The Way Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plusinside Senti18 Cmufilmfest15

Pittsburgh Opera stages one of the great war horses 12 PLUSINSIDE SENTI 18 CMU FILM FEST 15 ‘BLOODLINE’ 23 WE-2 +=??B/<C(@ +,B?*(2.)??) & THURSDAY, MARCH 19, 2015 & WWW.POST-GAZETTE.COM Weekend Editor: Scott Mervis How to get listed in the Weekend Guide: Information should be sent to us two weeks prior to publication. [email protected] Send a press release, letter or flier that includes the type of event, date, address, time and phone num- Associate Editor: Karen Carlin ber of venue to: Weekend Guide, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 34 Blvd. of the Allies, Pittsburgh 15222. Or fax THE HOT LIST [email protected] to: 412-263-1313. Sorry, we can’t take listings by phone. Email: [email protected] If you cannot send your event two weeks before publication or have late material to submit, you can post Cover design by Dan Marsula your information directly to the Post-Gazette website at http://events.post-gazette.com. » 10 Music » 14 On the Stage » 15 On Film » 18 On the Table » 23 On the Tube Jeff Mattson of Dark Star City Theatre presents the Review of “Master Review of Senti; Munch Rob Owen reviews the new Orchestra gets on board for comedy “Oblivion” by Carly Builder,”opening CMU’s film goes to Circolo. Netflix drama “Bloodline.” the annual D-Jam show. Mensch. festival; festival schedule. ALL WEEKEND SUNDAY Baroque Coffee House Big Trace Johann Sebastian Bach used to spend his Friday evenings Trace Adkins, who has done many a gig opening for Toby at Zimmermann’s Coffee House in Leipzig, Germany, where he Keith, headlines the Palace Theatre in Greensburg Sunday. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

2021 Anthology

CREATING SPACES 2021 A collection of the winning writings of the 2021 writing competition entitled Creating Spaces: Giving Voice to the Youth of Minnesota Cover Art: Ethan & Kitty Digital Photography by Sirrina Martinez, SMSU alumna Cover Layout: Marcy Olson Assistant Director of Communications & Marketing Southwest Minnesota State University COPYRIGHT © 2021 Creating Spaces: Giving Voice to the Youth of Minnesota is a joint project of Southwest Minnesota State University’s Creative Writing Program and SWWC Service Cooperative. Copyright reverts to authors upon publication. Note to Readers: Some of the works in Creating Spaces may not be appropriate for a younger reading audience. CONTENTS GRADES 3 & 4 Poetry Emma Fosso The Snow on the Trees 11 Norah Siebert A Scribble 12 Teo Winger Juggling 13 Fiction Brekyn Klarenbeek Katy the Super Horse 17 Ryker Gehrke The Journey of Color 20 Penni Moore Friends Forever 35 GRADES 5 & 6 Poetry Royalle Siedschlag Night to Day 39 Addy Dierks When the Sun Hides 40 Madison Gehrke Always a Kid 41 Fiction Lindsey Setrum The Secret Trail 45 Lindsey Setrum The Journey of the Wild 47 Ava Lepp A Change of Heart 52 Nonfiction Addy Dierks Thee Day 59 Brystol Teune My Washington, DC Trip 61 Alexander Betz My Last Week Fishing with my Great Grandpa 65 GRADES 7 & 8 Poetry Brennen Thooft Hoot 69 Kelsey Hinkeldey Discombobulating 70 Madeline Prentice Six-Word Story 71 Fiction Evie Simpson A Dozen Roses 75 Keira DeBoer Life before Death 85 Claire Safranski Asylum 92 Nonfiction Mazzi Moore One Moment Can Pave Your Future -

New UT Ad Campaign Debuts of the Grounds Department, Local Weather

UTwww.utnews.utoledo.edu NEWSNOV. 5, 2007 VOLUME 8, ISSUE 12 Winter weather ahead: Know UT’s snow policy By Jim Winkler ith winter approaching, UT Wemployees should familiarize themselves with the University’s inclement weather plans. In the event of a major snow or ice storm or other inclement weather, the University will announce class cancellations, delay of classes and changes to administrative office hours through the UT home page at www.utnews.utoledo.edu, the UT snow line, which is 419.530. SNOW (7669), and on local radio and television stations. The University’s policy is to remain open whenever possible to minimize interruption of teaching and research. A decision to close UT or open late due to weather will be based on campus and area road conditions, and reports of local weather Photo by Daniel Miller forecasters and local transit. Every effort AUTUMN MORNING: UT Photographer Daniel Miller took this photo of the sun coming up over Main Campus last week. will be made to decide by 7 a.m. Using early information about conditions on campuses gathered by University police officers and members From 1872 to you: New UT ad campaign debuts of the Grounds Department, local weather By Deanna Woolf forecasts and consultations with city and county safety officials, UT Interim Senior n the streets, on the airwaves and in John Adams, senior director of the Univer- radio spots, and I think they really brought Vice President for Administration and Othe papers, The University of Toledo sity Office of Marketing. “The theme of the out the spirit and energy of UT.” Finance William Logie and the provosts is rolling out its new advertising campaign. -

English Renaissance

1 ENGLISH RENAISSANCE Unit Structure: 1.0 Objectives 1.1 The Historical Overview 1.2 The Elizabethan and Jacobean Ages 1.2.1 Political Peace and Stability 1.2.2 Social Development 1.2.3 Religious Tolerance 1.2.4 Sense and Feeling of Patriotism 1.2.5 Discovery, Exploration and Expansion 1.2.6 Influence of Foreign Fashions 1.2.7 Contradictions and Set of Oppositions 1.3 The Literary Tendencies of the Age 1.3.1 Foreign Influences 1.3.2 Influence of Reformation 1.3.3 Ardent Spirit of Adventure 1.3.4 Abundance of Output 1.4 Elizabethan Poetry 1.4.1 Love Poetry 1.4.2 Patriotic Poetry 1.4.3 Philosophical Poetry 1.4.4 Satirical Poetry 1.4.5 Poets of the Age 1.4.6 Songs and Lyrics in Elizabethan Poetry 1.4.7 Elizabethan Sonnets and Sonneteers 1.5 Elizabethan Prose 1.5.1 Prose in Early Renaissance 1.5.2 The Essay 1.5.3 Character Writers 1.5.4 Religious Prose 1.5.5 Prose Romances 2 1.6 Elizabethan Drama 1.6.1 The University Wits 1.6.2 Dramatic Activity of Shakespeare 1.6.3 Other Playwrights 1.7. Let‘s Sum up 1.8 Important Questions 1.0. OBJECTIVES This unit will make the students aware with: The historical and socio-political knowledge of Elizabethan and Jacobean Ages. Features of the ages. Literary tendencies, literary contributions to the different of genres like poetry, prose and drama. The important writers are introduced with their major works. With this knowledge the students will be able to locate the particular works in the tradition of literature, and again they will study the prescribed texts in the historical background. -

Bobby in Movieland Father Francis J

Xavier University Exhibit Father Francis J. Finn, S.J. Books Archives and Library Special Collections 1921 Bobby in Movieland Father Francis J. Finn S.J. Xavier University - Cincinnati Follow this and additional works at: http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/finn Recommended Citation Finn, Father Francis J. S.J., "Bobby in Movieland" (1921). Father Francis J. Finn, S.J. Books. Book 6. http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/finn/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Library Special Collections at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Father Francis J. Finn, S.J. Books by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • • • In perfect good faith Bobby stepped forward, passed the dir ector, saying as he went, "Excuse me, sir,'' and ignoring Comp ton and the "lady" and "gentleman," strode over to the bellhop. -Page 69. BOBBY IN MO VI ELAND BY FRANCIS J. FINN, S.J. Author of "Percy Wynn," "Tom Playfair," " Harry Dee," etc. BENZIGER BROTHERS NEw Yonx:, Cmcnrn.ATI, Cmc.AGO BENZIGER BROTHERS CoPYlUGBT, 1921, BY B:n.NZIGEB BnoTHERS Printed i11 the United States of America. CONTENTS CHAPTER 'PAGB I IN WHICH THE FmsT CHAPTER Is WITHIN A LITTLE OF BEING THE LAST 9 II TENDING TO SHOW THAT MISFOR- TUNES NEVER COME SINGLY • 18 III IT NEVER RAINS BUT IT PouRs • 31 IV MRs. VERNON ALL BUT ABANDONS Ho PE 44 v A NEW WAY OF BREAKING INTO THE M~~ ~ VI Bonny ENDEA vo:r:s TO SH ow THE As TONISHED CoMPTON How TO BE- HAVE 72 VII THE END OF A DAY OF SURPRISES 81 VIII BonnY :MEETS AN ENEMY ON THE BOULEVARD AND A FRIEND IN THE LANTRY STUDIO 92 IX SHOWING THAT IMITATION Is NOT AL WAYS THE SINCEREST FLATTERY, AND RETURNING TO THE MISAD- VENTURES OF BonBY's MoTHER. -

Teacher's Guide

National Park Service Aram Demirjian, Music Director Great Smoky Mountains National Park Sheena McCall Young People’s Concerts: Fall 2020 TEACHER’S GUIDE THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK (INSIDE COVER) Table of Contents PROGRAM REPERTOIRE Program Notes: Our Composers and their Music “Reel Time” from Southern Harmony Higdon, “Reel Song” ................................................. 2 by Jennifer Higdon Vivaldi, “Autumn” ...................................................... 2 Rimsky-Korsakov, “Flight of the Bumblebee” ......... 3 “Autumn,” III. Allegro Debussy, “Clair de Lune” .......................................... 3 from The Four Seasons Variego, Songs in Light: Firefly Music ...................... 4 by Antonio Vivaldi Joplin, The Entertainer .............................................. 4 “Flight of the Bumblebee” Crowe, How Birds Came Into the World .................. 5 from The Tale of Tsar Saltan Traditional/Arr. Robertson and Coolidge, by Rimsky-Korsakov Cherokee Morning Song ...................................... 5 “Clair de Lune” from Bergamasque Bryant & Bryant, Rocky Top ...................................... 6 by Claude Debussy Online Audio Link ............................................................ 6 Songs in Light: Firely Music by Jorge Variego Lessons: Cherokee Morning Song/ Moon Observation... .................................................. 7-13 Program repertoire and artists subject to change The Entertainer by Scott Joplin Activities & Resources for Teachers/ Audience Job Description ............................................ -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Gypsum in California

TN 2.4 C3 A3 i<o3 HK STATE OP CAlIFOa!lTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES msmtBmmmmmmmmmaam GYPSUM IN CALIFORNIA BULLETIN 163 1952 aou DIVl^ON OF MNES fZBar SDODSia sxh lasncisco ^"^^^^^nBM^^MMa^HBi«iaMa«NnMaMHBaaHB^HaHaa^^HHMi«nfl^HaMHiBHHHMauuHJin««aHiav^aMaHHaHHB«auKaiaMi^^M«ni^Maai^iMMWi^iM^ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA DAVIS STATE OF CALIFORNIA EARL WARREN, Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES WARREN T. HANNUM, Director DIVISION OF MINES FERRY BUILDING, SAN FRANCISCO 11 OLAF P. JENKINS, Chief San Francisco BULLETIN 163 September 1952 GYPSUM IN CALIFORNIA By WILLIAM E. VER PLANCK LIBRARY UNTXERollY OF CAUFC^NIA DAVIS LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL To IIlS EXCELLKNCY, TlIK IIONORAHLE EauL AVaRREN Governor of the State of California Dear Sir: I have the lionor to transmit herewitli liuUetiii 163, Gyj)- sinn in California, prepared under tlie direetion of Ohif P. Jenkins, Chief of the Division of ]\Iines. Gypsum represents one of the important non- metallic mineral commodities of California. It serves particularly two of California's most important industries, aprieulture and construction. In Bulletin 163 the author, W. p]. Xev Phinek, a member of the staff of the Division of Mines, has prepared a comprehensive treatise cover- ing all phases of the subject : history of the industry, geologic occurrence and origin of tlie minoi-al, mining, i)rocessing and marketing of the com- modity. Specific g3'psum i)roperties Avere examined and mapped. The report is profusely illustrated by maps, charts and photographs. In the preparation of the report it was necessary for the author to make field investigations, laboratory and library studies, and to determine how the mineral is used in industry as Avell as how it occurs in nature and how it is mined. -

Why It Matters

A Matter Of Scale The Scale Of The Problem Contents Part One: The Scale Of The Problem Chapter 1: One Ten Millionth Of A Metre 4 Chapter 2: One Millionth Of A Metre 19 Chapter 3: One Thousandth Of A Metre 31 Chapter 4: One Hundredth Of A Metre 44 Chapter 5: One Metre 55 Chapter 6: One Hundred Metres 70 Chapter 7: Beneath And Beyond 82 Part Two: Why It Matters Chapter 8: What Are We? 89 Chapter 9: Who Are We? 102 Chapter 10: Why Does It Matter? 115 Part Three: Making The Connection Chapter 11: Why Connect? 135 Chapter 12: How To Connect 148 Chapter 13: Why Can’t We Connect? 157 Part Four: How To Survive Chapter 14: Getting Angry 188 Chapter 15: You Are The System 197 Chapter 16: Making The Change 210 Chapter 17: Being Ourselves 253 Notes and References 264 2 Part One The Scale Of The Problem “Oh, the world is so big, and we are so small, The world is so big, are we here at all?” (Big Dipper, Songs From The Blue House) “The only constant I am sure of, Is this accelerating rate of change.” (Peter Gabriel, Downside-Up) A Matter Of Scale The Scale Of The Problem Chapter 1 One Ten Millionth Of A Metre Breathe in, and your body starts a battle. Countless microorganisms hitch a lift on every stream of air being pulled into your lungs, seeking out a place where they can embed themselves and multiply. Once inside every potential form of nutrition is fair game: blood cells, fat cells, skin, bone marrow, lymphatic fluid – all hosts for the army of invaders that just want to find a way of increasing their numbers. -

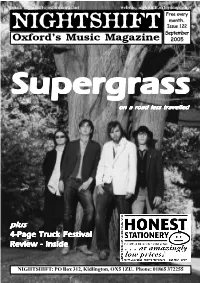

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 122 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SupergrassSupergrassSupergrass on a road less travelled plus 4-Page Truck Festival Review - inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE YOUNG KNIVES won You Now’, ‘Water and Wine’ and themselves a coveted slot at V ‘Gravity Flow’. In addition, the CD Festival last month after being comes with a bonus DVD which picked by Channel 4 and Virgin features a documentary following Mobile from over 1,000 new bands Mark over the past two years as he to open the festival on the Channel recorded the album, plus alternative 4 stage, alongside The Chemical versions of some tracks. Brothers, Doves, Kaiser Chiefs and The Magic Numbers. Their set was THE DOWNLOAD appears to have then broadcast by Channel 4. been given an indefinite extended Meanwhile, the band are currently in run by the BBC. The local music the studio with producer Andy Gill, show, which is broadcast on BBC recording their new single, ‘The Radio Oxford 95.2fm every Saturday THE MAGIC NUMBERS return to Oxford in November, leading an Decision’, due for release on from 6-7pm, has had a rolling impressive list of big name acts coming to town in the next few months. Transgressive in November. The monthly extension running through After their triumphant Truck Festival headline set last month, The Magic th Knives have also signed a publishing the summer, and with the positive Numbers (pictured) play at Brookes University on Tuesday 11 October.