Narrative Integration in 16-Bit Video Game Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TESIS: Grand Theft Auto IV. Impacto Y Contexto En Los Videojuegos Como

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO FACULTAD DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES ACATLÁN Grand Theft Auto IV. Impacto y contexto en los videojuegos como parte de la cultura de masas Tesis para obtener el título de: Licenciado en Comunicación PRESENTA David Mendieta Velázquez ASESOR DE TESIS Mtro. José C. Botello Hernández UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. Grand Theft Auto IV Impacto y contexto en los videojuegos como parte de la cultura de masas Agradecimientos A mis padres. Gracias, papá, por enseñarme valores y por tratar de enseñarme todo lo que sabías para que llegara a ser alguien importante. Sé que desde el cielo estás orgulloso de tu familia. Mamá, gracias por todo el apoyo en todos estos años; sé que tu esfuerzo es enorme y en este trabajo se refleja solo un poco de tus desvelos y preocupaciones. Gracias por todo tu apoyo para la terminación de este trabajo. A Ariadna Pruneda Alcántara. Gracias, mi amor, por toda tu ayuda y comprensión. Tu orientación, opiniones e interés que me has dado para la realización de cualquier proyecto que me he propuesto, así como por ser la motivación para seguir adelante siempre. -

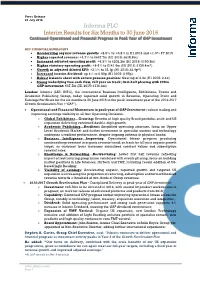

Informa PLC Interim Results for Six Months to 30 June 2016 Continued Operational and Financial Progress in Peak Year of GAP Investment

Press Release 28 July 2016 Informa PLC Interim Results for Six Months to 30 June 2016 Continued Operational and Financial Progress in Peak Year of GAP investment KEY FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Accelerating organic revenue growth: +2.5% vs +0.2% in H1 2015 and +1.0% FY 2015 Higher reported revenue: +4.7% to £647.7m (H1 2015: £618.8m) Increased adjusted operating profit: +6.3% to £202.2m (H1 2015: £190.3m) Higher statutory operating profit: +8.6% to £141.6m (H1 2015: £130.4m*) Growth in adjusted diluted EPS: +3.1% to 23.1p (H1 2015: 22.4p*) Increased interim dividend: up 4% to 6.80p (H1 2015: 6.55p) Robust balance sheet with secure pension position: Gearing of 2.4x (H1 2015: 2.4x) Strong underlying free cash flow, full year on track; first-half phasing with £20m GAP investment: £67.7m (H1 2015: £116.4m) London: Informa (LSE: INF.L), the international Business Intelligence, Exhibitions, Events and Academic Publishing Group, today reported solid growth in Revenue, Operating Profit and Earnings Per Share for the six months to 30 June 2016 in the peak investment year of the 2014-2017 Growth Acceleration Plan (“GAP”). Operational and Financial Momentum in peak year of GAP Investment – robust trading and improving earnings visibility in all four Operating Divisions: o Global Exhibitions…Growing: Benefits of high quality Brand portfolio, scale and US expansion delivering continued double-digit growth; o Academic Publishing…Resilient: Simplified operating structure, focus on Upper Level Academic Market and further investment in specialist content -

Focus: the Communication Arts, Part 2. INSTITUTION Virginia Association of Teachers of English

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 046 CS 200 931 AUTHOR Wimer, Frances, Ed. TITLE Focus: The Communication Arts, Part 2. INSTITUTION Virginia Association of Teachers of English. PUB DATE 73 NOTE 66p. JOURNAL CIT Virginia English Bulletin; v23 n2 Entire Issue Winter 1973 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$3.15 DESCRIPTORS Authors; College Freshmen; *Communication Skills; *Composition (Literary); Drama; *English Instruction; Language Skills; Literature; Reading Instruction; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods; Teaching Techniques ABSTRACT The articles and authors featured in this issue are: "Preparing for Future Shock in English and Reading Instruction" by James R. Squire, "Great Expectations: Communicative Arts in the High School; or, Resetting the Clocks" by R. W. Reising and R. J. Rundus, "Some Expectations in English for College Freshmen" by May Jane Tillman, "The Role of the English Teacher in English Instruction" by Joseph E. Mahony, "Poor Fluency: A Communications Impasse," by Jan A. Guffin, "Composition: Task Competencies" by Charles K. Stallard, "Drama and Experimental Teaching" by Jane Schisgall, "Language Disabilities" by Blanche Hope Smith, "Syntactic Symmetry: Balance on the English Sentence" by Donald Nemanich, "Games Pupils Play," by Julia L. Shields, and "Great English Teaching Ideas" by Robert C. Small, Jr.(LL) U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. VOLUME =II NUMBER 2 WINTER1973 EDUCATION & WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY Virginia English $ Bullerin "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS COPY- RIGHTED MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY VIRGINIA ASSOCIATION OF TEACHERS OF ENGLISH Virginia Association o Teachers of English TO ERIC AND ORGANIZATIONS OPERATING UNDER AGREEMENTS WITH THE NATIONAL IN- STITUTE OF EDUCATION. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

EXTENDED FICTION in GAME DESIGN Austin Anderson (Michael Young) Department of Computer Science

University of Utah UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL UNMASKING THE PLAYER: EXTENDED FICTION IN GAME DESIGN Austin Anderson (Michael Young) Department of Computer Science INTRODUCTION In any story, an element being diegetic means that it is an element of the story that the characters of the fiction can sense. The simplest example is that of music in a movie; if there is a radio playing music in the scene, that music is diegetic. If a musical soundtrack plays over the scene but is something the characters cannot hear, it is non-diegetic(DIEGETIC). The border between the diegetic and non-diegetic is most commonly referred to as “the fourth wall” (Webster), in reference to the imaginary fourth wall of a play set, where the sides and back of the room that events are taking place in are fully represented on the theater stage, but the opening through which the audience observes the events of the play is an imaginary barrier. This barrier isn’t just literally a completion of the four walls in a traditional room of a building, but also metaphorically separates the reality from the fiction, quarantining both from each other as to not interfere. The problem with this boundary is that it can’t fully encompass the medium of video games. Video games, at their very essence, are an interactive medium. They require some breach of the fourth wall for them to function, as the game could not proceed to tell its story without a player’s input, which is an addressing of the audience due to the necessity of their action. -

Mémoire FX Surinx Lire La Peur Dans Leur Jeu. Exploration Du Potentiel

https://lib.uliege.be https://matheo.uliege.be Lire la peur dans leur jeu. Exploration du potentiel effrayant du texte dans le jeu vidéo Auteur : Surinx, François-Xavier Promoteur(s) : Dozo, Björn-Olav Faculté : Faculté de Philosophie et Lettres Diplôme : Master en langues et lettres françaises et romanes, orientation générale, à finalité spécialisée en analyse et création de savoirs critiques Année académique : 2019-2020 URI/URL : http://hdl.handle.net/2268.2/10602 Avertissement à l'attention des usagers : Tous les documents placés en accès ouvert sur le site le site MatheO sont protégés par le droit d'auteur. Conformément aux principes énoncés par la "Budapest Open Access Initiative"(BOAI, 2002), l'utilisateur du site peut lire, télécharger, copier, transmettre, imprimer, chercher ou faire un lien vers le texte intégral de ces documents, les disséquer pour les indexer, s'en servir de données pour un logiciel, ou s'en servir à toute autre fin légale (ou prévue par la réglementation relative au droit d'auteur). Toute utilisation du document à des fins commerciales est strictement interdite. Par ailleurs, l'utilisateur s'engage à respecter les droits moraux de l'auteur, principalement le droit à l'intégrité de l'oeuvre et le droit de paternité et ce dans toute utilisation que l'utilisateur entreprend. Ainsi, à titre d'exemple, lorsqu'il reproduira un document par extrait ou dans son intégralité, l'utilisateur citera de manière complète les sources telles que mentionnées ci-dessus. Toute utilisation non explicitement autorisée ci-avant (telle que par exemple, la modification du document ou son résumé) nécessite l'autorisation préalable et expresse des auteurs ou de leurs ayants droit. -

Console Games in the Age of Convergence

Console Games in the Age of Convergence Mark Finn Swinburne University of Technology John Street, Melbourne, Victoria, 3122 Australia +61 3 9214 5254 mfi [email protected] Abstract In this paper, I discuss the development of the games console as a converged form, focusing on the industrial and technical dimensions of convergence. Starting with the decline of hybrid devices like the Commodore 64, the paper traces the way in which notions of convergence and divergence have infl uenced the console gaming market. Special attention is given to the convergence strategies employed by key players such as Sega, Nintendo, Sony and Microsoft, and the success or failure of these strategies is evaluated. Keywords Convergence, Games histories, Nintendo, Sega, Sony, Microsoft INTRODUCTION Although largely ignored by the academic community for most of their existence, recent years have seen video games attain at least some degree of legitimacy as an object of scholarly inquiry. Much of this work has focused on what could be called the textual dimension of the game form, with works such as Finn [17], Ryan [42], and Juul [23] investigating aspects such as narrative and character construction in game texts. Another large body of work focuses on the cultural dimension of games, with issues such as gender representation and the always-controversial theme of violence being of central importance here. Examples of this approach include Jenkins [22], Cassell and Jenkins [10] and Schleiner [43]. 45 Proceedings of Computer Games and Digital Cultures Conference, ed. Frans Mäyrä. Tampere: Tampere University Press, 2002. Copyright: authors and Tampere University Press. Little attention, however, has been given to the industrial dimension of the games phenomenon. -

Best Wishes to All of Dewey's Fifth Graders!

tiger times The Voice of Dewey Elementary School • Evanston, IL • Spring 2020 Best Wishes to all of Dewey’s Fifth Graders! Guess Who!? Who are these 5th Grade Tiger Times Contributors? Answers at the bottom of this page! A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R Tiger Times is published by the Third, Fourth and Fifth grade students at Dewey Elementary School in Evanston, IL. Tiger Times is funded by participation fees and the Reading and Writing Partnership of the Dewey PTA. Emily Rauh Emily R. / Levine Ryan Q. Judah Timms Timms Judah P. / Schlack Nathan O. / Wright Jonah N. / Edwards Charlie M. / Zhu Albert L. / Green Gregory K. / Simpson Tommy J. / Duarte Chaya I. / Solar Phinny H. Murillo Chiara G. / Johnson Talula F. / Mitchell Brendan E. / Levine Jojo D. / Colledge Max C. / Hunt Henry B. / Coates Eve A. KEY: ANSWER KEY: ANSWER In the News Our World............................................page 2 Creative Corner ..................................page 8 Sports .................................................page 4 Fun Pages ...........................................page 9 Science & Technology .........................page 6 our world Dewey’s first black history month celebration was held in February. Our former principal, Dr. Khelgatti joined our current Principal, Ms. Sokolowski, our students and other artists in poetry slams, drumming, dancing and enjoying delicious soul food. Spring 2020 • page 2 our world Why Potatoes are the Most Awesome Thing on the Planet By Sadie Skeaff So you know what the most awesome thing on the planet is, right????? Good, so you know that it is a potato. And I will tell you why the most awesome thing in the world is a potato, and you will listen. -

Annual Copyright License for Corporations

Responsive Rights - Annual Copyright License for Corporations Publisher list Specific terms may apply to some publishers or works. Please refer to the Annual Copyright License search page at http://www.copyright.com/ to verify publisher participation and title coverage, as well as any applicable terms. Participating publishers include: Advance Central Services Advanstar Communications Inc. 1105 Media, Inc. Advantage Business Media 5m Publishing Advertising Educational Foundation A. M. Best Company AEGIS Publications LLC AACC International Aerospace Medical Associates AACE-Assn. for the Advancement of Computing in Education AFCHRON (African American Chronicles) AACECORP, Inc. African Studies Association AAIDD Agate Publishing Aavia Publishing, LLC Agence-France Presse ABC-CLIO Agricultural History Society ABDO Publishing Group AHC Media LLC Abingdon Press Ahmed Owolabi Adesanya Academy of General Dentistry Aidan Meehan Academy of Management (NY) Airforce Historical Foundation Academy Of Political Science Akademiai Kiado Access Intelligence Alan Guttmacher Institute ACM (Association for Computing Machinery) Albany Law Review of Albany Law School Acta Ecologica Sinica Alcohol Research Documentation, Inc. Acta Oceanologica Sinica Algora Publishing ACTA Publications Allerton Press Inc. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae Allied Academies Inc. ACU Press Allied Media LLC Adenine Press Allured Business Media Adis Data Information Bv Allworth Press / Skyhorse Publishing Inc Administrative Science Quarterly AlphaMed Press 9/8/2015 AltaMira Press American -

Foundations for Music-Based Games

Die approbierte Originalversion dieser Diplom-/Masterarbeit ist an der Hauptbibliothek der Technischen Universität Wien aufgestellt (http://www.ub.tuwien.ac.at). The approved original version of this diploma or master thesis is available at the main library of the Vienna University of Technology (http://www.ub.tuwien.ac.at/englweb/). MASTERARBEIT Foundations for Music-Based Games Ausgeführt am Institut für Gestaltungs- und Wirkungsforschung der Technischen Universität Wien unter der Anleitung von Ao.Univ.Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr.techn. Peter Purgathofer und Univ.Ass. Dipl.-Ing. Dr.techn. Martin Pichlmair durch Marc-Oliver Marschner Arndtstrasse 60/5a, A-1120 WIEN 01.02.2008 Abstract The goal of this document is to establish a foundation for the creation of music-based computer and video games. The first part is intended to give an overview of sound in video and computer games. It starts with a summary of the history of game sound, beginning with the arguably first documented game, Tennis for Two, and leading up to current developments in the field. Next I present a short introduction to audio, including descriptions of the basic properties of sound waves, as well as of the special characteristics of digital audio. I continue with a presentation of the possibilities of storing digital audio and a summary of the methods used to play back sound with an emphasis on the recreation of realistic environments and the positioning of sound sources in three dimensional space. The chapter is concluded with an overview of possible categorizations of game audio including a method to differentiate between music-based games. -

Living Faith Lutheran Church Presents

Living Faith Lutheran Church Presents THE WASHINGTON METROPOLITAN GAMER SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Nigel Horne, Music Director Living Faith Lutheran Church Rockville, Md. April 26, 2014, 2 p.m. WMGSO.org | @MetroGSO | Facebook.com/WMGSO [Classical Music. Game On.] Concert Program Gusty Garden Galaxy Mahito Yokota Super Mario Galaxy (2007) arr. Robert Garner Twilight Princess Toru Minegishi, Asuka Ota, The Legend of Zelda: Koji Kondo Twilight Princess (2006) arr. Robert Garner, Katie Noble Dancing Mad Nobuo Uematsu Final Fantasy VI (1994) arr. Alexander Ryan Objection! Masakazu Sugimori, Phoenix Wright: Ace Naoto Tanaka Attorney (2001) arr. Alexander Ryan Kid Icarus Hirokazu Tanaka Kid Icarus (1987) arr. Alyssa Menes Dämmerung Yasunori Mitsuda Xenosaga Episode I: Der Wille arr. Chris Apple zur Macht (2003) Castles Koji Kondo, David Wise Super Mario World (1990), The arr. Chris Apple Legend of Zelda: Link to the Past (1991), Donkey Kong Country 2 (1995), Super Mario Bros. (1985) Pokémedley Junichi Masuda, Pokémon: The Animated Series John Siegler, Go Ichinose (1998), Pokémon: Red/Blue arr. Chris Lee, Robert Garner, (1998), Pokémon: White/Black Doug Eber (2011) Roster Flute Flugelhorn Tenor Voice Jessie Biele Robert Garner Darin Brown Jessica Robertson Sheldon Zamora-Soon Trombone Oboe Eric Fagan Bass Voice David Shapiro Steve O’Brien Alexander Booth Matthew Harker Clarinet Concert Percussion Alisha Bhore Joshua Rappaport Violin Jessica Elmore Zara Simpson Victoria Chang Lee Stearns Matthew Costales Bass Clarinet Van Stottlemyer Lauren Kologe Yannick -

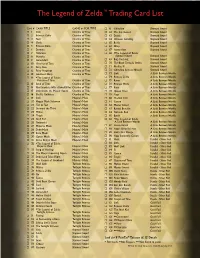

The Legend of Zelda™ Trading Card List

The Legend of Zelda™ Trading Card List Card # CARD TITLE GAME or FOIL TYPE ¨ 61 Ghirahim Skyward Sword ¨ 1 Link Ocarina of Time ¨ 62 The Imprisoned Skyward Sword ¨ 2 Princess Zelda Ocarina of Time ¨ 63 Demise Skyward Sword ¨ 3 Navi Ocarina of Time ¨ 64 Crimson Loftwing Skyward Sword ¨ 4 Sheik Ocarina of Time ¨ 65 Beetle Skyward Sword ¨ 5 Princess Ruto Ocarina of Time ¨ 66 Whip Skyward Sword ¨ 6 Darunia Ocarina of Time ¨ 67 Scattershot Skyward Sword ¨ 7 Twinrova Ocarina of Time ¨ 68 *The Legend of Zelda: ¨ 8 Morpha Ocarina of Time Skyward Sword Skyward Sword ¨ 9 Ganondorf Ocarina of Time ¨ 69 Bug Catching Skyward Sword ¨ 10 Ocarina of Time Ocarina of Time ¨ 70 The Black Tornado Strikes Skyward Sword ¨ 1 1 Fairy Bow Ocarina of Time ¨ 7 1 Finding Fi Skyward Sword ¨ 12 Fairy Slingshot Ocarina of Time ¨ 72 Ghirahim Reveals Himself Skyward Sword ¨ 13 Goddess’s Harp Ocarina of Time ¨ 73 Link A Link Between Worlds ¨ 14 *The Legend of Zelda: ¨ 74 Princess Zelda A Link Between Worlds Ocarina of Time Ocarina of Time ¨ 75 Ravio A Link Between Worlds ¨ 15 Song of Time Ocarina of Time ¨ 76 Princess Hilda A Link Between Worlds ¨ 16 First Encounter With a Powerful Foe Ocarina of Time ¨ 77 Irene A Link Between Worlds ¨ 17 Link Draws the Master Sword Ocarina of Time ¨ 78 Queen Oren A Link Between Worlds ¨ 18 Sheik’s Guidance Ocarina of Time ¨ 79 Yuga A Link Between Worlds ¨ 19 Link Majora’s Mask ¨ 80 Shadow Link A Link Between Worlds ¨ 20 Happy Mask Salesman Majora’s Mask ¨ 8 1 Ganon A Link Between Worlds ¨ 2 1 Tatl & Tael Majora’s Mask ¨ 82 Master Sword