ... 2 11 The Bishop's Household ... ... ... ... Diocesan Administration ... ... ... ... 34 Churches 85 The Care of all the . ... ... ... Religious 119 Relations with the Orders. .. " ... Appendices, Dalderby's 188 A. Itinerary ... ... B. A Fragment of Dalderby's Ordination Register .. 210 C. Table of Appointments ... ... 224 ,ý. ý, " , ,' Abbreviations and Notes A. A. S. R. Reports of the Lincolnshire Associated architectural Archaeological Societies. and Cal. Calendar. C. C. R. Calendar of Close Rolls C. P. R. Calendar of Patent Rolls D&C. Dean and Chapter's Muniments E. H. R. English History Review J. E. H. Journal of Ecclesiastical History L. R. S. Lincoln Record Society O. H. S. Oxford Historical Society Reg. Register. Reg. Inst. Dalderby Dalderby's Register of Institutions, also known as Bishopts Register No. II. Reg. Mem. Dalderby Dalderby's Register of Memoranda, or Bishop's Register No. III. The folios of the Memoranda Register were originally numbered in Roman numerals but other manuscripts were inserted Notes, continued when the register was bound and the whole volume renumbered in pencil. This latter numeration is used in the references given in this study. The Vetus Repertorium to which reference is made in the text is a small book of Memoranda concerning the diocese of Lincoln in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. The original is in the Cambridge University Library, No.