Chapter 2 Types of Poisons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OECD Guidance Document Number 24: Acute Oral Toxicity Testing

Unclassified ENV/JM/MONO(2001)4 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 23-Jul-2001 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ English - Or. English ENVIRONMENT DIRECTORATE Unclassified ENV/JM/MONO(2001)4 JOINT MEETING OF THE CHEMICALS COMMITTEE AND THE WORKING PARTY ON CHEMICALS, PESTICIDES AND BIOTECHNOLOGY OECD SERIES ON TESTING AND ASSESSMENT Number 24 GUIDANCE DOCUMENT ON ACUTE ORAL TOXICITY TESTING English - Or. English JT00111082 Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d’origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format ENV/JM/MONO(2001)4 2 ENV/JM/MONO(2001)4 OECD Environment, Health and Safety Publications Series on Testing and Assessment No 24 GUIDANCE DOCUMENT ON ACUTE ORAL TOXICITY TESTING Environment Directorate ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT Paris June 2001 3 ENV/JM/MONO(2001)4 Also published in the Series on Testing and Assessment No. 1, Guidance Document for the Development of OECD Guidelines for Testing of Chemicals (1993; reformatted 1995) No. 2, Detailed Review Paper on Biodegradability Testing (1995) No. 3, Guidance Document for Aquatic Effects Assessment (1995) No. 4, Report of the OECD Workshop on Environmental Hazard/Risk Assessment (1995) No. 5, Report of the SETAC/OECD Workshop on Avian Toxicity Testing (1996) No. 6, Report of the Final Ring-test of the Daphnia magna Reproduction Test (1997) No. 7, Guidance Document on Direct Phototransformation of Chemicals in Water (1997) No. 8, Report of the OECD Workshop on Sharing Information about New Industrial Chemicals Assessment (1997) No. 9, Guidance Document for the Conduct of Studies of Occupational Exposure to Pesticides During Agricultural Application (1997) No. -

Biological Toxins As the Potential Tools for Bioterrorism

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Biological Toxins as the Potential Tools for Bioterrorism Edyta Janik 1, Michal Ceremuga 2, Joanna Saluk-Bijak 1 and Michal Bijak 1,* 1 Department of General Biochemistry, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, University of Lodz, Pomorska 141/143, 90-236 Lodz, Poland; [email protected] (E.J.); [email protected] (J.S.-B.) 2 CBRN Reconnaissance and Decontamination Department, Military Institute of Chemistry and Radiometry, Antoniego Chrusciela “Montera” 105, 00-910 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +48-(0)426354336 Received: 3 February 2019; Accepted: 3 March 2019; Published: 8 March 2019 Abstract: Biological toxins are a heterogeneous group produced by living organisms. One dictionary defines them as “Chemicals produced by living organisms that have toxic properties for another organism”. Toxins are very attractive to terrorists for use in acts of bioterrorism. The first reason is that many biological toxins can be obtained very easily. Simple bacterial culturing systems and extraction equipment dedicated to plant toxins are cheap and easily available, and can even be constructed at home. Many toxins affect the nervous systems of mammals by interfering with the transmission of nerve impulses, which gives them their high potential in bioterrorist attacks. Others are responsible for blockage of main cellular metabolism, causing cellular death. Moreover, most toxins act very quickly and are lethal in low doses (LD50 < 25 mg/kg), which are very often lower than chemical warfare agents. For these reasons we decided to prepare this review paper which main aim is to present the high potential of biological toxins as factors of bioterrorism describing the general characteristics, mechanisms of action and treatment of most potent biological toxins. -

AN INTRODUCTION to AQUATIC TOXICOLOGY This Page Intentionally Left Blank ÂÂ an INTRODUCTION to AQUATIC TOXICOLOGY

AN INTRODUCTION TO AQUATIC TOXICOLOGY This page intentionally left blank AN INTRODUCTION TO AQUATIC TOXICOLOGY MIKKO NIKINMAA Professor of Zoology, Department of Biology, Laboratory of Animal Physiology, University of Turku, Turku, Finland AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Academic press is an imprint of Elsevier Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford, OX5 1GB, UK 225 Wyman Street, Waltham, MA 02451, USA Copyright © 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangement with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. -

(Vol 1): in Vitro Cytotoxicity Test Methods for Estimating Acute Oral

In Vitro Cytotoxicity Test Methods for Estimating Acute Oral Systemic Toxicity Background Review Document Volume 1 of 2 Prepared by The National Toxicology Program (NTP) Interagency Center for the Evaluation of Alternative Toxicological Methods (NICEATM) National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) P.O. Box 12233 Mail Drop: EC-17 Research Triangle Park, NC 27709 November 2006 NIH Publication No. 07-4518 National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences National Institutes of Health U.S. Public Health Service Department of Health and Human Services This document is available electronically at: http://iccvam.niehs.nih.gov/methods/invitro.htm Printed: 11/30/2006 In Vitro Cytotoxicity Test Methods BRD Table of Contents November 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDICES.................................................................................................................. xiii LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... xvi LIST OF TABLES...........................................................................................................xvii LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ...........................................................xx ACKNOWLEDGMENTS................................................................................................ xxv PREFACE........................................................................................................................xxix EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................... -

The Dose Makes the Poison

CHAPTER 1 THE DOSE MAKES THE POISON hich would you prefer to drink—a cup of caffeine or a cup of trichloroethylene? Chances are good that your response was “caf- Wfeine.” Caffeine occurs naturally in coffee, tea, and chocolate, and it is added to sodas and other types of drinks and foods. Trichloroethylene, on the other hand, is a solvent used to dissolve grease, and it is also a common ingredient in glues, paint removers, and cleaning fluids. Trichloroethylene does not occur naturally in the environment, but it is sometimes found as a pollut- ant in groundwater and surface water. So, which would be better to drink? Believe it or not, caffeine is more poisonous than trichloroethylene. At low concentrations, caffeine is used as a food additive because of its effects as a stimulant—it helps people to stay awake and to feel lively. However, at concentrations higher than those found in food products, caffeine can cause insomnia, dizziness, headaches, vomit- ing, and heart problems. In studies of laboratory animals, high doses of caf- feine have caused birth defects and cancer. Does this mean you should think twice about reaching for that cup of Toxicity indicates cocoa or tea? No, there’s more to the story than that. What it does mean is how poisonous a that many common substances found in food and drinks are toxic, or poison- substance is to ous, if you eat or drink large enough quantities. The amount of caffeine in a biological organisms. normal human diet does not cause illness, but just 50 times this amount is enough to be fatal. -

Method of Rough Estimation of Median Lethal Dose (Ld50)

b Meta olis g m & ru D T o f x o i Journal of Drug Metabolism and l c a o n l o r Saganuwan, J Drug Metab Toxicol 2015, 6:3 g u y o J Toxicology DOI: 10.4172/2157-7609.1000180 ISSN: 2157-7609 Research Article Open Access Arithmetic-Geometric-Harmonic (AGH) Method of Rough Estimation of Median Lethal Dose (Ld50) Using Up – and – Down Procedure *Saganuwan Alhaji Saganuwan Department of Veterinary Physiology, Pharmacology and Biochemistry, College Of Veterinary Medicine, University Of Agriculture, P.M.B. 2373, Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria *Corresponding author: Saganuwan Alhaji Saganuwan, Department of Veterinary Physiology, Pharmacology and Biochemistry, College Of Veterinary Medicine, University Of Agriculture, P.M.B. 2373, Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria, Tel: +2348027444269; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: April 6,2015; Accepted date: April 29,2015; Published date: May 6,2015 Copyright: © 2015 Saganuwan SA . This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Earlier methods adopted for the estimation of median lethal dose (LD50) used many animals (40 – 100). But for the up – and – down procedure, 5 – 15 animals can be used, the number I still consider high. So this paper seeks to adopt arithmetic, geometric and harmonic (AGH) mean for rough estimation of median lethal dose (LD50) using up – and – down procedure by using 2 – 6 animals that may likely give 1 – 3 reversals. The administrated doses should be summed up and the mean, standard deviation (STD) and standard error of mean (SEM) should be determined. -

Small Dose... Big Poison

Traps for the unwary George Braitberg Ed Oakley Small dose... Big poison All substances are poisons; Background There is none which is not a poison. It is not possible to identify all toxic substances in a single The right dose differentiates a poison from a remedy. journal article. However, there are some exposures that in Paracelsus (1493–1541)1 small doses are potentially fatal. Many of these exposures are particularly toxic to children. Using data from poison control centres, it is possible to recognise this group of Poisoning is a frequent occurrence with a low fatality rate. exposures. In 2008, almost 2.5 million human exposures were reported to the National Poison Data System (NPDS) in the United Objective States, of which only 1315 were thought to contribute This article provides information to assist the general to fatality.2 The most common poisons associated with practitioner to identify potential toxic substance exposures in children. fatalities are shown in Figure 1. Polypharmacy (the ingestion of more than one drug) is far more common. Discussion In this article the authors report the signs and symptoms Substances most frequently involved in human exposure are shown of toxic exposures and identify the time of onset. Where in Figure 2. In paediatric exposures there is an over-representation clear recommendations on the period of observation and of personal care products, cleaning solutions and other household known fatal dose are available, these are provided. We do not discuss management or disposition, and advise readers products, with ingestions peaking in the toddler age group. This to contact the Poison Information Service or a toxicologist reflects the acquisition of developmental milestones and subsequent for this advice. -

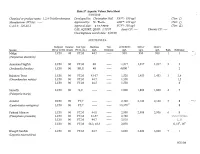

Rule 57 Aquatic Values Data Sheet 5/19/2010 Chemical Or Product Name

Rule 57 Aquatic Values Data Sheet 5/19/2010 Chemical or product name: 1,2,4-Trichlorobenzene Developed by: Christopher Hull FAV*: 850ug/l (Tier: l) Manufacturer (WTAs): Approved by: 1>. IS~;~ AMV*: 420 ug/l (Tier: l) C.A.S #: 120-82-1 Approval date: '/;J../"P-<>10 FCV*: 130 ug/l (Tier: !1) CAS, AQUIRE, QSAR: 1/12/10 Acute CF: ---- Chronic CF: ---- Clearinghouse search date: 6/20/96 ACUTE DATA Endpoint Duration Test Type Hardness Test LC50/EC50 SMAV GMAV Species (EC or LC50) (hours) (FT.M, etc.) mg!L Chemical ug/L ug/L ug/L Rank Reference ~ Midge LC50 48 FT,M 44.7 930 930 930 I I - (Tanytarsus dissimilis) American Flagfish LC50 96 FT,M 48 1,217 1,217 1,217 2 2 (Jordanellafloridae) LC50 96 SR,U 48 4,000 I 2 Rainbow Trout LC50 96 FT,M 43-57 1,520 1,453 1,453 "~ 3,4 (Oncorhynchus mykiss) LC50 96 FT,M 44.7 1,320 1,5 LC50 96 FT,M 44.5 1,530 6 Stonefly LC50 96 s,u 1,800 1,800 1,800 4 7 (Peltoperla maria) Annelid EC50 96 FT,? 2,140 2,140 2,140 5 8 (Lumbriculus variegatus) LC50 96 FT,? >3,370 2 8 Fathead Minnow LC50 96 FT,M 44.0 2,990 2,906 2,906 6 9 (Pimephales promelas) LC50 96 FT,M 43-57 2,760 4. 7.10.11 ~ .1 23,13,14 LC50 96 FT,M 44.7 3,010 I, 5 LC50 96 FT,M 56.3, 45.5 2,870 6, 153, 163 Bluegill Sunfish LC50 96 FT,M 44.7 3,020 3,020 3,020 7 I (Lepomis macrochirus) 9/21104 Crayfish LC50 96 FT,M 44.7 3,020 3,020 3,020 8 I (Orconectes immunis) Snail LC50 96 FT,M 44.7 3,160 3,160 3,160 9 I (Aplexus hypnorum) Cnidarian EC50 96 FT,? >3,370 >3,370 >3,370 10 8 (Hydra oligactis) LC50 96 FT,? >3,370 8 Water Flea EC50 48 FT,M 44.7 3,390 3,390 3,390 11 -

Health Impact of Dioxins

ⅥTopics Health Impact of Dioxins JMAJ 45(7): 312–315, 2002 Osamu WADA Professor, Department of Hygiene and Preventive Medicine, Saitama Medical School Key words: Dioxin; Toxity; Carcinogenicity; TCDD; Risk Dioxins, as well as endocrine disrupters, are this low dose, dioxins have the reputation of a group of chemicals that have received wide- being deadly poisonous. However, although spread publicity on a daily basis as new environ- the dose of 1g/kg body weight per day, i.e. mental pollutants. They are routinely described one thousandth of a gram appears small, it is as “deadly poisons and the most potent carcino- not so small when viewed from another stand- gens” resulting in fear and anxiety in the public point. It is one million times greater than 1 pg at the mention of dioxins. and 250,000 times greater than 4 pg/kg, the Various animal studies have shown that the daily intake of dioxins in the public. lethal dose median (LD50) of dioxins in guinea pigs is 1 g/kg body weight, indicating that the General Toxicity of Dioxin in Humans estimated toxicity of dioxins is 60,000 times higher than that of potassium cyanide. Long- An epidemiological study has been con- term animal studies with dioxins have also ducted recently in those involved in the acci- demonstrated its carcinogenicity, teratogenic- dental explosion at an agricultural chemical ity, immunotoxicity, and reproductive toxicity. plant in Seveso, Italy, workers in the agricul- These data certainly indicate that dioxins are tural chemical manufacturing industry, and deadly poisons. Vietnam veterans, in order to investigate the The concentration of dioxins is extremely acute and chronic effects of dioxin exposure. -

Toxicity and Hazard of Pesticides

Pesticide Toxicity and Hazard April, 2017 Introduction Pesticide applicators should understand the hazards and risks associated with the pesticides they use. Pesticides vary greatly in toxicity. Toxicity depends on the chemical and physical properties of a substance, and may be defined as the quality of being poisonous or harmful to animals or plants. Pesticides have many different modes of action, but in general cause biochemical changes which interfere with normal cell functions. The toxicity of any compound is related to the dose. A highly toxic substance causes severe symptoms of poisoning with small doses. A substance with a low toxicity generally requires large doses to produce mild symptoms. Even common substances like coffee or salt become poisons if large amounts are consumed. Toxicity can be either acute or chronic. Acute toxicity is the ability of a substance to cause harmful effects which develop rapidly following exposure, i.e. a few hours or a day. Chronic toxicity is the ability of a substance to cause adverse health effects resulting from long-term exposure to a substance. There is a great range in the toxicity of pesticides to humans. The relative hazard of a pesticide is dependent upon the toxicity of the pesticide, the dose and the length of time exposed. The hazard in using a pesticide is related to the likelihood of exposure to harmful amounts of the pesticide. The toxicity of a pesticide can’t be changed but the risk of exposure can be reduced with the use of proper personal protective equipment (PPE), proper handling and application procedures. Pesticide Toxicity Some pesticides are dangerous after one large dose (acute toxicity). -

Acute Toxicity Testing Without Animals: More Scientific and Less of a Gamble

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 3-2005 Acute Toxicity Testing Without Animals: More Scientific and Less of a Gamble Gillian R. Langley British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/appamet Part of the Bioethics and Medical Ethics Commons, Design of Experiments and Sample Surveys Commons, and the Laboratory and Basic Science Research Commons Recommended Citation Langley, G. (2005). Acute toxicity testing without animals. London, UK: BUAV. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Acute Toxicity Testing Without Animals ~ “more scientific and less of a gamble” Report by Dr Gill Langley MA PhD MIBiol CBiol March 2005 British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV) 16a Crane Grove London N7 8NN United Kingdom Email: [email protected] Web: www.buav.org Contents Foreword 3 1. Introduction 4 2. The Case Against Acute Toxicity Tests on Animals 5 2.1 Human relevance of acute toxicity tests on animals 6 2.2 Reliability of acute toxicity tests on animals 9 2.3 Practicalities of acute toxicity testing on animals 10 2.4 Animal suffering in acute toxicity tests 11 3. Classification and Labelling 11 4. High-throughput Prioritisation – Not Mass Animal Testing 12 5. Existing Data, Read-across and (Q)SARs for Acute Toxicity 13 5.1 Existing data 14 5.2 Read-across 14 5.3 (Q)SARs 15 6. Non-Animal Tests for Acute Toxicity 15 6.1 Rapid screening for acute toxicity 16 6.2 Fuller assessment for acute toxicity 17 6.2.1 Absorption in vitro and in silico 18 6.2.2 Plasma levels and target organ effects in vitro 19 6.2.3 Metabolism in vitro 20 6.2.4 Toxicokinetic modelling 20 7. -

The Calculation of Median Lethal Dose (LD50) and Maximum Permissible Dose (MPD) Values of Sodium Arsenite in Female Swiss Albino Mice

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 12, Issue 9 Ver. I (September. 2018), PP 89-91 www.iosrjournals.org The Calculation of Median Lethal Dose (LD50) And Maximum Permissible Dose (MPD) Values of Sodium Arsenite In Female Swiss Albino Mice *Shailendra Kumar And Preety Sinha Departement of Zoology, A. N. College, Patna, Bihar, India. Corresponding Author: Shailendra Kumar Abstract: Sodium arsenite is an environmental pollutant and is responsible for both knowing poisonings and accidental exposures that can cause harmful health issues and possibly death. Median lethal dose (LD50) is a statistically obtained dose of a compound that can be predicted to cause death in 50% of the mice when administered by a specific route as a single dose and mice noticed for a specific time period. In the present research, different doses i.e., 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21 and 24 mg/kg body weight of Sodium arsenite was given orally by gavage method to the seven different groups of Swiss albino mice. Signs and symptoms of toxicity and probable death of mice were observed for 3 hours and then at 6, 12, 24, 48 and 72 hours to calculate the Median lethal dose (LD50) and maximum permissible dose (MPD) of Sodium arsenite. The LD50 was found to 18 mg/kg body weight after oral administration in Swiss albino mice. Finally, MPD of Sodium arsenite by oral route in mice was found to be 1.8 mg/kg body weight. Keywords: Sodium arsenite, Swiss albino mice, LD50, MPD ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission: 27-08-2018 Date of acceptance: 11-09-2018 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- I.