AJM Smith, John Sutherland, and Louis Dudek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poetry and Prose of Pk Page

THE POETRY AND PROSE OF P. K. PAGE: A STUDY IN CONFLICT OF OPPOSITES by JILL I. TOLL FARRUGIA B. A., Queen's University, 1963 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1971 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada CONTENTS Chapter Page I. CONFLICT OF OPPOSITES 1 II. CONFLICT OF SOLITUDE WITH MULTITUDE 14 III. CONFLICT OF RESTRAINT WITH FREEDOM ..>... 60 IV. IMAGISTIC CONFLICT OF STONE AND FLOWER .... 84 V. CONFLICT OF SUBJECTIVITY OF PERCEPTION WITH POETIC OBJECTIVITY 94 WORKS CITED 107 Patricia K. Page's prose and poetry exhibit a dynamic creative tension resulting from the conflict of opposites in theme and imagery patterns and in the poet's attitude and perception of her subjects. The concept of separateness results from the thematic oppo• sition of forces of solitude and multitude which focus on the despair of the isolated individual unable to emerge from his 'frozen' cave-like existence and to attain a community of shared feeling. -

A Voice of English-Montreal the First Twenty Years of Véhicule Press

A Voice of English-Montreal The First Twenty Years of Véhicule Press, 1973–1993 Amy Hemond Department of English McGill University, Montreal April 2019 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Amy Hemond 2019 Hemond ii Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................ iii Résumé ................................................................................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................... v Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................... 6 The Véhicule fonds .................................................................................................................................................. 13 The History of English-Quebec Publishing ............................................................................................................... 16 Discussion ................................................................................................................................................................ 26 Chapter 1: The Poetic Prelude to a Small Press, 1972–1976 ................................................................................ -

TREVOR CAROLAN / Dorothy Livesay in North Vancouver

TREVOR CAROLAN / Dorothy Livesay in North Vancouver Ten years ago, as a District of North Vancouver Councillor, I proposed to my colleagues in the nearby City of North Vancouver the idea of creating a memorial plaque in honour of Dorothy Livesay. An important twentieth century Canadian poet and social activist, Livesay lived in the city on and off for more than twenty years with her husband, fellow socialist Duncan McNair. They lived in several homes within view of the inner harbour: at Cumberland Crescent, then at 848-6th Street about a block from Sutherland High School, and later on toney Grand Boulevard. Livesay wrote some of her best work here making it an appropriate place to commemorate not only a fine poet, but also a champion of women's rights and family planning before either became fashionable. The idea of a memorial marker-stone failed to gain traction with the politicians of the day; it's an idea that's still out there for commissioning. In her memoir Journ ey with My Selves, Livesay says that she originally arrived in BC wanting to find her way to the San Francisco literary scene. In fact, she came to Vancouver to work as an editor for a communist labour journal. From Vancouver she hoped to travel further south to join the Depression-era's well-established leftist arts community concentrated in the San Francisco Bay Area. This was IWW territory and numerous publications there served the One Big Union labour ideal, which appealed to her political interests. The city also enjoyed a long liberal tradition in its journalism and politics. -

Selected Poems by Merle Amodeo

Canadian Studies. Language and Literature MARVIN ORBACH, MERLE AMODEO: CANADIAN POETS, UNIVERSAL POETS M.Sc. Miguel Ángel Olivé Iglesias. Associate Professor. University of Holguín, Cuba Abstract This paper aims at revealing universality in Marvin Orbach, an outstanding Canadian book collector and poet, and Merle Amodeo, an exquisite Canadian poet and writer. Orbach´s poems were taken from Redwing, book published by CCLA Hidden Brook Press, Canada in 2018; and Amodeo´s poems from her book After Love, Library of Congress, USA, 2014. Thus, the paper unveils for the general reader the transcendental scope of these two figures of Canadian culture. In view of the fact that they are able to recreate and memorialize their feelings and contexts where they live, and show their capacities to discern beyond the grid of nature, society and human experience, directly and masterfully exposing them, it can be safely stated that both Orbach and Amodeo reach that point where what is singular in them acquires universality, and in return what is universal crystallizes in their singularity. Key Words: universality, Orbach, Redwing, Amodeo, After Love Introduction My connection with universal poetry began during my college years. I enjoyed great English and American classics so much that I even memorized many of their poems. It proved very useful later in my professional career, as I would read excerpts from poems to my students in class. Canada, and Canadian poets, had less presence on the curricular map at the time. Fortunately, I had the chance to become acquainted with Canadian poetry through the Canada Cuba Literary Alliance (CCLA), founded by Richard and Kimberley Grove back in 2004. -

THE DEVELOPMENT of P.K. PAGE's IMAGERY: the SUBJECTIVE EYE—THE EYE of the CONJUROR by ALLEN KEITH VALLEAU B. Comm., University

THE DEVELOPMENT OF P.K. PAGE'S IMAGERY: THE SUBJECTIVE EYE—THE EYE OF THE CONJUROR by ALLEN KEITH VALLEAU B. Comm., University of British Columbia, 1969 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of ENGLISH We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA July, 1973. In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of English The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date July 14, 1973. i ABSTRACT In an attempt to develop a better perspective on P.K. Page's work, the thesis concentrates on the development of her imagery. The imagery illustrates the direction of Page's development and a close study of its nature will uncover the central concerns of Page's writing. The first chapter of the thesis examines the field of critical analysis already undertaken on Page showing its good points and its weak points. The following three chapters trace the chronological development of Page's work. The second chapter covers up to the writing of The Sun And The Moon in 1944. -

Notes on Contributors

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Calgary Journal Hosting Notes on Contributors MARGARET ATWOOD was born in Ottawa in 1939 and received de• grees from the University of Toronto and Harvard University. She has taught at a number of Canadian universities and last year was Writer in Residence at the University of Toronto. She won the Governor-General's Award in 1966. Her five books of poems include The Circle Game (1966), The Journals of Susanna Moodie (1970) and Power Politics (1971). She has also written two novels, The Edible Woman (1969), and Surfacing (1972) and a critical book Survival (1972). DOUGLAS BARBOUR lives and works in Edmonton, Alberta. He has four books of postry out, of which the latest is songbook (talon- books, 19731. The others are Land Fall (1971), A Poem as Long as the Highway (1971), and White (1972). S. A. DJWA, Associate Professor, teaches Canadian Literature at Simon Fraser University and is a regular contributor to Cana• dian Literature and the Journal of Canadian Fiction. Professor Djwa has recently completed a book on E. J. Pratt (Copp Clark and McGill-Queen's University Press) and has developed com• puter concordances to fourteen Canadian poets in the prepara• tion of a thematic history of English Canadian poetry. She is now working on an edition of Charles Heavysege's poetry for the University of Toronto Press Literature of Canada Reprint Series. RALPH GUSTAFSON'S eighth book of poems, Fire on Stone, will be published by McClelland & Stewart, Toronto, autumn 1974. -

The Poetry of Raymond Souster and Margaret Avison

THE POETRY OF RAYMOND SOUSTER AND MARGARET AVISON by Francis Mansbridge Thesis presented to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in English literature UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA OTTAWA, CANADA, 1975 dge, Ottawa, Canada, 1975 UMI Number: DC53320 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform DC53320 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 TABLE OP CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER I. POETIC ROOTS OP MARGARET AVISON AND RAYMOND SOUSTER 8 CHAPTER II. CRITICAL VIEWS ON AVISON AND SOUSTER . 46 CHAPTER III. MARGARET AVISON 67 CHAPTER IV. RAYMOND SOUSTER 154 CHAPTER V. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 225 BIBLIOGRAPHY 241 LIST OP ABBREVIATIONS BCP The Book of Canadian Poetry, ed. by A.J.M. Smith CT The Colour of the Times D The Dumbfounding PM Place of Meeting PMC Poetry of Mid-Century, ed. by Milton Wilson SF So Par So Good SP 1956 Selected Poems (1956 edition) SP 1972 Selected Poems (1972 edition) TE Ten Elephants on Yonge Street WS Winter Sun Y The Years 111 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Special thanks to Raymond Souster for his generous hospi tality on my trips to Toronto, and his interest and perceptive comnusnts that opened up new perspectives on his work; to the Inter- Library Loan department of the University of Ottawa Library, whose never-failing dependability saved much time; and finally to my Directress, Dr. -

"I "In Miriam Waddington's Poetry

TRANSITIONAL SPACES: CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MODERNIST “I” IN MIRIAM WADDINGTON’S POETRY Esther Sánchez-Pardo González Universidad Complutense de Madrid ABSTRACT In her first books of poetry (Green World, The Second Silence), Miriam Waddington explores female identity and subjectivity from the perspective of what she refers to in her poem “The Bond” as the “Jewish me.” In these two books, one finds “the credibility of colloquial speech as an alternative to impersonal modernism” (Arnason). My paper is an attempt to approach the construction of the lyric “I” exploring the dialectic between inner and outer world —a transitional space where the subject engages in a process of transformation. In Waddington’s poetry the modernist lyric was a central means to explore a rupture with the old world (colonial and patriarchal) in her own textual terms. KEY WORDS: Miriam Waddington, Modernism, lyric poetry, jewishness, women. RESUMEN En sus dos primeros poemarios (Green World, The Second Silence), Miriam Waddington explora la identidad y subjetividad femeninas desde la perspectiva de lo que en su poema 169 “The Bond” llama el “yo judío”. En estos dos volúmenes encontramos “la credibilidad de la lengua coloquial como alternativa a la impersonalidad modernista” (Arnason). Este ensayo es una aproximación a la construcción del “yo” lírico en este período, que explora la dialéc- tica entre mundo interior y exterior —un espacio transicional donde el sujeto experimenta un proceso de transformación. En la poesía de Waddington, la lírica modernista fue sin duda el medio privilegiado para explorar la ruptura con el viejo mundo (colonial y patriar- cal) de acuerdo a su singular manera de entender el texto poético. -

Miriam Waddington, the Collected Poems of Miriam Waddington. Edit- Ed with an Introduction by Ruth Panofsky

Canadian Jewish Studies / Études juives canadiennes, vol. 23, 2015 165 Miriam Waddington, The Collected Poems of Miriam Waddington. Edit- ed with an introduction by Ruth Panofsky. 2 Volumes. (Ottawa: Univer- sity of Ottawa Press, 2014), 1109 pages. These two beautifully published and scrupulously edited volumes represent the first time that all of Miriam Waddington’s verse has been collected in one edition. Wad- dington was one of the major Canadian poets of the middle decades of the twentieth century. She wrote short stories and essays in addition to poetry, but it is as a poet that she made her mark. She was remarkably prolific, publishing 14 books of verse during her lifetime, not to mention numerous uncollected poems in a variety of journals. In these two volumes, published under the aegis of Editions of Modernism in Canada and edited with an introduction by Ruth Panofsky, Professor of English at Ryerson University, we finally get a comprehensive critical and scholarly edition of all of Waddington’s published poetry, as well as a selection of her uncollected and unpublished poems. The second volume also contains examples of Waddington’s translations from Yiddish, German and Russian into English, a welcome inclusion, since these translations testify not only to Waddington’s skill as a poet, but also as a translator, and they provide a testament to the wide scope of her literary interests. In her excellent introduction, Panofsky contends that Waddington’s career as a modernist has not been sufficiently studied. Despite, or perhaps because of, being a contemporary of Louis Dudek, A. M. -

Uvic Thesis Template

Serious Play: Alden Nowlan, Leo Ferrari, Gwendolyn MacEwen, and their Flat Earth Society by David Eso B.A., University of British Columbia, 2004 M.A., University of Calgary, 2015 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English © David Eso, 2021 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This Dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Serious Play: Alden Nowlan, Leo Ferrari, Gwendolyn MacEwen, and their Flat Earth Society by David Eso B.A., University of British Columbia, 2004 M.A., University of Calgary, 2015 Supervisory Committee Iain Higgins, English Supervisor Eric Miller, English Departmental Member Heather Dean, UVic Libraries Outside Member Neil Besner, University of Winnipeg Additional Member iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the satirical Flat Earth Society (FES) founded at Fredericton, New Brunswick in November 1970. The essay’s successive chapters examine the lives and literary works of three understudied authors who held leadership positions in this critically unserious, fringe society: FES Symposiarch Alden Nowlan; the Society’s President Leo Ferrari; and its First Vice-President Gwendolyn MacEwen. Therefore, my project constitutes an act of recovery and reconstruction, bringing to light cultural work and literary connections that have largely faded from view. Chapters show how certain literary writings by Nowlan, Ferrari, or MacEwen directly or indirectly relate to their involvement with FES, making the Society an important part of their cultural work rather than a mere entertainment, distraction, or hoax. -

Tnbr04de17.Pdf

IHE HOHEMaKBRg myths built around the idea of the prairie as a hostile environment whose flatness, emptiness and immensity have made psycological adaptation impossible. In two witty lines the poet dispels the mist of this negative vision of the prairie saying that: The chief difference in the land is that there is more of it. (*5) Then, as if to prove that the prairie is neither empty nor frightening she gives us slices of family life that sound reassuringly familiar to anyone acquainted with the quiet existence of country people. In Brewster's poems, uncles, aunts, grandparents, relatives and friends meet in their warm and cosy homes to talk about the weather, the interests of the community or to comply dutifully with the social task of mourning one of their elders. However, to take Elizabeth Brewster's poems literally is not to do them justice. Beneath the simplicity of form and content of her pieces is a world full of larger -182- THE HGMEMRKEBS significances that the analysis of one of her prairie poems will help to unveil. The poem is entitled "The Future of Poetry in Canada" and is, at its most immediate level, a chronicle of prairie life in a small community. Elizabeth Brewster takes us to Goodridge, Alberta 'where electricity arrived in 1953/ the telephone in 1963', and introduces us to its people for whom the most important social activities are 'the golden wedding anniversaries of the residents' and 'the farewell parties', all of them 'well attended in spite of the blizzards' . At these gatherings, through which Brewster highlights the sense of community as a therapy against loneliness, people talk about the weather and 'remember the time they threshed in the snow/ and the winter the temperature fell to seventy below'. -

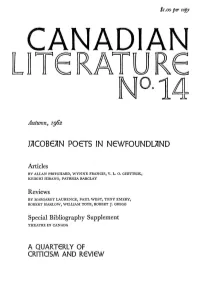

Jacobean P06ts in Newfoundland

$i.oo per copy Autumn, ig62 JACOBEAN P06TS IN NEWFOUNDLAND Articles BY ALLAN PRITCHARD, WYNNE FRANCIS, V. L. 1 , 1 HIRANO, PATRICIA BARCLAY Reviews BY MARGARET LAU R E N C E, P AU L WEST, TONY EMERY, ROBERT HARLOW, WILLIAM TO YE , ROBERT J. GREGG Special Bibliography Supplement THEATRE IN CANADA A QUARTERLY OF CRITICISM AND R6VI6W CAUTIOUS INEVITABILITY PROFESSOR DESMOND PACEY has rendered many services to writing in Canada, and particularly as the only considerable historian of literature in English-speaking Canada. To these we can now add another service, less sub- stantial, but no less satisfying in its own way — that of persuading the Times Literary Supplement to admit, after having implicitly denied it twelve years ago, that something which can be called a "Canadian literature" has at last come into being. The new edition of Professor Pacey's Creative Writing in Canada — recently released in England — was the subject not merely of a review, but of an editorial in the TLS which has some salutary things to say about both the character of Canadians and that character's relation to their literary productions. No one need mistake a Canadian for other than what he is; and if "character" is given a more particular interpretation, the Canadian is as resolute as any other national in asserting his identity, in the face of considerable odds. England on the one hand and the United States on the other are set to lure him off his inde- pendent track. But whether it is that the caution needed for such a difficult navi- gation spoils with self-consciousness the free expression of his identity, or that his character in its realization on a national scale does not insist upon being imagi- natively interpreted, it is certain that he has fallen behind other Commonwealth countries in arousing curiosity abroad and establishing a sympathetic image.