History of the North American Bird Fauna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica 2020

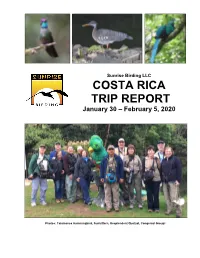

Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Photos: Talamanca Hummingbird, Sunbittern, Resplendent Quetzal, Congenial Group! Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Leaders: Frank Mantlik & Vernon Campos Report and photos by Frank Mantlik Highlights and top sightings of the trip as voted by participants Resplendent Quetzals, multi 20 species of hummingbirds Spectacled Owl 2 CR & 32 Regional Endemics Bare-shanked Screech Owl 4 species Owls seen in 70 Black-and-white Owl minutes Suzy the “owling” dog Russet-naped Wood-Rail Keel-billed Toucan Great Potoo Tayra!!! Long-tailed Silky-Flycatcher Black-faced Solitaire (& song) Rufous-browed Peppershrike Amazing flora, fauna, & trails American Pygmy Kingfisher Sunbittern Orange-billed Sparrow Wayne’s insect show-and-tell Volcano Hummingbird Spangle-cheeked Tanager Purple-crowned Fairy, bathing Rancho Naturalista Turquoise-browed Motmot Golden-hooded Tanager White-nosed Coati Vernon as guide and driver January 29 - Arrival San Jose All participants arrived a day early, staying at Hotel Bougainvillea. Those who arrived in daylight had time to explore the phenomenal gardens, despite a rain storm. Day 1 - January 30 Optional day-trip to Carara National Park Guides Vernon and Frank offered an optional day trip to Carara National Park before the tour officially began and all tour participants took advantage of this special opportunity. As such, we are including the sightings from this day trip in the overall tour report. We departed the Hotel at 05:40 for the drive to the National Park. En route we stopped along the road to view a beautiful Turquoise-browed Motmot. -

(Pycnonotidae: Andropadus) Supports a Montane Speciation Model

Recent diversi¢cation in African greenbuls (Pycnonotidae: Andropadus) supports a montane speciation model MICHAEL S. ROY Zoological Institute, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK 2100, Denmark SUMMARY It is generally accepted that accentuated global climatic cycles since the Plio-Pleistocene (2.8 Ma ago) have caused the intermittent fragmentation of forest regions into isolated refugia thereby providing a mechanism for speciation of tropical forest biota contained within them. However, it has been assumed that this mechanism had its greatest e¡ect in the species rich lowland regions. Contrary evidence from molecular studies of African and South American forest birds suggests that areas of recent intensive speciation, where mostly new lineages are clustered, occur in discrete tropical montane regions, while lowland regions contain mostly old species. Two predictions arise from this ¢nding. First, a species phylogeny of an avian group, represented in both lowland and montane habitats, should be ordered such that montane forms are represented by the most derived characters. Second, montane speciation events should predominate within the past 2.8 Ma. In order to test this model I have investigated the evolutionary history of the recently radiated African greenbuls (genus Andropadus), using a molecular approach. This analysis ¢nds that montane species are a derived monophyletic group when compared to lowland species of the same genus and recent speciation events (within the Plio-Pleistocene) have exclusively occurred in montane regions. These data support the view that montane regions have acted as centres of speciation during recent climatic instability. 1. I NTRODUCTION biodiversity of tropical lowland forests was the `refuge theory' (Ha¡er 1969, 1974; Diamond & Hamilton The most signi¢cant geological changes that a¡ected 1980; Mayr & O'Hara 1986; Crowe & Crowe 1982; re- the biota of Africa during the Tertiary were: (i) a views in Prance 1982; Whitmore & Prance 1987). -

Seabirds in the Bahamian Archipelago and Adjacent Waters

S a icds in hamian Archip I ,nd ad' c nt t rs: Tr ,nsi nt, Xx,int rin ndR,r N stin S ci s Turks and Caicos Islands. The Bahama nor and Loftin (1985) and Budcn(1987). The AnthonyW. White Islands lie as close as 92 km (50 nautical statusof nonbreedingseabirds, on the other miles)to theFlorida coast, and so, as a prac- hand,has never been reported comprehen- 6540Walhonding Road tical matter,all recordsca. 46 km or more east sivelyand is sometimesdescribed in general of Florida between Palm Beachand Miami are termssuch as "reportedand to be expected Bethesda,Maryland 20816 consideredtobe in Bahamianwaters. To pre- occasionally"(Brudenell-Brucc 1975) or "at servethe relative accuracy of thereports, dis- seaamong the Bahamas"(Bond 1993). The (email:[email protected]) tances arc citedas givenin sources,rather presentpaper compiles published and unpub- than converted into metric units. lishedreports of transientand wintering Ihc birdlife of the BahamaIslands has been seabirdsin theregion in orderto provide a bet- ABSTRACT studiedsporadical13z Landbirds have received ter understandingof theirstatus; several rare The statusof mostnonbreeding seabirds in themost attention recently, owing to increased breedingspecies are included herein as well. the BahamianArchipelago and its adjacent interestin winteringNeotropical migrants. Manyreports are foundin relativelyobscure watersis poorly understood.Much of the Breedingseabirds have also been fairly well publicationsor in personalarchives, which availableinformation isbased on sight reports documented.Sprunt (1984) provides a com- hasmeant that evenmodern-day observers unsupportedby specimensor photographic prehensivereport of breedingseabirds; Lee lackcontextual information on seabirdsthey evidence.This paper reviews published and andClark (1994) cover seabirds nesting in the seein theregion. -

Aves: Rhinocryptidae): in and out Per G

Circumscription of a monophyletic family for the tapaculos (Aves: Rhinocryptidae): in and out Per G. P. Ericson, Storrs L. Olson, Martin Irestedt, Herculano Alvarenga, Jon Fjeldså To cite this version: Per G. P. Ericson, Storrs L. Olson, Martin Irestedt, Herculano Alvarenga, Jon Fjeldså. Circumscrip- tion of a monophyletic family for the tapaculos (Aves: Rhinocryptidae): in and out. Journal für Ornithologie = Journal of Ornithology, Springer Verlag, 2009, 151 (2), pp.337-345. 10.1007/s10336- 009-0460-9. hal-00568355 HAL Id: hal-00568355 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00568355 Submitted on 23 Feb 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 2 3 4 Circumscription of a monophyletic family for the tapaculos 5 (Aves: Rhinocryptidae): Psiloramphus in and Melanopareia out 6 7 8 Per G. P. Ericson 1, 6, Storrs L. Olson 2, Martin Irestedt 3, Herculano Alvarenga 4, 9 and Jon Fjeldså 5 10 11 12 13 14 15 1 Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 16 50007, SE–10405 Stockholm, Sweden 17 18 2 Division of Birds, Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural 19 History, P.O. -

Order CHARADRIIFORMES: Waders, Gulls and Terns Suborder LARI

Text extracted from Gill B.J.; Bell, B.D.; Chambers, G.K.; Medway, D.G.; Palma, R.L.; Scofield, R.P.; Tennyson, A.J.D.; Worthy, T.H. 2010. Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. 4th edition. Wellington, Te Papa Press and Ornithological Society of New Zealand. Pages 191, 223 & 227-228. Order CHARADRIIFORMES: Waders, Gulls and Terns The family sequence of Christidis & Boles (1994), who adopted that of Sibley et al. (1988) and Sibley & Monroe (1990), is followed here. Suborder LARI: Skuas, Gulls, Terns and Skimmers Condon (1975) and Checklist Committee (1990) recognised three subfamilies within the Laridae (Larinae, Sterninae and Megalopterinae) but this division has not been widely adopted. We follow Gochfeld & Burger (1996) in recognising gulls in one family (Laridae) and terns and noddies in another (Sternidae). The sequence of species for Stercorariidae and Laridae follows Peters (1934) and for Sternidae follows Bridge et al. (2005). Family LARIDAE Rafinesque: Gulls Laridia Rafinesque, 1815: Analyse de la Nature: 72 – Type genus Larus Linnaeus, 1758. Genus Larus Linnaeus Larus Linnaeus, 1758: Syst. Nat., 10th edition 1: 136 – Type species (by subsequent designation) Larus marinus Linnaeus. Gavia Boie, 1822: Isis von Oken, Heft 10: col. 563 – Type species (by subsequent designation) Larus ridibundus Linnaeus. Junior homonym of Gavia Moehring, 1758. Hydrocoleus Kaup, 1829: Skizz. Entw.-Gesch. Eur. Thierw.: 113 – Type species (by subsequent designation) Larus minutus Linnaeus. Chroicocephalus Eyton, 1836: Cat. Brit. Birds: 53 – Type species (by monotypy) Larus cucullatus Reichenbach = Larus pipixcan Wagler. Gelastes Bonaparte, 1853: Journ. für Ornith. -

Birdlife International for the Input of Analyses, Technical Information, Advice, Ideas, Research Papers, Peer Review and Comment

UNEP/CMS/ScC16/Doc.10 Annex 2b CMS Scientific Council: Flyway Working Group Reviews Review 2: Review of Current Knowledge of Bird Flyways, Principal Knowledge Gaps and Conservation Priorities Compiled by: JEFF KIRBY Just Ecology Brookend House, Old Brookend, Berkeley, Gloucestershire, GL13 9SQ, U.K. June 2010 Acknowledgements I am grateful to colleagues at BirdLife International for the input of analyses, technical information, advice, ideas, research papers, peer review and comment. Thus, I extend my gratitude to my lead contact at the BirdLife Secretariat, Ali Stattersfield, and to Tris Allinson, Jonathan Barnard, Stuart Butchart, John Croxall, Mike Evans, Lincoln Fishpool, Richard Grimmett, Vicky Jones and Ian May. In addition, John Sherwell worked enthusiastically and efficiently to provide many key publications, at short notice, and I’m grateful to him for that. I also thank the authors of, and contributors to, Kirby et al. (2008) which was a major review of the status of migratory bird species and which laid the foundations for this work. Borja Heredia, from CMS, and Taej Mundkur, from Wetlands International, also provided much helpful advice and assistance, and were instrumental in steering the work. I wish to thank Tim Jones as well (the compiler of a parallel review of CMS instruments) for his advice, comment and technical inputs; and also Simon Delany of Wetlands International. Various members of the CMS Flyway Working Group, and other representatives from CMS, BirdLife and Wetlands International networks, responded to requests for advice and comment and for this I wish to thank: Olivier Biber, Joost Brouwer, Nicola Crockford, Carlo C. Custodio, Tim Dodman, Roger Jaensch, Jelena Kralj, Angus Middleton, Narelle Montgomery, Cristina Morales, Paul Kariuki Ndang'ang'a, Paul O’Neill, Herb Raffaele and David Stroud. -

Borneo: Broadbills & Bristleheads

TROPICAL BIRDING Trip Report: BORNEO June-July 2012 A Tropical Birding Set Departure Tour BORNEO: BROADBILLS & BRISTLEHEADS RHINOCEROS HORNBILL: The big winner of the BIRD OF THE TRIP; with views like this, it’s easy to understand why! 24 June – 9 July 2012 Tour Leader: Sam Woods All but one photo (of the Black-and-yellow Broadbill) were taken by Sam Woods (see http://www.pbase.com/samwoods or his blog, LOST in BIRDING http://www.samwoodsbirding.blogspot.com for more of Sam’s photos) 1 www.tropicalbirding.com Tel: +1-409-515-0514 E-mail: [email protected] TROPICAL BIRDING Trip Report: BORNEO June-July 2012 INTRODUCTION Whichever way you look at it, this year’s tour of Borneo was a resounding success: 297 bird species were recorded, including 45 endemics . We saw all but a few of the endemic birds we were seeking (and the ones missed are mostly rarely seen), and had good weather throughout, with little rain hampering proceedings for any significant length of time. Among the avian highlights were five pitta species seen, with the Blue-banded, Blue-headed, and Black-and-crimson Pittas in particular putting on fantastic shows for all birders present. The Blue-banded was so spectacular it was an obvious shoe-in for one of the top trip birds of the tour from the moment we walked away. Amazingly, despite absolutely stunning views of a male Blue-headed Pitta showing his shimmering cerulean blue cap and deep purple underside to spectacular effect, he never even got a mention in the final highlights of the tour, which completely baffled me; he simply could not have been seen better, and birds simply cannot look any better! However, to mention only the endemics is to miss the mark, as some of the, other, less local birds create as much of a stir, and can bring with them as much fanfare. -

Karl Jordan: a Life in Systematics

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Kristin Renee Johnson for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of SciencePresented on July 21, 2003. Title: Karl Jordan: A Life in Systematics Abstract approved: Paul Lawrence Farber Karl Jordan (1861-1959) was an extraordinarily productive entomologist who influenced the development of systematics, entomology, and naturalists' theoretical framework as well as their practice. He has been a figure in existing accounts of the naturalist tradition between 1890 and 1940 that have defended the relative contribution of naturalists to the modem evolutionary synthesis. These accounts, while useful, have primarily examined the natural history of the period in view of how it led to developments in the 193 Os and 40s, removing pre-Synthesis naturalists like Jordan from their research programs, institutional contexts, and disciplinary homes, for the sake of synthesis narratives. This dissertation redresses this picture by examining a naturalist, who, although often cited as important in the synthesis, is more accurately viewed as a man working on the problems of an earlier period. This study examines the specific problems that concerned Jordan, as well as the dynamic institutional, international, theoretical and methodological context of entomology and natural history during his lifetime. It focuses upon how the context in which natural history has been done changed greatly during Jordan's life time, and discusses the role of these changes in both placing naturalists on the defensive among an array of new disciplines and attitudes in science, and providing them with new tools and justifications for doing natural history. One of the primary intents of this study is to demonstrate the many different motives and conditions through which naturalists came to and worked in natural history. -

US Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan—Pacific Region

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan Conservation Seabird Pacific Region U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan—Pacific Region 120 0’0"E 140 0’0"E 160 0’0"E 180 0’0" 160 0’0"W 140 0’0"W 120 0’0"W 100 0’0"W RUSSIA CANADA 0’0"N 0’0"N 50 50 WA CHINA US Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Region OR ID AN NV JAP CA H A 0’0"N I W 0’0"N 30 S A 30 N L I ort I Main Hawaiian Islands Commonwealth of the hwe A stern A (see inset below) Northern Mariana Islands Haw N aiian Isla D N nds S P a c i f i c Wake Atoll S ND ANA O c e a n LA RI IS Johnston Atoll MA Guam L I 0’0"N 0’0"N N 10 10 Kingman Reef E Palmyra Atoll I S 160 0’0"W 158 0’0"W 156 0’0"W L Howland Island Equator A M a i n H a w a i i a n I s l a n d s Baker Island Jarvis N P H O E N I X D IN D Island Kauai S 0’0"N ONE 0’0"N I S L A N D S 22 SI 22 A PAPUA NEW Niihau Oahu GUINEA Molokai Maui 0’0"S Lanai 0’0"S 10 AMERICAN P a c i f i c 10 Kahoolawe SAMOA O c e a n Hawaii 0’0"N 0’0"N 20 FIJI 20 AUSTRALIA 0 200 Miles 0 2,000 ES - OTS/FR Miles September 2003 160 0’0"W 158 0’0"W 156 0’0"W (800) 244-WILD http://www.fws.gov Information U.S. -

The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan

The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan A Strategy for Protecting and Managing Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Habitats and Associated Birds in California A Project of California Partners in Flight and PRBO Conservation Science The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan A Strategy for Protecting and Managing Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Habitats and Associated Birds in California Version 2.0 2004 Conservation Plan Authors Grant Ballard, PRBO Conservation Science Mary K. Chase, PRBO Conservation Science Tom Gardali, PRBO Conservation Science Geoffrey R. Geupel, PRBO Conservation Science Tonya Haff, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at Museum of Natural History Collections, Environmental Studies Dept., University of CA) Aaron Holmes, PRBO Conservation Science Diana Humple, PRBO Conservation Science John C. Lovio, Naval Facilities Engineering Command, U.S. Navy (Currently at TAIC, San Diego) Mike Lynes, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at Hastings University) Sandy Scoggin, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at San Francisco Bay Joint Venture) Christopher Solek, Cal Poly Ponoma (Currently at UC Berkeley) Diana Stralberg, PRBO Conservation Science Species Account Authors Completed Accounts Mountain Quail - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Greater Roadrunner - Pete Famolaro, Sweetwater Authority Water District. Coastal Cactus Wren - Laszlo Szijj and Chris Solek, Cal Poly Pomona. Wrentit - Geoff Geupel, Grant Ballard, and Mary K. Chase, PRBO Conservation Science. Gray Vireo - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Black-chinned Sparrow - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Costa's Hummingbird (coastal) - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Sage Sparrow - Barbara A. Carlson, UC-Riverside Reserve System, and Mary K. Chase. California Gnatcatcher - Patrick Mock, URS Consultants (San Diego). Accounts in Progress Rufous-crowned Sparrow - Scott Morrison, The Nature Conservancy (San Diego). -

Wild Turkey Education Guide

Table of Contents Section 1: Eastern Wild Turkey Ecology 1. Eastern Wild Turkey Quick Facts………………………………………………...pg 2 2. Eastern Wild Turkey Fact Sheet………………………………………………….pg 4 3. Wild Turkey Lifecycle……………………………………………………………..pg 8 4. Eastern Wild Turkey Adaptations ………………………………………………pg 9 Section 2: Eastern Wild Turkey Management 1. Wild Turkey Management Timeline…………………….……………………….pg 18 2. History of Wild Turkey Management …………………...…..…………………..pg 19 3. Modern Wild Turkey Management in Maryland………...……………………..pg 22 4. Managing Wild Turkeys Today ……………………………………………….....pg 25 Section 3: Activity Lesson Plans 1. Activity: Growing Up WILD: Tasty Turkeys (Grades K-2)……………..….…..pg 33 2. Activity: Calling All Turkeys (Grades K-5)………………………………..…….pg 37 3. Activity: Fit for a Turkey (Grades 3-5)…………………………………………...pg 40 4. Activity: Project WILD adaptation: Too Many Turkeys (Grades K-5)…..…….pg 43 5. Activity: Project WILD: Quick, Frozen Critters (Grades 5-8).……………….…pg 47 6. Activity: Project WILD: Turkey Trouble (Grades 9-12………………….……....pg 51 7. Activity: Project WILD: Let’s Talk Turkey (Grades 9-12)..……………..………pg 58 Section 4: Additional Activities: 1. Wild Turkey Ecology Word Find………………………………………….…….pg 66 2. Wild Turkey Management Word Find………………………………………….pg 68 3. Turkey Coloring Sheet ..………………………………………………………….pg 70 4. Turkey Coloring Sheet ..………………………………………………………….pg 71 5. Turkey Color-by-Letter……………………………………..…………………….pg 72 6. Five Little Turkeys Song Sheet……. ………………………………………….…pg 73 7. Thankful Turkey…………………..…………………………………………….....pg 74 8. Graph-a-Turkey………………………………….…………………………….…..pg 75 9. Turkey Trouble Maze…………………………………………………………..….pg 76 10. What Animals Made These Tracks………………………………………….……pg 78 11. Drinking Straw Turkey Call Craft……………………………………….….……pg 80 Section 5: Wild Turkey PowerPoint Slide Notes The facilities and services of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources are available to all without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin or physical or mental disability. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma