The Intersection of Musical Identity, Record Promotion and College Radio Programming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCIENTIFIC ANALYSIS of an ARTIFACT from a PRESUMED EPISODE of SPONTANEOUS HUMAN COMBUSTION: a Possible Cllse for Biological Nuclear Reactions

Report SCIENTIFIC ANALYSIS OF AN ARTIFACT FROM A PRESUMED EPISODE OF SPONTANEOUS HUMAN COMBUSTION: A Possible CllSe for Biological Nuclear Reactions M. Sue Benford, R.N., M.A. & Larry E. Arnold ABSTRACT Spontaneous Human Combustion (SHC) is defined as a phenomenon that causes a human body to burn without a known, identifiable ignition source external to the body. While science recognizes scores of materials that can spontaneously combust, the human body is not among them. Although numerous theories have been posited to explain SHC, very little, if any, detailed scientific analysis of an actual SHC artifact has occurred. This study was designed to scientif ically evaluate a known SHC artifact (Mott book jacket) and compare the findings to those of an identical book jacket (control sample). The results indicated significant visual, microscopic, atomic and molecular differences between the blackened front cover of the Mott book jacket and the unaffected back cover. The authors posit a theory for the idiopathic thermogenic event involving a biologically-induced nuclear explosion. This theory is capable of explaining most, if not all, of the scientific findings. KEYWORDS: Spontaneous combustion, biological, nuclear, reaction Subtle Energies & Energy Medicine • Volume 8 • Number 3 • Page 195 BACKGROUND pontaneous Human Combustion (SHC) is defined as a phenomenon that causes a human body to blister, smoke, or burn without a known, Sidentifiable ignition source external to that body. While science recognizes scores of materials that can spontaneously combust under certain conditions, such as damp hay, linseed oil-soaked fabric, and the water-reactive metal magnesium, the human body is not among them. -

In Memoriam 2018: Military Figures We Lost

In Memoriam 2018: Military Figures We Lost Farewell: Remembering Those Who Died in 2018 19.6K At the close of 2018, it's time to remember some of the notable service members we lost through the year. Military Times remembers some of those who served and made their mark on the military and their country. In Memoriam 2018: Military figures we lost JANUARY Thomas Ellis, left, joins his fellow Tuskegee Airmen as they answer questions from the audience during an event at Joint Base San Antonio-Randolph Air Force Base, Texas, Feb. 8, 2010. Former Sgt. Maj. Thomas Ellis, 97: He was one of six Tuskegee Airmen living in the San Antonio area when he died. He was drafted in 1942 and later spoke with pride in his unit — the first all-black Army Air Forces unit. “They had the cream of the crop in our outfit because we had to do everything better than the other outfits,” he said during a 2010 event honoring the Tuskegee Airmen. “No one will ever beat our record.” Jan. 2. In this April 1972 photo made available by NASA, John Young salutes the U.S. flag at the Descartes landing site on the moon during the first Apollo 16 extravehicular activity. NASA says the astronaut, who walked on the moon and later commanded the first space shuttle flight, died on Friday, Jan. 5, 2018. He was 87. John Young, 87: After an early career as a Navy officer who flew the F-4 Phantom II, Young became one of NASA’s pioneers and one of a select few to walk on the moon. -

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems OSHA 3256-09R 2015 Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 “To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health.” This publication provides a general overview of a particular standards- related topic. This publication does not alter or determine compliance responsibilities which are set forth in OSHA standards and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Moreover, because interpretations and enforcement policy may change over time, for additional guidance on OSHA compliance requirements the reader should consult current administrative interpretations and decisions by the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission and the courts. Material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced, fully or partially, without permission. Source credit is requested but not required. This information will be made available to sensory-impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 693-1999; teletypewriter (TTY) number: 1-877-889-5627. This guidance document is not a standard or regulation, and it creates no new legal obligations. It contains recommendations as well as descriptions of mandatory safety and health standards. The recommendations are advisory in nature, informational in content, and are intended to assist employers in providing a safe and healthful workplace. The Occupational Safety and Health Act requires employers to comply with safety and health standards and regulations promulgated by OSHA or by a state with an OSHA-approved state plan. -

Course Descriptions Course Descriptions - 155

Course Descriptions SANTA MONICA COLLEGE CATALOG 2020–2021 155 How to Read the Course Descriptions Course Number and Name Classes that must be completed prior to taking this course. FILM 33, Making the Short Film 3 units Units of Credit Transfer: UC, CSU • Prerequisite: Film Studies 32. Classes that must • Corequisite: Film Studies 33L. be taken in the In this course, students go through the process of making same semester as a short narrative film together, emulating a professional this course. working environment. Supervised by their instructor, stu- dents develop, pre-produce, rehearse, shoot, and edit scenes from an original screenplay that is filmed in its C-ID is a course entirety in the lab component course (Film 33L) at the end numbering system of the semester. used statewide for lower-division, trans- ferable courses that Course are part of the AA-T or Transferability GEOG 1, Physical Geography 3 units AS-T degree. Transfer: UC*, CSU C-ID: GEOG 110. IGETC stands for IGETC AREA 5 (Physical Sciences, non-lab) Course Descriptions Recommended class Intersegmental • Prerequisite: None. to be completed General Education • Skills Advisory: Eligibility for English 1. Transfer Curriculum. before taking this *Maximum credit allowed for Geography 1 and 5 is one course. This is the most course (4 units). common method of This course surveys the distribution and relationships of satisfying a particular environmental elements in our atmosphere, lithosphere, UC and CSU general hydrosphere and biosphere, including weather, climate, Brief Course education transfer water resources, landforms, soils, natural vegetation, and requirement category. Description wildlife. Focus is on the systems and cycles of our natural world, including the effects of the sun and moon on envi- ronmental processes, and the roles played by humans. -

Gas Ranges Power

Gas Ranges power. This is one of the very few brands that allow you to use the oven without electricity. There are 12 different battery spark models and 12 different thermocouple system models avail- able (including 5 Pro-Series models). Available colors are white, biscuit or black. They are Peerless-Premier Gas Ranges shipped freight prepaid from the factory in 906-001 Please Select Model from Below Illinois. Freight charges are $150 to a business Peerless now offers two specific types of gas address or $200 to a home address. ranges specifically for off-grid or otherwise alter- The best part is that Peerless ranges have an native energy homes. The “T” models have a excellent reputation for very high quality. They TJK-240OP fully electronic 110V ignition system which come with a lifetime warranty on top burners allows both the top burners and the oven to be lit and have many standard quality features: with a match if the power is off. The “B” models l Recessed Porcelain Cooktop utilizes 8 “AA” batteries for spark ignition. l Universal Valves (easily convert to LP gas) Neither type utilizes a glow bar which requires a l Push-to-Turn, Blade Type, Burner Knobs lot of electrical energy to l Keep Warm 150o Thermostat operate. For the “T” mod- l Permanent Markings On Control Panel Inlay els, if your inverter is l A Full 25” Oven in 30” & 36” Ranges “on”, just turn on the l Oven Indicator Light on 30” l oven or top burner and it Lift-Off oven Door TMK-240OP lights automatically, using l Closed Door Variable Broil very little power. -

Town of Mcclellanville Mcclellanville Pedestrian Bridge Over Jeremy Creek LPA Project No

DocuSign Envelope ID: C0C76F0A-599E-40C8-97B3-1B3B9AC74447 Contract Documents & Specifications Town of McClellanville McClellanville Pedestrian Bridge over Jeremy Creek LPA Project No. 11-13 October 21, 2019 5790 Casper Padgett Way North Charleston, SC 29406 Bid Document Set No. _____ Engineer of Record 10/21/2019 421 Wando Park Blvd. Suite 210 Mt. Pleasant, SC 29464 © 2019 CDM Smith LPA 11-13 All Rights Reserved October 21, 2019 SECTION 00010 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. of Section Pages Title Page.................................................................................................................. 1 00010 Table of Contents ..................................................................................................... 3 00020 Invitation to Bid ........................................................................................................ 2 00100 Instructions to Bidders .............................................................................................. 7 ARTICLE 1. .............................................................. QUALIFICATIONS OF BIDDERS ARTICLE 2. ................................................... COPIES OF CONTRACT DOCUMENTS ARTICLE 3. .................. EXAMINATION OF CONTRACT DOCUMENTS AND SITE ARTICLE 4. ................................................................................... INTERPRETATIONS ARTICLE 7. .............................. PERFORMANCE, PAYMENT AND OTHER BONDS ARTICLE 8. ................................................................................................... -

Coping Strategies: Three Decades of Vietnam War in Hollywood

Coping Strategies: Three Decades of Vietnam War in Hollywood EUSEBIO V. LLÁCER ESTHER ENJUTO The Vietnam War represents a crucial moment in U.S. contemporary history and has given rise to the conflict which has so intensively motivated the American film industry. Although some Vietnam movies were produced during the conflict, this article will concentrate on the ones filmed once the war was over. It has been since the end of the war that the subject has become one of Hollywood's best-sellers. Apocalypse Now, The Return, The Deer Hunter, Rambo or Platoon are some of the titles that have created so much controversy as well as related essays. This renaissance has risen along with both the electoral success of the conservative party, in the late seventies, and a change of attitude in American society toward the recently ended conflict. Is this a mere coincidence? How did society react to the war? Do Hollywood movies affect public opinion or vice versa? These are some of the questions that have inspired this article, which will concentrate on the analysis of popular films, devoting a very brief space to marginal cinema. However, a general overview of the conflict it self and its repercussions, not only in the soldiers but in the civilians back in the United States, must be given in order to comprehend the between and the beyond the lines of the films about Vietnam. Indochina was a French colony in the Far East until its independence in 1954, when the dictator Ngo Dinh Diem took over the government of the country with the support of the United States. -

Russian Red in San Francisco SAN FRANCISCO

MUSIC Russian Red in San Francisco SAN FRANCISCO Thu, October 16, 2014 8:00 pm Venue The Independent, 628 Divisadero St, San Francisco, CA 94117 View map Phone: 415-771-1421 Admission Buy tickets. Doors open at 7:30 pm- More information Russian Red Credits The Spanish singer tours the U.S. and Canada to present her U.S. tour organized by The Windish third album ‘Agent Cooper.’ Agency, Charco and Sony Music Entertainment España S.L. Image courtesy of the artist. During the last few years Russian Red has become one of the most renowned artists in the Spanish music scene. Russian Red’s singer, Lourdes Hernández, has an exceptional voice and an innate ability to communicate and captivate a variety of audiences. She broke through the music scene in 2008 and became THE indie phenomenon with her debut album I Love Your Glasses (achieving a Gold record in Spain) and soon began performing on the main Spanish stages (Primavera Sound Festival, FIB, Jazzaldia, among many others), and reaching audiences in the USA, Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Argentina, Costa Rica, Germany, Holland, Belgium, etc. In 2011 she released her second LP, Fuerteventura (with Sony Music) thus taking a big leap forward in her career. Produced by Tony Doogan (Belle & Sebastian, Mogwai, David Byrne, etc.) and recorded with Stevie Jackson, Bob Kildea and Richard Colburn from Belle & Sebastian, Fuerteventura debuted at #2 on the topselling albums charts in Spain, where it stood for over 39 weeks, consolidating her position as one of the most outstanding and international Spanish artists. Russian Red rounded the year off taking home the MTV EMA Award as “Best Spanish Artist.” Fuerteventura was not only a great success in Spain, but it also launched Russian Red onto the international scene, placing her in the international bands spectrum. -

Bears Volleyball Win Regional Tourney Beat Kirkwood, Advance to Nationals the Bears Volleyball Won the IJCAA Region XI B Tournament in Creston, Iowa Over the Weekend

Des MOINES AREA COMMUNITY COLLEGE BOONE CAMPUS wednesday, Nov. 7 Vol. 7, No. 5 Bears volleyball win regional tourney beat Kirkwood, advance to Nationals The Bears volleyball won the IJCAA Region XI B tournament in Creston, Iowa over the weekend. In the first round, the Bears dropped Southeastern in three, 30- 14, 30-19, 30-16. The Bears knocked off longtime rival Kirkwood in three 30-23, 30-22, 30-25 to win the regional tournament and advance to the national tournament. The Bears will be in Scottsdale, Ariz. for the NJCAA Division II National Tournament Nov. 15-17. Shelby DeNeice and Kaitlyn DeVries led the team in kills agains Kirkwood with 14 and 12 respectively. Kayla Knobbe racked up 41 assists against Kirkwood. Photo: Eric Ver Helst Young Roland mayor runs for re-election Photos: Tim Larson Sam Juhl, the 20 year old mayor of Roland, wraps up his first term in office this week. Juhl is running for mayor again this year. Results of the election are expected sometime today Molly Lumley of the city council because of in politics. “He the kind of guy to me ‘I get my Social Security water-tower fight. Two neighbors Banner Staff Writer his age, but doesn’t have that that would talk politics with you check and the more you take out didn’t really like each other, problem anymore. when you were two, I’ve grown of that check, the less I’m able to and they were both neighbors On Nov. 6, the citizens of “After I graduated [from up listening to him.” He said live. -

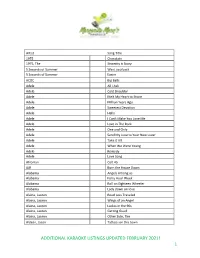

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

Music Rights Specialists

Live Festival Recordings Promotional & Commercial Opportunities 1. Live Webcast Performances will be streamed through the at&t blue room (blueroom.att.com) with a prominent link directly from the festival website (www.lollapalooza.com - 3.3 million unique visitors / 16.1 million page views in 2006) ! 117,000 unique viewers of last year’s Lollaplaooza webcast ! During the performance, a link to your band’s website will be prominently featured in the blue room media player ! Past blue room participants include Dave Matthews Band, The Killers, Bjork, Depeche Mode, Tom Petty, Oasis, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Trey Anastasio, Bloc Party, Jack Johnson, The Pixies, Widespread Panic, My Morning Jacket, Franz Ferdinand, The Arcade Fire, Arctic Monkeys and many more ! at&t provides major online & radio promotion for the webcast – over 43 million impressions o Extensive online media buys on sites such as Real Networks, MP3.com, Jam Base, Pandora, Billboard, and more o Radio promo in major markets throughout the country Online feedback from fans who watched performances from previous Lollapalooza and Austin City Limits Music Festivals on the at&t blue room: “This is the best idea I have seen for a live music festival ever! I have already bought several CDs and songs based on the performances.” “Keep up the great work! It is amazing because you can hear SOOOO clearly and no noise, wind, screams, etc....It is the best streaming presentation I have ever seen. Upclose, clear and very very easy to use. It is perfect and plays no matter what other apps are running on the computer! I LOVE it! I'm looking forward to more, especially more performances next year at ACL music festival. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO.