Goyescas: a Performer’S Guide by Kristin Newbegin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Intermediate-Level Solo Piano Music Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis Harumi Kurihara Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kurihara, Harumi, "Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3242. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SELECTED INTERMEDIATE-LEVEL SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF ENRIQUE GRANADOS: A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Harumi Kurihara B.M., Loyola University, New Orleans, 1993 M.M.,University of New Orleans, 1997 August, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my major professor, Professor Victoria Johnson for her expert advice, patience, and commitment to my monograph. Without her help, I would not have been able to complete this monograph. I am also grateful to my committee members, Professors Jennifer Hayghe, Michael Gurt, and Jeffrey Perry for their interest and professional guidance in making this monograph possible. I must also recognize the continued encouragement and support of Professor Constance Carroll who provided me with exceptional piano instruction throughout my doctoral studies. -

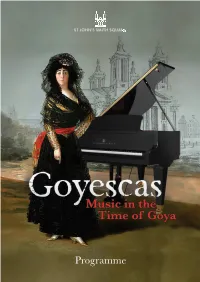

Music in the Time of Goya

Music in the Time of Goya Programme ‘Goyescas’: Music in the Time of Goya Some of the greatest names in classical music support the Iberian and Latin American Music Society with their membership 2 November 2016, 7.00pm José Menor piano Daniel Barenboim The Latin Classical Chamber Orchestra featuring: Argentine pianist, conductor Helen Glaisher-Hernández piano | Elena Jáuregui violin | Evva Mizerska cello Nicole Crespo O’Donoghue violin | Cressida Wislocki viola and ILAMS member with special guest soloists: Nina Corti choreography & castanets Laura Snowden guitar | Christin Wismann soprano Opening address by Jordi Granados This evening the Iberian and Latin American Music Society (ILAMS) pays tribute to one of Spain’s most iconic composers, Enrique Granados (1867–1916) on the centenary year of his death, with a concert programme inspired by Granados’ greatest muse, the great Spanish painter Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828), staged amidst the Baroque splendour of St John’s Smith Square – a venue which, appropriately, was completed not long before Goya’s birth, in 1728. Enrique Granados To pay homage to Granados here in London also seems especially fi tting given that the great Composer spent his fi nal days on British shores. Granados Will you drowned tragically in the English Channel along with his wife Amparo after their boat, the SS Sussex, was torpedoed by the Germans. At the height of his join them? compositional powers, Granados had been en route to Spain from New York where his opera, Goyescas, had just received its world premiere, and where he had also given a recital for President Woodrow Wilson; in his lifetime Granados was known as much for his virtuoso piano playing as for his talent as a composer. -

Granados: Goyescas

Goyescas Enrique Granados 1. Los Requiebros [9.23] 2. Coloquio en La Reja [10.53] 3. El Fandango de Candil [6.41] 4. Quejas, ó la Maja y el Ruiseñor [6.22] 5. El Amor y la Muerte: Balada [12.43] 6. Epilogo: Serenata del Espectro [7.39] Total Timings [54.00] Ana-Maria Vera piano www.signumrecords.com The Goyescas suite has accompanied me throughout with her during the recording sessions and felt G my life, and I always knew that one day I would generous and grounded like never before. The music attempt to master it.The rich textures and came more easily as my perspectives broadened aspiring harmonies, the unfurling passion and I cared less about perfection. Ironically this is tempered by restraint and unforgiving rhythmic when you stand the best chance of approaching precision, the melancholy offset by ominous, dark your ideals and embracing your audience. humour, the elegance and high drama, the resignation and the hopefulness all speak to my sense of © Ana-Maria Vera, 2008 being a vehicle, offeeling the temperature changes, the ambiguity, and the emotion the way an actor might live the role of a lifetime. And so this particular project has meant more to me than almost any in my career. Catapulted into the limelight as a small child, I performed around the globe for years before realising I had never had a chance to choose a profession for myself. Early success, rather than going to my head, affected my self-confidence as a young adult and I began shying away from interested parties, feeling the attention wasn't deserved and therefore that it must be of the wrong kind. -

American 1Wusic Has Not Yet Uarrived'', Declares

' / 16 MUSICAL AMERICA September 6, 1919 store .employees who have their daily sings are a more efficient and happier lot of workers than those who do not, and American 1Wusic Has Not Yet uArrived'', he is convinced that the same will appl1 to singers in any other vocation. So it will not be a surprising thing Declares New Leader of Boston Symphony to enter the city hall at lunch time hereafter and hear city surveyors, tax Pierre Monteux, Back from F ranee, Begins Rehearsals-" Let Us Forget the War; It H as No Part collectors, policemen off duty and other eaters blending their melodious voices in in the Selection of Programs," Says Parisian the interpretation of a nything from jazz to grand opera. H. P. ~ OSTON, Aug. 29-With the arrival our best in literature and in poetry re 'dance s·pir·it' which characterizes Rus B her e this week of P ierre Moriteux, ma ins and always will be dear to us. sian music-not of the same style as NOTABLE MU SICIANS that of Russia but with a style char the new Boston Symphony Orchest r-a His View of American Music acteristically American. JOIN PEABODY STAFF conductor, the stage is fast being set f or "You ask whether we ar e t o develop "I think it will come. It will be very a Symphony season of rare distinct ion a true American type of music. Yes, or iginal; very American." Baltimore Conservatory Opens on Sept. and success. M. Monteux, with Mme. perhaps so, but the time has not arrived Mr. -

Arriva Un Bastimento Carico Di Artisti. Sulle Tracce Della Cultura Italiana Nella Buenos Aires Del Centenario

RiMe Rivista dell’Istituto di Storia dell’Europa Mediterranea ISSN 2035-794X numero 6, giugno 2011 Arriva un bastimento carico di artisti. Sulle tracce della cultura italiana nella Buenos Aires del Centenario Irina Bajini Istituto di Storia dell’Europa Mediterranea Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche http://rime.to.cnr.it ! " # $ O P % & " ' ()% !! '* " " ! ' ) I ' % & * % & ,& " & ' - !! * - ' "." % ! " " 0 !! 0 % # &$ '--'-1' 1 1--) ' !! ' 'R' 3 M )'R ' 'R' *355-666 5 7 70 6)897:9:8;! !19::<=9>=?95?=;@7%A9::B:8;>@? &3 &6-C-66 '3 '6-C-66 ) ! "# $% &" ' $%!" '(" " " )% $%% &%! *% + , -# ' ". / " "" )#! %0 & ' &'"%% ' %" R" & '% !##" '+#" % %3! " 4 ##% " % "5' $# #!!. 6! %'7 ! %8 %! %' ' &! 5 ! )% " 7 ! % "% ' 0 9%" $ %% $ %" ' #"% %"%' ) % (% #(!! 7R%!.""" %' R& %0 " % " %3 7 "%" %& %" 3 %&!' ! !!! % " 7 => " *'& ' 4&!#( # O @ #' &"P % ! &%7%%#"0 ' R&& %0 " % "' % &0 %'3Q %&9% $% #"" "%!.!" ""%" %% "' #! %)@ %% 9#"&" !%! '%"#" "%!!' ! " % " ) #%#' ("% '! ! 7 C * "% ' # % # ' * % @ D!! ' 4 3 #!."" #9 !. M %&4 %#C & @%# #"# % & @%# " # + % "# %! #' # %(%#"F%'G !.#=9F *&%##+&%#% #" #' ("% ' % " "%#" ' '% " # % 3 # ) % 5 & " &#" #"% "%% ' #9'%"# $ " $ %0 ! '' + (" !#& * '#%% ' ' ' ! ! "K" ' % ' !! " !" ' -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 35,1915-1916, Trip

SANDERS THEATRE . CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY ^\^><i Thirty-fifth Season, 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor ITTr WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE THURSDAY EVENING, MARCH 23 AT 8.00 COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER 1 €$ Yes, It's a Steinway ISN'T there supreme satisfaction in being able to say that of the piano in your home? Would you have the same feeling about any other piano? " It's a Steinway." Nothing more need be said. Everybody knows you have chosen wisely; you have given to your home the very best that money can buy. You will never even think of changing this piano for any other. As the years go by the words "It's a Steinway" will mean more and more to I you. and thousands of times, as you continue to enjoy through life the com- panionship of that noble instrument, absolutely without a peer, you will say to yourself: "How glad I am I paid the few extra dollars and got a Steinway." pw=a I»3 ^a STEINWAY HALL 107-109 East 14th Street, New York Subway Express Station at the Door Represented by the Foremost Dealers Everywhere Thirty-fifth Season, 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Violins. Witek, A. Roth, O. Hoffmann, J. Rissland, K. Concert-master. Koessler, M. Schmidt, E. Theodorowicz, J. Noack, S. Mahn, F. Bak, A. Traupe, W. Goldstein, H. Tak, E. Ribarsch, A. Baraniecki, A. Sauvlet. H. Habenicht, W. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Goldstein, S. Fiumara, P. Spoor, S. Sulzen, H. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL CHARACTER AS EXPRESSED IN PIANO LITERATURE Yong Sook Park, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2005 Dissertation directed by: Bradford Gowen, Professor of Music In the middle of the 19th century, many composers living outside of mainstream musical countries such as Germany and France attempted to establish their own musical identity. A typical way of distinguishing themselves from German, French, and Italian composers was to employ the use of folk elements from their native lands. This resulted in a vast amount of piano literature that was rich in national idioms derived from folk traditions. The repertoire reflected many different national styles and trends. Due to the many beautiful, brilliant, virtuosic, and profound ideas that composers infused into these nationalistic works, they took their rightful place in the standard piano repertoire. Depending on the compositional background or style of the individual composers, folk elements were presented in a wide variety of ways. For example, Bartók recorded many short examples collected from the Hungarian countryside and used these melodies to influence his compositional style. Many composers enhanced and expanded piano technique. Liszt, in his Hungarian Rhapsodies, emphasized rhythmic vitality and virtuosic technique in extracting the essence of Hungarian folk themes. Chopin and Szymanowski also made use of rhythmic figurations in their polonaises and mazurkas, often making use of double-dotted rhythms. Obviously, composers made use of nationalistic elements to add to the piano literature and to expand the technique of the piano. This dissertation comprises three piano recitals presenting works of: Isaac Albeniz, Bela Bartók, Frédéric Chopin, Enrique Granados, Edvard Grieg, Franz Liszt, Frederic Rzewski, Alexander Scriabin, Karol Szymanowski, and Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky. -

Repertoire Report 2012-13 Season Group 7 & 8 Orchestras

REPERTOIRE REPORT 2012-13 SEASON GROUP 7 & 8 ORCHESTRAS Composer Work First Perf. Conductor Orchestra Soloist(s) Actor, Lee DIVERTIMENTO FOR SMALL ORCHESTRA Apr. 27, 2013 Emily Ray Mission Chamber Orchestra Adams, John SHORT RIDE IN A FAST MACHINE Oct. 13, 2012 Fouad Fakhouri Fayetteville Symphony Orchestra Bach, J. S. TOCCATA AND FUGUE, BWV 565, D MINOR Oct. 27, 2012 Charles Latshaw Bloomington Symphony (STOWKOWSKI) (STOWKOWSKI,) Orchestra Barber, Samuel CONCERTO, VIOLIN AND ORCHESTRA, Feb. 2, 2013 Jason Love The Columbia Orchestra Madeline Adkins, violin OPUS 14 Barber, Samuel OVERTURE TO THE SCHOOL FOR Feb. 9, 2013 Herschel Kreloff Civic Orchestra of Tucson SCANDAL Bartok, Béla ROMANIAN FOLK DANCES Sep. 29, 2012 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra Beethoven, Ludwig V. CONCERTO, PIANO, NO. 5 IN E-FLAT Apr. 14, 2013 Joel Lazar Symphony of the Potomac Sayaka Jordan, piano MAJOR, OP. 73 Beethoven, Ludwig V. CONCERTO, VIOLIN, IN D MAJOR, OPUS Nov. 17, 2012 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra Sharon Roffman, violin 61 Beethoven, Ludwig V. CORIOLAN: OVERTURE, OPUS 62 Mar. 9, 2013 Fouad Fakhouri Fayetteville Symphony Orchestra Apr. 14, 2013 Joel Lazar Symphony of the Potomac Beethoven, Ludwig V. EGMONT: OVERTURE, OPUS 84 Oct. 20, 2012 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra Beethoven, Ludwig V. SONATA FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO, Apr. 13, 2013 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra "SPRING" III RONDO Beethoven, Ludwig V. SYMPHONY NO. 1 IN C MAJOR, OPUS 21 Apr. 27, 2013 Emily Ray Mission Chamber Orchestra Beethoven, Ludwig V. SYMPHONY NO. 3 IN E-FLAT MAJOR, Apr. 14, 2013 Joel Lazar Symphony of the Potomac OPUS 55 Page 1 of 13 REPERTOIRE REPORT 2012-13 SEASON GROUP 7 & 8 ORCHESTRAS Composer Work First Perf. -

María Del Carmen Opera in Three Acts

Enrique GRANADOS María del Carmen Opera in Three Acts Veronese • Suaste Alcalá • Montresor Wexford Festival Opera Chorus National Philharmonic Orchestra of Belarus Max Bragado-Darman CD 1 43:33 5 Yo también güervo enseguía Enrique (Fuensanta, María del Carmen) 0:36 Act 1 6 ¡Muy contenta! y aquí me traen, como aquel GRANADOS 1 Preludio (Orchestra, Chorus) 6:33 que llevan al suplicio (María del Carmen) 3:46 (1867-1916) 2 A la paz de Dios, caballeros (Andrés, Roque) 1:28 7 ¡María del Carmen! (Pencho, María del Carmen) 5:05 3 Adiós, hombres (Antón, Roque) 2:27 8 ¿Y qué quiere este hombre a quien maldigo María del Carmen 4 ¡Mardita sea la simiente que da la pillería! desde el fondo de mi alma? (Pepuso, Antón) 1:45 (Javier, Pencho, María del Carmen) 4:10 Opera in Three Acts 9 5 ¿Pos qué es eso, tío Pepuso? ¡Ah!, tío Pepuso, lléveselo usted (Roque, Pepuso, Young Men) 3:04 (María del Carmen, Pepuso, Javier, Pencho) 0:32 Libretto by José Feliu Codina (1845-1897) after his play of the same title 0 6 ¡Jesús, la que nos aguarda! Ya se fue. Alégrate corazón mío Critical Edition: Max Bragado-Darman (Don Fulgencio, Pepuso, Roque) 1:49 (María del Carmen, Javier) 0:55 ! ¡Viva María el Carmen y su enamorao, Javier! Published by Ediciones Iberautor/Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales 7 Una limosna para una misa de salud… (Canción de la Zagalica) (María del Carmen, (Chorus, Domingo) 5:22 @ ¡Pencho! ¡Pencho! (Chorus) ... Vengo a delatarme María del Carmen . Diana Veronese, Soprano Fuensanta, Don Fulgencio, Pepuso, Roque) 6:59 8 Voy a ver a mi enfermo, el capellán para salvar a esta mujer (Pencho, Domingo, Concepción . -

Il Trittico Pucciniano

GIACOMO PUCCINI IL TRITTICO PUCCINIANO Il trittico viene rappresentato per la prima volta al Teatro Metropolitan di New York il 14 dicembre 1918. Il tabarro - Luigi Montesanto (Michele); Giulio Crimi (Luigi), Claudia Muzio (Giorgetta); Suor Angelica - Geraldine Farrar (Suor Angelica), Flora Perini (Zia Principessa); Gianni Schicchi - Giuseppe de Luca (Gianni Schicchi), Florence Easton (Lauretta), Giulio Crimi (Rinuccio); direttore d'orchestra Roberto Moranzoni. La prima italiana ha luogo, meno d'un mese dopo, al Teatro Costanzi (odierno Teatro dell'opera di Roma) l'undici gennaio 1919, sotto la prestigiosa direzione di Gino Marinuzzi, fra gli interpreti principali: Gilda dalla Rizza, Carlo Galeffi, Edoardo de Giovanni, Maria Labia, Matilde Bianca Sadun. L'idea d'un "Trittico" - inizialmente Puccini aveva pensato a tre soggetti tratti dalla Commedia dantesca, poi a tre racconti di autori diversi - si fa strada nella mente del Maestro almeno un decennio prima, già a partire dal 1905, subito a ridosso di Madama Butterfly. Tuttavia, sia questo progetto sia quello d'una "fantomatica" Maria Antonietta (che, come si sa, non fu mai realizzata) vengono per il momento accantonati in favore della Fanciulla del West (1910). La fantasia pucciniana è rivisitata dall'immagine d'un possibile "trittico" nel 1913, proprio mentre proseguono - gli incontri con Gabriele D'Annunzio per una possibile Crociata dei fanciulli...... Infatti, proprio nel febbraio di quello stesso anno Puccini è ripreso dall'urgenza del "trittico": immediatamente avvia il lavoro sul primo dei libretti che viene tratto da La Houppelande, un atto unico, piuttosto grandguignolesco, di Didier Gold, cui il compositore aveva assistito, pochi mesi prima, in un teatro parigino: sarà Il tabarro, abilmente ridotto a libretto da Giuseppe Adami. -

CYLINDERS 2M = 2-Minute Wax, 4M WA= 4-Minute Wax, 4M BA = Edison Blue Amberol, OBT = Original Box and Top, OP = Original Descriptive Pamphlet

CYLINDERS 2M = 2-minute wax, 4M WA= 4-minute wax, 4M BA = Edison Blue Amberol, OBT = original box and top, OP = original descriptive pamphlet. ReproB/T = Excellent reproduction orange box and printed top Any mold on wax cylinders is always described. All cylinders are boxed (most in good quality boxes) with tops and are standard 2¼” diameter. All grading is visual. All cylinders EDISON unless otherwise indicated. “Direct recording” means recorded directly to cylinder, rather than dubbed from a Diamond-Disc master. This is used for cylinders in the lower 28200 series where there might be a question. BLANCHE ARRAL [s] 4108. Edison BA 28125. MIGNON: Je suis Titania (Thomas). Repro B/T. Just about 1-2. $40.00. ADELINA AGOSTINELLI [s]. Bergamo, 1882-Buenos Aires, 1954. A student in Milan of Giuseppe Quiroli, whom she later married, Agostinelli made her debut in Pavia, 1903, as Giordano’s Fedora. She appeared with success in South America, Russia, Spain, England and her native Italy and was on the roster of the Hammerstein Manhattan Opera, 1908-10. One New York press notice indicates that her rendering of the “Suicidio” from La Gioconda on a Manhattan Sunday night concert “kept her busy bowing in recognition to applause for three or four minutes”. At La Scala she was cast with Battistini in Simon Boccanegra and created for that house in 1911 the Marschallin in their first Rosenkavalier. Her career continued into the mid-1920s when she retired to Buenos Aires and taught. 4113. Edison BA 28159. LA TRAVIATA: Addio del passato (Verdi). ReproB/T. -

Enrico Caruso

NI 7924/25 Also Available on Prima Voce ENRICO CARUSO Opera Volume 3 NI 7803 Caruso in Opera Volume One NI 7866 Caruso in Opera Volume Two NI 7834 Caruso in Ensemble NI 7900 Caruso – The Early Years : Recordings from 1902-1909 NI 7809 Caruso in Song Volume One NI 7884 Caruso in Song Volume Two NI 7926/7 Caruso in Song Volume Three 12 NI 7924/25 NI 7924/25 Enrico Caruso 1873 - 1921 • Opera Volume 3 and pitch alters (typically it rises) by as much as a semitone during the performance if played at a single speed. The total effect of adjusting for all these variables is revealing: it questions the accepted wisdom that Caruso’s voice at the time of his DISC ONE early recordings was very much lighter than subsequently. Certainly the older and 1 CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA, Mascagni - O Lola ch’ai di latti la cammisa 2.50 more artistically assured he became, the tone became even more massive, and Rec: 28 December 1910 Matrix: B-9745-1 Victor Cat: 87072 likewise the high A naturals and high B flats also became even more monumental in Francis J. Lapitino, harp their intensity. But it now appears, from this evidence, that the baritone timbre was 2 LA GIOCONDA, Ponchielli - Cielo e mar 2.57 always present. That it has been missed is simply the result of playing the early discs Rec: 14 March 1910 Matrix: C-8718-1 Victor Cat: 88246 at speeds that are consistently too fast. 3 CARMEN, Bizet - La fleur que tu m’avais jetée (sung in Italian) 3.53 Rec: 7 November 1909 Matrix: C-8349-1 Victor Cat: 88209 Of Caruso’s own opinion on singing and the effort required we know from a 4 STABAT MATER, Rossini - Cujus animam 4.47 published interview that he believed it should be every singers aim to ensure ‘that in Rec: 15 December 1913 Matrix: C-14200-1 Victor Cat: 88460 spite of the creation of a tone that possesses dramatic tension, any effort should be directed in 5 PETITE MESSE SOLENNELLE, Rossini - Crucifixus 3.18 making the actual sound seem effortless’.