HUMAN STREETS the Mayor’S Vision for Cycling, Three Years On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kings Cross to Liverpool Street Via 13 Stations Walk

Saturday Walkers Club www.walkingclub.org.uk Kings Cross to Liverpool Street via 13 stations walk All London’s railway terminals, the three royal parks, the River Thames and the City Length 21.3km (13.3 miles) for the whole walk, but it is easily split into smaller sections: see Walk Options below Toughness 1 out of 10 - entirely flat, but entirely on hard surfaces: definitely a walk to wear cushioned trainers and not boots. Features This walk links (and in many cases passes through) all thirteen London railway terminals, and tells you something of their history along the way. But its attractions are not just limited to railway architecture. It also passes through the three main Central London parks - Regent’s Park, Hyde Park/Kensington Gardens and St James's Parks - and along the Thames into and through the City of London*. It takes in a surprising number of famous sights and a number of characteristic residential and business areas: in fact, if you are first time visitor to London, it is as good an introduction as any to what the city has to offer. Despite being a city centre walk, it spends very little of its time on busy roads, and has many idyllic spots in which to sit or take refreshment. In the summer months you can even have an open air swim midway through the walk in Hyde Park's Serpentine Lido. (* The oldest part of London, now the financial district. Whenever the City, with a capital letter, is used in this document, it has this meaning.) Walk Being in Central London, you can of course start or finish the walk wherever Options you like, especially at the main railway stations that are its principal feature. -

Conferences & Events

CONFERENCES & EVENTS WELCOME TO LONDON HILTON ON PARK LANE As one of the most famous hotels in the world, London Hilton on Park Lane is synonymous with outstanding service, excellence and style. Situated in the heart of Mayfair, the hotel offers stunning views of Hyde Park and the Capital’s skyline from all guest rooms. London Hilton on Park Lane has hosted many of the city’s landmark events over the years. Everyone from kings to presidents, Hollywood nobility to the International Olympic Committee have passed through our doors. Our experience in event management ensures that no matter what the occasion, from high profile parties to intimate gatherings, the event is a success. LOCATION In the Heart of London London Hilton on Park Lane is located on Park Lane, Mayfair, overlooking attractions such as Buckingham Palace and Hyde Park and just a short walk from the shopping districts of Knightsbridge, Bond Street and Oxford Street. Hyde Park Corner and Green Park tube stations are close by and there is an excellent local bus service. We are just a 10-minute taxi ride from either the Gatwick Express or the Heathrow Express. OXFORD STREET BOND NEW BOND ST STREET MARBLE MAYFAIR ARCH PARK LANE HYDE PARK PICCADILLYGREEN PARK HYDE PARK KNIGHTSBRIDGE CORNER BUCKINGHAM BELGRAVIA PALACE AT A GLANCE OUR ROOMS EAT & DRINK OUT & ABOUT GUEST ROOMS GALVIN AT WINDOWS • Overlooking Hyde Park Located on floors 5 to 11, these bright and airy RESTAURANT & BAR • Moments from Buckingham Palace rooms enjoy stunning views across Hyde Park Located on the 28th Floor, Michelin-starred • Explore Oxford Street, Bond Street and and Knightsbridge. -

The Biscuit – Autumn 2020

Autumn 2020 Issue 7 Norwegian A PIECE OF SCANDINAVIA Hood IN SE16 ARTIST VOCALIST SCIENTIST BECOME AN -IST SPECIALIST APPLY SHORT COURSES NOW! at MORLEY COLLEGE LONDON ONLINE ONLINE + IN CENTRE AUTUMN 2020 CONTENTS 24 - 25 Editor’s Letter Laura Burgoine ear readers, so many community groups and We haven’t been ghosting you, services sprang into action to take Dwe promise! We’d offer a note care of our elderly and vulnerable from the Prime Minister to explain neighbours. So it’s no surprise that as our absence but you’ve heard enough we find ourselves in October, there of the c-word for one year. is still plenty to tell you about. Local It’s with great pleasure I bring you authors have been writing, designers the return of the Biscuit! If 2020 has have been making, and foodies shown us anything, it’s how adaptable have been baking. Now more than y’all are! Restaurants became grocery ever, we’re connecting to our own stores and delivery services, churches neighbourhoods – we’ve got all sorts live-streamed their masses, events of local gems for you right here. got postponed or streamed, fitness These are your stories; thank you instructors switched to Zoom, and for sharing them. 22 26 About us Editor Laura Burgoine Going out, out What’s on in real life… and the virtual world 5 Writers Michael Holland, Debra Gosling, Cara Cummings, John Kelly People 8-9 Photography Christian Fisher Norwegian Church chaplains on a Mission Marketing Tammy Jukes, Anthony Phillips Design Dan Martin, Lizzy Tweedale Art & Design Screen-prints, tatts and swimwear -

World War One Interactive Map Press Release

PRESS RELEASE from The Herne Hill Society World War One Interactive Map A joint venture by the Herne Hill Society, Dulwich Society and other local groups to commemorate the centenary of World War One. The Herne Hill Society, with the Dulwich Society and the Friends of Norwood Cemetery, has launched an online interactive map to commemorate the centenary of World War One. So far the map features nearly 50 locations in the Herne Hill, Dulwich and Norwood. More will be added. It can be seen at http://tiny.cc/ww1-interactive-map The online map indicates the contribution the area made to the war effort, as well as the impact on the lives of local people. For example, it is not generally known that in 1917 German Gotha aircraft dropped bombs in Dulwich Village, killing two people. Other sites include a school where girls decided to forego their school prizes and use the money to buy wool and knit clothes for soldiers at the Front. There were the Wellcome Laboratories on Brockwell Park (now demolished) where scientific research led to serums and vaccines that saved the lives of countless soldiers. The Sunray Estate of post-War ‘Homes Fit for Heroes’ is there, as are the military hospitals set up at King’s College, the Maudsley and East Dulwich. A number of attacks on shops with German-sounding names are pin- pointed, together with a petition from residents of Frankfurt Road in Herne Hill to change the name of their 'Germanic' street – and much more. The map, built with Google’s MapEngine, also features many war memorials, with over 2,200 names of servicemen associated with this small part of South London who were killed in World War One. -

New Southwark Plan Preferred Option: Area Visions and Site Allocations

NEW SOUTHWARK PLAN PREFERRED OPTION - AREA VISIONS AND SITE ALLOCATIONS February 2017 www.southwark.gov.uk/fairerfuture Foreword 5 1. Purpose of the Plan 6 2. Preparation of the New Southwark Plan 7 3. Southwark Planning Documents 8 4. Introduction to Area Visions and Site Allocations 9 5. Bankside and The Borough 12 5.1. Bankside and The Borough Area Vision 12 5.2. Bankside and the Borough Area Vision Map 13 5.3. Bankside and The Borough Sites 14 6. Bermondsey 36 6.1. Bermondsey Area Vision 36 6.2. Bermondsey Area Vision Map 37 6.3. Bermondsey Sites 38 7. Blackfriars Road 54 7.1. Blackfriars Road Area Vision 54 7.2. Blackfriars Road Area Vision Map 55 7.3. Blackfriars Road Sites 56 8. Camberwell 87 8.1. Camberwell Area Vision 87 8.2. Camberwell Area Vision Map 88 8.3. Camberwell Sites 89 9. Dulwich 126 9.1. Dulwich Area Vision 126 9.2. Dulwich Area Vision Map 127 9.3. Dulwich Sites 128 10. East Dulwich 135 10.1. East Dulwich Area Vision 135 10.2. East Dulwich Area Vision Map 136 10.3. East Dulwich Sites 137 11. Elephant and Castle 150 11.1. Elephant and Castle Area Vision 150 11.2. Elephant and Castle Area Vision Map 151 11.3. Elephant and Castle Sites 152 3 New Southwark Plan Preferred Option 12. Herne Hill and North Dulwich 180 12.1. Herne Hill and North Dulwich Area Vision 180 12.2. Herne Hill and North Dulwich Area Vision Map 181 12.3. Herne Hill and North Dulwich Sites 182 13. -

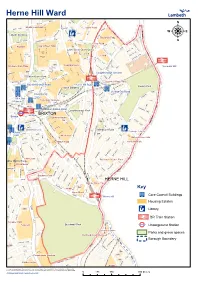

Herne Hill Ward AY VEW RO C B G O D R U OA M PS R O TA R N L D D L T S a YN T OST N O

Herne Hill Ward AY VEW RO C b G O D R U OA M PS R O TA R N L D D L T S A YN T OST N O M R S A T M T E L R M A PL E A W R R L N O Myatts Field South R S O K O OAD RT A T Paulet Road T E R R U C B A D E P N N N R T E LO C L A C R L L E D T D R A T S R U R E K E R B I L O E B N E H PE A L NFO U A L C R D M W D A S D T T A P A Y N A R A W Slade Gardens R O N V E C O E A K R K D L A D P H C L Thorlands TMO A RO R AD B UGH ORD O EET RO LILF ROA U TR HBO D R S G K RT OU E SA L M B T N C O M R S D I A B A A N L U L O E SPICE E Lilford Road D R R R D R : T E A Y E T D O C R CLOSE E A R R N O O Angell Town TMO Sch R S A S T M C A Robsart Y L O T E A E A I V D R L N D R W E C F A R O E R E O L V T A I L R T O F L N D A Elam Street Open Space D N E L R V E R AC O A PL O FERREY O R B D H A U O R N A S U D TO MEWS G A I AY T Sch N D L O D A H I C WYNNE T D L K Hertford E B A W N O W O E E V R L I N RD SERENADERS Lilford R GR L O A R N A Y E P N O T A MEWS E M N A O R S A E U O W D S S U K S W R M T I S O C N T R G E A G K L X B O T L R A H E W K ROAD R A P U A K R O D R O E S L A DN O U D D G F R O O A D B R V L A Sch U A U X G Loughborough O H H D R R A Stockwell Park TMO AN D D N A GE F S L O Denmark Hill L E T L S R A R O T T E Y E L L T C H RK R E E A A O Y S R OAD L P A B VILLA R EL S D R G O G N M D D U N E M R Sch A RD A N D R A E G L R S D W L L R A O Y S L SE M A Loughborough Junction UM B S E R E F T D D N Y N W E R C F E R C O I S A H D E E I A L R M T C C D D T S U W B Max Roach Park R R R I O G N A P D A I D F G S T 'S O D A N N H E S -

Mayfair Area Guide

Mayfair Area Guide Living in Mayfair • Mayfair encompasses the area situated between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly and Park Lane, in the very heart of London’s West End, and adjacent to St James’s and its glorious Royal parks to the south. Overview • For over 300 years, Mayfair and St James’s have provided grand homes, luxury goods and services to the aristocracy. The area is characterised by its splendid period architecture, beautiful shop fronts, leading art galleries, auction houses, wine merchants, cosmopolitan restaurants, 5 star hotels and gentleman’s clubs. Did You Know • Mayfair is named after an annual 15 day long May Fair that took place on the site that is now Shepherd Market, from 1686 until 1764. • There is a disused tube station on Down Street that used to serve the Piccadilly line. It was closed in 1932 and was later used by Winston Churchill as an underground bunker during the Second World War. • No. 50 Berkeley Square is said to be the most haunted house in London, so much so that it will give any psychic an electric shock if they touch the external brickwork. • Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II was born in a house on Bruton Street and lived in Mayfair during her infancy. Her future husband Prince Philip had his stag night at The Dorchester. • The oldest outdoor statue in London is located above the entrance of Sotheby’s on New Bond Street. The Ancient Egyptian effigy of the lion-goddess Sekmet is carved from black igneous rock and dates to around 1320 BC. -

Towards a Cultural Geography of Modern Memorials Andrew M

Architecture and Interpretation Essays for Eric Fernie Edited by Jill A. Franklin, T. A. Heslop & Christine Stevenson the boydell press Architecture.indb 3 21/08/2012 13:06 © Contributors 2012 All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2012 The Boydell Press, Woodbridge isbn 978-184383-781-7 The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk ip12 3df, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. 668 Mount Hope Ave, Rochester, ny 14620-2731, USA website: www.boydellandbrewer.com A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library The publisher has no responsibility for the continued existence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate Papers used by Boydell & Brewer Ltd are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in sustainable forests Designed and typeset in Adobe Arno Pro by David Roberts, Pershore, Worcestershire Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, cr0 4yy Architecture.indb 4 21/08/2012 13:06 Towards a Cultural Geography of Modern Memorials Andrew M. Shanken t is virtually impossible to move through a European or I American city without passing memorials that prompt us – if we notice them at all – merely to scratch at some fading memory. -

Lordship Lane, Dulwich, SE22 £253 Per Week

Dulwich 94 Lordship Lane London SE22 8HF Tel: 020 8299 6066 [email protected] Lordship Lane, Dulwich, SE22 £253 per week (£1,100 pcm) Fees apply 1 bedroom, 1 Bathroom Preliminary Details Bushells are pleased to present this stunning modern apartment to the market. This property consists of one double bedroom with inbuilt storage, a sunny reception room with a Juliet balcony and large enough for a dining area, fully fitted kitchen with appliances including a washer/dryer and a modern bathroom suite. Trains: East Dulwich West Dulwich Peckham Rye Nunhead Denmark Hill Queens Road Herne Hill and Tulse Hill all have British Rail Stations which run to either London Bridge Victoria or Blackfriars. Key Features • Modern Apartment • Inbuilt storage • Washer/dryer • Large reception • Modern bathroom • Juliet balcony Dulwich | 94 Lordship Lane, London, SE22 8HF | Tel: 020 8299 6066 | [email protected] 1 Area Overview There are a number of recognised districts in Dulwich, namely Dulwich Village, East and West Dulwich. Dulwich Village contains the original shopping street and still contains nearly all of its original 18th and 19th century building. It is a conservation zone and borders Dulwich Park where the Horse and Motor Show is held annually. Beauberry House is opposite the railway station and is a private house now housing a restaurant which has won accolades in 2009 and was named Best British Wedding Venue in 2010. © Collins Bartholomew Ltd., 2013 Nearest Stations Forest Hill (0.8M) Sydenham Hill (0.9M) West Dulwich (1.0M) Dulwich | 94 Lordship Lane, London, SE22 8HF | Tel: 020 8299 6066 | [email protected] 2 Energy Efficiency Rating & Environmental Impact (CO2) Rating Council Tax Bands Council Band A Band B Band C Band D Band E Band F Band G Band H Southwark £ 886 £ 1,034 £ 1,182 £ 1,330 £ 1,625 £ 1,920 £ 2,216 £ 2,659 Average £ 934 £ 1,060 £ 1,246 £ 1,401 £ 1,713 £ 2,024 £ 2,335 £ 2,803 Disclaimer Every care has been taken with the preparation of these Particulars but complete accuracy cannot be guaranteed. -

Times Are Changing at Sydenham Hill

This autumn, we’ll be running an amended weekday timetable shown below affecting Times are changing Off-Peak* metro services, but only on days when we expect the weather to be at its worst. at Sydenham Hill Check your journey up to 3 days in advance at southeasternrailway.co.uk/autumn Trains to London Mondays to Fridays There will be a minimum of 2 trains per hour Off-Peak, mainly at 18 and 48 minutes past the hour towards London. Sydenham Hill d 0518 0548 0618 0630 0650 0703 0710 0734 0740 0749 0803 0810 0817 0840 0847 0903 0910 0917 0933 0949 1003 1018 1048 1103 1118 1133 West Dulwich d 0520 0550 0620 0632 0652 0705 0712 — 0742 0752 0806 0812 0820 0842 0850 0905 0912 0920 0935 0951 1005 1020 1050 1105 1120 1135 Herne Hill a 0522 0552 0622 0634 0654 0707 0715 0737 0745 0754 0808 0815 0822 0845 0852 0907 0915 0922 0937 0953 1007 1022 1052 1107 1122 1137 Loughborough Jn d — — — — — — 0719 — 0749 — — 0819 — 0849 — — 0919 — — — — — — — — — Elephant & Castle d — — — — — — 0723 — 0753 — — 0823 — 0853 — — 0923 — — — — — — — — — London Blackfriars a — — — — — — 0729 — 0759 — — 0829 — 0859 — — 0929 — — — — — — — — — Brixton d 0526 0556 0626 0638 0658 0711 — 0741 — 0758 0812 — 0826 — 0856 0911 — 0926 0941 0957 1011 1026 1056 1111 1126 1141 London Victoria a 0535 0605 0635 0647 0707 0720 — 0750 — 0807 0821 — 0835 — 0905 0921 — 0935 0950 1004 1020 1033 1103 1118 1133 1148 Sydenham Hill d 1148 1218 1248 1518 1548 1603 1618 1648 1718 1733 1748 1803 1818 1833 1848 1918 1948 2018 2033 2048 2103 2118 2133 2148 West Dulwich d 1150 1220 1250 and at 1520 -

11 Sydenham Hill, Dulwich, London SE26 6SH 8 Exclusive Architect

11 Sydenham Hill, Dulwich, London SE26 6SH 8 exclusive architect designed apartments by Bespoke Homes 11 Sydenham Hill, Dulwich, London SE26 6SH 8 exclusive architect designed apartments A hand crafted project by Bespoke Homes Woodside Villa Woodside Villa Bespoke Homes Bespoke Homes creates great in the UK to offer a whole spaces that are exciting, range of selective services that dynamic and inspiring. Spaces allow many levels of personal and materials are deeply tailoring. This encompasses considered so that they are unique apartments, private one- practical, workable, enjoyable off houses, bespoke interiors and soulful, offering delight and crafted furniture, all of and maturity over time. Above which can be custom-made all we aspire for spaces and to individual briefs. buildings to be enjoyed by both the users of the building ‘Bespoke culture offers an and society. With this primary alternative for quality and ambition, our projects address design conscious individuals wider audiences, engaging who have exhausted the with issues including the traditional housing model and environment, new movements who are aware of the pitfalls in housing design and a practice of most new build housing.’ of high quality architecture. The Bespoke design approach Currently we have expanding embraces detail, craft, offices in London and invention and integrity with a Bespoke developments: Copenhagen with projects particularly strong emphasis The recent award winning developing both in the UK and on the use of natural materials DKH development. internationally. Bespoke Homes and daylight. Function and is also engaged with self-build, practicality are inherent, workspace and renovation. whilst each Bespoke space aims to be unique and set Bespoke Homes is a modern apart from the next by way of boutique service offering places the individual design process. -

Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists

Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists 27 Sussex Place, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RG Telephone: 02077726200 https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/contact-us/directions/ Travel information By rail From Marylebone station Marylebone station is a 10-minute walk from the College: Exit the station and turn left onto Melcombe Place Follow the road for 350m until you reach Baker Street Turn left and continue straight towards Regent’s Park Follow the road around to the left on to the Outer Circle Walk past the first entrance to Sussex Place until you reach the next entrance Turn left into Sussex Place and the College will be on your right. From Paddington station Take the Circle or Hammersmith & City line east to Baker Street tube station Follow the walking directions from Baker Street tube station (below). From Euston station Walk from Euston station to Euston Square underground station (5–10 minutes): o Take the exit on to Euston Road and turn right o Continue down the road until you turn left in to Gower Street o The undergound station will be on your left From Euston Square station, take the Hammersmith & City, Metropolitan or Circle line west to Baker Street underground station Follow the walking directions from Baker Street tube station (below). From King’s Cross St Pancras station Take the Hammersmith & City, Metropolitan or Circle line west to Baker Street underground station Follow the walking directions from Baker Street tube station (below). By tube/underground Baker Street is the nearest underground station, served by the Hammersmith & City, Bakerloo, Circle, Jubilee and Metropolitan lines.