Arrow #37 V16jwr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Document Analysis Questions

Captain John L. Anderson Document Analysis Instructions (2 image analysis and 2 SOAPS document analysis tools) Document Instructions Biography Read aloud, highlight significant information (who, what, when, and where) Document 1 How many steamboats? Anderson Steamboat Co. Ferry Schedule How many sailings? How many places does it travel? What does this document say about the Lake Washington steamboat business? What does this document say about the people who used the steamboats? What does this document say about transportation in general? Document 2 Complete image analysis graphic organizer Photograph of Anderson Shipyards 1908 Document 3 Complete image analysis graphic organizer Photograph of Anderson Shipyards 1917 Document 4 Complete SOAPS document analysis graphic organizer News article from Lake Washing- ton Reflector 1918 Document 5 Complete SOAPS document analysis graphic organizer News article from East Side Jour- nal 1919 How did the lowering of Lake Summarize all of the evidence you found in the documents. Washington impact Captain Anderson? Positive Negative Ferry Fay Burrows Document Analysis Instructions (2 image analysis and 3 SOAPS document analysis tools) Documents Instructions Biography Read aloud, highlight significant information (who, what, when, and where) Document 1 1. Why did Captain Burrows start a boat house? Oral History of Homer Venishnick Grandson of Ferry Burrows 2. How did he make money with the steam boat? 3. What fueled this ship? 4. What routes did Capt. Burrows take the steamboat to earn money? 5. What happened to the steamboat business when the lake was lowered? 6. What happened to North Renton when the lake was lowered? Document 2 1. What does “driving rafts” mean and how long did it take? Interview with Martha Burrows Hayes 2. -

The Reporter

TheReporter Volume76 lssue3 The Newsletterof the WaupocaHistorical Society Summer2072 WHSBoard of Directors:Dennis Lear, PresidenU Mike Kirk, Vice President; Betty Stewart, Secretary; BobKessler, Treasurer, Dick Bidwell, Tracy Behrendt, Gerald Chappell, Glenda Rhodes, Deb Fenske, DavidTrombla, Joyce Woldt, Don Writt, and MargeWritt WHSDirector: Julie Hintz HutchinsonHouse Museum Curator:Barbara Fay Wiese WaupocaYellowstone Troil Sociabilifi Tour !, Firct, ComeAll YeeWHS Memberc for o doy of sociolizingwith the WoupocaOld TimeAuto Clubmembers. Join us in celebratingthe 7W yeoronniversory of thefounding of the first highwayocross northern U. S.A. Theplan is thot ot noonon SundoySeptember 9th you can join/park in o clossiccor showot the WoupocoCity Square. Bring o picnicor pick up lunchot o localrestouront. At approximalely1:00 p. m. the carswill departfrom CitySquare olong the famous YellowstoneTrail to trovel to the HeritogeVillage of the PortogeCounty Historical Societyin Plover,Wisconsin. Maps of the tour route will be givenout neor the bondstondat the City Squorebetween noon ond 7 p. m. on Sept.th, ond oheodof time ot our Anntgl MembershipMeeting on Sept.6h. Thehistoric buitdings of the HeritageVittoge ii Ploverwitt be openfor visitotionon theofternoon of the gth.See the enclosedqrticle to review the historyof the trail ond Waupoca'sexciting involvement in makingit o reolity. AnnualWaupaca Historical Society Membership Meeting to be Held on September6th Second,Come AllYee WHS Members to attendthe annualmembership meeting on Thursday September6th, at 6:00p. m. at the HollyHistory Center. The meeting will beginon the main floorwith a specialskit entitled "l Havea Question".The skit will focus on the manyresources that WHShas available to our membersand to the generalpublic. A shortbusiness meeting will follow,with a reportfrom our treasurer,and announcements of upcomingevents. -

Arrow #11 Nottabloid.Cdr

April Number 2006 The Arrow 11 Official Publication of The Yellowstone Trail Association “A Good Road from Plymouth Rock to Puget Sound” Trailman of the year Major Effort to Mark the YT and Promote Seven On March 18 a small but hardy group of Yellowstone Trail Small Communities Association members gathered to honor the Trailman of the Year, As we mentioned in our last Arrow, seven small communities Michael Koerner of Appleton, WI. Michael is an outstanding strung along 40 miles of the Yellowstone Trail in central Wisconsin researcher. He has documented the location of the Yellowstone recently banned together for the purpose of promotion and Trail in detailed and meticulous research using automobile Blue economic development. They are Cadott, Boyd, Stanley, Thorp, Books, aerial photographs and field work. Withee, Owen, and Curtiss. The group sought a community- connecting theme through which to promote themselves. These He has traveled hundreds of miles through several states and has communities are not suburbs looking for a city. They each offer a come up with additional information about the route and some buffet of little gems like city parks, beautiful centenary churches, changes in maps previously composed by John Ridge. This is quaint restaurants, and American history in addition to particularly useful to John who now has some modern industry. someone who is a tremendous help in The group chose the Yellowstone Trail as its unifying documenting the theme, showing the group’s knowledge of the route of thousands of detailed the Trail along present highway County X, and of its turns and twists as historic importance. -

Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report

City of Madison, Wisconsin Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report By Jennifer L. Lehrke, AIA, NCARB, Rowan Davidson, Associate AIA and Robert Short, Associate AIA Legacy Architecture, Inc. 605 Erie Avenue, Suite 101 Sheboygan, Wisconsin 53081 and Jason Tish Archetype Historic Property Consultants 2714 Lafollette Avenue Madison, Wisconsin 53704 Project Sponsoring Agency City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development 215 Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard Madison, Wisconsin 53703 2017-2020 Acknowledgments The activity that is the subject of this survey report has been financed with local funds from the City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development. The contents and opinions contained in this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the city, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the City of Madison. The authors would like to thank the following persons or organizations for their assistance in completing this project: City of Madison Richard B. Arnesen Satya Rhodes-Conway, Mayor Patrick W. Heck, Alder Heather Stouder, Planning Division Director Joy W. Huntington Bill Fruhling, AICP, Principal Planner Jason N. Ilstrup Heather Bailey, Preservation Planner Eli B. Judge Amy L. Scanlon, Former Preservation Planner Arvina Martin, Alder Oscar Mireles Marsha A. Rummel, Alder (former member) City of Madison Muriel Simms Landmarks Commission Christina Slattery Anna Andrzejewski, Chair May Choua Thao Richard B. Arnesen Sheri Carter, Alder (former member) Elizabeth Banks Sergio Gonzalez (former member) Katie Kaliszewski Ledell Zellers, Alder (former member) Arvina Martin, Alder David W.J. McLean Maurice D. Taylor Others Lon Hill (former member) Tanika Apaloo Stuart Levitan (former member) Andrea Arenas Marsha A. -

Copy of Censusdata

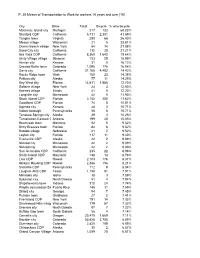

P. 30 Means of Transportation to Work for workers 16 years and over [16] City State Total: Bicycle % who bicycle Mackinac Island city Michigan 217 132 60.83% Stanford CDP California 5,711 2,381 41.69% Tangier town Virginia 250 66 26.40% Mason village Wisconsin 21 5 23.81% Ocean Beach village New York 64 14 21.88% Sand City city California 132 28 21.21% Isla Vista CDP California 8,360 1,642 19.64% Unity Village village Missouri 153 29 18.95% Hunter city Kansas 31 5 16.13% Crested Butte town Colorado 1,096 176 16.06% Davis city California 31,165 4,493 14.42% Rocky Ridge town Utah 160 23 14.38% Pelican city Alaska 77 11 14.29% Key West city Florida 14,611 1,856 12.70% Saltaire village New York 24 3 12.50% Keenes village Illinois 41 5 12.20% Longville city Minnesota 42 5 11.90% Stock Island CDP Florida 2,152 250 11.62% Goodland CDP Florida 74 8 10.81% Agenda city Kansas 28 3 10.71% Volant borough Pennsylvania 56 6 10.71% Tenakee Springs city Alaska 39 4 10.26% Tumacacori-Carmen C Arizona 199 20 10.05% Bearcreek town Montana 52 5 9.62% Briny Breezes town Florida 84 8 9.52% Barada village Nebraska 21 2 9.52% Layton city Florida 117 11 9.40% Evansville CDP Alaska 22 2 9.09% Nimrod city Minnesota 22 2 9.09% Nimrod city Minnesota 22 2 9.09% San Geronimo CDP California 245 22 8.98% Smith Island CDP Maryland 148 13 8.78% Laie CDP Hawaii 2,103 176 8.37% Hickam Housing CDP Hawaii 2,386 196 8.21% Slickville CDP Pennsylvania 112 9 8.04% Laughlin AFB CDP Texas 1,150 91 7.91% Minidoka city Idaho 38 3 7.89% Sykeston city North Dakota 51 4 7.84% Shipshewana town Indiana 310 24 7.74% Playita comunidad (Sa Puerto Rico 145 11 7.59% Dillard city Georgia 94 7 7.45% Putnam town Oklahoma 27 2 7.41% Fire Island CDP New York 191 14 7.33% Shorewood Hills village Wisconsin 779 57 7.32% Grenora city North Dakota 97 7 7.22% Buffalo Gap town South Dakota 56 4 7.14% Corvallis city Oregon 23,475 1,669 7.11% Boulder city Colorado 53,828 3,708 6.89% Gunnison city Colorado 2,825 189 6.69% Chistochina CDP Alaska 30 2 6.67% Grand Canyon Village Arizona 1,059 70 6.61% P. -

An Oral History Project Catalogue

1 A Tribute to the Eastside “Words of Wisdom - Voices of the Past” An Oral History Project Catalogue Two 2 FORWARD Oral History Resource Catalogue (2016 Edition) Eastside Heritage Center has hundreds of oral histories in our permanent collection, containing hours of history from all around East King County. Both Bellevue Historical Society and Marymoor Museum had active oral history programs, and EHC has continued that trend, adding new interviews to the collection. Between 1996 and 2003, Eastside Heritage Center (formerly Bellevue Historical Society) was engaged in an oral history project entitled “Words of Wisdom – Voices of the Past.” As a part of that project, Eastside Heritage Center produced the first Oral History Resource Catalogue. The Catalogue is a reference guide for researchers and staff. It provides a brief introduction to each of the interviews collected during “Words of Wisdom.” The entries contain basic information about the interview date, length, recording format and participants, as well as a brief biography of the narrator, and a list of the topics discussed. Our second catalogue is a continuation of this project, and now includes some interviews collected prior to 1996. The oral history collection at the Eastside Heritage Center is constantly expanding, and the Catalogue will grow as more interviews are collected and as older interviews are transcribed. Special thanks to our narrators, interviewers, transcribers and all those who contributed their memories of the Eastside. We are indebted to 4Culture for funding this project. Eastside Heritage Center Oral History Committee 3 Table of Contents Forward and Acknowledgments pg. 2 Narrators Richard Bennett, with Helen Bennett Johnson pg. -

The Artists' View of Seattle

WHERE DOES SEATTLE’S CREATIVE COMMUNITY GO FOR INSPIRATION? Allow us to introduce some of our city’s resident artists, who share with you, in their own words, some of their favorite places and why they choose to make Seattle their home. Known as one of the nation’s cultural centers, Seattle has more arts-related businesses and organizations per capita than any other metropolitan area in the United States, according to a recent study by Americans for the Arts. Our city pulses with the creative energies of thousands of artists who call this their home. In this guide, twenty-four painters, sculptors, writers, poets, dancers, photographers, glass artists, musicians, filmmakers, actors and more tell you about their favorite places and experiences. James Turrell’s Light Reign, Henry Art Gallery ©Lara Swimmer 2 3 BYRON AU YONG Composer WOULD YOU SHARE SOME SPECIAL CHILDHOOD MEMORIES ABOUT WHAT BROUGHT YOU TO SEATTLE? GROWING UP IN SEATTLE? I moved into my particular building because it’s across the street from Uptown I performed in musical theater as a kid at a venue in the Seattle Center. I was Espresso. One of the real draws of Seattle for me was the quality of the coffee, I nine years old, and I got paid! I did all kinds of shows, and I also performed with must say. the Civic Light Opera. I was also in the Northwest Boy Choir and we sang this Northwest Medley, and there was a song to Ivar’s restaurant in it. When I was HOW DOES BEING A NON-DRIVER IMPACT YOUR VIEW OF THE CITY? growing up, Ivar’s had spokespeople who were dressed up in clam costumes with My favorite part about walking is that you come across things that you would pass black leggings. -

This City of Ours

THIS CITY OF OURS By J. WILLIS SAYRE For the illustrations used in this book the author expresses grateful acknowledgment to Mrs. Vivian M. Carkeek, Charles A. Thorndike and R. M. Kinnear. Copyright, 1936 by J. W. SAYRE rot &?+ *$$&&*? *• I^JJMJWW' 1 - *- \£*- ; * M: . * *>. f* j*^* */ ^ *** - • CHIEF SEATTLE Leader of his people both in peace and war, always a friend to the whites; as an orator, the Daniel Webster of his race. Note this excerpt, seldom surpassed in beauty of thought and diction, from his address to Governor Stevens: Why should I mourn at the untimely fate of my people? Tribe follows tribe, and nation follows nation, like the waves of the sea. It is the order of nature and regret is useless. Your time of decay may be distant — but it will surely come, for even the White Man whose God walked and talked with him as friend with friend cannot be exempt from the common destiny. We may be brothers after all. Let the White Man be just and deal kindly with my people, for the dead are not powerless. Dead — I say? There is no death. Only a change of worlds. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE 1. BELIEVE IT OR NOT! 1 2. THE ROMANCE OF THE WATERFRONT . 5 3. HOW OUR RAILROADS GREW 11 4. FROM HORSE CARS TO MOTOR BUSES . 16 5. HOW SEATTLE USED TO SEE—AND KEEP WARM 21 6. INDOOR ENTERTAINMENTS 26 7. PLAYING FOOTBALL IN PIONEER PLACE . 29 8. STRANGE "IFS" IN SEATTLE'S HISTORY . 34 9. HISTORICAL POINTS IN FIRST AVENUE . 41 10. -

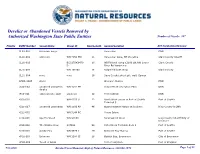

Report Document

Derelict or Abandoned Vessels Removed by Authorized Washington State Public Entities Number of Vessels: 867 Priority DVRP Number Vessel Name Vessel ID Boat Length General Location APE Conducting Removal CL03-001 Unknown barge Vancouver DNR CL10-002 unknown WN 7354 MD 31 Vancouver Lake, NE shoreline Clark County Sheriff CL10-003 BCC17543M79 16 WDFW boat ramp 12100 blk NW Lower Clark County D River Rd Vancouver CL10-004 WN 106 GA 16 Ridgefield boat ramp Clark County CL11-004 none none 16 Davy Crocket sheet pile wall, Camus GH03-002B Arctic Westport Marina DNR IS12-002 unnamed Livingston WN 4154 MF Anacortes at Deception Pass DNR dinghy JF10-011 unknown blue skiff unknown 12 Port Hadlock DNR KI08-010 WN 6250 V 22 North West corner of Port of Seattle Port of Seattle Terminal 5 KI10-017 unnamed catamaran WN 1983 NP 46 Quartermaster Harbor at Dockton King County & DNR KI11-005 WN 5148 RC Maury Island KI12-006 Sport'n Wood WN 9566X Sammamish River King County Sheriff/City of Kenmore KI15-016 The Wazzu Crew 297584 54 Fishermens Terminal dock 8 Port of Seattle KI15-020 Adulis-Zula WN 9979 J 29 Shilshole Bay Marina Port of Seattle KP03-004 Unknown WN 1584 JE 26 Ostrich Bay, Bremerton City of Bremerton KP03-008 Touch of Glass Port of Kingston Port of Kingston 7/31/2019 Derelict Vessel Removal, Dept of Natural Resouces, 360-902-1574 Page 1 of 42 Priority DVRP Number Vessel Name Vessel ID Boat Length General Location APE Conducting Removal KP03-011A Petunia Eagle Harbor City of Bainbridge Island KP03-011B Unknown2 Eagle Harbor City of Bainbridge Island -

Geographic Classification, 2003. 577 Pp. Pdf Icon[PDF – 7.1

Instruction Manual Part 8 Vital Records, Geographic Classification, 2003 Vital Statistics Data Preparation U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics Hyattsville, Maryland October, 2002 VITAL RECORDS GEOGRAPHIC CLASSIFICATION, 2003 This manual contains geographic codes used by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) in processing information from birth, death, and fetal death records. Included are (1) incorporated places identified by the U.S. Bureau of the Census in the 2000 Census of Population and Housing; (2) census designated places, formerly called unincorporated places, identified by the U.S. Bureau of the Census; (3) certain towns and townships; and (4) military installations identified by the Department of Defense and the U.S. Bureau of the Census. The geographic place of occurrence of the vital event is coded to the state and county or county equivalent level; the geographic place of residence is coded to at least the county level. Incorporated places of residence of 10,000 or more population and certain towns or townships defined as urban under special rules also have separate identifying codes. Specific geographic areas are represented by five-digit codes. The first two digits (1-54) identify the state, District of Columbia, or U.S. Possession. The last three digits refer to the county (701-999) or specified urban place (001-699). Information in this manual is presented in two sections for each state. Section I is to be used for classifying occurrence and residence when the reporting of the geographic location is complete. -

The Washington Way

THE WASHINGTON WAY WASHINGTON HUSKIES 2007 FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE THE WASHINGTON WAY Husky Football A to Z Here’s a look at some of the more interesting AMERICAN IDOL: The highest-rated television aspects of the University of Washington, its athletic show in the nation, “American Idol” featured former history and the Huskies’ proud football tradition. Husky offensive guard Matt Rogers during the 2004 season. The Fox network program, which was in GENERAL INFO. AIR HUSKY: A familiar sight around Husky Stadium its third season, featured a talent search for the are the low-flying float planes that use Lake Wash- nation’s next pop superstar. Rogers was one of ington and Lake Union as their staging areas. One more than 40,000 contestants to audition around company, Kenmore Air Harbor of Kenmore, Wash., the country. He wowed the panel of celebrity judges offers UW fans a chance to fly in the one-of-a-kind (including pop star Paula Abdul) and the voting Husky Air Force. One plane in its fleet, a 10-pas- public with his singing and stage presence. Through senger deHavilland Turbine Otter, has been detailed a series of elimination stages and telephonic voting OUTLOOK with the Husky color scheme and logos. by the public, Rogers advanced to the round of live televised performances and placed 11th overall. The ALMA MATER: Here are the lyrics to Washington’s former offensive guard has toured with the other alma mater: finalists, and recorded a rendition of “Dock of the To her we sing who keeps the ward Bay.” Rogers’ single was featured on the “American O’er all her sons from sea to sea; Idol Season 3: Greatest Soul Classics” album Our Alma Mater, Washington, released in 2004. -

Arrow #15 V14.Cdr

Number 15 Official Publication of The Yellowstone Trail Association “A Good Road from Plymouth Rock to Puget Sound” The Arrow is back! Trail-O-Grams A note from the Ridges: After a three-year hiatus, the Yellowstone ¦Jim Marx of Michigan is Trail Association is ready for members again and is ready to planning to bicycle the Trail from produce the Arrow! We never really went away. The non-profit Seattle to Plymouth Rock this 501(c)3 status has been retained and we and many YTA members summer! See his blog. Visit have been very busy, so busy that we stopped soliciting http://jimarx.tumblr.com/ memberships and sending Arrows for a simple lack of time. The purpose of the organization is still to promote, educate, research, Also, we will follow him on our and preserve the Yellowstone Trail. But since the first of the year Facebook page: we have Mark Mowbray, volunteer Executive Director, to direct www.facebook.com/YellowstoneTrail Better than a membership matters and the operational aspects of the YTA. That Read his blog and learn how to contact Model T? allows us to continue our research and writing about the Trail. him when he comes through your town. That is the good news for all of us. The bad news (well not so very Arrange to meet him and get some bad) is that the newsletter, the Arrow, can no longer come at you in publicity for the YT in your town! printed form via the postal system. The printing, mailing costs, and ¦Hudson, Wisconsin’s Yellowstone Trail weekend, May 14- time requirements are prohibitive .