Sexuality, Race, and the Limits of Self-Reflexivity in Carnival Row and the Terror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

A Sketch of the Life and Writings of Robert Knox, the Anatomist

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com ASketchoftheLifeandWritingsRobertKnox,Anatomist HenryLonsdale V ROBERT KNOX. t Zs 2>. CS^jC<^7s><7 A SKETCH LIFE AND WRITINGS ROBERT KNOX THE ANA TOM/ST. His Pupil and Colleague, HENRY LONSDALE. ITmtfora : MACMILLAN AND CO. 1870. / *All Rights reserve'*.] LONDON : R. CLAV, SONS, AND TAYLOR, PRINTERS, BREAD STREET HILL. TO SIR WILLIAM FERGUSSON, Bart. F.R.S., SERJEANT-SURGEON TO THE QUEEN, AND PRESIDENT OF THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF SURGEONS OF ENGLAND. MY DEAR FERGUSSON, I have very sincere pleasure in dedicating this volume to you, the favoured pupil, the zealous colleague, and attached friend of Dr. Robert Knox. In associating your excellent name with this Biography, I do honour to the memory of our Anatomical Teacher. I also gladly avail myself of this opportunity of paying a grateful tribute to our long and cordial friendship. Heartily rejoicing in your well-merited position as one of the leading representatives of British Surgery, I am, Ever yours faithfully, HENRY LONSDALE. Rose Hill, Carlisle, September 15, 1870. PREFACE. Shortly after the decease of Dr. Robert Knox (Dec. 1862), several friends solicited me to write his Life, but I respectfully declined, on the grounds that I had no literary experience, and that there were other pupils and associates of the Anatomist senior to myself, and much more competent to undertake his biography : moreover, I was borne down at the time by a domestic sorrow so trying that the seven years since elapsing have not entirely effaced its influence. -

2018 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By SIGNATORY COMPANY)

2018 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SIGNATORY COMPANY) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by Female Directed by Female Male Male Female Female Signatory Company Title Female + Network Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male Minority % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Unknown Unknown % Unknown Unknown % Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority 40 North Productions, LLC Looming Tower, The 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Hulu ABC Signature Studios, Inc. SMILF 8 8 100% 0 0% 0 0% 8 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Showtime ABC Studios American Housewife 24 13 54% 9 38% 2 8% 11 46% 0 0% 2 8% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios BlacK-ish 24 18 75% 6 25% 11 46% 3 13% 4 17% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Code BlacK 13 6 46% 7 54% 3 23% 2 15% 1 8% 0 0% 0 0% CBS ABC Studios Criminal Minds 22 10 45% 12 55% 4 18% 4 18% 2 9% 0 0% 0 0% CBS ABC Studios For The People 9 4 44% 5 56% 0 0% 2 22% 2 22% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Grey's Anatomy 24 16 67% 8 33% 4 17% 3 13% 9 38% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Grown-ish 13 11 85% 2 15% 7 54% 2 15% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% Freeform ABC Studios How To Get Away With 15 11 73% 4 27% 2 13% 2 13% 7 47% 0 0% 0 0% ABC Murder ABC Studios Kevin (Probably) Saves the 15 6 40% 9 60% 2 13% 4 27% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% ABC World ABC Studios Marvel's Agents of 22 11 50% 11 50% 5 23% 4 18% 2 9% 0 0% 0 0% ABC S.H.I.E.L.D. -

Eric L. Mills H.M.S. CHALLENGER, HALIFAX, and the REVEREND

529 THE DALHOUSIE REVIEW Eric L. Mills H.M.S. CHALLENGER, HALIFAX, AND THE REVEREND DR. HONEYMAN I The arrival of the British corvette Challenger in Halifax on May 9, 18 7~l. was not particularly unusual in itself. But the men on board and the purpose of the voyage were unusual, because the ship as she docked brought oceanography for the first time to Nova Scotia, and in fact was establishing that branch of science as a global, coherent discipline. The arrival of Challenger at Halifax was nearly an accident. At its previous stop, Bermuda, the ship's captain, G.S. Nares, had been warned that his next port of call, New York, was offering high wages and that he could expect many desertions. 1 Course was changed; the United States coast passed b y the port side, and Challenger steamed slowly into the early spring of Halifax Harbour. We reached Halifax on the morning of the 9th. The weather was very fine and perfectly still, w :i th a light mist, and as we steamed up the bay there was a most extraordinary and bewildering display of mirage. The sea and the land and the sky were hopelessly confused; all the objects along the shore drawn up out of all proportion, the white cottages standing out like pillars and light-house!:, and all the low rocky islands loo king as if they were crowned with battlements and towers. Low, hazy islands which had no place on the chart bounded the horizon, and faded away while one was looking at them. -

And Physicians of Southern Alberta

Medical Clinics and Physicians of Southern Alberta Gerald M. McDougall & Fiona C. Harris ~ ~ N RA 983 .A4 105 A424 1991 C.2 Medical Clinics and Physicians of Southern Alberta Gerald M. McDougall & Fiona C. Harris with Jim Middlemiss Leopold Lewis & D.S. Grant © 1991 by Gerald M. McDougall. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, by print, photocopy, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data: McDougall, Gerald M. (Gerald Millward), 1934- Medical clinics and physicians of Southern Alberta Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-83953-162-5 1. Group medical practice--Alberta--History. 2. Clinics--Alberta--History. I. Harris, Fiona C. II. Title. RA983.A4A46 1992 610'.65'09712309 C92-091727-5 Published by: G. M. McDougall 3707 Utah Drive N.W. Calgary, Alberta T2N 4A6 Printed in Canada, by the University of Calgary Printing Services. This book is dedicated to: Donald R. Wilson, MD FRCPC Professor of Medicine, University of Alberta. Edward L. Margetts, MD FRCPC Professor of Psychiatry, University of British Columbia. physicians who as clinicians, teachers, medical historians and friends had a great influence on my life, and my interest in medical education and medical history. GMMcD. FOREWORD I was asked to read the manuscript of this book in the fall of 1989. Having read Teachers of Medicine, wherein one of the present editors coordinated the work of many of the early medical educators in tracing the development of grad uate clinical education in Calgary, I was pleased to examine this new work. -

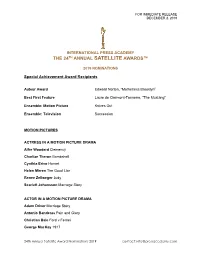

2019 IPA Nomination 24Th Satelilite FINAL 12-2-2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DECEMBER 2, 2019 INTERNATIONAL PRESS ACADEMY THE 24TH ANNUAL SATELLITE AWARDS™ 2019 NOMINATIONS Special Achievement Award Recipients Auteur Award Edward Norton, “Motherless Brooklyn” Best First Feature Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre, “The MustanG” Ensemble: Motion Picture KnIves Out Ensemble: Television Succession MOTION PICTURES ACTRESS IN A MOTION PICTURE DRAMA Alfre Woodard Clemency Charlize Theron Bombshell Cynthia Erivo Harriet Helen Mirren The Good LIar Renee Zellweger Judy Scarlett Johansson MarriaGe Story ACTOR IN A MOTION PICTURE DRAMA Adam Driver MarriaGe Story Antonio Banderas PaIn and Glory Christian Bale Ford v FerrarI George MacKay 1917 24th Annual Satellite Award Nominations 2019 contact: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DECEMBER 2, 2019 Joaquin Phoenix Joker Mark Ruffalo Dark Waters ACTRESS IN A MOTION PICTURE, COMEDY OR MUSICAL Awkwafina The Farewell Ana De Armas KnIves Out Constance Wu Hustlers Julianne Moore GlorIa Bell ACTOR IN A MOTION PICTURE, COMEDY OR MUSICAL Adam Sandler Uncut Gems Daniel Craig KnIves Out Eddie Murphy DolemIte Is My Name Leonardo DiCaprio Once Upon a Time In Hollywood Taron Egerton Rocketman Taika Waititi Jojo RabbIt ACTRESS IN A SUPPORTING ROLE Jennifer Lopez Hustlers Laura Dern MarrIaGe Story Margot Robbie Bombshell Penelope Cruz PaIn and Glory Nicole Kidman Bombshell Zhao Shuzhen The Farewell ACTOR IN A SUPPORTING ROLE Anthony Hopkins The Two Popes Brad Pitt Once Upon a Time In Hollywood Joe Pesci The IrIshman Tom Hanks A BeautIful Day In The NeiGhborhood 24th Annual Satellite Award Nominations 2019 contact: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DECEMBER 2, 2019 Willem Dafoe The LIGhthouse Wendell Pierce BurnInG Cane MOTION PICTURE, DRAMA 1917 UnIversal PIctures Bombshell Lionsgate Burning Cane Array ReleasinG Ford v Ferrari TwentIeth Century Fox Joker Warner Bros. -

A Selection of Books, Maps and Manuscripts on the Northwest Passage in the British Library

A selection of books, maps and manuscripts on the Northwest Passage in the British Library Early approaches John Cabot (1425-c1500 and Sebastian Cabot (1474-1557) "A brief somme of Geographia" includes description of a voyage made by Roger Barlow and Henry Latimer for Robert Thorne in company with Sebastian Cabot in 1526-1527. The notes on a Northern passage at the end are practically a repetition of what Thorne had advocated to the King in 1527. BL: Royal 18 B XXVIII [Manuscripts] "A note of S. Gabotes voyage of discoverie taken out of an old chronicle" / written by Robert Fabyan. In: Divers voyages touching the discouerie of America / R. H. [i.e. Richard Hakluyt]. London, 1582. BL: C.21.b.35 Between the title and signature A of this volume there are five leaves containing "The names of certaine late travaylers"etc., "A very late and great probabilitie of a passage by the Northwest part of America" and "An epistle dedicatorie ... to Master Phillip Sidney Esquire" Another copy with maps is at BL: G.6532 A memoir of Sebastian Cabot; with a review of the history of maritime discovery / [by Richard Biddle]; illustrated by documents from the Rolls, now first published. London: Hurst, Chance, 1831. 333p BL: 1202.k.9 Another copy is at BL: G.1930 and other editions include Philadelphia, 1831 at BL: 10408.f.21 and Philadelphia 1915 (with a portrait of Cabot) at BL: 10408.o.23 The remarkable life, adventures, and discoveries of Sebastian Cabot / J. F. Nicholls. London: Sampson, Low and Marston, 1869. -

Flesh on the Bones

FIFE FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY JOURNAL NEW SERIES No 34 Summer 2015 CONTENTS Contents,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,1 Editorial,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,.,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,.,,,2 Flesh On The Bones,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,, ,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,3 Crail Fishing Disaster,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,31 Miss Betty Stott,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,32 The Fife Family History Society,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,33 Waterloo,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,..,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,.34 Shorts,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,36 The Fife Gravestones Conference,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,39 The End of An Era,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,; ,,,,,,,,,,,,,40 Buffalo Bill in Kirkcaldy. ByTom Cunningham,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,42 John Goodsir. A Scottish Anatomist and Pioneer. By Michael Tracy,,,,,,,,,,,,,44 Chairman`s Report: AGM, 9 June 2015,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,62 Fife Family History Society: Accounts, 2014-15,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,64 -

Printmgr File

To our shareowners: The American Customer Satisfaction Index recently announced the results of its annual survey, and for the 8th year in a row customers ranked Amazon #1. The United Kingdom has a similar index, The U.K. Customer Satisfaction Index, put out by the Institute of Customer Service. For the 5th time in a row Amazon U.K. ranked #1 in that survey. Amazon was also just named the #1 business on LinkedIn’s 2018 Top Companies list, which ranks the most sought after places to work for professionals in the United States. And just a few weeks ago, Harris Poll released its annual Reputation Quotient, which surveys over 25,000 consumers on a broad range of topics from workplace environment to social responsibility to products and services, and for the 3rd year in a row Amazon ranked #1. Congratulations and thank you to the now over 560,000 Amazonians who come to work every day with unrelenting customer obsession, ingenuity, and commitment to operational excellence. And on behalf of Amazonians everywhere, I want to extend a huge thank you to customers. It’s incredibly energizing for us to see your responses to these surveys. One thing I love about customers is that they are divinely discontent. Their expectations are never static – they go up. It’s human nature. We didn’t ascend from our hunter-gatherer days by being satisfied. People have a voracious appetite for a better way, and yesterday’s ‘wow’ quickly becomes today’s ‘ordinary’. I see that cycle of improvement happening at a faster rate than ever before. -

Superman's Origin Story < Donald Sutherland As

3-month TV calendar Page 29 RETURNING FAVORITES WESTWORLD ELEMENTARY QUANTICO THE AMERICANS NEW GIRL She’s back. Still fearless. And still very, very funny! MUST-SEE NEW SHOWS MARCH 19–APRIL 1, 2018 Superman’s origin story DOUBLE ISSUE < Donald Sutherland as the world’s richest man Grey’s Anatomy spinoff DOUBLE ISSUE • 2 WEEKS OF LISTINGS VOLUME 66 | NUMBER 12 | ISSUE #3427–3428 In This Issue On the Cover 18 Cover Story: Roseanne The iconic family comedy is back! We check in to see what’s next for the Conner clan in ABC’s much-anticipated reboot. 22 Spring Preview Donald Sutherland stars in FX’s Trust, Zach Braff returns with Alex, Inc., Superman’s history is told in Krypton, inside Grey’s Anatomy spinoff Station 19 (Jason George, inset) and Sandra Oh faces danger in Killing Eve. Plus: Intel on Westworld, The Americans, Quantico, Elementary, The Handmaid’s Tale and New Girl. 29 Spring TV Calendar 2 Ask Matt EDITOR’S 3 Stu We Love 4 Burning Questions LETTER Yikes! What really happened on that It’s been three decades since we met the shocking Bachelor finale. 5 Ratings Conners, a working-class family from fictional Lanford, Illinois, headed up by parents Rose- 6 Crime Scene NEW! anne, a factory line worker, and Dan, a contrac- Five can’t-miss specials and shows for true-crime fans. tor. Few shows since the ’70s had focused on 8 Tastemakers characters struggling with the money prob- Valerie Bertinelli dishes on her Food Network show. Plus: Her savory lems that come with blue-collar jobs. -

ANNUAL REPORT to Our Shareowners

2017 ANNUAL REPORT To our shareowners: The American Customer Satisfaction Index recently announced the results of its annual survey, and for the 8th year in a row customers ranked Amazon #1. The United Kingdom has a similar index, The U.K. Customer Satisfaction Index, put out by the Institute of Customer Service. For the 5th time in a row Amazon U.K. ranked #1 in that survey. Amazon was also just named the #1 business on LinkedIn’s 2018 Top Companies list, which ranks the most sought after places to work for professionals in the United States. And just a few weeks ago, Harris Poll released its annual Reputation Quotient, which surveys over 25,000 consumers on a broad range of topics from workplace environment to social responsibility to products and services, and for the 3rd year in a row Amazon ranked #1. Congratulations and thank you to the now over 560,000 Amazonians who come to work every day with unrelenting customer obsession, ingenuity, and commitment to operational excellence. And on behalf of Amazonians everywhere, I want to extend a huge thank you to customers. It’s incredibly energizing for us to see your responses to these surveys. One thing I love about customers is that they are divinely discontent. Their expectations are never static – they go up. It’s human nature. We didn’t ascend from our hunter-gatherer days by being satisfied. People have a voracious appetite for a better way, and yesterday’s ‘wow’ quickly becomes today’s ‘ordinary’. I see that cycle of improvement happening at a faster rate than ever before.