THE DEVELOPMENT of P.K. PAGE's IMAGERY: the SUBJECTIVE EYE—THE EYE of the CONJUROR by ALLEN KEITH VALLEAU B. Comm., University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poetry and Prose of Pk Page

THE POETRY AND PROSE OF P. K. PAGE: A STUDY IN CONFLICT OF OPPOSITES by JILL I. TOLL FARRUGIA B. A., Queen's University, 1963 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1971 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada CONTENTS Chapter Page I. CONFLICT OF OPPOSITES 1 II. CONFLICT OF SOLITUDE WITH MULTITUDE 14 III. CONFLICT OF RESTRAINT WITH FREEDOM ..>... 60 IV. IMAGISTIC CONFLICT OF STONE AND FLOWER .... 84 V. CONFLICT OF SUBJECTIVITY OF PERCEPTION WITH POETIC OBJECTIVITY 94 WORKS CITED 107 Patricia K. Page's prose and poetry exhibit a dynamic creative tension resulting from the conflict of opposites in theme and imagery patterns and in the poet's attitude and perception of her subjects. The concept of separateness results from the thematic oppo• sition of forces of solitude and multitude which focus on the despair of the isolated individual unable to emerge from his 'frozen' cave-like existence and to attain a community of shared feeling. -

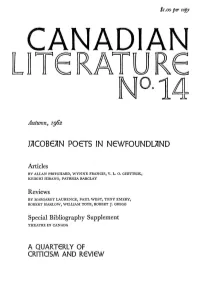

Jacobean P06ts in Newfoundland

$i.oo per copy Autumn, ig62 JACOBEAN P06TS IN NEWFOUNDLAND Articles BY ALLAN PRITCHARD, WYNNE FRANCIS, V. L. 1 , 1 HIRANO, PATRICIA BARCLAY Reviews BY MARGARET LAU R E N C E, P AU L WEST, TONY EMERY, ROBERT HARLOW, WILLIAM TO YE , ROBERT J. GREGG Special Bibliography Supplement THEATRE IN CANADA A QUARTERLY OF CRITICISM AND R6VI6W CAUTIOUS INEVITABILITY PROFESSOR DESMOND PACEY has rendered many services to writing in Canada, and particularly as the only considerable historian of literature in English-speaking Canada. To these we can now add another service, less sub- stantial, but no less satisfying in its own way — that of persuading the Times Literary Supplement to admit, after having implicitly denied it twelve years ago, that something which can be called a "Canadian literature" has at last come into being. The new edition of Professor Pacey's Creative Writing in Canada — recently released in England — was the subject not merely of a review, but of an editorial in the TLS which has some salutary things to say about both the character of Canadians and that character's relation to their literary productions. No one need mistake a Canadian for other than what he is; and if "character" is given a more particular interpretation, the Canadian is as resolute as any other national in asserting his identity, in the face of considerable odds. England on the one hand and the United States on the other are set to lure him off his inde- pendent track. But whether it is that the caution needed for such a difficult navi- gation spoils with self-consciousness the free expression of his identity, or that his character in its realization on a national scale does not insist upon being imagi- natively interpreted, it is certain that he has fallen behind other Commonwealth countries in arousing curiosity abroad and establishing a sympathetic image. -

Reading the Field of Canadian Poetry in the Era of Modernity: the Ryerson Poetry Chap-Book Series, 1925-1962

READING THE FIELD OF CANADIAN POETRY IN THE ERA OF MODERNITY: THE RYERSON POETRY CHAP-BOOK SERIES, 1925-1962 by Gillian Dunks B.A. (With Distinction), Kwantlen Polytechnic University, 2011 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2013 © Gillian Dunks, 2013 ii Abstract From 1925 to 1962, the Ryerson Press published 200 short, artisanally printed books of poetry by emerging and established Canadian authors. Series editor Lorne Pierce introduced the series alongside other nationalistic projects in the 1920s in order to foster the development of an avowedly Canadian literature. Pierce initially included established Confederation poets in the series, such as Charles G.D. Roberts, and popular late-romantic poets Marjorie Pickthall and Audrey Alexandra Brown. In response to shifting literary trends in the 1940s, Pierce also included the work of modernists such as Anne Marriott, Louis Dudek, and Al Purdy. Following Pierre Bourdieu, I read the Ryerson series as a sub-field of literary production that encapsulates broader trends in the Canadian literary field in the first half of the twentieth century. The struggle between late-romantic and modernist producers to determine literary legitimacy within the series constitutes the history of the field in this period. Pierce’s decision to orient the series towards modernist innovation during the Second World War was due to late romantics’ loss of their dominant cultural position as a result of shifting literary tastes. Modernist poets gained high cultural capital in both the Ryerson series and the broader field of Canadian literary production because of their appeal to an audience of male academics whose approval ensured their legitimacy. -

![Anglo-Canadian Modernists in Transit[Ion]: Collectivity and Identity in Mid-Century Canadian Modernist Travel Writing](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6016/anglo-canadian-modernists-in-transit-ion-collectivity-and-identity-in-mid-century-canadian-modernist-travel-writing-3426016.webp)

Anglo-Canadian Modernists in Transit[Ion]: Collectivity and Identity in Mid-Century Canadian Modernist Travel Writing

Anglo-Canadian Modernists in Transit[ion]: Collectivity and Identity in Mid-Century Canadian Modernist Travel Writing by Emily Ballantyne Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia April 2019 © Copyright by Emily Ballantyne, 2019 Dedication I would like to dedicate this dissertation to my scholarly community, my friends from the early days of the Editing Modernism in Canada project. You showed me how to perse- vere and overcome with strength, courage, and dignity. I may not have had a PhD cohort, but I always had you. ii Table of Contents Dedication .................................................................................................................. ii Abstract ..................................................................................................................... v List of Abbreviations Used ......................................................................................... vi Acknowledgments .................................................................................................... vii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 1 COMMUNITY AND EXILE: AFFILIATION BEYOND THE NATION ......................................... 6 CANADIAN MODERNIST TRAVEL WITHIN CANADIAN MODERNIST STUDIES ................... 13 CANADIAN MODERNISTS AS TRAVEL/LING WRITERS ..................................................... 22 CHAPTER TWO: EXILE BEYOND RETURN: -

A Poet Past and Future

A POET PAST AND FUTURE Patrick Anderson 'Y JUNE 1971 I had been away from Canada for twenty- one years. For ten of these years I had been without my Canadian passport, and the little certificate which documented my citizenship and whose physical pos- session was one of the last acts of a despairing nostalgia; I had asked for it in Madrid and received it in Tangier. Of the two documents the passport was the more precious. It became the symbol of a fine transatlantic mobility; of dollars, supposing there were any; of a difference not easily defined; and it made me almost a tourist in the land of my birth. I had taken refuge in it on the one or two occasions when anti-British students ganged up on me in Athens. Once, in- deed, when I showed it to an inquisitive waitress in a bar she had expressed some disbelief, pointing (as it seemed to me) to something sad about my face, the hollows under my eyes, the growing wrinkles of middle-age, as though a person so world-weary was unlikely to belong to such a fresh and vigorous part of the world. The odd thing is that last summer, despite the above experience, I found my- self sitting at my work-table in rural Essex writing poems about Canada. F. R. Scott had just posted me a batch of papers left in his house since, I think, 1947; the batch was nowhere as big as I expected; much of it was any way poor stuff, strained, rhetorical, beset by what Thorn Gunn has called "the dull thunder of approximate words"; but there was an evocation of a lake-scene in the Eastern Townships which, with a great deal of revision, might just about do (it became the new "Memory of Lake Towns"). -

Montreal Poets of the Forties

MONTREAL POETS OF THE FORTIES Wynne Francis DURiNG THE WAR YEARS Stanley Street was the centre of Montreal's "little bohemia". In the section of Stanley between Sherbrooke and St. Catherine Streets stood a row of disreputable old tenements. Cheap rooms, blind pigs, private gambling clubs, bookies and numerous other nefarious enter- prises thrived here. It used to be said that if you pushed the right buzzer and knew the password you could get anything illegal that you wanted at any time of day or night in that block. Shuttered and draped, the upper windows gave away no secrets. At street level shoe shine parlours, cheap restaurants, Jewish tailors and Chinese laundries crowded together, each blistering with bilingual signs. And up and down the sidewalk, catching soldiers and tourists like flies, strolled the girls, ignoring the complaints of the Y.M.C.A. authorities across the street. Painters and writers were to be found spotted through the tenements, in attics, in basements and in the back rooms of shops. The rent was cheap, the location central, the bookstores, art galleries and universities within walking distance. This setting provided the backdrop for the activities of the young writers and artists later called the "First Statement Group". The notorious location lent atmosphere to the public image of these writers as "Montreal's Bohemians"; and talent and poverty, brash youthfulness, vociferous belligerence, their dishevelled personal appearance and irregular living habits gave the description further credibility. The central figure, if not the leader, of the "First Statement Group" was John Sutherland. John came to Montreal from Saint John, New Brunswick, in 1941 21 MONTREAL POETS to attend McGill University after a three year bout with tuberculosis. -

Miriam Waddington Fonds MG31-D54 Container File File Title Date

Library and Archives Bibliothèque et archives Canada Canada Canadian Archives Direction des archives Branch canadiennes MIRIAM WADDINGTON FONDS MG31-D54 Finding Aid No. 1415 / Instrument de recherche no 1415 Prepared in 1983, revised in 1986 and 1991 Préparé en 1983, revisé en 1986 et 1991 par by Anne Goddard, in 1994 by Sarah Anne Goddard , 1994 par Sarah Montgomery Montgomery of the Social and Cultural des Archives sociales et culturelles et en Archives and in 2007-2008 by Janet Murray 2007-2008 par Janet Murray et Catherine and Catherine Hobbs of Literary Arts. Hobbs des Arts littéraires.. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS NOTEBOOKS, JOURNALS and NOTES SERIES ............................1, 86, 95 GENERAL MANUSCRIPTS FILES SERIES ..............................2, 25, 31, 89 POETRY MANUSCRIPTS SERIES ...............................8, 17, 18, 77, 89, 115 CRITICAL WORKS and EDITIONS SERIES............................10, 16, 90, 132 PERSONAL MATERIAL SERIES ..............14, 27, 29, 30, 35, 42, 86, 87, 128, 132, 134 PRINTED MATERIAL SERIES....................................15, 28, 44, 89, 130 GENERAL CORRESPONDENCE SERIES ..................................18, 29, 66 TRANSLATIONS SERIES.................................................79, 110 TEACHING MATERIAL SERIES........................................36, 88, 113 SUBJECT FILES SERIES............................................... 79, 90, 98 NOMINAL CORRESPONDENCE FILES SERIES ......................44, 65, 69, 90, 92 PERSONAL CORRESPONDENCE FILES SERIES .....................64, 65, 66, 89, 91 FAMILY -

Refraining Montreal Modernisms

Refraining Montreal Modernisms: A Biographical Study of Betty Sutherland and her Work with First Statement, First Statement Press, Contact, Contact Press, and CIV/n by Michele Rackham, B.A. (Honours) A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 21 September 2006 © copyright 2006, Michele Rackham Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-18293-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-18293-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

REVIEWS Re Making

110 REVIEWS Re Making Louis Dudek and Michael Gnarowski, eds. The Making of Modern Poetry in Canada: Essential Commentary on Poetry in English. Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 2017. xliii + 340pp. The implicit question to be answered by any book review is, “did it have to be published?” In the retrospect of fifty years, few works of scholarship will stand the interrogation. In the case of this reprinting of a 1967 compilation by Louis Dudek and Michael Gnarowski of “essential articles on contemporary Canadian poetry in English”—the original subtitle—the answer cannot be straightforward. The original publication was a milestone in the emergence of Canadian modernist criticism. Without it, progress in that field would have been slowed and differently apportioned. It needed to be published then, and the book needs to this day to be widely available to students of Canadian literature, although it is now itself a historical document rather than an innovative or even accurate accounting of our poetry’s documentary history. The problem is, it is widely available, in a large number of North American university libraries across Canada and the United States, and no doubt in hundreds of public libraries not as amenable to quick online survey. As the present re-release is only very slightly altered from the original publication, its chief merit will lie in its new availability as an e-book. While The Making deserves the new readers who might be drawn to that format, there is no work for the reviewer in noticing the mere fact. Instead, the time seems ripe for a retrospective comment on The Making in its original form, preserved intact here, and for brief reflection on new short texts by Michael Gnarowski and Collett Tracey serving to bookend in this re- release the preserved pages of the original Ryerson book. -

Editing Canadian Modernism Dean Irvine Dalhousie University

Editing Canadian Modernism Dean Irvine Dalhousie University I. Modernist Editions and Archives Modernist poetry in English Canada would not have a history without its editors. e history of modernism in Canada has largely been that of editors who were also poets and poets who were also editors. Given that so many American and British modernist authors were active in various capacities as editors, it follows that the conjuncture of poetic and editorial practice has long been recognized as a constitutive narrative of Anglo- American modernism (see Bornstein). Although Canada does not really have its own version of Pound editing e Waste Land, the correlation of authors and editors holds true for scholarship on Canadian modern- ists. e once-dominant critical archive devoted to what Brian Trehearne calls the “two Modernisms” (AestheticismAestheticism ) associated with successive generations of poets, editors, and literary magazines in Montreal in the s and s has, in recent years, undergone revision to include mul- tiple modernisms and little-magazine groups located in cities extending from Halifax to Victoria.¹ Because only a handful of modernist poets in Canada published book collections before the s, and because most For overviews of criticism concerning the Montreal modernists of the s and s, see Trehearne, Aestheticism and “Critical.” For a recent study of the wider dispersion of modernist little-magazine communities in Canada, see Irvine. ESC .–.– (March/June(March/June ):): –– relied on little magazines to serve as outlets for their -

Ralph Gustafson Literary Papers at the University of Saskatchewan

Ralph Gustafson A Finding Aid for the Ralph Gustafson Literary Papers at the University of Saskatchewan, Prepared by Joel Salt Special Collections Supervisor University of Saskatchewan February 2010 Collection Summary: Title: Ralph Gustafson Literary Papers. Dates: 1930s-late1960s. ID No.: MSS 6– . Creator: Gustafson, Ralph, 1909-1995. Extent: 8 boxes; 1m. Language: Collection material in English. Repository: Special Collections, University of Saskatchewan. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Abstract: The Gustafson collection includes five boxes of correspondence, including many with some of Canada's leading literary figures from the 1930s to the 1960s. The collection also houses manuscripts, proofs, and published first editions of some of Gustafson's well-known publications. There are also newspaper clippings and reviews. Provenance: The papers were acquired in the 1960s at a similar time to the acquisitions of the Layton and the Purdy collections. Custodial Note: Copyright info Biography: Ralph Gustafson (1909-1995) was born in Lime Ridge, Quebec, but grew up in Sherbrook. He attended Bishop's University, earning a double honours B.A. in English and History in 1929, winning the Governor General's Medal and placing top in his class. He received an M.A. in 1930, successfully defending his thesis "The Sensuous Imagery of Shelley and Keats." He also completed a B.A. at Keble College, Oxford in 1933, an M.A. in 1963, and was awarded a D. Litt. from Mount Allison in 1973, a D.C.L. from Bishop's University in 1977, and a D. Litt from York University in 1991. After his B.A. from Oxford, Gustafson moved to New York, where he stayed for many years and become friends with many of the members of the literary scene there, including Auden, Cummings and W.C. -

The Anthology of Canada's Gay Male Poets

SEMINAL THE ANTHOLOGY OF CANADA’S GAY MALE POETS edited by JOHN BARTON and BILLEH NICKERSON ARSENAL PULP PRESS Vancouver CONTENTS Introduction by John Barton · 7 Acknowledgements · 31 Note on the Text · 35 Frank Oliver Call · 39 Blaine Marchand · 213 Émile Nelligan · 41 Doug Wilson · 218 Robert Finch · 44 Sky Gilbert · 220 John Glassco · 52 Daniel David Moses · 224 Douglas LePan · 58 Ian Stephens · 228 Patrick Anderson · 68 Bill Richardson · 232 Brion Gysin · 79 David Bateman · 235 Robin Blaser · 85 John Barton · 238 David Watmough · 96 Jim Nason · 248 John Grube · 97 Dennis Denisoff · 253 Jean Basile · 99 Clint Burnham · 259 George Stanley · 101 Brian Day · 262 Daryl Hine · 111 Norm Sacuta · 266 Edward A. Lacey ·121 Ian Iqbal Rashid · 269 bill bissett · 132 Todd Bruce · 274 Michael Estok · 142 R. M. Vaughan · 279 Stan Persky · 147 Gregory Scofield · 284 Walter Borden · 151 Craig Poile · 293 Keith Garebian · 154 R. W. Gray · 297 Michael Lynch · 157 Andy Quan · 300 André Roy · 161 Brian Rigg · 304 Ian Young · 170 Michael V. Smith · 307 Jean-Paul Daoust · 179 Billeh Nickerson · 311 Stephen Schecter · 188 Shane Rhodes · 315 Richard Teleky · 192 Orville Lloyd Douglas · 319 H. Nigel Thomas · 197 Joel Gibb · 321 Gilles Devault · 200 Michael Knox · 323 Bertrand Lachance · 204 Sean Horlor · 325 Jean Chapdelaine Gagnon · 205 Contributors · 329 Permissions ·359 Index · 367 INTRODUCTION 7 “The homosexual poet,” according to Robert K. Martin, “often seeks poetic ‘fathers’ who in some sense offer a validation of Introduction his sexual nature. Whatever he may learn poetically from the great tradition, he cannot fail to notice that this tradition is, at least on the surface, almost exclusively heterosexual.”1 It is out of such a desire for affirmation, for exemplars and mentors, that the impulse to compile Seminal, the first historically comprehensive compendium of gay male poetry written by Canadians, first arose.