High-Throughput Platform for Efficient Chemical Transfection, Virus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile Genetic Elements in Streptococci

Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. (2019) 32: 123-166. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21775/cimb.032.123 Mobile Genetic Elements in Streptococci Miao Lu#, Tao Gong#, Anqi Zhang, Boyu Tang, Jiamin Chen, Zhong Zhang, Yuqing Li*, Xuedong Zhou* State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, PR China. #Miao Lu and Tao Gong contributed equally to this work. *Address correspondence to: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Streptococci are a group of Gram-positive bacteria belonging to the family Streptococcaceae, which are responsible of multiple diseases. Some of these species can cause invasive infection that may result in life-threatening illness. Moreover, antibiotic-resistant bacteria are considerably increasing, thus imposing a global consideration. One of the main causes of this resistance is the horizontal gene transfer (HGT), associated to gene transfer agents including transposons, integrons, plasmids and bacteriophages. These agents, which are called mobile genetic elements (MGEs), encode proteins able to mediate DNA movements. This review briefly describes MGEs in streptococci, focusing on their structure and properties related to HGT and antibiotic resistance. caister.com/cimb 123 Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. (2019) Vol. 32 Mobile Genetic Elements Lu et al Introduction Streptococci are a group of Gram-positive bacteria widely distributed across human and animals. Unlike the Staphylococcus species, streptococci are catalase negative and are subclassified into the three subspecies alpha, beta and gamma according to the partial, complete or absent hemolysis induced, respectively. The beta hemolytic streptococci species are further classified by the cell wall carbohydrate composition (Lancefield, 1933) and according to human diseases in Lancefield groups A, B, C and G. -

Dharmacon™ Edit-R™ CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Products

GE Healthcare Specific, functional and scalable Dharmacon™ Edit-R™ CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Products CR SPR Table of Contents Page 4 Dharmacon™ Gene Editing Workflows Page 8 Edit-R CRISPR Guide RNA Page 22 Edit-R Cas9 Nuclease Page 30 Edit-R CRISPR-Cas9 Screening Libraries Page 37 Guide RNA Design with the Dharmacon™ CRISPR RNA Configurator Page 40 Delivery solutions for Gene Editing Application Notes Page 44 A CRISPR-Cas9 gene engineering workflow: generating functional knockouts using Edit-R™ Cas9 and synthetic crRNA and tracrRNA Page 50 Homology-directed repair with Dharmacon™ Edit-R™ CRISPR-Cas9 reagents and single-stranded DNA oligos Page 54 Microinjection of zebrafish embryos using Dharmacon™ Edit-R™ Cas9 Nuclease mRNA, synthetic crRNA, and tracrRNA for genome engineering Page 58 Optimization of reverse transfection of Dharmacon™ Edit-R™ synthetic crRNA and tracrRNA components with DharmaFECT™ transfection reagent in a Cas9-expressing cell line 3 Dharmacon™ Gene Editing Workflows Choose your application Choose the right tools for your application Whether you’re goal is gene Gene knockout Gene knockin knockout from imperfect precise insertion or alteration of a gene repair by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or creating an insertion or other knockin with Loss-of-function homology-directed repair (HDR), Single gene knockout screening of multiple this workflow guide will assist genes at once you in selecting the right Edit-R™ genome engineering tools for Knockout cell line creation your application. or loss-of-function analysis in -

Horizontal Gene Transfer

Genetic Variation: The genetic substrate for natural selection Horizontal Gene Transfer Dr. Carol E. Lee, University of Wisconsin Copyright ©2020; Do not upload without permission What about organisms that do not have sexual reproduction? In prokaryotes: Horizontal gene transfer (HGT): Also termed Lateral Gene Transfer - the lateral transmission of genes between individual cells, either directly or indirectly. Could include transformation, transduction, and conjugation. This transfer of genes between organisms occurs in a manner distinct from the vertical transmission of genes from parent to offspring via sexual reproduction. These mechanisms not only generate new gene assortments, they also help move genes throughout populations and from species to species. HGT has been shown to be an important factor in the evolution of many organisms. From some basic background on prokaryotic genome architecture Smaller Population Size • Differences in genome architecture (noncoding, nonfunctional) (regulatory sequence) (transcribed sequence) General Principles • Most conserved feature of Prokaryotes is the operon • Gene Order: Prokaryotic gene order is not conserved (aside from order within the operon), whereas in Eukaryotes gene order tends to be conserved across taxa • Intron-exon genomic organization: The distinctive feature of eukaryotic genomes that sharply separates them from prokaryotic genomes is the presence of spliceosomal introns that interrupt protein-coding genes Small vs. Large Genomes 1. Compact, relatively small genomes of viruses, archaea, bacteria (typically, <10Mb), and many unicellular eukaryotes (typically, <20 Mb). In these genomes, protein-coding and RNA-coding sequences occupy most of the genomic sequence. 2. Expansive, large genomes of multicellular and some unicellular eukaryotes (typically, >100 Mb). In these genomes, the majority of the nucleotide sequence is non-coding. -

Transduction by Bacteriophage Ti * Henry Drexler

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Vol. 66, No. 4, pp. 1083-1088, August 1970 Transduction by Bacteriophage Ti * Henry Drexler DEPARTMENT OF MICROBIOLOGY, BOWMAN GRAY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE, WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY, WINSTON-SALEM, NORTH CAROLINA Communicated by Edward L. Tatum, May 25, 1970 Abstract. Amber mutants of the virulent coliphage T1 are able to transduce a wide variety of genetic characteristics from permissive to nonpermissive K strains of Escherichia coli. The virulent coliphage T1 is not known to be related to any temperate phage. Certain of the characteristics of T1 seem to be incompatible with its potential existence as a temperate phage; for example, the average latent period for T1 is only 13 min' and about 70% of its DNA is derived from the host.2 In order to demonstrate transduction by T1 it is necessray to provide condi- tions in which potential transductants are able to survive; this is accomplished by using amber mutants of T1 to transduce nonpermissive recipients. Experi- ments which show that T1 is a transducing phage are presented and have been designed chiefly to illustrate the following points: (1) Infection by T1 is able to cause heritable changes in recipients; (2) the genotype of the donor host is im- portant in determining what characteristics can be transferred to recipients; (3) the changes in the recipients are not caused by transformation; and (4) there is a similarity between the transducing activity and the plaque-forming ability of T1 with respect to serology, host range, and density. Materials and Methods. Bacterial strains: The abbreviations and symbols of Demerec et al.3 and Taylor and Trotter4 are used to describe all pertinent genotypes. -

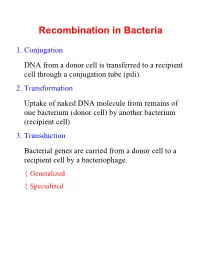

Recombination in Bacteria

Recombination in Bacteria 1. Conjugation DNA from a donor cell is transferred to a recipient cell through a conjugation tube (pili). 2. Transformation Uptake of naked DNA molecule from remains of one bacterium (donor cell) by another bacterium (recipient cell). 3. Transduction Bacterial genes are carried from a donor cell to a recipient cell by a bacteriophage. { Generalized { Specialized Conjugation Ability to conjugate located on the F-plasmid F+ Cells act as donors F- Cells act as recipients F+/F- Conjugation: { F Factor “replicates off” a single strand of DNA. { New strand goes through pili to recipient cell. { New strand is made double stranded. { If entire F-plasmid crosses, then recipient cell becomes F+, otherwise nothing happens Conjugation with Hfr Hfr cell (High Frequency Recombination) cells have F-plasmid integrated into the Chromosome. Integration into the Chromosome is unique for each F-plasmid strain. When F-plasmid material is replicated and sent across pili, Chromosomal material is included. (Figure 6.10 in Klug & Cummings) When chromosomal material is in recipient cell, recombination can occur: { Recombination is double stranded. { Donor genes are recombined into the recipient cell. { Corresponding genes from recipient cell are recombined out of the chromosome and reabsorbed by the cell. Interrupted Mating Mapping 1. Allow conjugation to start Genes closest to the origin of replication site (in the direction of replication) are moved through the pili first. 2. After a set time, interrupt conjugation Only those genes closest to the origin of replication site will conjugate. The long the time, the more that is able to conjugate. 3. -

Microbial Genetics by Dr Preeti Bajpai

Dr. Preeti Bajpai Genes: an overview ▪ A gene is the functional unit of heredity ▪ Each chromosome carry a linear array of multiple genes ▪ Each gene represents segment of DNA responsible for synthesis of RNA or protein product ▪ A gene is considered to be unit of genetic information that controls specific aspect of phenotype DNA Chromosome Gene Protein-1 Prokaryotic Courtesy: Team Shrub https://twitter.com/realscientists/status/927 cell 667237145767937 Genetic exchange within Prokaryotes The genetic exchange occurring in bacteria involve transfers of genes from one bacterium to another. The gene transfer in prokaryotic cells is thus unidirectional and the recombination events usually occur between a fragment of one chromosome (from a donor cell) and a complete chromosome (in a recipient cell) Mechanisms for genetic exchange Bacteria exchange genetic material through three different parasexual processes* namely transformation, conjugation and transduction. *Parasexual process involves recombination of genes from genetically distinct cells occurring without involvement of meiosis and fertilization Principles of Genetics-sixth edition Courtesy: Beatrice the Biologist.com by D. Peter Snustad & Michael J. Simmons (http://www.beatricebiologist.com/2014/08/bacterial-gifts/) Transformation: an introduction Transformation involves the uptake of free DNA molecules released from one bacterium (the donor cell) by another bacterium (the recipient cell). Frederick Griffith discovered transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) in 1928. In his experiments, Griffith used two related strains of bacteria, known as R and S. The R bacteria (nonvirulent) formed colonies, or clumps of related bacteria, that Frederick Griffith 1877-1941 had a rough appearance (hence the abbreviation "R"). The S bacteria (virulent) formed colonies that were rounded and smooth (hence the abbreviation "S"). -

Virapower™ Lentiviral Expression Systems Lentiviral Systems for High-Level Expression in Dividing and Non-Dividing Mammalian Cells

ViraPower™ Lentiviral Expression Systems Lentiviral systems for high-level expression in dividing and non-dividing mammalian cells Catalog nos. K4950-00, K4960-00, K4970-00, K4975-00, K4980-00, K4985-00, K4990-00, K367-20, K370-20, and K371-20 Version G 14 April, 2006 25-0501 Corporate Headquarters Invitrogen Corporation 1600 Faraday Avenue Carlsbad, CA 92008 T: 1 760 603 7200 F: 1 760 602 6500 User Manual E: [email protected] For country-specific contact information visit our web site at www.invitrogen.com ii Table of Contents Kit Contents and Storage........................................................................................................................................... v Accessory Products ................................................................................................................................................... ix Product Qualification................................................................................................................................................. x Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 Overview...................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Biosafety Features of the System .............................................................................................................................. 4 Experimental Outline................................................................................................................................................ -

Comprehensive Analysis of Mobile Genetic Elements in the Gut Microbiome Reveals Phylum-Level Niche-Adaptive Gene Pools

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/214213; this version posted December 22, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Comprehensive analysis of mobile genetic elements in the gut microbiome 2 reveals phylum-level niche-adaptive gene pools 3 Xiaofang Jiang1,2,†, Andrew Brantley Hall2,3,†, Ramnik J. Xavier1,2,3,4, and Eric Alm1,2,5,* 4 1 Center for Microbiome Informatics and Therapeutics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 5 Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 6 2 Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA 7 3 Center for Computational and Integrative Biology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard 8 Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA 9 4 Gastrointestinal Unit and Center for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Massachusetts General 10 Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA 11 5 MIT Department of Biological Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 12 02142, USA 13 † Co-first Authors 14 * Corresponding Author bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/214213; this version posted December 22, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 15 Abstract 16 Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) drive extensive horizontal transfer in the gut microbiome. This transfer 17 could benefit human health by conferring new metabolic capabilities to commensal microbes, or it could 18 threaten human health by spreading antibiotic resistance genes to pathogens. Despite their biological 19 importance and medical relevance, MGEs from the gut microbiome have not been systematically 20 characterized. -

Molecular Model for the Transposition and Replication of Bacteriophage

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 76, No. 4, pp. 1933-1937, April 1979 Genetics Molecular model for the transposition and replication of bacteriophage Mu and other transposable elements (DNA insertion elements/nonhomologous recombination/site-specific recombination/replicon fusion/topoisomerases) JAMES A. SHAPIRO Department of Microbiology, The University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637 Communicated by Hewson Swift, December 11, 1978 ABSTRACT A series of molecular events will explain how B genetic elements can transpose from one DNA site to another, B y generate a short oligonucleotide duplication at both ends of the I % new insertion site, and replicate in the transposition process. I These events include the formation of recombinant molecules A a% /; C which have been postulated to be intermediates in the trans- position process. The model explains how the replication of bacteriophage Mu is obligatorily associated with movement to z x x new genetic sites. It postulates that all transposable elements replicate in the transposition process so that they remain at their z original site while moving to new sites. According to this model, the mechanism of transposition is very different from the in- V sertion and excision of bacteriophage X. y FIG. 1. Replicon fusion. The boxes with an arrow indicate copies Recent research on transposable elements in bacteria has pro- of a transposable element. The letters mark arbitrary regions of the vided important insights into the role of nonhomologous re- two replicons to indicate the relative positions of the elements in the combination in genetic rearrangements (1-4). These elements donor and cointegrate molecules. include small insertion sequences (IS elements), transposable resistance determinants (Tn elements), and bacteriophage Mu results in the duplication of a short oligonucleotide sequence (3). -

Enhanced Transfection Efficiency of Human Embryonic Stem Cells By

STEM CELLS AND DEVELOPMENT Volume 19, Number 12, 2010 ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089=scd.2009.0505 Enhanced Transfection Efficiency of Human Embryonic Stem Cells by the Incorporation of DNA Liposomes in Extracellular Matrix Luis G. Villa-Diaz,1,* Jose L. Garcia-Perez,2,* and Paul H. Krebsbach1,3 Because human embryonic stem (hES) cells can differentiate into virtually any cell type in the human body, these cells hold promise for regenerative medicine. The genetic manipulation of hES cells will enhance our under- standing of genes involved in early development and will accelerate their potential use and application for regenerative medicine. The objective of this study was to increase the transfection efficiency of plasmid DNA into hES cells by modifying a standard reverse transfection (RT) protocol of lipofection. We hypothesized that immobilization of plasmid DNA in extracellular matrix would be a more efficient method for plasmid transfer due to the affinity of hES cells for substrates such as Matrigel and to the prolonged exposure of cells to plasmid DNA. Our results demonstrate that this modification doubled the transfection efficiency of hES cells and the generation of clonal cell lines containing a piece of foreign DNA stably inserted in their genomes compared to results obtained with standard forward transfection. In addition, treatment with dimethyl sulfoxide further increased the transfection efficiency of hES cells. In conclusion, modifications to the RT protocol of lipofection result in a significant and robust increase in the transfection efficiency of hES cells. Introduction [6,8,11–13], nucleofection [14,15], and the use of nanoparticles [16]. -

Functional Analysis of Meloidogyne Graminicola C-Type Lectins and Their Role in the Nematode – Rice Interaction

University of Ghent Faculty of Science Department of Biology Academic year 2013 – 2015 Functional Analysis of Meloidogyne graminicola C-type Lectins and their Role in the Nematode – Rice Interaction Romnick Latina Promotor: Prof. Dr. Godelieve Gheysen Thesis submitted to obtain the degree Supervisor: Silke Nowak of Master of Science in Nematology Functional analysis of Meloidogyne graminicola C-type lectins and their role in the nematode – rice interaction Romnick LATINA Faculty of Science, Department of Biology, Ghent University, K.L. Ledeganckstraat 35, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium Summary – Due to rice cropping intensification and increasing water scarcity, Meloidogyne graminicola has become a threat to rice production. With the aid of molecular tools and techniques, the host-nematode interaction has long been studied in the hope of finding control measures for this ominous rice root-knot nematode. In many investigations, proteins termed as effectors have been shown to mediate mechanisms and processes essential for pathogenesis of plant parasitic nematodes. Many of these effectors have been identified to unravel their functional roles. In this present work, two putative effector genes (UK41 and UK42) coding C-type lectins were investigated to know their roles in the M. graminicola - rice interaction. To gain some insights on their action site, eGFP fusion constructs were transiently expressed in N. benthamiana. Subcellular localizations revealed that UK41 localized to both the cytoplasm and nucleus while UK42 showed strong nuclear localization. To check their effect on host defenses, ETI and PTI assays were performed using transient expression in tobacco plants. Based on the R/Avr-gene pairs tested, both C-type lectins were found to be non-suppressive of the ETI. -

Section 4. Guidance Document on Horizontal Gene Transfer Between Bacteria

306 - PART 2. DOCUMENTS ON MICRO-ORGANISMS Section 4. Guidance document on horizontal gene transfer between bacteria 1. Introduction Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) 1 refers to the stable transfer of genetic material from one organism to another without reproduction. The significance of horizontal gene transfer was first recognised when evidence was found for ‘infectious heredity’ of multiple antibiotic resistance to pathogens (Watanabe, 1963). The assumed importance of HGT has changed several times (Doolittle et al., 2003) but there is general agreement now that HGT is a major, if not the dominant, force in bacterial evolution. Massive gene exchanges in completely sequenced genomes were discovered by deviant composition, anomalous phylogenetic distribution, great similarity of genes from distantly related species, and incongruent phylogenetic trees (Ochman et al., 2000; Koonin et al., 2001; Jain et al., 2002; Doolittle et al., 2003; Kurland et al., 2003; Philippe and Douady, 2003). There is also much evidence now for HGT by mobile genetic elements (MGEs) being an ongoing process that plays a primary role in the ecological adaptation of prokaryotes. Well documented is the example of the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes by HGT that allowed bacterial populations to rapidly adapt to a strong selective pressure by agronomically and medically used antibiotics (Tschäpe, 1994; Witte, 1998; Mazel and Davies, 1999). MGEs shape bacterial genomes, promote intra-species variability and distribute genes between distantly related bacterial genera. Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) between bacteria is driven by three major processes: transformation (the uptake of free DNA), transduction (gene transfer mediated by bacteriophages) and conjugation (gene transfer by means of plasmids or conjugative and integrated elements).