Understanding the Tamil-Malayali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 29.05.2016 to 04.06.2016

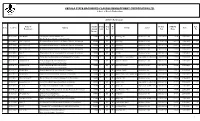

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 29.05.2016 to 04.06.2016 Name of the Name of Name of the Place at Date & Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police Arresting father of Address of Accused which Time of which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Officer, Rank Accused Arrested Arrest accused & Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Poonjar Cr.793/16, M B Kunnepparampil u/s 283 IPC Sreekumar, 35, House, Pattimattom 31.05.16, 1 Rasli K K Kasim Erattupetta Addl. SI of Police bail Male Kara, koovappally 11.00 hrs Police, Village. Erattupetta Vadakkekkar Cr.798/16, V M Jacob, Puthenkandathil 41, a 02.06.16, u/s 118(e) of Addl. SI of 2 Sabu Sais Attavi House, Nadackal, Erattupetta Police bail Male 19.30 hrs KP Act & 185 Police, Erattupetta of MV Act Erattupetta. Mylamannil House, Kurickal Cr.799/16, M B Moonkalar Estate Nagar u/s 118(a)) of Sreekumar, 50, 02.06.16, 3 Ayyappan Kutty Gopalan KP Act Erattupetta Addl. SI of Police bail Male 22.00 hrs Police, Erattupetta Kaduvamuzhy Cr.802/16, M R Saji, Addl. Prabhakaran 44, Vallippala House, 03.06.16, u/s 118(e) of SI of Police, 4 Manoj V.J Erattupetta Police bail Nair Male Moonnilavu Village. 17.00 hrs KP Act & 185 Erattyupetta of MV Act Puthiyathukunnel Cr.807/16, M R Saji, Addl. 42, Houase, 04.06.16, u/s 118(e) of SI of Police, 5 Siby Raghavan Erattupetta Police bail Male Panachippara, 17.15 hrs KP Act & 185 Erattyupetta of MV Act Poonjar Mattaackadu Cr.808/16, M R Saji, Addl. -

2015-16 Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2015-16 Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010113918 Anil Kumar Chathiyodu Thadatharikathu Jose 24000 C M R Tailoring Unit Business Sector $84,210.53 71579 22/05/2015 2 Bhavan,Kattacode,Kattacode,Trivandrum 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $52,631.58 44737 18/06/2015 6 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $157,894.74 134211 22/08/2015 7 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $109,473.68 93053 22/08/2015 8 010114661 Biju P Thottumkara Veedu,Valamoozhi,Panayamuttom,Trivandrum 36000 C M R Welding Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 13/05/2015 2 010114682 Reji L Nithin Bhavan,Karimkunnam,Paruthupally,Trivandrum 24000 C F R Bee Culture (Api Culture) Agriculture & Allied Sector $52,631.58 44737 07/05/2015 2 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 22/05/2015 2 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 25/08/2015 3 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114747 Pushpa Bhai Ranjith Bhavan,Irinchal,Aryanad,Trivandrum -

Migration and Social History of Anjunadu: Lessons from the Past for Sustainable Development – an Applied Study

PESQUISA – Vol.3, Issue-2, May 2018 ISSN-2455-0736 (Print) www.pesquisaonline.net ISSN-2456-4052 (Online) Migration and Social History of Anjunadu: Lessons from the Past for Sustainable Development – An Applied Study Santhosh George Assistant Professor, Dept. of History, Pavanatma College, Murickassery Email: [email protected] Article History ABSTRACT Received: At the north east portion of Idukki district of Kerala there are a few locations that 30 March 2018 shows extreme geographical differences compared to the rest of the district. These Received in revised locations include places namely Marayoor, Kanthalloor, Keezhanthoor and Karayoor form: 5 May 2018 and Kottagudi - collectively known as the „Anjunadu‟ (Five places). We can Accepted: experience a replication of Tamil culture on the valleys of this region. These gifted 16 May 2018 places are the abode of natural serenity, cluster of tribal settlements, a treasure of historical knowledge, a land of social formations and a can of cultural blending. KEY WORDS: Through this study the researcher tried to connect past and present for the future of the Anjunadu, Anjunadus. Basic historical courses of this region are tried to be analyzed in order to Responsible prepare a comprehensive outline for the sustainable development of this region. Hence Tourism, Migration, practicability has given more importance. Cultural fusion INTRODUCTION The Anjunadu: the land of Mesolithic and Neolithic life in the present Idukki district of Kerala state. This is the area from where an early image of the prehistoric men reveals. The petrogrphs , dolmens and petrolyph survive in this area gives us an idea to reconstruct the glorious social history of the valleys. -

Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (Scsp) 2014-15

Government of Kerala SCHEDULED CASTE SUB PLAN (SCSP) 2014-15 M iiF P A DC D14980 Directorate of Scheduled Caste Development Department Thiruvananthapuram April 2014 Planng^ , noD- documentation CONTENTS Page No; 1 Preface 3 2 Introduction 4 3 Budget Estimates 2014-15 5 4 Schemes of Scheduled Caste Development Department 10 5 Schemes implementing through Public Works Department 17 6 Schemes implementing through Local Bodies 18 . 7 Schemes implementing through Rural Development 19 Department 8 Special Central Assistance to Scheduled C ^te Sub Plan 20 9 100% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 21 10 50% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 24 11 Budget Speech 2014-15 26 12 Governor’s Address 2014-15 27 13 SCP Allocation to Local Bodies - District-wise 28 14 Thiruvananthapuram 29 15 Kollam 31 16 Pathanamthitta 33 17 Alappuzha 35 18 Kottayam 37 19 Idukki 39 20 Emakulam 41 21 Thrissur 44 22 Palakkad 47 23 Malappuram 50 24 Kozhikode 53 25 Wayanad 55 24 Kaimur 56 25 Kasaragod 58 26 Scheduled Caste Development Directorate 60 27 District SC development Offices 61 PREFACE The Planning Commission had approved the State Plan of Kerala for an outlay of Rs. 20,000.00 Crore for the year 2014-15. From the total State Plan, an outlay of Rs 1962.00 Crore has been earmarked for Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP), which is in proportion to the percentage of Scheduled Castes to the total population of the State. As we all know, the Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP) is aimed at (a) Economic development through beneficiary oriented programs for raising their income and creating assets; (b) Schemes for infrastructure development through provision of drinking water supply, link roads, house-sites, housing etc. -

List of Offices Under the Department of Registration

1 List of Offices under the Department of Registration District in Name& Location of Telephone Sl No which Office Address for Communication Designated Officer Office Number located 0471- O/o Inspector General of Registration, 1 IGR office Trivandrum Administrative officer 2472110/247211 Vanchiyoor, Tvpm 8/2474782 District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 2 (GL)Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471868 Thiruvananthapuram-695023 General Thiruvananthapuram District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 3 (Audit) Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471869 Thiruvananthapuram-695024 Audit Thiruvananthapuram Amaravila P.O , Thiruvananthapuram 4 Amaravila Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2234399 Pin -695122 Near Post Office, Aryanad P.O., 5 Aryanadu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0472-2851940 Thiruvananthapuram Kacherry Jn., Attingal P.O. , 6 Attingal Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2623320 Thiruvananthapuram- 695101 Thenpamuttam,BalaramapuramP.O., 7 Balaramapuram Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2403022 Thiruvananthapuram Near Killippalam Bridge, Karamana 8 Chalai Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2345473 P.O. Thiruvananthapuram -695002 Chirayinkil P.O., Thiruvananthapuram - 9 Chirayinkeezhu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2645060 695304 Kadakkavoor, Thiruvananthapuram - 10 Kadakkavoor Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2658570 695306 11 Kallara Trivandrum Kallara, Thiruvananthapuram -695608 Sub Registrar 0472-2860140 Kanjiramkulam P.O., 12 Kanjiramkulam Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2264143 Thiruvananthapuram- 695524 Kanyakulangara,Vembayam P.O. 13 -

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

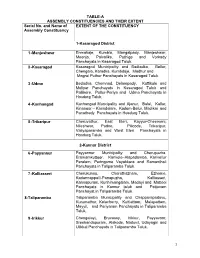

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Kattappana School Code Sub District Name of School School Type 30001 Munnar G

Kattappana School Code Sub District Name of School School Type 30001 Munnar G. V. H. S. S. Munnar G 30002 Munnar G. H. S. Sothuparai G 30003 Munnar G. H. S. S. Vaguvurrai G 30005 Munnar G. H. S. Guderele G 30006 Munnar L. F. G. H. S . Munnar A 30007 Munnar K. E. H. S . Vattavada A 30008 Munnar G. H. S. S. Devikulam G 30009 Munnar G. H. S. S. Marayoor G 30010 Munnar S. H. H. S. Kanthalloor A 30011 Peermade St. George`s High School Mukkulam A 30012 Nedumkandam Govt. H.S.S. Kallar G 30013 Nedumkandam S.H.H.S. Ramakalmettu A 30014 Nedumkandam C.R.H.S. Valiyathovala A 30015 Nedumkandam G.H.S. Ezhukumvayal G 30016 Kattappana M.M.H.S. Nariyampara A 30017 Peermade St.Joseph`s H.S.S Peruvanthanam A 30018 Peermade G.H.S.Kanayankavayal G 30019 Peermade St.Mary`s H.S.S Vellaramkunu A 30020 Kattappana SGHSS Kattappana A 30021 Kattappana OSSANAM ENG MED HSS KATTAPPANA U 30022 Peermade Govt V.H.S.S. T.T. I. Kumaly G 30023 Nedumkandam N S P High School Vandanmedu A 30024 Nedumkandam S.A.H.S. Vandanmedu A 30025 Peermade C.P.M. G.H.S.S. Peermedu G 30026 Peermade M.E.M.H.S.S. Peermede U 30027 Peermade Panchayat H.S.S. Elappara A 30028 Peermade G.H.S.Vagamon G 30029 Peermade St. Sebastians H.S.S. Cheenthalar A 30030 Peermade Panchayat H.S.S. Vandiperiyar A 30031 Nedumkandam Govt. H S S And V H S S Rajakumary G 30032 Peermade St. -

District Statistical Hand Book Idukki

GOVERNMENT OF KERALA DISTRICT STATISTICAL HAND BOOK IDUKKI DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS & STATISTICS THIRUVANANTHAPURAM-1990 GOVERWMEWr Of KERALA ** *** ** * VrSTRJCr STATISTICAi HA^IV BOOK r V U K K I » «« *** »«*« ««• «» * VEPAKTMEKT Or ECONOmCS AHV STATISTICS TRIl/AWPRaM - 1989 M V E P A D C D05308 National Systems Untt, National Institute of EducationtJ Plonnir J Aministration i do Marg.NewDeliii-llOOl^ DOC. ___ Date..............—J.8 Lv P R e F A C E Govz^nmznt KtKoia havz aifitddy dzcid^d to con&idzn. dUitfildt and even d&\fe-lopme.¥Vt bloc.k oa b<ulc un-itt to plan and zxnaitz 4e£ec^erf 4c/iemc4. Since. dl£i?.ftznt dzpan.tme.nt6 a^e fie.qalfLZd to undzfitake. de.tailzd planning zx.zkcaj>z , it ie> imponXant that thzy kavz to be pfiovidzd with, adtqaatz and tXmzly data at diAtfiict and block -deve^-4. The. dzpa^tmtnt ho6 KzczntZy pabliiiktd * Block Lav&l Statistics* ail thz 14 di4tA.icX4. *Vi&tfiict Statiitickl Hand Books' aKZ intzndzd to pfie.se.nt almost all impofiiant data dzpictinq th& socio'-zconomic conditions o^ the. distfiicZ, The VistKict StatisticaZ Hand Book Idukki u x l s p^epafLCd by Smt. K. Santha Kuma^i, Resza^ch O^^-ice^ unde^ the guidance o^ ShAi, P,K. Vidyanandan, Vistfiict Oi^icefL and Shfii. A M , Ha^ida^an fJai^L, Ve.paty Vi^ectofi, District Oi^^ice, Economics and Statistics, Idukki, The eamest z^^onts o^ Skfii, P,l/. Sub^amonian Acha^y, Uese.aKch Assistant and Sh^i, Vominic Paul, In-oe^tiQotofi o^ the VistKict Oi^icz in collecting and compiling the data a^c specially acknoi^Jledgzd in this context, I hope that this publication i^ill be o{ con^ideKable use to planners and KtseafichtKS who aKe intzfizsted to study thz p^oblejns ojj the district. -

Munnar Landscape Project Kerala

MUNNAR LANDSCAPE PROJECT KERALA FIRST YEAR PROGRESS REPORT (DECEMBER 6, 2018 TO DECEMBER 6, 2019) SUBMITTED TO UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME INDIA Principal Investigator Dr. S. C. Joshi IFS (Retd.) KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD KOWDIAR P.O., THIRUVANANTHAPURAM - 695 003 HRML Project First Year Report- 1 CONTENTS 1. Acronyms 3 2. Executive Summary 5 3.Technical details 7 4. Introduction 8 5. PROJECT 1: 12 Documentation and compilation of existing information on various taxa (Flora and Fauna), and identification of critical gaps in knowledge in the GEF-Munnar landscape project area 5.1. Aim 12 5.2. Objectives 12 5.3. Methodology 13 5.4. Detailed Progress Report 14 a.Documentation of floristic diversity b.Documentation of faunistic diversity c.Commercially traded bio-resources 5.5. Conclusion 23 List of Tables 25 Table 1. Algal diversity in the HRML study area, Kerala Table 2. Lichen diversity in the HRML study area, Kerala Table 3. Bryophytes from the HRML study area, Kerala Table 4. Check list of medicinal plants in the HRML study area, Kerala Table 5. List of wild edible fruits in the HRML study area, Kerala Table 6. List of selected tradable bio-resources HRML study area, Kerala Table 7. Summary of progress report of the work status References 84 6. PROJECT 2: 85 6.1. Aim 85 6.2. Objectives 85 6.3. Methodology 86 6.4. Detailed Progress Report 87 HRML Project First Year Report- 2 6.4.1. Review of historical and cultural process and agents that induced change on the landscape 6.4.2. Documentation of Developmental history in Production sector 6.5. -

Viswasa Pariseelana Kalolsavam 2019 20 Cherpunkal Diocese Result 10/09/2019 PALAI

Viswasa Pariseelana Kalolsavam 2019_20 Cherpunkal Diocese Result 10/09/2019 PALAI Page 1 Item 1 COLOURING INFANT All 1 Position Rank Grade Reg.No. Name S 1AFirst 783 MARIYA THOMAS 25/07/10 Points 5 5 VALAYATHIL CATHEDRAL PALA 2ASecond 614 LIZLIN SHIBU 30/06/10 Points 3 5 MYLADOOR ARAKULAM OLD MOOLAMATTOM 3AThird 665 ANGEL MARIA RENNY 13/07/10 Points 1 5 KOTAMPANANIYIL ST.AUGUSTINE SUNDY SCHOOL RAMAPURAM RAMAPURAM 4A=/= 438 ALEENA JOMON 22/02/10 Points 0 5 VARAPADAVIL ST.JOHN THE BAPTIST SUNDAY SCHOOL KADUTHURUTHY 5A=/= 797 ALDRINA SANTHOSH 19/04/10 Points 0 5 MANIANGATTU LALAM OLD PALA 6A=/= 751 ANN MARIA BINOY 10/12/10 Points 0 5 PALACKAL TEEKOY TEEKOY 7B=/= 707 AJAS 02/02/11 Points 0 3 KOLLAMPARAMBIL CHRISTHURAJ SUNDAY SCHOOL KAYY PRAVITHANAM 8B=/= 234 ALONA SANTHOSH 06/01/10 Points 0 3 NELLIKUZHIYIL MARYLAND THUDANGANAD 9B=/= 413 JOSEPH JOSHY 10/05/12 Points 0 3 THAZHATHUVEETIL ST.AUGUSTINES, KADANAD KADANAD 9B=/= 495 ALPHONSA GEORGE 13/01/11 Points 0 3 PUTHIYAKUNNEL ST.GEORGE FORANE SUNDAY SCHOOL, KOOTTICKAL KOOTTICKAL 9B=/= 694 DIYA GEO 09/03/10 Points 0 3 PLATHOTTATHIL ELAMTHOTTAM PRAVITHANAM 10=/= B 331 KURIAN BIJU 11/04/10 Points 0 3 PADINJAREMURIYIL LITTLE FLOWER SUNDAY SCHOOL CHEMPILAVU CHERPUMKAL 11=/= B 408 ANUJA MARY SURESH 13/01/12 Points 0 3 THATTAMPARAMBIL ST MARY'S SUNDAY SCHOOL, MANATHOOR KADANAD Viswasa Pariseelana Kalolsavam 2019_20 Cherpunkal Diocese Result 10/09/2019 PALAI Page 2 11=/= B 490 DENNA ROSE 08/02/10 Points 0 3 PEZHATHUMMOOTTIL NIRMALA SUNDANDAY SCHOOL YENDAYAR KOOTTICKAL 12=/= B 192 DIYA THERESE MANOJ 10/12/10 Points 0 3 CHIRAYATH ST. -

Landslide Vulnerability Assessment in Devikulam Taluk, Idukki District, Kerala Using Gis and Machine Learning Algorithms

Landslide Vulnerability Assessment in Devikulam Taluk, Idukki District, Kerala Using Gis and Machine Learning Algorithms Bhargavi Gururajan ( [email protected] ) SRMIST: SRM Institute of Science and Technology Arun nehru Jawaharlal SRMIST: SRM Institute of Science and Technology Research Article Keywords: Landslide, geographical hazard, Matthews correlation ecient (MCE), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) Posted Date: June 14th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-487079/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/14 Abstract Landslide is a chronic problem that causes severe geographical hazard due to development activities and exploitation of the hilly region and it occurs due to heavy and prolongs rain ow in the mountainous area. Initially, a total of 726 locations were identied at devikulam taluk, Idukki district (India). These landslide potential points utilised to construct a spatial database. Then, the geo spatial database is then split randomly into 70% for training the models and 30% for the model validation. This work considers Seven landslide triggering factors for landslide susceptibility mapping. The susceptibility maps were veried using various evaluation metrics. The metrics are sensitivity, specicity, accuracy, precision, Recall, Matthews correlation ecient (MCE), Area Under the Curve (AUC), Kappa statistics, Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Square Error (MSE).The proposed work with 5 advanced machine learning approaches assess the landslide vulnerability.It includes Logistic Regression (LR), K Nearest Neighbor (KNN), Decision tree classier, Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) and Gaussian Naïve Bayes modelling and comparing their performance for the spatial forecast of landslide possibilities in the Devikulam taluk. -

Poonjar Assembly Kerala Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/KR-101-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5313-597-3 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 130 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) at a Glance | Features of Assembly 1-2 as per Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) in 2 District | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary 3-9 Constituency -(Lok Sabha) | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-11 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages