Changes in Received Pronunciation: Diachronic Case Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Thomson CV

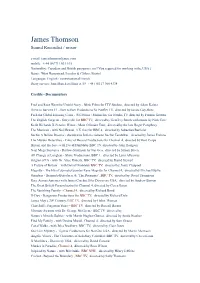

James Thomson Sound Recordist / mixer e-mail: [email protected] mobile: + 44 (0)7711 031 615 Nationality: Canadian and British passports ( no I Visa required for working in the USA ) Bases: West Hampstead, London & Clifton, Bristol Languages: English / conversational French Diary service: Jane Murch at Films at 59 + 44 ( 0)117 906 4334 Credits - Documentary Fred and Rose West the Untold Story - Blink Films for ITV Studios, directed by Adam Kaleta Drive to Survive F1 - Box to Box Productions for Netflix TV, directed by James Gay-Rees Push the Global Housing Crisis - WG Films / Malmo Inc for Netflix TV, directed by Fredrik Gertten The English Surgeon - Storyville for BBC TV, directed by Geoffrey Smith with music by Nick Cave Keith Richards X-Pensive Winos - Main Offender Tour, directed by the late Roger Pomphrey The Musicals - with Neil Brand, 3 X 1hrs for BBC 4, directed by Sebastian Barfield Sachin A Billion Dreams - docudrama Indian cricketer Sachin Tendulkar, directed by James Erskine The Murder Detectives - Films of Record Productions for Channel 4, directed by Bart Corpe Britain and the Sea - with David Dimbleby BBC TV, directed by John Hodgson Nazi Mega Stuctures - Darlow-Smithson for Nat Geo, directed by Simon Breen All Change at Longleat - Shine Productions, BBC 1, directed by Lynn Alleyway Origins of Us - with Dr. Alice Roberts, BBC TV, directed by David Stewart A Picture of Britain – with David Dimbleby BBC TV, directed by Jonty Claypool Magritte - The life of surrealist painter Rene Magritte for Channel 4, directed by Michael Burke Omnibus - Bernardo Bertolucci & ‘The Dreamers’, BBC TV, directed by David Thompson Race Across America with James Cracknell for Discovery USA, directed by Andrew Barron The Great British Paraorchestra for Channel 4, directed by Cesca Eaton The Vanishing Family - Channel 4, directed by Richard Bond D-Day - Dangerous Productions for BBC TV, directed by Richard Dale James May’s 20th Century, BBC TV, directed by Helen Thomas Churchill’s Forgotten Years – BBC TV, directed by Russell Barnes Ultimate Swarms with Dr. -

Piers Morgan Outrage Over Brandpool Celebrity Trust Survey Submitted By: Friday's Media Group Monday, 19 April 2010

Piers Morgan outrage over Brandpool celebrity trust survey Submitted by: Friday's Media Group Monday, 19 April 2010 Piers Morgan has expressed outrage at being voted the sixth least trusted celebrity brand ambassador in a survey by ad agency and creative content providers Brandpool. Writing in his Mail On Sunday column, the Britain’s Got Talent judge questioned the logic of the poll, which named the celebrities the public would most and least trust as the faces of an ad campaign. But Brandpool has hit back at Morgan for failing to recognise the purpose of its research. Morgan, who also neglected to credit Brandpool as the source of the study, said: “No real surprises on the Most Trusted list, which is led by ‘national treasures’ such as David Attenborough, Stephen Fry, Richard Branson and Michael Parkinson. “As for the Least Trusted list, I find the logic of this one quite odd. Katie Price, for example, comes top, yet I would argue that she’s one of the most trustworthy people I know… Then I suddenly pop up at No 6, an outrage which perhaps only I feel incensed about. Particularly as that smiley little rodent Russell Brand slithers in at No 7. Making me supposedly less trustworthy than a former heroin junkie and sex addict.” Morgan was also surprised to see Simon Cowell, Cheryl Cole, Sharon Osbourne, Tom Cruise and Jonathan Ross in the Least Trusted list. However, he agreed with the inclusion of John Terry, Ashley Cole, Tiger Woods and Tony Blair, all of whom, he said, were “united by a common forked tongue”. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or microfiche but lack the clarity on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, 35mm slides of 6”x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography. Order Number 8717659 Art openings as celebratory tribal rituals Kelm, Bonnie G., Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1987 Copyright ©1987 by Kelm, Bonnie G. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

The Journal of the Association for Journalism Education

Journalism Education The Journal of the Association for Journalism Education Volume one, number one April 2012 Page 2 Journalism Education Volume 1 number 1 Journalism Education Journalism Education is the journal of the Association for Journalism Education a body representing educators in HE in the UK and Ireland. The aim of the journal is to promote and develop analysis and understanding of journalism education and of journalism, particu- larly when that is related to journalism education. Editors Mick Temple, Staffordshire University Chris Frost, Liverpool John Moores University Jenny McKay Sunderland University Stuart Allan, Bournemouth University Reviews editor: Tor Clark, de Montfort University You can contact the editors at [email protected] Editorial Board Chris Atton, Napier University Olga Guedes Bailey, Nottingham Trent University David Baines, Newcastle University Guy Berger, Rhodes University Jane Chapman, University of Lincoln Martin Conboy, Sheffield University Ros Coward, Roehampton University Stephen Cushion, Cardiff University Susie Eisenhuth, University of Technology, Sydney Ivor Gaber, Bedfordshire University Roy Greenslade, City University Mark Hanna, Sheffield University Michael Higgins, Strathclyde University John Horgan, Irish press ombudsman. Sammye Johnson, Trinity University, San Antonio, USA Richard Keeble, University of Lincoln Mohammed el-Nawawy, Queens University of Charlotte An Duc Nguyen, Bournemouth University Sarah Niblock, Brunel University Bill Reynolds, Ryerson University, Canada Ian Richards, University -

Life on Air: Memoirs of a Broadcaster PDF Book

LIFE ON AIR: MEMOIRS OF A BROADCASTER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sir David Attenborough | 448 pages | 01 Jul 2011 | Ebury Publishing | 9781849900010 | English | London, United Kingdom Life on Air: Memoirs of a Broadcaster PDF Book And not all of us can do that, even given the chance; I, for one, most certainly could not, given my insects phobia. Featuring 60 superb color plates, this is an easy-to-use photographic identification guide to the You'll like it if you like Sir. In his compelling autobiography, Michael McIntyre reveals all. I will defiantly listen to another of his marvellous books. For additional information, see the Global Shipping Program terms and conditions - opens in a new window or tab This amount includes applicable customs duties, taxes, brokerage and other fees. Why on earth you would think they are quartz crystals? Attenborough's storytelling powers are legendary, and they don't fail him as he recounts how he came to stand in rat-infested caves in Venezuela, confront wrestling crocodiles, abseil down a rainforest tree in his late sixties, and wake with the lioness Elsa sitting on his chest. This is a big old book, or at least it felt it to me. He was knighted in and now lives near London. As a student of film it is a veritable history of broadcast television and practical film making. If you are not happy then neither are we. Rediscover the thrills, grandeur, and unabashed fun of the Greek myths. David Attenborough is a giant of natural history and this book charting his many TV series brought home to me just what a contribution he's made to our understanding of the natural world. -

Sir David Attenborough Trounces Young Stars in Brandpool's Celebrity Trust Poll

Sir David Attenborough trounces young stars in Brandpool’s celebrity trust poll Submitted by: Friday's Media Group Friday, 9 April 2010 Sir David Attenborough trounces young stars in Brandpool’s celebrity trust poll Sir David Attenborough is the celebrity consumers would most trust as the figurehead for an advertising campaign, according to a survey commissioned by ad agency and creative content providers Brandpool. However, it was Katie Price who narrowly beat John Terry and Ashley Cole to be voted the least believable brand ambassador, followed by Amy Winehouse, Heather Mills, Tiger Woods and Tony Blair – the latter raising questions over Labour’s deployment of its former leader as a ‘secret weapon’ in the run-up to the election. The survey flies in the face of the Cebra study published last week by research agency Millward Brown, which indexed the appeal of celebrities in relation to certain brands. But Brandpool’s research suggests the popularity of young stars such as David Tennant, Cheryl Cole and David Beckham doesn’t always translate into trust. The poll saw 46% of respondents name Sir David as one of their top three choices, with Stephen Fry second on 36% and Richard Branson third on 20%. It was the elder statesmen of British broadcasting who dominated the top 10, with Michael Parkinson, Sir Terry Wogan, Sir David Dimbleby, Jeremy Paxman, Lord Alan Sugar and Jeremy Clarkson also highly rated. These silver-haired stars were favoured despite almost a third of respondents being under 35. And although an even split of men and women voted, the only female celebrity in the top 10 was The One Show presenter Christine Bleakley. -

Aggression and Symbols of Power

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 10-14-1990 Aggression and symbols of power Karen Kuhn Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Kuhn, Karen, "Aggression and symbols of power" (1990). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rochester Institute of Technology A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Fine and Applied Arts in Candidacy for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Aggression and Symbols of Power by Karen Kuhn 10.14.90 Approvals Advisor: Mark Stanitz Date: /.¥yl1l. Associate Advisor: Leonard Urso Date: /:.~/(?/?~ . Associate Advisor: David Dickenson Date: I.~/~.f/..~(J. Special Assistant to the Dean for Graduate Affairs: Philip Bornarth Date: !~E(!1.9. Peter Grofeeler I, Karen V. Kuhn, prefer to be contacted each time a request for reproduction is made. I can be reached at the following address: 10 Valdepenas Lane Clifton Park. NY 12065 Date: 90.10.14 Aggression and Symbols of Power Abstract: Weapons are one of the oldest and most significant forms of artifacts, occurring in virtually all human cultures. Weapons and their technology often determine power structures, not only by brute force of arms, but by long standing respect to ritual aggression. In many cultures, weapons have become abstracted and formalized to become symbols of power and authority, as in a ruler 's scepter, which is a glorified war club. -

Ben Newth AMPS Head of Audio

Ben Newth AMPS Head of Audio 1 Springvale Terrace, W14 0AE 37-38 Newman Street, W1T 1QA 44-48 Bloomsbury Street, London, WC1B 3QJ Tel: 0207 605 1700 [email protected] Drama Cyberbully - RTS and BAFTA Nominee 'Best Single Drama' 1 x 90' RAW TV for Channel 4 The People Next Door 1 x 60' RAW TV for Channel 4 UKIP: The First 100 Days 1 x 90' RAW TV for Channel 4 Blackout 1 x 90' RAW TV for Channel 4 American Blackout 1 x 90’ RAW TV for National Geographic Hard Tide 1 x 90' Deerstalker Films Blackbird - BAFTA Scotland Nominee 'Audience Award' 1 x 90’ Deerstalker Films Mermaids 1 x 90’ Darlow Smithson for Animal Planet I Shouldn’t Be Alive 14 x 60’ Darlow Smithson for Animal Planet & ITV Playhouse Presents: The Call Out 1 x 30’ Sprout Pictures for Sky Arts Playhouse Presents: Foxtrot 1 x 30’ Sprout Pictures for Sky Arts Drijfzand 1 x 90' Pieter van Huistee for NED Ticket to Jerusalem 1 x 90' Argus Films Ford Transit 1 x 90' Augustus Films Comedy The Life of Rock with Brian Pern 2 x 30' BBC Comedy for BBC Two Boom Town 6 x 30' Knickerbockerglory for BBC Three A Bear's Tale 6 x 30' Bellyache Productions for Channel 4 Documentary: Factual Heathrow: Britain's Busiest Airport 2 x 50' RAW TV for ITV Alex Jones: Fertility and Me 1 x 60' BBC Scotland for BBC One Celebrity Troll Trackers 1 x 50' Popkorn for C5 Dr Jeff: Rocky Mountain Vet 6 x 60' Double Act for Discovery Miss Transgender UK 1 x 60' Minnow Films for BBC Three and BBC One Body Hack: Metal Gear Man 2 x 15' BBC Three Rest in Pixels 1 x 30' BBC Three Stephen Fry in Central America 3 x -

Model Decision Notice and Advice

Reference: FS50150782 Freedom of Information Act 2000 (Section 50) Decision Notice Date: 25 March 2008 Public Authority: British Broadcasting Corporation (‘BBC’) Address: MC3 D1 Media Centre Media Village 201 Wood Lane London W12 7TQ Summary The complainant requested details of payments made by the BBC to a range of personalities, actors, journalists and broadcasters. The BBC refused to provide the information on the basis that the information was held for the purposes of journalism, art and literature. Having considered the purposes for which this information is held, the Commissioner has concluded that the requested information was not held for the dominant purposes of journalism, art and literature and therefore the request falls within the scope of the Act. Therefore the Commissioner has decided that in responding to the request the BBC failed to comply with its obligations under section 1(1). Also, in failing to provide the complainant with a refusal notice the Commissioner has decided that the BBC breached section 17(1) of the Act. However, the Commissioner has also concluded that the requested information is exempt from disclosure by virtue of section 40(2) of the Act. The Commissioner’s Role 1. The Commissioner’s duty is to decide whether a request for information made to a public authority has been dealt with in accordance with the requirements of Part 1 of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (the “Act”). In the particular circumstances of this complaint, this duty also includes making a formal decision on whether the BBC is a public authority with regard to the information requested by the complainant. -

BBC Group Annual Report and Accounts 2018/19

BBC Group Annual Report and Accounts 2018/19 BBC Group Annual Report and Accounts 2018/19 Laid before the National Assembly for Wales by the Welsh Government Return to contents © BBC Copyright 2019 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Photographs are used ©BBC or used under the terms of the PACT agreement except where otherwise identified. Permission from copyright holders must be sought before any photographs are reproduced. You can download this publication from bbc.co.uk/annualreport Designed by Emperor emperor.works Prepared pursuant to the BBC Royal Charter 2016 (Article 37) Return to contents OVERVIEW Contents About the BBC 2 Inform, Educate, Entertain 4 Highlights from the year p.2 6 Award-winning content Strategic report 8 A message from the Chairman About the BBC 10 Director-General’s statement 16 Delivering our creative remit Highlights from the year and 18 – Impartial news and information award-winning content 22 – Learning for people of all ages 26 – Creative, distinctive, quality output 34 – Reflecting the UK’s diverse communities 48 – Reflecting the UK to the world 55 Audiences and external context 56 – Audience performance and market context 58 – Performance by Service 61 – Public Service Broadcasting expenditure p.8 62 – Charitable work -

'Good Evening from a Hut Near Chelmsford'

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | FEBRUARY-MARCH 2020 ‘Good evening from a hut near Chelmsford’ Modest beginnings for British broadcasting Contents Main feature 12 Radio Shack Britains first ‘wireless’ station News he media is changing so fast that 03 BBC plans major cuts few jobs stay the same and unfortunately journalists cannot Corporation to axe 450 jobs always rely on the work they know best 04 Watchdog probes magazine takeover continuing throughout their careers. Major deal under investigation TDiversifying is a way of protecting yourself against a changing landscape and we have two 05 Newsquest withdraws cuts threat features on that subject. Move follows Scottish strike vote Neil Merrick speaks to journalists who made positive starts 06 Broadcasting authority refuses to act after being made redundant or leaving local newspapers by Anger over bans on journalists setting up their own local news websites. And Ruth Addicott finds out what it takes to succeed in media training, a pursuit “which can be a lucrative and useful sideline. Features As news and journalism rapidly reshapes, it’s also interesting 14 Earning from learning to look back at much earlier innovations in the media. Jonathan Media training can be lucrative Sale traces the very early beginnings of radio which began in a small hut near Chelmsford. 16 Growth on the home turf Meanwhile there has been a key victory in the NUJ’s long- Local news sites thriving running campaign on equal pay at the BBC with the ruling by an employment tribunal that Samira Ahmed should receive Regulars pay parity with Jeremy Vine. -

Strategies Used by the Far Right to Counter Accusations of Racism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bournemouth University Research Online Strategies used by the far right to counter accusations of racism SIMON GOODMAN Coventry University [email protected] ANDREW J JOHNSON Bournemouth University [email protected] Abstract This paper addresses the way in which the leader of the far-right British National Party (BNP), Nick Griffin, attempts to present the party as non-racist during hostile media appearances. The process of ‘fascism recalibration’, in which the party attempts to present itself in a more moderate way, which has been used to account for its electoral gain, is discussed. A discursive analytical approach is applied to one television and two radio programmes, all on the BBC, in which Nick Griffin was interviewed. The paper addresses the question: ‘how is the BNP presented in a way that makes it appear reasonable and achieve ‘fascism recalibration’? Analysis identified three strategies employed for this objective. These are: the party is presented as (1) acting as a moderating force, whereby a favourable distinction is made between the BNP and both other extremists and the BNP's own past; (2) acting in minority groups’ best interests, where BNP policies are presented as being both supported by, and aimed to aid, minority groups; and (3) only opposing minority groups because of their own prejudices, a strategy used to justify Islamaphobia based on the supposed intolerances of Islam. The implications and limitations of these strategies are discussed. Key words: British National Party; Racism denial; Far-right; Islamophobia; Discourse analysis Acknowledgements The authors would like to thanks Dr.