Duboisia Pituri: a Natural History∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

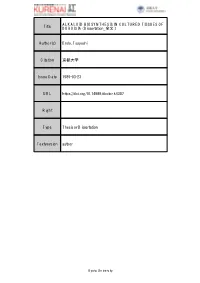

Title ALKALOID BIOSYNTHESIS in CULTURED TISSUES OF

ALKALOID BIOSYNTHESIS IN CULTURED TISSUES OF Title DUBOISIA( Dissertation_全文 ) Author(s) Endo, Tsuyoshi Citation 京都大学 Issue Date 1989-03-23 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/doctor.k4307 Right Type Thesis or Dissertation Textversion author Kyoto University ALKALOID BIOSYNTHESIS IN C;ULTURED TISSUES OF DUBOISIA . , . ; . , " 1. :'. '. o , " ::,,~./ ~ ~';-~::::> ,/ . , , .~ - '.'~ . / -.-.........."~l . ~·_l:""· .... : .. { ." , :: I i i , (, ' ALKALOID BIOSYNTHESIS IN CULTURED TISSUES OF DUBOISIA TSUYOSHIENDO 1989 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ----------1 CHAPTER I ALKALOID PRODUCTION IN CULTURED DUBOISIA TISSUES. INTRODUCTION ----------6 SECTION 1 Alkaloid Production and Plant Regeneration from ~ leichhardtii Calluses. ----------8 SECTION 2 Alkaloid Production in Cultured Roots of Three Species of Duboisia. ---------16 SECTION 3 Non-enzymatic Synthesis of Hygrine from Acetoacetic Acid and from Acetonedicar- boxylic Acid. ---------25 CHAPTER II SOMATIC HYBRIDIZATION OF DUBOISIA AND NICOTIANA. INTRODUCTION ---------35 SECTION 1 Establishment of an Intergeneric Hybrid Cell Line of ~ hopwoodii and ~ tabacum. ---------38 SECTION 2 Genetic Diversity Originating from a Single Somatic Hybrid Cell. ---------47 SECTION 3 Alkaloid Biosynthesis in Somatic Hybrids, D. leichhardtii + ~ tabacum ---------59 CONCLUSIONS ---------76 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ---------79 REFERENCES ---------80 PUBLICATIONS ---------90 ABBREVIATIONS BA 6-benzyladenine OAPI 4',6-diamino-2-phenylindoledihydrochloride EDTA ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid GC-MS gas chromatography - mass spectrometry -

Cravens Peak Scientific Study Report

Geography Monograph Series No. 13 Cravens Peak Scientific Study Report The Royal Geographical Society of Queensland Inc. Brisbane, 2009 The Royal Geographical Society of Queensland Inc. is a non-profit organization that promotes the study of Geography within educational, scientific, professional, commercial and broader general communities. Since its establishment in 1885, the Society has taken the lead in geo- graphical education, exploration and research in Queensland. Published by: The Royal Geographical Society of Queensland Inc. 237 Milton Road, Milton QLD 4064, Australia Phone: (07) 3368 2066; Fax: (07) 33671011 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rgsq.org.au ISBN 978 0 949286 16 8 ISSN 1037 7158 © 2009 Desktop Publishing: Kevin Long, Page People Pty Ltd (www.pagepeople.com.au) Printing: Snap Printing Milton (www.milton.snapprinting.com.au) Cover: Pemberton Design (www.pembertondesign.com.au) Cover photo: Cravens Peak. Photographer: Nick Rains 2007 State map and Topographic Map provided by: Richard MacNeill, Spatial Information Coordinator, Bush Heritage Australia (www.bushheritage.org.au) Other Titles in the Geography Monograph Series: No 1. Technology Education and Geography in Australia Higher Education No 2. Geography in Society: a Case for Geography in Australian Society No 3. Cape York Peninsula Scientific Study Report No 4. Musselbrook Reserve Scientific Study Report No 5. A Continent for a Nation; and, Dividing Societies No 6. Herald Cays Scientific Study Report No 7. Braving the Bull of Heaven; and, Societal Benefits from Seasonal Climate Forecasting No 8. Antarctica: a Conducted Tour from Ancient to Modern; and, Undara: the Longest Known Young Lava Flow No 9. White Mountains Scientific Study Report No 10. -

Duboisia Myoporoides R.Br. Family: Solanaceae Brown, R

Australian Tropical Rainforest Plants - Online edition Duboisia myoporoides R.Br. Family: Solanaceae Brown, R. (1810) Prodromus Florae Novae Hollandiae : 448. Type: New South Wales, Port Jackson, R. Brown, syn: BM, K, MEL, NSW, P. (Fide Purdie et al. 1982.). Common name: Soft Corkwood; Mgmeo; Poison Corkwood; Poisonous Corkwood; Corkwood Tree; Eye-opening Tree; Eye-plant; Duboisia; Yellow Basswood; Elm; Corkwood Stem Seldom exceeds 30 cm dbh. Bark pale brown, thick and corky, blaze usually darkening to greenish- brown on exposure. Leaves Leaf blades about 4-12 x 0.8-2.5 cm, soft and fleshy, indistinctly veined. Midrib raised on the upper surface. Flowers. © G. Sankowsky Flowers Small bell-shaped flowers present during most months of the year. Calyx about 1 mm long, lobes short, less than 0.5 mm long. Corolla induplicate-valvate in the bud. Induplicate sections of the corolla and inner surfaces of the corolla lobes clothed in somewhat matted, stellate hairs. Corolla tube about 4 mm long, lobes about 2 mm long. Fruit Fruits globular, about 6-8 mm diam. Seed and embryo curved like a banana or sausage. Seed +/- reniform, about 3-3.5 x 1 mm. Testa reticulate. Habit, leaves and flowers. © Seedlings CSIRO Cotyledons narrowly elliptic to almost linear, about 5-8 mm long. First pair of true leaves obovate, margins entire. At the tenth leaf stage: leaf blade +/- spathulate, apex rounded, base attenuate; midrib raised in a channel on the upper surface; petiole with a ridge down the middle. Seed germination time 31 to 264 days. Distribution and Ecology Occurs in CYP, NEQ, CEQ and southwards as far as south-eastern New South Wales. -

Report to Office of Water Science, Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation, Brisbane

Lake Eyre Basin Springs Assessment Project Hydrogeology, cultural history and biological values of springs in the Barcaldine, Springvale and Flinders River supergroups, Galilee Basin and Tertiary springs of western Queensland 2016 Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation Prepared by R.J. Fensham, J.L. Silcock, B. Laffineur, H.J. MacDermott Queensland Herbarium Science Delivery Division Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation PO Box 5078 Brisbane QLD 4001 © The Commonwealth of Australia 2016 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence Under this licence you are free, without having to seek permission from DSITI or the Commonwealth, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the source of the publication. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5725 Citation Fensham, R.J., Silcock, J.L., Laffineur, B., MacDermott, H.J. -

Appendix Color Plates of Solanales Species

Appendix Color Plates of Solanales Species The first half of the color plates (Plates 1–8) shows a selection of phytochemically prominent solanaceous species, the second half (Plates 9–16) a selection of convol- vulaceous counterparts. The scientific name of the species in bold (for authorities see text and tables) may be followed (in brackets) by a frequently used though invalid synonym and/or a common name if existent. The next information refers to the habitus, origin/natural distribution, and – if applicable – cultivation. If more than one photograph is shown for a certain species there will be explanations for each of them. Finally, section numbers of the phytochemical Chapters 3–8 are given, where the respective species are discussed. The individually combined occurrence of sec- ondary metabolites from different structural classes characterizes every species. However, it has to be remembered that a small number of citations does not neces- sarily indicate a poorer secondary metabolism in a respective species compared with others; this may just be due to less studies being carried out. Solanaceae Plate 1a Anthocercis littorea (yellow tailflower): erect or rarely sprawling shrub (to 3 m); W- and SW-Australia; Sects. 3.1 / 3.4 Plate 1b, c Atropa belladonna (deadly nightshade): erect herbaceous perennial plant (to 1.5 m); Europe to central Asia (naturalized: N-USA; cultivated as a medicinal plant); b fruiting twig; c flowers, unripe (green) and ripe (black) berries; Sects. 3.1 / 3.3.2 / 3.4 / 3.5 / 6.5.2 / 7.5.1 / 7.7.2 / 7.7.4.3 Plate 1d Brugmansia versicolor (angel’s trumpet): shrub or small tree (to 5 m); tropical parts of Ecuador west of the Andes (cultivated as an ornamental in tropical and subtropical regions); Sect. -

Management Plan for the South Australian Lake Eyre Basin Fisheries

MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN LAKE EYRE BASIN FISHERIES Part 1 – Commercial and recreational fisheries Part 2 – Yandruwandha Yawarrawarrka Aboriginal traditional fishery Approved by the Minister for Agriculture, Food and Fisheries pursuant to section 44 of the Fisheries Management Act 2007. Hon Gail Gago MLC Minister for Agriculture, Food and Fisheries 1 March 2013 Page 1 of 118 PIRSA Fisheries & Aquaculture (A Division of Primary Industries and Regions South Australia) GPO Box 1625 ADELAIDE SA 5001 www.pir.sa.gov.au/fisheries Tel: (08) 8226 0900 Fax: (08) 8226 0434 © Primary Industries and Regions South Australia 2013 Disclaimer: This management plan has been prepared pursuant to the Fisheries Management Act 2007 (South Australia) for the purpose of the administration of that Act. The Department of Primary Industries and Regions SA (and the Government of South Australia) make no representation, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this management plan or as to the suitability of that information for any particular purpose. Use of or reliance upon information contained in this management plan is at the sole risk of the user in all things and the Department of Primary Industries and Regions SA (and the Government of South Australia) disclaim any responsibility for that use or reliance and any liability to the user. Copyright Notice: This work is copyright. Copyright in this work is owned by the Government of South Australia. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Commonwealth), no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission of the Government of South Australia. -

Redalyc.Growth and Nutrient Uptake Patterns in Plants of Duboisia Sp

Semina: Ciências Agrárias ISSN: 1676-546X [email protected] Universidade Estadual de Londrina Brasil Cagliari Fioretto, Conrado; Tironi, Paulo; Pinto de Souza, José Roberto Growth and nutrient uptake patterns in plants of Duboisia sp Semina: Ciências Agrárias, vol. 37, núm. 4, julio-agosto, 2016, pp. 1883-1895 Universidade Estadual de Londrina Londrina, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=445749546016 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative DOI: 10.5433/1679-0359.2016v37n4p1883 Growth and nutrient uptake patterns in plants of Duboisia sp Crescimento e marcha de absorção de nutrientes em plantas de Duboisia sp Conrado Cagliari Fioretto1*; Paulo Tironi2; José Roberto Pinto de Souza3 Abstract Characterizing growth and nutrient uptake is important for the establishment of plant cultivation techniques that aim at high levels of production. The culturing of Duboisia sp., although very important for world medicine, has been poorly studied in the field, since the cultivation of this plant is restricted to a few regions. The objective of this paper is to characterize growth and nutrient absorption during development in Duboisia sp. under a commercial cultivation system, and in particular to assess the distribution of dry matter and nutrients in the leaves and branches. Our work was performed on a commercial production farm located in Arapongas, Paraná, Brazil, from March 2009 to February 2010. A total of 10 evaluations took place at approximately 10-day intervals, starting 48 days after planting and ending at harvesting, 324 days after planting. -

100 the SOUTH-WEST CORNER of QUEENSLAND. (By S

100 THE SOUTH-WEST CORNER OF QUEENSLAND. (By S. E. PEARSON). (Read at a meeting of the Historical Society of Queensland, August 27, 1937). On a clear day, looking westward across the channels of the Mulligan River from the gravelly tableland behind Annandale Homestead, in south western Queensland, one may discern a long low line of drift-top sandhills. Round more than half the skyline the rim of earth may be likened to the ocean. There is no break in any part of the horizon; not a landmark, not a tree. Should anyone chance to stand on those gravelly rises when the sun was peeping above the eastem skyline they would witness a scene that would carry the mind at once to the far-flung horizons of the Sahara. In the sunrise that western region is overhung by rose-tinted haze, and in the valleys lie the purple shadows that are peculiar to the waste places of the earth. Those naked, drift- top sanddunes beyond the Mulligan mark the limit of human occupation. Washed crimson by the rising sun they are set Kke gleaming fangs in the desert's jaws. The Explorers. The first white men to penetrate that line of sand- dunes, in south-western Queensland, were Captain Charles Sturt and his party, in September, 1845. They had crossed the stony country that lies between the Cooper and the Diamantina—afterwards known as Sturt's Stony Desert; and afterwards, by the way, occupied in 1880, as fair cattle-grazing country, by the Broad brothers of Sydney (Andrew and James) under the run name of Goyder's Lagoon—and the ex plorers actually crossed the latter watercourse with out knowing it to be a river, for in that vicinity Sturt describes it as "a great earthy plain." For forty miles one meets with black, sundried soil and dismal wilted polygonum bushes in a dry season, and forty miles of hock-deep mud, water, and flowering swamp-plants in a wet one. -

A Molecular Phylogeny of the Solanaceae

TAXON 57 (4) • November 2008: 1159–1181 Olmstead & al. • Molecular phylogeny of Solanaceae MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS A molecular phylogeny of the Solanaceae Richard G. Olmstead1*, Lynn Bohs2, Hala Abdel Migid1,3, Eugenio Santiago-Valentin1,4, Vicente F. Garcia1,5 & Sarah M. Collier1,6 1 Department of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195, U.S.A. *olmstead@ u.washington.edu (author for correspondence) 2 Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112, U.S.A. 3 Present address: Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt 4 Present address: Jardin Botanico de Puerto Rico, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Apartado Postal 364984, San Juan 00936, Puerto Rico 5 Present address: Department of Integrative Biology, 3060 Valley Life Sciences Building, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720, U.S.A. 6 Present address: Department of Plant Breeding and Genetics, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853, U.S.A. A phylogeny of Solanaceae is presented based on the chloroplast DNA regions ndhF and trnLF. With 89 genera and 190 species included, this represents a nearly comprehensive genus-level sampling and provides a framework phylogeny for the entire family that helps integrate many previously-published phylogenetic studies within So- lanaceae. The four genera comprising the family Goetzeaceae and the monotypic families Duckeodendraceae, Nolanaceae, and Sclerophylaceae, often recognized in traditional classifications, are shown to be included in Solanaceae. The current results corroborate previous studies that identify a monophyletic subfamily Solanoideae and the more inclusive “x = 12” clade, which includes Nicotiana and the Australian tribe Anthocercideae. These results also provide greater resolution among lineages within Solanoideae, confirming Jaltomata as sister to Solanum and identifying a clade comprised primarily of tribes Capsiceae (Capsicum and Lycianthes) and Physaleae. -

A Thesis Submitted by Dale Wayne Kerwin for the Award of Doctor of Philosophy 2020

SOUTHWARD MOVEMENT OF WATER – THE WATER WAYS A thesis submitted by Dale Wayne Kerwin For the award of Doctor of Philosophy 2020 Abstract This thesis explores the acculturation of the Australian landscape by the First Nations people of Australia who named it, mapped it and used tangible and intangible material property in designing their laws and lore to manage the environment. This is taught through song, dance, stories, and paintings. Through the tangible and intangible knowledge there is acknowledgement of the First Nations people’s knowledge of the water flows and rivers from Carpentaria to Goolwa in South Australia as a cultural continuum and passed onto younger generations by Elders. This knowledge is remembered as storyways, songlines and trade routes along the waterways; these are mapped as a narrative through illustrations on scarred trees, the body, engravings on rocks, or earth geographical markers such as hills and physical features, and other natural features of flora and fauna in the First Nations cultural memory. The thesis also engages in a dialogical discourse about the paradigm of 'ecological arrogance' in Australian law for water and environmental management policies, whereby Aqua Nullius, Environmental Nullius and Economic Nullius is written into Australian laws. It further outlines how the anthropocentric value of nature as a resource and the accompanying humanistic technology provide what modern humans believe is the tool for managing ecosystems. In response, today there is a coming together of the First Nations people and the new Australians in a shared histories perspective, to highlight and ensure the protection of natural values to land and waterways which this thesis also explores. -

The Key to the Nornicotine Enantiomeric Composition in Tobacco Leaf

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Plant and Soil Sciences Plant and Soil Sciences 2012 ENANTIOSELECTIVE DEMETHYLATION: THE KEY TO THE NORNICOTINE ENANTIOMERIC COMPOSITION IN TOBACCO LEAF Bin Cai University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cai, Bin, "ENANTIOSELECTIVE DEMETHYLATION: THE KEY TO THE NORNICOTINE ENANTIOMERIC COMPOSITION IN TOBACCO LEAF" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Plant and Soil Sciences. 5. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/pss_etds/5 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Plant and Soil Sciences at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Plant and Soil Sciences by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

PDF File Created from a TIFF Image by Tiff2pdf

~ I~m~III~111 200608197 CSIRO PUBLISHING www.publish.csiro.au/joumals/hras His/orical Records oJAus/ralian Science, 2006, 17, 31-69 Duboisia myoporoides: The Medical Career of a Native Australian Plant Paul Foley Prince ofWales Medical Research Institute, Barker Street, Randwick, NSW 2031, Australia. Email: [email protected] Alkaloids derived from solanaceous plants were the subject ofintense investigations by European chemists, pharmacologi~ts and clinicians in the second half ofthe nineteenth century. Some surprise was expressed when it was discovered in the 1870s that an Australian bush, Duboisia myoporoides, contained an atropine like alkaloid" 'duboisine'. A complicated and colourful history followed. Duboisine was adopted in Australia, Europe and the United States as an alternative to atropine as an ophthalmologic agent; shortly afterwards, it was also estecmed as a potent sedative in the management ofpsychiatric patients, and as an alternative to other solanaceous alkaloids in the treatment ofparkinsonism. The Second World War led to renewed interest in Duboisia species as sources of scopolamine, required for surgical anaesthesia and to manage sea-sickness, a major problem in the naval part ofthe war. As a consequence ofthe efforts of the CSIR and of Wilfrid Russell Grimwade (1879-1955), this led to the establishment of plantations in Queensland that today still supply the bulk of the world's raw scopolamine. Following the War, however, government support for commercial alkaloid extraction waned, and it was the interest ofthe German firm Boehringer Ingelheim and its investment in the industry that rescued the Duboisia industry in the mid I950s, and that continues to maintain it at a relatively low but stable level today.