Balancing the Creative Business Model Essays on Business Models of Creative Organizations Within and Between Institutional Fields

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bible for Boats 40 Years Measuring Yacht Hulls

Outlook DelftMAGAZINE OF DELFT UniVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY 2013 • 1 Bible for boats 40 years measuring yacht hulls Digital Dora Black box in the operating room Paul Rullmann ‘I value students’ contribution’ Leading ladies Finding talented women 1 Contents Delft in Brief no. 1 3 Delft in brief 13 Column Remco de Boer Efficient dredging 13 Work in progress The dredgers seem to be fighting a losing battle in the river Waal; the water- way is silting up more quickly as a result of the floodplains being lowered 20 New Applied Sciences building and the summer dikes moved. Reason enough for student Tim van der Lugt 2013 (CEG) to spend this winter trying out something new, together with the 22 Hora est, propositions, cartoon and soundbites captain of dredger M.S. Dintel. Rather than levelling the sandbanks with a vertical plate, the dredgers take a ‘bite’ of sand, which they then move under 23 View: Maarten van Ham on deprived neighbourhoods water and deposit elsewhere. This reduces friction tremendously. The tech- nique has not yet been fully developed. On one occasion, the stern of the 23 Since you asked: Money for Groningen ship completely disappeared under water when the flap valve of the plough failed to open quickly enough. Bible for yacht builders 24 In person Photo: Tomas van Dijk van Tomas Photo: delta.tudelft.nl/26160 6 25 The firm 25 Life after Delft Get out of here 26 Alumni news Evacuations could be accomplished more effectively and efficiently by equipping people in the affected area with simple means of naviga- tion and communication, so argues PhD candidate Lucy T. -

Miss Groningen En Hanzemag Wensen Jullie Een Geweldige Zomer! HG-Voorzitter Pijlman Content Met Prestatie-Afspraken in De Dop

uitblinkers of uitslovers? 17e jaargang 20 juni 2012 redactioneel onafhankelijk magazine van de Hanzehogeschool Groningen | e-mail: [email protected] | Foto: Pepijn van den Broeke | Model: Chanel Feikens 11 Miss Groningen enHanzeMag wensen jullie een geweldige zomer! geweldige een jullie wensen HG-voorzitter Pijlman content met prestatie-afspraken in de dop ‘Het is goed om de boel af en toe op te schudden’ Eind juli oordeelt de door het ministerie van Onderwijs ingestelde commissie Hoger Onderwijs en Onderzoek over de inhoud van het prestatiecontract dat de HG in september wil sluiten met de staatssecretaris. In het contract staan afspraken over de door HG- voorzitter Henk Pijlman beoogde vermindering van de overhead. Voor september 2016 sneuvelen er tijden de boel eens op te schudden. Wat tot december de tijd om de plannen 240 banen in de overhead. Nogal een doen we? Doen we dat efficiënt? En wat uit te werken en te bespreken met de De prestatie-afspraken ingreep. verandert er in de omgeving? Neem de medewerkers.’ In de periode tussen september 2012 ‘De verhouding tussen onderwijs- en studentenadministratie, daar werken en september 2016 zal de Hanzehoge- ondersteunend personeel is al langer uit honderd mensen. We verwachten dat De overheadreductie staat in de zoge- school (HG) een aantal veranderingen evenwicht. Vorig jaar hadden we voor we door verdergaande automatisering heten prestatie-afspraken. Als de HG doorvoeren die ertoe leiden dat het 1550 fte (fulltime equivalent, volledige met minder mensen toe kunnen. Maar die niet nakomt, kort het ministerie ministerie van Onderwijs, de rijksbij- banen van 38 uur per week, red.) aan die mensen kunnen weer ander nuttig op de rijksbijdrage. -

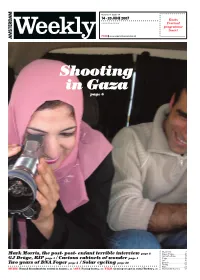

Print Amsweekly.Ver4

Volume 4, Issue 24 14 - 20 JUNE 2007 Roots www.bokitomotvrij.nl Festival programme insert FREE www.amsterdamweekly.nl Shooting in Gaza page 6 Short List . .9 Mark Morris, the post- post- enfant terrible interview page 8 Music/Clubs . .13 Gay & Lesbian . .17 GJ Dröge, RIP page 4 / Curious cabinets of wonder page 4 Stage . .17 Art . .18 page 5 page 20 Events . .22 Two years of DNA Foyer / Solar cycling Dining . .23 Film . .24 MUSIC: Nomad Soundsystem rooted in fusion p. 11 / ART: Facing faces p. 21 / FILM: Coming of age in rural Turkey p. 25 Classifieds/Comics . .29 14-20 June 2007 Amsterdam Weekly 3 AT TACHMENT S In this issue and... Philosopher Richard Rorty, who died last Friday, famously said: ‘[Solidarity] is created by increasing our sensitivity to the particular details of the pain and humiliation of other, unfamiliar sorts of people. Such increased sensitivity makes it more difficult to marginalise people different from ourselves by thinking, “They do not feel as WE would,” or “There must always be suf- fering, so why not let THEM suffer?”’ Some seek solidarity by making films in war zones. Others take photographs of people making goofy faces in war zones. Meanwhile, the military com- plex reveals its two sides. First, there’s cuddly teddy bear-faced Battlefield Extraction Assist Robot (BEAR) to res- cue wounded troops. Second, the Pentagon confirmed this week it seri- ously thought about developing a ‘gay bomb’ that would shower hormones on troops and make them—quote—’irre- sistibly attractive to one another’. And to think the Chinese regard ‘may you live in interesting times’ as a curse. -

Paranoia on the Nile

The politics of flood insecurity Framing contested river management projects Jeroen F. Warner Promotoren: Prof. Dr. Ir. D.J.M. Hilhorst Hoogleraar Humanitaire Hulp en Wederopbouw Prof. Dr. Ir. C. Leeuwis Hoogleraar Communicatie en Innovatie Studies Promotiecommissie Prof. Dr. J.A. Allan King‟s College, London Prof. Dr. H.J.M. Goverde Wageningen Universiteit / Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen Prof. Dr. Mr. B.J.M. van der Meulen Wageningen Universiteit Prof. Dr. J.H. de Wilde Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de onderzoeksschool CERES – Research School for Resource Studies for Development. The politics of flood insecurity Framing contested river management projects Jeroen F. Warner Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, prof. dr. M.J. Kropff, in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 18 maart 2008 des namiddags om 16.00 uur in de Aula. Jeroen F. Warner The politics of flood insecurity Framing contested river management projects ISBN 978-80-8504-897-8 Table of Contents List of Figures, Tables and Boxes List of Abbreviations 1. Introduction: The politics of floods and fear 1 2. Midnight at Noon? The dispute over Toshka, Egypt 31 3. Resisting the Turkish pax aquarum? The Ilısu Dam dispute as a multi-level struggle 57 4. Turkey and Egypt – tales of war, peace and hegemony 83 5. Death of the mega-projects? The controversy over Flood Action Plan 20, Bangladesh 111 6. The Maaswerken project: Fixing a hole? 145 7. Public Participation in emergency flood storage in the Ooij polder – a bridge too far? 173 8. -

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI Via AP Balazs Mohai

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI via AP Balazs Mohai Sziget Festival March 26-April 2 Horizon Festival Arinsal, Andorra Web www.horizonfestival.net Artists Floating Points, Motor City Drum Ensemble, Ben UFO, Oneman, Kink, Mala, AJ Tracey, Midland, Craig Charles, Romare, Mumdance, Yussef Kamaal, OM Unit, Riot Jazz, Icicle, Jasper James, Josey Rebelle, Dan Shake, Avalon Emerson, Rockwell, Channel One, Hybrid Minds, Jam Baxter, Technimatic, Cooly G, Courtesy, Eva Lazarus, Marc Pinol, DJ Fra, Guim Lebowski, Scott Garcia, OR:LA, EL-B, Moony, Wayward, Nick Nikolov, Jamie Rodigan, Bahia Haze, Emerald, Sammy B-Side, Etch, Visionobi, Kristy Harper, Joe Raygun, Itoa, Paul Roca, Sekev, Egres, Ghostchant, Boyson, Hampton, Jess Farley, G-Ha, Pixel82, Night Swimmers, Forbes, Charline, Scar Duggy, Mold Me With Joy, Eric Small, Christer Anderson, Carina Helen, Exswitch, Seamus, Bulu, Ikarus, Rodri Pan, Frnch, DB, Bigman Japan, Crawford, Dephex, 1Thirty, Denzel, Sticky Bandit, Kinno, Tenbagg, My Mate From College, Mr Miyagi, SLB Solden, Austria June 9-July 10 DJ Snare, Ambiont, DLR, Doc Scott, Bailey, Doree, Shifty, Dorian, Skore, March 27-April 2 Web www.electric-mountain-festival.com Jazz Fest Vienna Dossa & Locuzzed, Eksman, Emperor, Artists Nervo, Quintino, Michael Feiner, Full Metal Mountain EMX, Elize, Ernestor, Wastenoize, Etherwood, Askery, Rudy & Shany, AfroJack, Bassjackers, Vienna, Austria Hemagor, Austria F4TR4XX, Rapture,Fava, Fred V & Grafix, Ostblockschlampen, Rafitez Web www.jazzfest.wien Frederic Robinson, -

Onderzoeksverslag Is Authenticiteit 4 Real 11112016LVDM Kopie.Pages

Is authenticiteit 4 real? Wat is authenticiteit in de Nederlandse populaire muziek eigenlijk? En is het te leren? HET PROBLEMATISEREN VAN AUTHENTICITEIT ALS SLEUTEL TOT HET ONTWIKKELEN VAN EEN EIGEN STIJL “I know I’m good, but I’m also a poser. That’s artistic balance! In the second half of the twentieth century ‘authenticity’ would be what you made of it. A hall of mirrors.” - Bruce Springsteen, uit: Born to Run. !1 popopleiding volgen worden geacht om zelf, buiten het curriculum een vorm van authenticiteit te ontwikkelen. Authenticiteit lijkt door Voorwoord docenten, publiek en gatekeepers te worden gezien als iets wat je “I cook! I clean! I do laundry! I clean my own dishes! I still do my own hebt of niet. Dit blijkt bijvoorbeeld uit de doorlopende kritiek op pop- dishes at my house, because I’m a fucking real person! As if someone en kunstvakopleidingen, die ook ik als docent te horen krijg: ‘echte’ else is supposed to be doin’ it, right?” - Action Bronson, uit: Munchies. artiesten zouden niet van zo’n opleiding komen. Kunnen jonge pop- artiesten op de opleiding niet juist begeleid worden in het ontwikke- Met enige regelmaat valt in recensies van albums of optredens te le- len van authenticiteit, in plaats van aan te nemen dat dit een kwaliteit zen dat een artiest volstrekt authentiek, origineel of eigenzinnig is. is die a priori aanwezig is? Over het algemeen is dit een compliment of aanbeveling. ‘(…) when something is described as “authentic”, what is invariably meant is that Dit onderzoek is een poging om de betekenis van authenticiteit binnen it is a Good Thing.’ (Potter, 2010, p. -

EUROSONIC IS COMING HOME - HOSTING NATION HOLLAND IS THIS YEAR’S FOCUS COUNTRY by Robbert Tilli

AT THE 25 TH ANNIVERSARY OF EUROSONIC NOORDERSLAG: - EUROSONIC IS COMING HOME - HOSTING NATION HOLLAND IS THIS YEAR’S FOCUS COUNTRY By Robbert Tilli * EUROSONIC NOORDERSLAG CONFERENCE JANUARY 12, 13, 14, 15, 2011 This year marks the 25th anniversary of the Eurosonic Noorderslag music conference and showcase festival. And after years with interesting focuses on countries such as Italy, Belgium and Norway, finally Eurosonic Noorderslag is coming home. Hosting nation Holland is this year’s focus country. Birthday boy is pushing the boat out with a presentation of a range of great Dutch bands. Holland’s musical history in a nutshell The topic of the ‘possible existence of a history of Dutch music’ sometimes generates interesting discussions at the bar at the international music conferences. There’s always a group of registrants that starts singing Golden Earring’s 1972 global monster smash Radar Love straightaway, and there’s that group of hipsters who deliberately start staring ignorantly. ‘Dutch music? Yeah, yeah,’ they say. What’s that? ‘Name a few bands then?’ In recent years we’ve seen a lot of true aficionados of Dutch pop, rock and dance, but also we’ve met the sceptics, who simply denied the existence of such a thing as Dutch music. Rembrandt, Vermeer, Van Gogh, okay, they acknowledge the Dutch masters of painting. But pop, rock, dance? ‘No, never heard of.’ It’s time to prove them wrong. Holland is focus country, and you’ll know it. To be fair, the awareness of Dutch pop, rock and dance history could do with a little boost. -

Country Y R T N U O C Country

COUNTRY COUNTRY .................................1 BEAT, 60s/70s.............................50 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. ........................14 SURF ........................................60 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER ..................16 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY .......................62 WESTERN .....................................20 BRITISH R&R ...................................67 WESTERN SWING ...............................21 AUSTRALIAN R&R ...............................68 TRUCKS & TRAINS ..............................22 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT ........................68 C&W SOUNDTRACKS............................22 POP .......................................69 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS ......................23 LATIN ........................................82 COUNTRY CANADA .............................23 JAZZ.........................................83 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND ...............24 SOUNDTRACKS ................................84 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE .................25 SWING.......................................85 BLUEGRASS ...................................25 ........................86 NEWGRASS ...................................27 DEUTSCHE OLDIES KLEINKUNST / KABARETT .........................88 INSTRUMENTAL ................................28 OLDTIME .....................................28 BOOKS ....................................89 HAWAII ......................................29 DISCOGR./REFERENCES STYLES ....................94 CAJUN/ZYDECO/TEX MEX ........................30 PRICE GUIDES .................................94 -

Poppodia 2004

in-sight poppodia 2004 www.vnpf.nl 2 1 Inhoud 2 14 Wat doet de VNPF? Financiën 4 Hoeveel geld gaat er om in VNPF podia de sector? Hoeveel zijn er en waar zitten ze? 6 18 Nieuwbouw en verbouw Werkgelegenheid Hoeveel (betaalde) banen zijn er? 8 Activiteiten 20 Wat gebeurt er op de podia en hoeveel bezoek komt er op af? Verwachtingen Wat verwachten de podia van 2005? 10 Regionale spreiding 22 12 Ledenlijst podia Artiesten Hoe vaak treden zij op en waar 25 komen ze vandaan? Meer informatie? VERANTWOORDING 4 Deze publicatie geeft een overzicht van gegevens van 75 poppodia die actief waren in 2004 en in 2005 lid zijn van de VNPF. Van 53 van deze podia zijn de bedrijfsgegevens verzameld (een respons van 71%). Voor deze publicatie zijn gegevens van de non-respons bijgeschat. De VNPF verzamelt de bedrijfsgegevens systematisch sinds 2002. Omdat per jaar de respons anders is, kunnen de bijgeschatte totalen om die reden alleen al Wat doet de VNPF? verschillen. Daar waar in deze publicatie vergelijkingen met voorgaande jaren worden gemaakt, wordt zoveel mogelijk met dit effect rekening gehouden. De Vereniging Nederlandse Poppodia en Omdat de Heineken Music Hall als grootste podium een significant effect heeft –Festivals is sinds 1993 de branchevereni- op de cijfers, maar sinds 2003 geen lid meer is van de VNPF, zijn de gegevens uit het jaar 2002 opnieuw bijgeschat, met weglating van de Heineken Music ging van de poppodia en popfestivals in Hall. Vergelijkingen met de gegevens in de publicatie VNP In-sight 2002 zijn Nederland. daarom niet één op één te maken. -

Dutch-Composers-Now-2018-Web

Dutch Composers NOW Reimagining the concert century world. International research practice among outstanding artists and institu- tions points to a way of working that can Dutch Composers NOW is a collabora- ESSAY BY MASA SPAAN be analyzed as Baricco’s horizontal way of tion between Nieuw Geneco (Dutch CURATOR AND PROGRAM DEVELOPER IN signification. In fact, they are already un- Composers Association), Donemus CLASSICAL AND NEW MUSIC derpinning his ideas. Without seeming to Publishing, Deuss Music/Albersen, The traditions and conventions associated have completely discarded old-fashioned GLERUM NICHON VMN Dutch Music Publishers Associa- with classical music came into being in the profundity, their programming exposes tion and Buma Cultuur to promote the nineteenth century. Drawing on the pow- ideas, which give the material, that is in- sion. For Fischer, daughter of the conduc- creation of new music. Together we erful and related principles of formalism trinsically musical, a relevant connection tor Ivan Fischer, the classics were always represent the composers living and and musical autonomy, such principles still with the spirit of our times. going to be at the root of her artistry. She working in the Netherlands; creators of hold sway over much of today’s classical always knew what she wanted to sing, but both complex and accessible, conven- concert practice. As twenty-first century Taken together, it points to a comprehen- all of the previously carved-out paths tionally as well as unconventionally human beings, this ritual seems to have sive strategy, from idea to audience, in were just not for her, she felt. Making her composed music. -

Släpstick Teacher Resource

Curriculum Links Drama Music Contents Cast and Creatives About the Show Biographies Production and Techniques Further Resources Provocations and Activities Download SchoolFest 101 here. Your guide to make the most of the festival experience. Image: Jaap Reedijik Släpstick 2020 TEACHERS RESOURCE CAST AND CREATIVES Website: www.slapstick.nl Concept, compositions & arrangements: Släpstick, Ro Krauss, Willem van Baarsen, Rogier Bosman, Sanne van Delft and Jon Bittman Direction: Stanley Burleson Direction advice: Karel de Rooij Set design and creation: Jacco van den Dool, Siem van Leeuwen, Ellen Windhorst Costumes: Jan Aarntzen Lighting design: Jacco van den Dool, Wouter Moscou Sound design: Joep van der Velden SLÄPSTICK was founded in 1997 (originally under the name 'Wereldband'). Ro Krauss, Willem van Baarsen, Rogier Bosman and Sanne van Delft met at music school, and decided to start a band. The core of the Släpstick was born and is still intact to this day. Jon Bittman joined the group in 2012. Budding friendships combined with the communal quest for new and strange musical instruments and a shared need for laughter led to fresh and interesting ideas. Although they happily plundered music from the many genres, they began writing more and more of their own compositions. From 1997 onwards Släpstick performed at various music venues and festivals, while at the same time developing ludicrous theatrical scenes to accompany their tunes. In 2005 they made the inevitable leap from being a band to the theatre stage. The guys deftly switched between trumpets, violins and musical saws the way a juggler might play catch with a bowling ball, a flaming torch, and, well.. -

No Risk Disc: Palio Super- Speed Donkey

Het blad van/voor muziekliefhebbers 7 december 2012 | nr. 293 No Risk Disc: Palio SuPer- SPeed donkey www.platomania.nl • www.sounds-venlo.nl • www.kroese-online.nl • www.velvetmusic.nl • www.waterput.nl • www.de-drvkkery.nl adv_uni_plato_michael kiwanuka_fc_©OCHEDA 20-11-12 11:22 Pagina 1 mania 293 DELUXE DUTCH EDITION N RISK DISCNIET GOED GELD TERUG “ECHT HEMELS MOOI” ★★★★ [PAROOL] “GROOTS! ALLES VIBREERT EN TRILT” ★★★★ [NRC] “WERKELIJK GEWELDIG!” [3FM] Palio SuPerSPeed donkey Wateramp (Topnotch/Universal) Amsterdams, piepjong, talentvol, OPGENOMEN MET HET hard, ruig en aanstekelijk; dat is Palio Superspeed METROPOLE ORKEST Donkey in een notendop. De band werd in 2011 IN CARRE AMSTERDAM opgericht, waarbij ze niet veel later een uitnodiging voor een optreden op Into The Great Wide Open in de brievenbus vonden. Op het pittoreske Vlieland kwam het viertal uitstekend voor de dag en nadat de nodige lovende kritieken in sneltreinvaart over Nederland werden verspreid, ging het qua media- aandacht net zo rap als de riffs van gitarist Willem Smit. Een kleine kink in de kabel bleek de ziekte van Pfeiffer die zanger Sam Vermeulen, gekenmerkt door een nonchalante spuuglok à la James Dean, als het jonge broertje van Arctic Monkeys en enkele maanden buitenspel zette. De tieners, met met Pixies en Pavement als grote voorbeelden, VERKRIJGBAAR ALS: een gemiddelde leeftijd van vijftien (!) jaar, stonden wordt met de ep Wateramp een kwartier aan 2CD | DOWNLOAD derhalve in het voorprogramma van Dazzled Kid, onmiskenbare kwaliteit afgeleverd. Met een Chef’Special en Kensington, zagen verschillende platencontract bij Top Notch op zak en optredens tunes gebruikt worden in commercials, speelden hun op ondermeer Noorderslag en Where The Wild hit Mr.