New Presences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VICTOR ESTRELLA BURGOS (Dom) DATE of BIRTH: August 2, 1980 | BORN: Santiago, Dominican Republic | RESIDENCE: Santiago, Dominican Republic

VICTOR ESTRELLA BURGOS (dOm) DATE OF BIRTH: August 2, 1980 | BORN: Santiago, Dominican Republic | RESIDENCE: Santiago, Dominican Republic Turned Pro: 2002 EmiRATES ATP RAnkinG HiSTORy (W-L) Height: 5’8” (1.73m) 2014: 78 (9-10) 2009: 263 (4-0) 2004: T1447 (3-1) Weight: 170lbs (77kg) 2013: 143 (2-1) 2008: 239 (2-2) 2003: T1047 (3-1) Career Win-Loss: 39-23 2012: 256 (6-0) 2007: 394 (3-0) 2002: T1049 (0-0) Plays: Right-handed 2011: 177 (2-1) 2006: 567 (2-2) 2001: N/R (2-0) Two-handed backhand 2010: 219 (0-3) 2005: N/R (1-2) Career Prize Money: $635,950 8 2014 HiGHLiGHTS Career Singles Titles/ Finalist: 0/0 Prize money: $346,518 Career Win-Loss vs. Top 10: 0-1 Matches won-lost: 9-10 (singles),4-5 (doubles) Challenger: 28-11 (singles), 4-7 (doubles) Highest Emirates ATP Ranking: 65 (October 6, 2014) Singles semi-finalist: Bogota Highest Emirates ATP Doubles Doubles semi-finals: Atlanta (w/Barrientos) Ranking: 145 (May 25, 2009) 2014 IN REVIEW • In 2008, qualified for 1st ATP tournament in Cincinnati (l. to • Became 1st player from Dominican Republic to finish a season Verdasco in 1R). Won 2 Futures titles in Dominican Republic in Top 100 Emirates ATP Rankings after climbing 65 places • In 2007, won 5 Futures events in U.S., Nicaragua and 3 on home during year soil in Dominican Republic • Reached maiden ATP World Tour SF in Bogota in July, defeating • In 2006, reached 3 Futures finals in 3-week stretch in the U.S., No. -

GLOBAL HISTORY and NEW POLYCENTRIC APPROACHES Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System Palgrave Studies in Comparative Global History

Foreword by Patrick O’Brien Edited by Manuel Perez Garcia · Lucio De Sousa GLOBAL HISTORY AND NEW POLYCENTRIC APPROACHES Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System Palgrave Studies in Comparative Global History Series Editors Manuel Perez Garcia Shanghai Jiao Tong University Shanghai, China Lucio De Sousa Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Tokyo, Japan This series proposes a new geography of Global History research using Asian and Western sources, welcoming quality research and engag- ing outstanding scholarship from China, Europe and the Americas. Promoting academic excellence and critical intellectual analysis, it offers a rich source of global history research in sub-continental areas of Europe, Asia (notably China, Japan and the Philippines) and the Americas and aims to help understand the divergences and convergences between East and West. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15711 Manuel Perez Garcia · Lucio De Sousa Editors Global History and New Polycentric Approaches Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System Editors Manuel Perez Garcia Lucio De Sousa Shanghai Jiao Tong University Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Shanghai, China Fuchu, Tokyo, Japan Pablo de Olavide University Seville, Spain Palgrave Studies in Comparative Global History ISBN 978-981-10-4052-8 ISBN 978-981-10-4053-5 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4053-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017937489 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018, corrected publication 2018. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

Chapter 2 China's Cars and Parts

Chapter 2 China’s cars and parts: development of an industry and strategic focus on Europe Peter Pawlicki and Siqi Luo 1. Introduction Initially, Chinese investments – across all industries in Europe – especially acquisitions of European companies were discussed in a relatively negative way. Politicians, trade unionists and workers, as well as industry representatives feared the sell-off and the subsequent rapid drainage of industrial capabilities – both manufacturing and R&D expertise – and with this a loss of jobs. However, with time, coverage of Chinese investments has changed due to good experiences with the new investors, as well as the sheer number of investments. Europe saw the first major wave of Chinese investments right after the financial crisis in 2008–2009 driven by the low share prices of European companies and general economic decline. However, Chinese investments worldwide as well as in Europe have not declined since, but have been growing and their strategic character strengthening. Chinese investors acquiring European companies are neither new nor exceptional anymore and acquired companies have already gained some experience with Chinese investors. The European automotive industry remains one of the most important investment targets for Chinese companies. As in Europe the automotive industry in China is one of the major pillars of its industry and its recent industrial upgrading dynamics. Many of China’s central industrial policy strategies – Sino-foreign joint ventures and trading market for technologies – have been established with the aim of developing an indigenous car industry with Chinese car OEMs. These instruments have also been transferred to other industries, such as telecommunications equipment. -

MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS and HOSTS Published April 2013 © 2013 Sportbusiness Group All Rights Reserved

THE BID BOOK MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS AND HOSTS Published April 2013 © 2013 SportBusiness Group All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher. The information contained in this publication is believed to be correct at the time of going to press. While care has been taken to ensure that the information is accurate, the publishers can accept no responsibility for any errors or omissions or for changes to the details given. Readers are cautioned that forward-looking statements including forecasts are not guarantees of future performance or results and involve risks and uncertainties that cannot be predicted or quantified and, consequently, the actual performance of companies mentioned in this report and the industry as a whole may differ materially from those expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. Author: David Walmsley Publisher: Philip Savage Cover design: Character Design Images: Getty Images Typesetting: Character Design Production: Craig Young Published by SportBusiness Group SportBusiness Group is a trading name of SBG Companies Ltd a wholly- owned subsidiary of Electric Word plc Registered office: 33-41 Dallington Street, London EC1V 0BB Tel. +44 (0)207 954 3515 Fax. +44 (0)207 954 3511 Registered number: 3934419 THE BID BOOK MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS AND HOSTS Author: David Walmsley THE BID BOOK MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS AND HOSTS -

Physical Map of the World, November 2011

Physical Map of the World, November 2011 AUSTRALIA Independent state Bermuda Dependency or area of special sovereignty Sicily / AZORES Island / island group 150 120 90 60 30 0 30 60 90 120 150 180 Capital Alert FRANZ JOSEF ARCTICARCTIC OCEANOCEAN ARCTICARCTIC OCEANOCEAN LAND SEVERNAYA ARCTICARCTIC OCEANOCEAN ZEMLYA Ellesmere Molloy Deep Longyearbyen QUEEN ELIZABETH Island Qaanaaq (Thule) (deepest point of the Arctic Ocean, -5607 m) NEW SIBERIAN ISLANDS Scale 1:35,000,000 Svalbard NOVAYA Kara Sea ISLANDS Greenland Sea ZEMLYA Laptev Sea Robinson Projection Banks (NORWAY) Barents Sea Island Resolute East Siberian Sea standard parallels 38°N and 38°S Pond Inlet Baffin Greenland Wrangel Beaufort Sea (DENMARK) Island Barrow Victoria Bay Tiksi Island Baffin Jan Mayen Norwegian Pevek Chukchi Island (NORWAY) Noril'sk Sea Murmansk Cherskiy Sea Arctic Circle (66°33') Arctic Circle (66°33') NORWAY Nuuk White Sea Fairbanks Great S Anadyr' ICELAND Nome U. S. (Godthåb) S I B E R I A Provideniya Bear Lake SWEDEN N Iqaluit Denmark Arkhangel'sk Mt.Mt. McKinleyMcKinley I Davis Strait Reykjavík Faroe (highest(highest pointpoint iinn A Islands FINLAND Lake NorthNorth America,America, 61946194 m)m) Strait Gulf T Yakutsk (DEN.) Ladoga R U S S I A Anchorage of Lake N Tórshavn Whitehorse Great Bothnia Onega U Slave Lake Hudson Oslo Helsinki O Magadan 60 60 Saint Petersburg Bay Stockholm Tallinn M Gulf of Alaska Churchill Rockall EST. Perm' Juneau R Baltic Yaroslavl' Bering Sea Kuujjuaq Labrador (U.K.) Nizhniy Tyumen' Fort McMurray Sea Riga¯ Izhevsk O North LAT. Novgorod Tomsk Sea Glasgow DENMARK Moscow Kazan' Yekaterinburg Krasnoyarsk LITH. -

Dusan Lajovic(Srb)

DUSAN LAJOVIC (SRB) www.dusan-lajovic.com @Dutzee Dusan Lajovic Official @dutzee Date of Birth: June 30, 1990 Career Win-Loss: 57-77 Birthplace: Belgrade, Serbia Career Win-Loss vs. Top 10: 0-6 Residence: Stara Pazova, Serbia Career 5-set Record: 1-5 Height: 1.83m (6’0”) Career Prize Money: $1,731,546 Weight: 78kg (172lbs) Highest Emirates ATP Ranking: Plays: Right-handed 57 (October 27, 2014) One-handed backhand Highest Emirates ATP Doubles Ranking: 104 (June 8, 2015) EMIRATES ATP RANKING HISTORY (W-L) Nishikori in 2R). Also won 1R matches at 2014 2016: 93 (19-23) 2012: 164 (2-1) 2008: 1093 (0-0) Wimbledon (d. Garcia-Lopez in 5 sets, l. to Kubot), 2015 Roland Garros (d. M. Gonzalez, l. to eventual champion 2015: 76 (17-21) 2011: 191 (3-5) 2007: T1461 (0-0) Wawrinka), 2016 Australian Open (d. Querrey, l. to 2014: 2010: 69 (16-19) 428 (0-2) Bautista Agut in 5 sets) and 2016 Roland Garros (d. 2013: 117 (0-6) 2009: 570 (0-0) Kudla, l. to Troicki). > ATP Masters 1000: After qualifying at 2014 Indian Wells 2016 HIGHLIGHTS (l. to Rosol in 1R), earned 1st ATP Masters 1000 win at Prize Money: $511,994 2014 Miami as LL (d. Lu, l. to Dolgopolov 76 in 3rd). Win-Loss: 19-23 (singles), 5-10 (doubles) Qualified at 2015 Rome (l. to Monaco in 1R) and 2015 Challenger: 4-2 (singles) Paris (d. Mahut, l. to Goffin in 2R). Also reached 2R at Singles Semi-finalist: São Paulo, Kitzbühel, Los Cabos 2016 Miami (d. -

Commencement

Commencement May 2016 Iowa City, Iowa Cover Design: The cover design represents the gold and topaz medallion worn by The University of Iowa president at formal academic ceremonies on campus. The medallion was designed and made by Karen Cantine as part of the work for her M.A. conferred August 4, 1965. 2 The University of Iowa Commencement Ceremonies Thursday, May 12, 2016 Pharmacy Coralville Marriott Hotel & Conference Center 10:00 a.m. Friday, May 13, 2016 School of Management Coralville Marriott Hotel & Conference Center 10:00 a.m. Law Iowa Memorial Union Main Lounge 12:00 p.m. Medicine Coralville Marriott Hotel & Conference Center 6:30 p.m. Graduate College Carver-Hawkeye Arena 7:00 p.m. Saturday May 14, 2016 Liberal Arts and Sciences Carver-Hawkeye Arena 9:00 a.m. Engineering Coralville Marriott Hotel & Conference Center 10:00 a.m. Nursing Iowa Memorial Union Main Lounge 10:00 a.m. Liberal Arts and Sciences Carver-Hawkeye Arena 1:00 p.m. Business Carver-Hawkeye Arena 5:00 p.m. 3 4 Table of Contents University Leaders ...............................................................................................................................................................7 Graduate College Ceremony - Order of Events, Friday, May 13, 2016 .......................................................................8 College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and University College 9:00 a.m. Ceremony - Order of Events, Saturday, May 14, 2016 ......................................................................................................................................................10 -

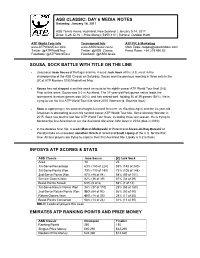

Sousa, Sock Battle with Title on the Line Infosys Atp

ASB CLASSIC: DAY 6 MEDIA NOTES Saturday, January 14, 2017 ASB Tennis Arena, Auckland, New Zealand | January 9-14, 2017 Draw: S-28, D-16 | Prize Money: $450,110 | Surface: Outdoor Hard ATP World Tour Info Tournament Info ATP PR & Marketing www.ATPWorldTour.com www.ASBClassic.co.nz Mark Epps: [email protected] Twitter: @ATPWorldTour Twitter: @ASB_Classic Press Room: +64 219 450 82 Facebook: @ATPWorldTour Facebook: @ASBClassic SOUSA, SOCK BATTLE WITH TITLE ON THE LINE Unseeded Joao Sousa of Portugal and No. 4 seed Jack Sock of the U.S. meet in the championship of the ASB Classic on Saturday. Sousa won the previous meeting in three sets in the 3R at ATP Masters 1000 Madrid last May. Sousa has not dropped a set this week en route to his eighth career ATP World Tour final (2-5). Prior to this week, Sousa was 0-2 in Auckland. The 27-year-old Portuguese native leads the tournament in return games won (40%) and has served well, holding 36 of 39 games (92%). He is trying to win his first ATP World Tour title since 2015 Valencia (d. Bautista Agut). Sock is appearing in his second straight Auckland final (ret. vs. Bautista Agut) and the 24-year-old American is attempting to earn his second career ATP World Tour title. Since winning Houston in 2015, Sock has lost his last four ATP World Tour finals, including three last season. He is trying to become the first American to win the Auckland title since John Isner in 2014 (also in 2010). In the doubles final, No. -

Results 16/10/2018 Page 1

Results 16/10/2018 Page 1 AFRICA CUP OF NATIONS ATP ANTWERP, BELGIUM 13:30 101 Madagaskar Eq. Guinea 1 : 0 1 : 0 13:30 2004 Simon G. Stakhovsky S. 6 : 0 2 : 0 14:00 102 Comoros Morocco 1 : 0 2 : 2 18:30 2005 Tsonga J-W. Pella G. 7 : 5 2 : 1 14:30 103 Malawi Cameroon 0 : 0 0 : 0 20:20 2006 Monfils G. Bemelmans R. 6 : 0 2 : 0 15:00 104 Burundi Mali 1 : 0 1 : 1 ATP MOSCOW, RUSSIA 15:00 105 Eswatini Egypt 0 : 1 0 : 2 15:00 106 South Sudan Gabon 0 : 0 0 : 1 10:00 2007 Dzumhur D. Gerasimov E. 1 : 6 1 : 2 15:30 107 Rwanda Guinea 0 : 1 1 : 1 11:30 2009 Kukushkin M. Donskoy E. 4 : 6 0 : 2 15:30 108 Seychelles South Africa 0 : 0 0 : 0 13:00 2010 Jaziri M. Basic M. 6 : 7 0 : 2 16:00 109 CAF Republic Ivory Coast 0 : 0 0 : 0 13:30 2011 Paire B. Zverev M. 7 : 6 2 : 1 16:00 110 Tanzania Cape Verde 1 : 0 2 : 0 14:30 2012 Lajovic D. Horansky F. 6 : 4 2 : 1 17:00 111 Benin Algeria 1 : 0 1 : 0 15:00 2013 Klizan M. Seppi A. 1 : 6 0 : 2 17:00 112 Niger Tunisia 1 : 2 1 : 2 17:30 2014 Kyrgios N. Rublev A. 6 : 3 2 : 1 18:00 113 Lesotho Uganda 0 : 2 0 : 2 ATP STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN 18:30 114 Gambia Togo 0 : 0 0 : 1 19:00 115 Botswana Burkina Faso 0 : 0 0 : 0 12:00 2015 Chung H. -

Sbi Po / Clerk 2019 Capsule

SBI PO / CLERK 2019 CAPSULE Exclusively prepared for RACE students PAGE : 64 | | PRICE : NOT FOR SALE (JANUARY-JUNE 2019) TOPIC : SBI PO / CLERK CAPSULE SBI PO/CLERK 2019 CAPSULE (JANUARY – JUNE 2019) INDEX TOPIC Page No BANKING & FINANCIAL AWARENESS 2 LIST OF INDEXES BY VARIOUS ORGANISATIONS 7 GDP FORECAST OF INDIA BY VARIOUS ORGANISATION 8 RANKINGS / REPORTS BY VARIOUS ORGANISATIONS 8 LIST OF VARIOUS COMMITTEE & ITS HEAD 11 LOAN SANCTIONED BY NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL BANKS TO INDIA 12 PENALITY IMPOSED BY RBI TO VARIOUS BANKS IN INDIA 13 LIST OF ACQUISTION & MERGER TOOK PLACE FROM JAN – JUNE 2019 13 APPS/SCHEMES/FACILITY LAUNCHED BY VARIOUS BANKS/ORGANISATIONS/COMPANY 13 NATIONAL NEWS 15 STATE NEWS 20 IIT’S IN NEWS 26 NATIONAL SUMMITS 26 INTERNATIONAL NEWS 30 INTERNATIONAL SUMMITS 34 LIST OF AGREEMENTS/MOU’S SIGNED BY INDIA WITH VARIOUS COUNTRIES 37 APPOINTMENTS / RESIGNATION /RETIREMENT / BRAND AMBASSADORS 38 AWARDS & HONOURS 41 BOOKS & AUTHORS 48 SPORTS NEWS 48 IMPORTANT EVENTS OF THE DAY 57 OBITUARY 60 CABINET MINISTERS 2019 / LIST OF MINISTERS OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE)/ LIST OF 61 MINISTERS OF STATE INTERIM BUDGET 2019-20 62 ________________________________________________________ RACE Coaching Institute for Banking and Government Jobs 7601808080 / 9043303030 www. RACEInstitute. in Courses Offered : BANK | SSC | RRB | TNPSC |KPSC | SBI PO & CLERK 2019 CAPSULE | 2 BANKING & FINANCIAL AWARENESS framework allowing them to resume their normal lending activities subject RBI IN NEWS to certain conditions and continuous monitoring. ➢ Second Bi-monthly Monetary Policy Statement, 2019-20 Resolution ➢ The Reserve Bank has imposed monetary penalty of two million rupees of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) Reserve Bank of India. -

GLOBAL HISTORY and NEW POLYCENTRIC APPROACHES Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System Palgrave Studies in Comparative Global History

Foreword by Patrick O’Brien Edited by Manuel Perez Garcia · Lucio De Sousa GLOBAL HISTORY AND NEW POLYCENTRIC APPROACHES Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System Palgrave Studies in Comparative Global History Series Editors Manuel Perez Garcia Shanghai Jiao Tong University Shanghai, China Lucio De Sousa Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Tokyo, Japan This series proposes a new geography of Global History research using Asian and Western sources, welcoming quality research and engag- ing outstanding scholarship from China, Europe and the Americas. Promoting academic excellence and critical intellectual analysis, it offers a rich source of global history research in sub-continental areas of Europe, Asia (notably China, Japan and the Philippines) and the Americas and aims to help understand the divergences and convergences between East and West. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15711 Manuel Perez Garcia · Lucio De Sousa Editors Global History and New Polycentric Approaches Europe, Asia and the Americas in a World Network System Editors Manuel Perez Garcia Lucio De Sousa Shanghai Jiao Tong University Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Shanghai, China Fuchu, Tokyo, Japan Pablo de Olavide University Seville, Spain Palgrave Studies in Comparative Global History ISBN 978-981-10-4052-8 ISBN 978-981-10-4053-5 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4053-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017937489 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

Annual Analyses of the EU Air Transport Market 2011

Annual Analyses of the EU Air Transport Market 2011 Final Report January 2013 European Commission Annual304243 Analyses ITD ITA of1E the EU Annual Analyses of the EU Air Transport Market - Final Air Transport Market25 January 2011 2013 Final Report January 2013 European Commission Disclaimer and copyright: This report has been carried out for the Directorate General for Mobility and Transport in the European Commission and expresses the opinion of the organisation undertaking the contract MOVE/E1/5-2010/SI2.579402. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the European Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the European Commission's or the Mobility and Energy DG's views. The European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the information given in the report, nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. Copyright in this report is held by the European Communities. Persons wishing to use the contents of this report (in whole or in part) for purposes other than their personal use are invited to submit a written request to the following address :European Commission - DG MOVE - Library (DM28, 0/36) - B-1049 Brussels e-mail (http://ec.europa.eu/transport/contact/index_en.htm) Mott MacDonald, Mott MacDonald House, 8-10 Sydenham Road, Croydon CR0 2EE, United Kingdom t +44 (0)20 8774 2000 f +44 (0)20 8681 5706, W www.mottmac.com Annual Analyses of the EU Air Transport Market 2011 Issue and revision record Revision Date Originator Checker Approver Description A 29 Feb 2012 A. Knight C.