Signed, Malraux Also by Jean-Frarn;Ois Lyotard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

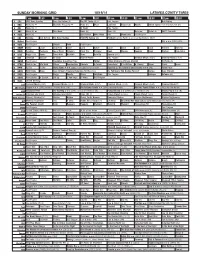

Sunday Morning Grid 10/19/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/19/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Meet LazyTown Poppy Cat Noodle Action Sports From Brooklyn, N.Y. (N) 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. ABC7 Presents 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Carolina Panthers at Green Bay Packers. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program I.Q. ››› (1994) (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Home Alone 4 ›› (2002, Comedia) French Stewart. -

PDF EPUB} Jasmine's War by Daniel Hyland Asia Ray

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Jasmine's War by Daniel Hyland Asia Ray. Dancer who was introduced to reality TV audiences as a competitor on Lifetime's Dance Moms. She became the star of the Lifetime series Raising Asia. She played Sydney Simpson on American Crime Story in 2016. Before Fame. She started dancing at age 2. She trained in figure skating and dance while growing up. Trivia. She has placed first on the Dance Moms episodes "Rock That," "Ready for War," and "The Robot." She played Jasmine in two episodes of Grey's Anatomy in 2016. She sang the national anthem at a Los Angeles Clippers game at the Staples Center. She performed on tour with Mariah Carey. Family Life. She has a younger sister named Bella Blu. Her parents are named Kristie Ray and Shawn Ray. Green Print. Edited As digital technology became integral to the capitalist market dystopia of the first decades of the 21st century, it refashioned both our ways of working and our ways of consuming, as well as. Green Print. About. Merlin Press has been publishing books for over 30 years. We cover wide variety of subjects and categories with our main focus being on social & political titles covering key issues that concern all of us. For further information visit the representation page, or contact our team. Contact. Contact: Customer Services. Merlin Press, Central Books Building 50 Freshwater Rd Chadwell Heath London RM8 1RX. Jasmine's War by Daniel Hyland. Automatic capture for your stadium has arrived. Hudl Focus Outdoor records, uploads and livestreams American football and soccer games. -

PICASSO Les Livres D’Artiste E T Tis R a D’ S Vre Li S Le PICASSO

PICASSO LES LIVRES d’ARTISTE The collection of Mr. A*** collection ofThe Mr. d’artiste livres Les PICASSO PICASSO Les livres d’artiste The collection of Mr. A*** Author’s note Years ago, at the University of Washington, I had the opportunity to teach a class on the ”Late Picasso.” For a specialist in nineteenth-century art, this was a particularly exciting and daunting opportunity, and one that would prove formative to my thinking about art’s history. Picasso does not allow for temporalization the way many other artists do: his late works harken back to old masterpieces just as his early works are themselves masterpieces before their time, and the many years of his long career comprise a host of “periods” overlapping and quoting one another in a form of historico-cubist play that is particularly Picassian itself. Picasso’s ability to engage the art-historical canon in new and complex ways was in no small part influenced by his collaborative projects. It is thus with great joy that I return to the varied treasures that constitute the artist’s immense creative output, this time from the perspective of his livres d’artiste, works singularly able to point up his transcendence across time, media, and culture. It is a joy and a privilege to be able to work with such an incredible collection, and I am very grateful to Mr. A***, and to Umberto Pregliasco and Filippo Rotundo for the opportunity to contribute to this fascinating project. The writing of this catalogue is indebted to the work of Sebastian Goeppert, Herma Goeppert-Frank, and Patrick Cramer, whose Pablo Picasso. -

Lasemaine.Fr2010 FLUP 15-18 Mars

lasemaine.fr2010 FLUP 15-18 mars Organisation : Ana Paula Coutinho Maria de Fátima Outeirinho José Domingues de Almeida ISBN: 978-972-8932-72-5 lasemaine.fr 2010 Table des matières Une semaine qui se poursuit 2 Dominique Viart - Littératures contemporaines française et francophones : divergences et convergences 4 Maria Hermínia Amado Laurel - Lectures d’écrivains : ‘vision du monde’ et référents littéraires dans la correspondance d’Alice Rivaz 34 Re(visões) de Camus em Portugal Marcello Duarte Mathias (Depoimento) Roberto Merino - Camus, o nosso contemporâneo 55 Maria Luísa Malato Borralho – Camus, a poltrona e a História ou três razões para ler Camus 57 Pedro Eiras- Lendo Camus – eu, visitante, um pouco ladrão 66 Écrit d’ici François Emmanuel – Où niche l’hibou? 73 La semaine à l’affiche Album lasemaine.fr 2010 Une semaine qui se poursuit S’inscrire dans les devoirs commémoratifs du calendrier sans pour autant succomber à la routine de la réédition pure et simple, telle est la gageure qu’ont essayé de tenir les Organisateurs de lasemaine.fr 2010. Il s’est agi, cette année, de mettre en relief plusieurs apports et voix qui illustrent la richesse de la production culturelle francophone contemporaine au sens large. Dès lors, une réflexion sur les complexes et improbables étanchéités du domaine littéraire hexagonal et de celui des espaces francophones pluriels s’imposait que Dominique Viart entreprend judicieusement. Une chose est sûre : les destins de ces deux perspectives géoculturelles du fait littéraire apparaissent intimement liés et devraient, à le lire, augurer d’un renouveau prometteur pour l’écriture narrative en langue française. -

Limited Editions Club

g g OAK KNOLL BOOKS www.oakknoll.com 310 Delaware Street, New Castle, DE 19720 Oak Knoll Books was founded in 1976 by Bob Fleck, a chemical engineer by training, who let his hobby get the best of him. Somehow, making oil refineries more efficient using mathematics and computers paled in comparison to the joy of handling books. Oak Knoll Press, the second part of the business, was established in 1978 as a logical extension of Oak Knoll Books. Today, Oak Knoll Books is a thriving company that maintains an inventory of about 25,000 titles. Our main specialties continue to be books about bibliography, book collecting, book design, book illustration, book selling, bookbinding, bookplates, children’s books, Delaware books, fine press books, forgery, graphic arts, libraries, literary criticism, marbling, papermaking, printing history, publishing, typography & type specimens, and writing & calligraphy — plus books about the history of all of these fields. Oak Knoll Books is a member of the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (ILAB — about 2,000 dealers in 22 countries) and the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America (ABAA — over 450 dealers in the US). Their logos appear on all of our antiquarian catalogues and web pages. These logos mean that we guarantee accurate descriptions and customer satisfaction. Our founder, Bob Fleck, has long been a proponent of the ethical principles embodied by ILAB & the ABAA. He has taken a leadership role in both organizations and is a past president of both the ABAA and ILAB. We are located in the historic colonial town of New Castle (founded 1651), next to the Delaware River and have an open shop for visitors. -

Y 2 0 ANDRE MALRAUX: the ANTICOLONIAL and ANTIFASCIST YEARS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University Of

Y20 ANDRE MALRAUX: THE ANTICOLONIAL AND ANTIFASCIST YEARS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Richard A. Cruz, B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1996 Y20 ANDRE MALRAUX: THE ANTICOLONIAL AND ANTIFASCIST YEARS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Richard A. Cruz, B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1996 Cruz, Richard A., Andre Malraux: The Anticolonial and Antifascist Years. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May, 1996, 281 pp., 175 titles. This dissertation provides an explanation of how Andr6 Malraux, a man of great influence on twentieth century European culture, developed his political ideology, first as an anticolonial social reformer in the 1920s, then as an antifascist militant in the 1930s. Almost all of the previous studies of Malraux have focused on his literary life, and most of them are rife with errors. This dissertation focuses on the facts of his life, rather than on a fanciful recreation from his fiction. The major sources consulted are government documents, such as police reports and dispatches, the newspapers that Malraux founded with Paul Monin, other Indochinese and Parisian newspapers, and Malraux's speeches and interviews. Other sources include the memoirs of Clara Malraux, as well as other memoirs and reminiscences from people who knew Andre Malraux during the 1920s and the 1930s. The dissertation begins with a survey of Malraux's early years, followed by a detailed account of his experiences in Indochina. -

Témoignage De Gaston Palewski

Témoignage de Gaston Palewski Gaston PALEWSKI « De Gaulle, la Grande-Bretagne et la France Libre 1940-1943 », Espoir n°43, juin 1983 Pour l’auditoire distingué qui m’écoute, le sujet de cette conférence : « De Gaulle, la Grande- Bretagne et la France Libre, de 1940 à 1943 », c’est-à-dire jusqu’au départ pour Alger et à la première mise en place des institutions provisoires en terre française, est connu dans tous ses détails. Les « Mémoires » du général de Gaulle et, tout dernièrement, le remarquable livre de François Kersaudy, en ont décrit l’atmosphère et indiqué les difficultés qui ont marqué cette période. Mais les historiens doivent fatalement s’abriter derrière les textes, les procès- verbaux, les documents qui font foi. Or ces documents révèlent tout, excepté l’essentiel, c’est- à-dire l’élément humain qui éclaire l’apparence et les dessous de l’action diplomatique et militaire. Peut-être le fait que j’ai été un témoin actif de la plupart de ses événements me permet-il d’esquisser l’étude de cet élément humain ? Je suis heureux de le faire ici, devant vous, dans ce Londres qui nous fut accueillant et que j’ai retrouvé avec beaucoup d’affection et d’émotion. J’ai rappelé déjà dans quelles conditions j’ai connu le colonel de Gaulle ; comment lors de notre premier contact chez Paul Reynaud, la vérité évidente de ses théories s’est imposée à moi et je me suis dit que je mettrais le peu d’influence dont je disposais au service de l’homme et de ses idées. -

XMAS DOUBLE NUMBER Nos. 6 & 7

XMAS DOUBLE NUMBER COTERIE NINA HAMNETT Nos. 6 & 7 Winter, 1920-21 COTERIE A Quarterly ART, PROSE, AND POETRY General Editor: Russell Green. American Editors: Conrad Aiken, South Yarmouth, Mass., U.S.A. Stanley I. Rypins, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minn., U.S.A. Editorial Committee: T. W. Earp. Aldous Huxley. Nina Hamnett. Literary and Art Contributions for publication in COTERIE should be addressed to the Editor, 66 Charing Cross Road, London, W.C.2; or in U.S.A. to the American Editors. All other communications should be addressed to Hendersons, 66 Charing Cross Road, London, W.C.2. Contributors who desire the return of rejected MSS. are requested to enclose a stamped addressed envelope. COTERIE is published Quarterly, price 2s. 8d., post free. Yearly subscription, 10s. 8d., post free. New York, U.S.A.: Copies may be purchased at Brentano's, price 75 cents; or yearly, $3. Paris: Copies may be had from W. H. Smith & Son, Rue de Rivoli. COTERIE NINA HAMNETT LONDON : HENDERSONS SIXTY-SIX CHARING CROSS ROAD COTERIE, Winter, 1920-21, Nos. 6 and 7 Xmas Double Number - COVER DESIGN by NINA HAMNETT I. John Burley: " Chop and Change " 6 II. Roy Campbell: Canal 23 The Head 23 The Sleepers 24 III. Wilfrid Rowland Childe: Hymn to the Earth 26 IF. Thomas Earp: Grand Passion 28 Post-mortem 28 Cowboy Bacchanale 29 V. Godfrey Elton: Farcical Rhyme 31 VI. John Gould Fletcher: The Star 32 Who will Mark 33- VII. Frank Harris: Akbar: The " Mightiest" 34 VIII. Russell Green : Gulliver 52 IX. G. H. Johnstone : Naive 58 X. -

L'aventure Littéraire Du Xxe Siècle DEUXIÈME ÉPOQUE 1920-1960

© 2008 AGI-Information Management Consultants May be used for personal purporses only or by Henri Lemaitre libraries associated to dandelon.com network. Ancien élève de l'Ecole Normale Supérieure Agrégé de l'Université, Docteur ès-lettres L'Aventure littéraire du XXe siècle DEUXIÈME ÉPOQUE 1920-1960 Collection Littérature Pierre Bordas et fils, éditeurs Table La crise des années vingt : Répercussions et réactions 11 Première partie L'exploration poétique 19 Chapitre 1 D'une époque à l'autre : la continuité lyrique 25 Paul Fort 26 Tristan Klingsor 28 L'expérience des fantaisistes (Paul-Jean Toulet, Tristan Derême, Francis Carco, Philippe Çhabanèix) 29 « Une vie chantée » : Marie-Noël 34 A la recherche d'un « pays natal » (René-Guy Cadou, Jean Follain) ... 37 Le lyrisme et l'obstacle (Alain Bosquet, Eugène Guillevic) 40 Un poète-carrefour : Jacques Prévert 45 Chapitre 2 IJ& rupture surréaliste 55 La tentation nihiliste et Dada (Tristan Tzara, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes) 57 André Breton et la révolution surréaliste 63 Les œuvres surréalistes (Paul Eluard, Benjamin Péret, Robert Desnos, René Crevel, André Breton, etc.) 101 Surréalisme et occultisme 115 Chapitre 3 De l'expérience surréaliste à la conversion lyrique 123 La crise du surréalisme 123 Le dégagement du lyrisme personnel : Robert Desnos 134 Le duo du lyrisme personnel et du lyrisme engagé : Louis Aragon et Paul Eluard 140 Chapitre 4 Le face-à-face de la poésie et du réel 155 Un poète exemplaire : Pierre Reverdy 155 Aux frontières de l'existence et de l'absence : Jules Supervielle 165 Du face-à-face au corps-à-corps et à l'exorcisme : Henri Michaux 170 L'écriture et les choses, l'écriture des choses : Francis Ponge 185 A la recherche d'une « connaissance productive du réel » : René Char . -

Who's Who at the Rodin Museum

WHO’S WHO AT THE RODIN MUSEUM Within the Rodin Museum is a large collection of bronzes and plaster studies representing an array of tremendously engaging people ranging from leading literary and political figures to the unknown French handyman whose misshapen proboscis was immortalized by the sculptor. Here is a glimpse at some of the most famous residents of the Museum… ROSE BEURET At the age of 24 Rodin met Rose Beuret, a seamstress who would become his life-long companion and the mother of his son. She was Rodin’s lover, housekeeper and studio helper, modeling for many of his works. Mignon, a particularly vivacious portrait, represents Rose at the age of 25 or 26; Mask of Mme Rodin depicts her at 40. Rose was not the only lover in Rodin's life. Some have speculated the raging expression on the face of the winged female warrior in The Call to Arms was based on Rose during a moment of jealous rage. Rose would not leave Rodin, despite his many relationships with other women. When they finally married, Rodin, 76, and Rose, 72, were both very ill. She died two weeks later of pneumonia, and Rodin passed away ten months later. The two Mignon, Auguste Rodin, 1867-68. Bronze, 15 ½ x 12 x 9 ½ “. were buried in a tomb dominated by what is probably the best The Rodin Museum, Philadelphia. known of all Rodin creations, The Thinker. The entrance to Gift of Jules E. Mastbaum. the Rodin Museum is based on their tomb. CAMILLE CLAUDEL The relationship between Rodin and sculptor Camille Claudel has been fodder for speculation and drama since the turn of the twentieth century. -

Turkish Foreign Policy Toward the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62)

Turkish Studies ISSN: 1468-3849 (Print) 1743-9663 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ftur20 Turkish Foreign Policy Toward the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62) Eyüp Ersoy To cite this article: Eyüp Ersoy (2012) Turkish Foreign Policy Toward the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62), Turkish Studies, 13:4, 683-695, DOI: 10.1080/14683849.2012.746440 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14683849.2012.746440 Published online: 13 Dec 2012. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 264 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ftur20 Download by: [Bilkent University] Date: 29 August 2017, At: 02:20 Turkish Studies, 2012 Vol. 13, No. 4, 683–695, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14683849.2012.746440 Turkish Foreign Policy Toward the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62) EYU¨ P ERSOY Department of International Relations, Bilkent University, Bilkent, Turkey ABSTRACT Turkish foreign policy toward the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62) was construed as persistent Turkish endorsement of official French positions generating abiding resentment among the states of the Third World, especially Arab states, and understandably in Algeria, which was to elicit backlashes from the Third World states thereafter consequently causing substantial complications in Turkish foreign policy. Stressing the importance of incor- porating nonmaterial and ideational factors in analyses of foreign policy, two arguments are put forward in this article for an accurate explanation of Turkish foreign policy toward Alger- ian War of Independence. First, it was the conception of the West, defined not only in strategic or military terms, but also in ideational and civilizational terms that induced Turkish policy- makers to adopt insular policies regarding Algeria. -

Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) and World War I France: Mobilizing Motherhood and the Good Suffering

Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) and World War I France: Mobilizing Motherhood and the Good Suffering By Anya B. Holland-Barry A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 08/24/2012 This dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Susan C. Cook, Professor, Music Charles Dill, Professor, Music Lawrence Earp, Professor, Music Nan Enstad, Professor, History Pamela Potter, Professor, Music i Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my best creations—my son, Owen Frederick and my unborn daughter, Clara Grace. I hope this dissertation and my musicological career inspires them to always pursue their education and maintain a love for music. ii Acknowledgements This dissertation grew out of a seminar I took with Susan C. Cook during my first semester at the University of Wisconsin. Her enthusiasm for music written during the First World War and her passion for research on gender and music were contagious and inspired me to continue in a similar direction. I thank my dissertation advisor, Susan C. Cook, for her endless inspiration, encouragement, editing, patience, and humor throughout my graduate career and the dissertation process. In addition, I thank my dissertation committee—Charles Dill, Lawrence Earp, Nan Enstad, and Pamela Potter—for their guidance, editing, and conversations that also helped produce this dissertation over the years. My undergraduate advisor, Susan Pickett, originally inspired me to pursue research on women composers and if it were not for her, I would not have continued on to my PhD in musicology.