May He Speedily Come the Role of the Messiah in Haredi and Hardal Judaism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE APOCALYPTIC WAR AGAINST GOG of MAGOG. MARTIN BUBER VERSUS MEIR KAHANE Por: Rico Sneller

EL CONFLICTO PALESTINO-ISRAELI: SOLUCIONES Y DERIVAS Profesor David Noel Ramírez Padilla Rector del Tecnológico de Monterrey Lic. Héctor Núñez de Cáceres Rector de la Zona Occidente Ing. Salvador Coutiño Audiffred Dr. Ricardo Romero Gerbaud Director General del Campus Querétaro Dirección Dr. Ricardo Romero Gerbaud Mtro. José Manuel Velázquez Hurtado Director de Profesional y Graduados en María José Juárez Becerra Administración y Ciencias Sociales Edición Mtra. Angélica Camacho Aranda Natalia Fernández, Alicia Hernández, Rodrigo Directora del Departamento de Relaciones Pesce Internacionales y Formación Humanística Asistentes de Edición Mtro. Kacper Przyborowski Director de la Licenciatura en Relaciones Internacionales Dr. Tomás Pérez Vejo Dra. Marisol Reyes Soto Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia INAH University of Queens, Ireland Dra. Avital Bloch Dr. Tamir Bar-On Universidad de Colima Tecnológico de Monterrey Dra. Marie-Joelle Zahar Université de Montréal Dra. Claudia Barona Castañeda Universidad de Las Américas Puebla Dr. Thomas Wolfe University of Minnesota, Twin-Cities Dr. Janusz Mucha AGH, Cracovia GRUPO FORUM Retos Internacionales, ISSN: 2007-8390. Año 5, No. 11, Agosto-Diciembre 2014, publicación semestral. Editada por el Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, Campus Querétaro, a través de la División de Administración y Ciencias Sociales, bajo la dirección del Departamento deRelaciones Internacionales y Humanidades, domicilio Av. Eugenio Garza Sada No. 2501, Col. Tecnológico, C.P. 64849, Monterrey, N.L. Editor responsable: Dr. Ricardo Romero Gerbaud. Datos de contacto: [email protected], http://retosinternacionales.com, teléfono y fax: 52 (442) 238 32 34. Impresa por FORUM arte y comunicación S.A. de C.V., domicilio Av. del 57, número 12, Colonia Centro, C.P. -

Zionism - a Successor to Rabbinical Judaism?

Zionism - A Successor to Rabbinical Judaism? By Gol Kalev Outline I) Introduction II) Historical Background -Judaism to Zionism -Zionism as a Successor to Rabbinical Judaism? Why It Has Not Happened So Far: -Israel-Related Hurdles -America-Related Hurdles III) Transformation of Judaism: Why Now Might Be a Ripe Time: -Changing Circumstances in Israel -New Threats (Post-Zionism) -Enablers of Jewish Transformation -Changing Circumstances in America -New Threats (End of Jewish Glues, Israel-Bashing, Dispersal of Jewish Capital) -Enablers of Jewish Transformation IV) Judaism 3.0 2 INTRODUCTION “Palestine for the Jews!” That was the headline of The London Times on November 9, 1917, the week after the British government issued the Balfour Declaration. A mere 30 years later, the headline turned into reality with the establishment of the State of Israel, homeland of the Jewish People. The return of the Jews to their ancestral homeland has driven Rabbinical Judaism, the form of Judaism practiced for the last 1900 years, to a unique challenge. After all, Rabbinical Judaism’s formation coincided with the Jews’ exit to the Diaspora, and to a large extent was developed to accommodate the state of exile. Much of its core is based on the yearning for the return to Israel. The propensity of its rituals, prayers and customs are centered on the Land of Israel, from having synagogues face Jerusalem to reciting a prayer for return three times a day. A question arose: Now that the Jews are allowed to return to the Land of Israel, how will Judaism evolve? During the 20th century, the Jewish people re-domiciled and concentrated in two core centers: Israel and the United States. -

Daat Torah (PDF)

Daat Torah Rabbi Alfred Cohen Daat Torah is a concept of supreme importance whose specific parameters remain elusive. Loosely explained, it refers to an ideology which teaches that the advice given by great Torah scholars must be followed by Jews committed to Torah observance, inasmuch as these opinions are imbued with Torah insights.1 Although the term Daat Torah is frequently invoked to buttress a given opinion or position, it is difficult to find agreement on what is actually included in the phrase. And although quite a few articles have been written about it, both pro and con, many appear to be remarkably lacking in objectivity and lax in their approach to the truth. Often they are based on secondary source and feature inflamma- tory language or an unflatttering tone; they are polemics rather than scholarship, with faulty conclusions arising from failure to check into what really was said or written by the great sages of earlier generations.2 1. Among those who have tackled the topic, see Lawrence Kaplan ("Daas Torah: A Modern Conception of Rabbinic Authority", pp. 1-60), in Rabbinic Authority and Personal Autonomy, published by Jason Aronson, Inc., as part of the Orthodox Forum series which also cites numerous other sources in its footnotes; Rabbi Berel Wein, writing in the Jewish Observer, October 1994; Rabbi Avi Shafran, writing in the Jewish Observer, Dec. 1986, p.12; Jewish Observer, December 1977; Techumin VIII and XI. 2. As an example of the opinion that there either is no such thing now as Daat Torah which Jews committed to Torah are obliged to heed or, even if there is, that it has a very limited authority, see the long essay by Lawrence Kaplan in Rabbinic Authority and Personal Autonomy, cited in the previous footnote. -

Israel's National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

Leap of Faith: Israel’s National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict Middle East Report N°147 | 21 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iv I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Religious Zionism: From Ascendance to Fragmentation ................................................ 5 A. 1973: A Turning Point ................................................................................................ 5 B. 1980s and 1990s: Polarisation ................................................................................... 7 C. The Gaza Disengagement and its Aftermath ............................................................. 11 III. Settling the Land .............................................................................................................. 14 A. Bargaining with the State: The Kookists ................................................................... 15 B. Defying the State: The Hilltop Youth ........................................................................ 17 IV. From the Hills to the State .............................................................................................. -

CV July 2017

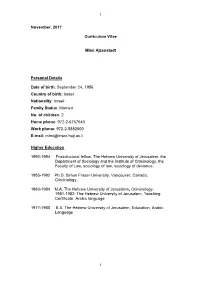

1 November, 2017 Curriculum Vitae Mimi Ajzenstadt Personal Details Date of birth: September 24, 1956 Country of birth: Israel Nationality: Israeli Family Status: Married No. of children: 2 Home phone: 972-2-6767540 Work phone: 972-2-5882600 E-mail: [email protected] Higher Education 1992-1994 Post-doctoral fellow, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Department of Sociology and the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law, sociology of law, sociology of deviance. 1985-1992 Ph.D. Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada, Criminology. 1980-1984 M.A. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Criminology. 1981-1982: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Teaching Certificate, Arabic language 1977-1980 B.A. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Education, Arabic Language 1 2 Appointments at the Hebrew University 2012- present Full Professor, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 2007– 2012 Associate Professor, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 2002- 2007 Senior Lecturer, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 1994-2002 Lecturer, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work. Service in other Academic Institutions Summer, 2011 Visiting Professor, Cambridge University. Summer, 2010 Visiting Professor. University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. 2005 -2006 Visiting Professor. University of Maryland, Maryland, USA. Winter, 2000 Visiting Scholar. Stockholm University, Sweden. Fall 1999 Visiting Scholar. Yale University, New-Haven, Connecticut, U.S.A., Law School. -

A Tribu1e 10 Eslller, Mv Panner in Torah

gudath Israel of America's voice in kind of informed discussion and debate the halls of courts and the corri that leads to concrete action. dors of Congress - indeed every A But the convention is also a major where it exercises its shtadlonus on yardstick by which Agudath Israel's behalf of the Kial - is heard more loudly strength as a movement is measured. and clearly when there is widespread recognition of the vast numbers of peo So make this the year you ple who support the organization and attend an Agm:fah conventicm. share its ideals. Resente today An Agudah convention provides a forum Because your presence sends a for benefiting from the insights and powerfo! - and ultimately for choice aa:ommodotions hadracha of our leaders and fosters the empowering - message. call 111-m-nao is pleased to announce the release of the newest volume of the TlHllE RJENNlERT JED>JITJION ~7~r> lEN<ClY<ClUO>lPElOl l[}\ ~ ·.:~.~HDS. 1CA\J~YA<Gr M(][1CZ\V<Q . .:. : ;······~.·····················.-~:·:····.)·\.~~····· ~s of thousands we~ed.(>lig~!~d~ith the best-selling mi:i:m niw:.r c .THE :r~~··q<:>Jy(MANDMENTS, the inaugural volume of theEntzfl(lj)('dia (Mitzvoth 25-38). Now join us aswestartfromthebeginning. The En~yclop~dia provides yau with • , • A panciramicviewofthe entire Torah .Laws, cust9ms and details about each Mitzvah The pririlafy reasons and insights for each Mitzvah. tteas.. ury.· of Mid. ra. shim and stories from Cha. zal... and m.uc.h.. n\ ''"'''''' The Encyclopedia of the Taryag Mitzvoth The Taryag Legacy Foundation is a family treasure that is guaranteed to wishes to thank enrich, inspire, and elevate every Jewish home. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13864-3 — the Israeli Settler Movement Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler , Cas Mudde Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13864-3 — The Israeli Settler Movement Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler , Cas Mudde Index More Information Index 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the, 2 Ariel, Uri, 76, 116 1949 Armistice Agreements, the, 2 Arutz Sheva, 120–121, 154, 205 1956 Sinai campaign, the, 60 Ashkenazi, 42, 64, 200 1979 peace agreement, the, 57 Association for Retired People, 23 Australia, 138 Abrams, Eliott, 59 Aviner, Shlomo, 65, 115, 212 Academic Council for National, the. See Professors for a Strong Israel B’Sheva, 120 action B’Tselem, 36, 122 connective, 26 Barak, Ehud, 50–51, 95, 98, 147, 235 extreme, 16 Bar-Ilan University, 50, 187 radical, 16 Bar-Siman-Tov, Yaacov, 194, 216 tactical, 34 Bat Ayin Underground, the, 159 activism BDS. See Boycott, Divestment and moderate, 15–16 Sanctions transnational, 30–31 Begin, Manahem, 47, 48, 118–119, Adelson, Sheldon, 179, 190 157, 172 Airbnb, 136 Beit El, 105 Al Aqsa Mosque, the, 146 Beit HaArava, 45 Al-Aqsa Intifada. See the Second Intifada Beitar Illit, 67, 70, 99 Alfei Menashe, 100 Beitar Ironi Ariel, 170 Allon, Yigal, 45–46 Belafonte, Harry, 14 Alon Shvut, 88, 190 Ben Ari, Michael, 184 Aloni, Shulamit, 182 Bendaña, Alejandro, 24 Altshuler, Amos, 189 Ben-Gurion, David, 46 Amana, 76–77, 89, 113, 148, 153–154, 201 Ben-Gvir, Itamar, 184 American Friends of Ariel, 179–180 Benn, Menachem, 164 American Studies Association, 136 Bennett, Naftali, 76, 116, 140, 148, Amnesty International, 24 153, 190 Amona, 79, 83, 153, 157, 162, 250, Benvenisti, Meron, 1 251 Ben-Zimra, Gadi, 205 Amrousi, Emily, 67, 84 Ben-Zion, -

Tahoe Community Church

Tahoe Community Church Notes, Announcements, Needs and Reminders February 2019 Worshiping Together, Making Disciples, Reaching our World Christmas Pictures Sunday Worship Schedule “Let the 9:00 a.m. Sunday Morning Study Classes little 9:30 a.m. Praise Team Warm Up children come to 10:10 a.m. Coffee/Fellowship Time me” 10:30 a.m. Worship Service (Nursery and Children’s Church Available) Matthew 19:14 5:00 p.m. Youth Group in the MPR Weekly Church Activities Wednesday 7:00 a.m. Men’s Bible Study Fellowship at Lakeside upstairs restaurant 8:30 a.m. Prayer Gathering 9:30 a.m. Knitting Group 5:00 p.m. Praise Team Practice Thursday 9:00 a.m. Women’s Morning Study 3:30 p.m. Awesome Kids 5:30 p.m. Women’s Evening Study 6:00 p.m. Men’s Bible Study A Shoebox Response Hello Pastor Mondo, Aliana A warm Christmas greetings and & prayful wishes! I am a Catholic Brooklyn Nun, Sister Anna Mao, from India. Just today we have received your beautiful Gift you sent our children. We cater to HIV patients’ children and orphans. Our children are trilled to receive your gift box filled with love. Thanks a lot for sharing this Christmas joy with our children. God bless you and your family a hundred fold in re- turn! Will remain indebted to you. With love and prayers, Sister Anna Christmas Eve children’s Note: These boxes contain God’s word and He says: “So is my word that goes out from my mouth: It will message not return to me empty but will accomplish what I desire and achieve the purpose I for which I sent it.” Isiah 55:10-11 145 Daggett Way — Stateline, Nevada 89449 — (775) 588-5860 — [email protected] — www.tahoecommunitychurch.org Office Telephone Extensions: Mondo 101, Ted-103, Sarah and Preschool-107. -

Rav Kook and Dr. Revel: a Shared Vision for a Central Universal Yeshiva?

NATAN OPHIR Rav Kook and Dr. Revel: A Shared Vision for a Central Universal Yeshiva? his article examines a little known episode in the history of two famous schools, Yeshivat Mercaz HaRav-Central Universal TYeshiva (CUY) 1 and the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (RIETS). Specifically, it examines several exchanges between R. Abraham Isaac Kook and R. Dr. Bernard Revel. Their discussion began in 1918, continued when R. Kook visited New York in 1924, and culminated in a written proposal by Dr. Revel on May 17, 1927. The proposal would have meant uniting what we now call the Torah u- Madda 2 ideology developed in New York with Torat Ere z. Yisrael of Jerusalem. There are lacunae in this story that leave room for speculation. Nevertheless, the main plot will, I believe, be of special interest to read - ers of this journal, and may give rise to interesting observations about the protagonists. Besides adding a chapter to the history of Torah u- Madda in the twentieth century, this story provides a glimpse into a rel - atively unknown phase in the early development of both Yeshiva College and CUY. NATAN OPHIR (O FFENBACHER ) directs Meorot, a center in Jerusalem for Jewish Meditation and Neuro-Psychology. An alumnus of Yeshiva College, he received ordination from Yeshivat Mercaz HaRav and a Ph.D in Jewish Philosophy at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where he served as rabbi of the campus for sixteen years. He has published articles in Daat , Tehumin , and other scholarly journals. 188 The Torah u-Madda Journal (15/2008-09) Natan Ophir 189 R. -

“IN the BAG” Iences Today Enjoyed by Ed Matters

ww ww VOLUME s h / NO. 5 SHEVAT 5766 / FEBRUARY 2006 s xc THEDaf HaKashrus A MONTHLY NEWSLETTER FOR THEU RABBINIC FIELD REPRESENTATIVE AND DAF NOTES: For over a year, on a weekly basis, the U has provided the announced that these high quality articles will be collected and pub- popular Hamodia newspaper with a quality Kashruth article written by U lished by the OU as a book in the near future. Kashruth personnel. These articles appeared in a column entitled Kashrus Anyone interested in contributing future articles should contact Kaleidoscope. The responsibility of providing these excellent articles to Hamodia Rabbi Buchbinder by phone at 212-613-8344, fax 212-613-0720 or was superbly shouldered by Rabbi Avram Ossey. This responsibility has now been email [email protected]. assumed by Rabbi Gad Buchbinder. He will be ably assisted by the editorial board The Daf HaKashrus is pleased to publish, with permission, the fol- consisting of Rabbis Luban, Cohen, Price, Gorelik and Scheiner who previously lowing pertinent article by Rabbi Dovid Bistricer which first assisted Rabbi Ossey as well. appeared in Hamodia. It discusses leafy vegetables and insect infes- At a recent Kashruth staff meeting, Rabbi Genack announced the awarding of an tation – an issue which has recently been widely discussed here in honorarium of $200 to any RC or RFR whose article is henceforth accepted by the America. OU to be included in this column, subject to certain conditions. He also ages of up to 60 insects per 100 grams in frozen broccoli, and up to 50 insects per 100 grams of frozen spinach (See Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act 402 (a)(3)). -

Jewish Eugenics, and Other Essays

JEWISH EUGENICS AND OTHER ESSAYS THREE PAPERS READ BEFORE THE NEW YORK BOARD OF JEWISH MINISTERS 1915 I JEWISH EUGENICS By Rabbi Max Reichler II THE DEFECTIVE IN JEWISH LAW AND LITERATURE By Rabbi Joel Blau III CAPITAL PUNISHMENT AMONG THE JEWS By Rev. Dr. D. de Sola Pool NEW YORK BLOCH PUBLISHING COMPANY 1916 <=> k Copyright, 1916, by BLOCH PUBLISHING COMPANY CONTENTS I. Jewish Eugenics 7 II. The Defective in Jewish Law and Literature 23 III. Capital Punishment Among the Jews . 53 424753 Jewish Eugenics Rabbi Max Reichler. B. A. JEWISH EUGENICS Who knows the cause of Israel's survival? Why- did the Jew survive the onslaughts of Time, when others, numerically and politically stronger, suc- cumbed? Obedience to the Law of Life, declares the modern student of eugenics, was the saving quality which rendered the Jewish race immune from disease and destruction. "The Jews, ancient and modern," says Dr. Stanton Coit, "have always understood the science of eugenics, and have gov- erned themselves in accordance with it; hence the 1 preservation of the Jewish race." I. Jewish Attitude To be sure eugenics as a science could hardly have existed among the ancient Jews; but many eugenic rules were certainly incorporated in the large collection of Biblical and Rabbinical laws. Indeed there are clear indications of a conscious effort to utilize all influences that might improve the inborn qualities of the Jewish race, and to guard against any practice that might vitiate the purity of 1 Ci. also Social Direction of Human Evolution, by Prof. William E. Kellicott, 1911, p. -

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach Today (?)

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach today (?) Three girls in Israel were detained by the Israeli Police (2018). The girls are activists of the “Return to the Mount” (Chozrim Lahar) movement. Why were they detained? They had posted Arabic signs in the Muslim Quarter calling upon Muslims to leave the Temple Mount area until Friday night, in order to allow Jews to bring the Korban Pesach. This is the fourth time that activists of the movement will come to the Old City on Erev Pesach with goats that they plan to bring as the Korban Pesach. There is also an organization called the Temple Institute that actively is trying to bring back the Korban Pesach. It is, of course, very controversial and the issues lie at the heart of one of the most fascinating halachic debates in the past two centuries. 1 The previous mishnah was concerned with the offering of the paschal lamb when the people who were to slaughter it and/or eat it were in a state of ritual impurity. Our present mishnah is concerned with a paschal lamb which itself becomes ritually impure. Such a lamb may not be eaten. (However, we learned incidentally in our study of 5:3 that the blood that gushed from the lamb's throat at the moment of slaughter was collected in a bowl by an attendant priest and passed down the line so that it could be sprinkled on the altar). Our mishnah states that if the carcass became ritually defiled, even if the internal organs that were to be burned on the altar were intact and usable the animal was an invalid sacrifice, it could not be served at the Seder and the blood should not be sprinkled.