9783039119950 Intro 002.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries Atlas of Whether used as a scholarly introduction into Eastern Christian monasticism or researcher’s directory or a travel guide, Alexei Krindatch brings together a fascinating collection of articles, facts, and statistics to comprehensively describe Orthodox Christian Monasteries in the United States. The careful examina- Atlas of American Orthodox tion of the key features of Orthodox monasteries provides solid academic frame for this book. With enticing verbal and photographic renderings, twenty-three Orthodox monastic communities scattered throughout the United States are brought to life for the reader. This is an essential book for anyone seeking to sample, explore or just better understand Orthodox Christian monastic life. Christian Monasteries Scott Thumma, Ph.D. Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research A truly delightful insight into Orthodox monasticism in the United States. The chapters on the history and tradition of Orthodox monasticism are carefully written to provide the reader with a solid theological understanding. They are then followed by a very human and personal description of the individual US Orthodox monasteries. A good resource for scholars, but also an excellent ‘tour guide’ for those seeking a more personal and intimate experience of monasticism. Thomas Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Executive Director Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) This is a fascinating and comprehensive guide to a small but important sector of American religious life. Whether you want to know about the history and theology of Orthodox monasticism or you just want to know what to expect if you visit, the stories, maps, and directories here are invaluable. -

Maxi-Catalogue 2014 Maxi-Catalogue 2014

maxi-catalogue 2014 maxi-catalogue 2014 New publications coming from Alexander Press: 1. Διερχόμενοι διά τού Ναού [Passing Through the Nave], by Dimitris Mavropoulos. 2. Εορτολογικά Παλινωδούμενα by Christos Yannaras. 3. SYNAXIS, The Second Anthology, 2002–2014. 4. Living Orthodoxy, 2nd edition, by Paul Ladouceur. 5. Rencontre avec λ’οrthodoxie, 2e édition, par Paul Ladouceur. 2 Alexander Press Philip Owen Arnould Sherrard CELEBR ATING . (23 September 1922 – 30 May 1995 Philip Sherrard Philip Sherrard was born in Oxford, educated at Cambridge and London, and taught at the universities of both Oxford and London, but made Greece his permanent home. A pioneer of modern Greek studies and translator, with Edmund Keeley, of Greece’s major modern poets, he wrote many books on Greek, Orthodox, philosophical and literary themes. With the Greek East G. E. H. Palmer and Bishop Kallistos Ware, he was and the also translator and editor of The Philokalia, the revered Latin West compilation of Orthodox spiritual texts from the 4th to a study in the christian tradition 15th centuries. by Philip Sherrard A profound, committed and imaginative thinker, his The division of Christendom into the Greek East theological and metaphysical writings covered issues and the Latin West has its origins far back in history but its from the division of Christendom into the Greek East consequences still affect western civilization. Sherrard seeks and Latin West, to the sacredness of man and nature and to indicate both the fundamental character and some of the the restoration of a sacred cosmology which he saw as consequences of this division. He points especially to the the only way to escape from the spiritual and ecological underlying metaphysical bases of Greek Christian thought, and contrasts them with those of the Latin West; he argues dereliction of the modern world. -

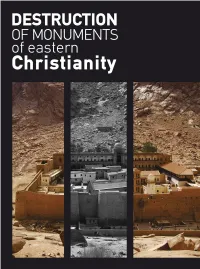

Monuments.Pdf

© 2017 INTERPARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY ON ORTHODOXY ISBN 978-960-560 -139 -3 Front cover page photo Sacred Monastery of Mount Sinai, Egypt Back cover page photo Saint Sophia’s Cathedral, Kiev, Ukrania Cover design Aristotelis Patrikarakos Book artwork Panagiotis Zevgolis, Graphic Designer, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Editing George Parissis, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | International Affairs Directorate Maria Bakali, I.A.O. Secretariat Lily Vardanyan, I.A.O. Secretariat Printing - Bookbinding HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Οι πληροφορίες των κειμένων παρέχονται από τους ίδιους τους διαγωνιζόμενους και όχι από άλλες πηγές The information of texts is provided by contestants themselves and not from other sources ΠΡΟΛΟΓΟΣ Η προστασία της παγκόσμιας πολιτιστικής κληρονομιάς, υποδηλώνει την υψηλή ευθύνη της κάθε κρατικής οντότητας προς τον πολιτισμό αλλά και ενδυναμώνει τα χαρακτηριστικά της έννοιας “πολίτης του κόσμου” σε κάθε σύγχρονο άνθρωπο. Η προστασία των θρησκευτικών μνημείων, υποδηλώνει επί πλέον σεβασμό στον Θεό, μετοχή στον ανθρώ - πινο πόνο και ενθάρρυνση της ανθρώπινης χαράς και ελπίδας. Μέσα σε κάθε θρησκευτικό μνημείο, περι - τοιχίζεται η ανθρώπινη οδύνη αιώνων, ο φόβος, η προσευχή και η παράκληση των πονεμένων και αδικημένων της ιστορίας του κόσμου αλλά και ο ύμνος, η ευχαριστία και η δοξολογία προς τον Δημιουργό. Σεβασμός προς το θρησκευτικό μνημείο, υποδηλώνει σεβασμό προς τα συσσωρευμένα από αιώνες αν - θρώπινα συναισθήματα. Βασισμένη σε αυτές τις απλές σκέψεις προχώρησε η Διεθνής Γραμματεία της Διακοινοβουλευτικής Συνέ - λευσης Ορθοδοξίας (Δ.Σ.Ο.) μετά από απόφαση της Γενικής της Συνέλευσης στην προκήρυξη του δεύτερου φωτογραφικού διαγωνισμού, με θέμα: « Καταστροφή των μνημείων της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής ». Επι πλέον, η βούληση της Δ.Σ.Ο., εστιάζεται στην πρόθεσή της να παρουσιάσει στο παγκόσμιο κοινό, τον πολιτισμικό αυτό θησαυρό της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής και να επισημάνει την ανάγκη μεγαλύτερης και ου - σιαστικότερης προστασίας του. -

Preserving & Promoting Understanding of the Monastic

We invite you to help the MOUNT ATHOS Preserving & Promoting FOUNDATION OF AMERICA Understanding of the in its efforts. Monastic Communities You can share in this effort in two ways: of Mount Athos 1. DONATE As a 501(c)(3), MAFA enables American taxpayers to make tax-deductible gifts and bequests that will help build an endowment to support the Holy Mountain. 2. PARTICIPATE Become part of our larger community of patrons, donors, and volunteers. Become a Patron, OUr Mission Donor, or Volunteer! www.mountathosfoundation.org MAFA aims to advance an understanding of, and provide benefit to, the monastic community DONATIONS BY MAIL OR ONLINE of Mount Athos, located in northeastern Please make checks payable to: Greece, in a variety of ways: Mount Athos Foundation of America • and RESTORATION PRESERVATION Mount Athos Foundation of America of historic monuments and artifacts ATTN: Roger McHaney, Treasurer • FOSTERING knowledge and study of the 2810 Kelly Drive monastic communities Manhattan, KS 66502 • SUPPORTING the operations of the 20 www.mountathosfoundation.org/giving monasteries and their dependencies in times Questions contact us at of need [email protected] To carry out this mission, MAFA works cooperatively with the Athonite Community as well as with organizations and foundations in the United States and abroad. To succeed in our mission, we depend on our patrons, donors, and volunteers. Thank You for Your Support The Holy Mountain For more than 1,000 years, Mount Athos has existed as the principal pan-Orthodox, multinational center of monasticism. Athos is unique within contemporary Europe as a self- governing region claiming the world’s oldest continuously existing democracy and entirely devoted to monastic life. -

An Essay in Universal History

AN ESSAY IN UNIVERSAL HISTORY From an Orthodox Christian Point of View VOLUME VI: THE AGE OF MAMMON (1945 to 1992) PART 2: from 1971 to 1992 Vladimir Moss © Copyright Vladimir Moss, 2018: All Rights Reserved 1 The main mark of modern governments is that we do not know who governs, de facto any more than de jure. We see the politician and not his backer; still less the backer of the backer; or, what is most important of all, the banker of the backer. J.R.R. Tolkien. It is time, it is the twelfth hour, for certain of our ecclesiastical representatives to stop being exclusively slaves of nationalism and politics, no matter what and whose, and become high priests and priests of the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church. Fr. Justin Popovich. The average person might well be no happier today than in 1800. We can choose our spouses, friends and neighbours, but they can choose to leave us. With the individual wielding unprecedented power to decide her own path in life, we find it ever harder to make commitments. We thus live in an increasingly lonely world of unravelling commitments and families. Yuval Noah Harari, (2014). The time will come when they will not endure sound doctrine, but according to their own desires, because they have itching ears, will heap up for themselves teachers, and they will turn their ears away from the truth, and be turned aside to fables. II Timothy 4.3-4. People have moved away from ‘religion’ as something anchored in organized worship and systematic beliefs within an institution, to a self-made ‘spirituality’ outside formal structures, which is based on experience, has no doctrine and makes no claim to philosophical coherence. -

Athos Gregory Ch

8 Athos Gregory Ch. 6_Athos Gregory Ch. 6 5/15/14 12:53 PM Page 154 TWENTIETH-CENTURY ATHOS it of course came the first motorized vehicles ever seen on Athos. 2 Such con - cessions to modernization were deeply shocking to many of the monks. And they were right to suspect that the trend would not stop there. SEEDS Of RENEWAl Numbers of monks continued to fall throughout the 960s and it was only in the early 970s that the trend was finally arrested. In 972 the population rose from ,5 to ,6—not a spectacular increase, but nevertheless the first to be recorded since the turn of the century. Until the end of the century the upturn was maintained in most years and the official total in 2000 stood at just over ,600. The following table shows the numbers for each monastery includ - ing novices and those living in the dependencies: Monastery 972 976 97 90 92 96 9 990 992 2000 lavra 0 55 25 26 29 09 7 5 62 Vatopedi 7 65 60 5 50 55 50 75 2 Iviron 5 6 52 52 5 5 5 6 6 7 Chilandar 57 6 69 52 5 6 60 75 Dionysiou 2 7 5 5 56 59 59 59 50 5 Koutloumousiou 6 6 66 57 0 75 7 7 77 95 Pantokrator 0 7 6 6 62 69 57 66 50 70 Xeropotamou 0 26 22 7 6 7 0 0 Zographou 2 9 6 2 5 20 Dochiariou 2 29 2 2 27 Karakalou 2 6 20 6 6 9 26 7 Philotheou 2 0 6 66 79 2 79 7 70 Simonopetra 2 59 6 60 72 79 7 0 7 7 St Paul’s 95 9 7 7 6 5 9 5 0 Stavronikita 7 5 0 0 0 2 5 Xenophontos 7 26 9 6 7 50 57 6 Grigoriou 22 0 57 6 7 62 72 70 77 6 Esphigmenou 9 5 0 2 56 0 Panteleimonos 22 29 0 0 2 2 5 0 5 Konstamonitou 6 7 6 22 29 20 26 0 27 26 Total ,6 ,206 ,27 ,9 ,275 ,25 ,255 ,290 ,7 ,60 These figures tell us a great deal about the revival and we shall examine 2 When Constantine Cavarnos visited Chilandar in 95, however, he was informed by fr Domitian, ‘We now have a tractor, too. -

CFHB 26 Manuel II Palaeologus Funeral Oration.Pdf

MANUEL PALAEOLOGUS FUNERAL ORATION CORPUS FONTIUM HISTORI-AE BYZANTINAE CONSILIO SOCIETATIS INTERNATIONAL IS STUD lIS BYZANTINIS PROVEHENDIS DESTINATAE EDITUM VOLUMEN XXVI MANUEL 11 PALAEOLOGUS FUNERAL ORATION ON HIS BROTHER THEODORE EDIDIT, ANGLlCE VERTlT ET ADNOTAVIT JULIANA CHRYSOSTOMIDES SERIES THESSALONICENSIS EDlDIT IOHANNES KARAYANNOPULOS APUD SOCIETATEM STUDIORUM BYZANTINORUM THESSALONICAE MCMLXXXV MANUEL 11 PALAEOLOGUS FUNERAL ORATION ON HIS BROTHER THEODORE INTRODUCTION, TEXT, TRANSLATION AND NOTES BY J. CHRYSOSTOMIDES ASSOCIATION FOR BYZANTINE RESEARCH THESSALONlKE 1985 l:TOIXEI00El:IA - EKTynnl:H 0ANAl:Hl: AATIN�ZHl:, E0N. AMYNHl: 38, THA. 221.529, 0El:l:AAONIKH ElL ANAMNHLIN n. Raymond-J. Loenertz a.p. NIKOAdov dJeJ..rpov Kai l1'7rpOC; TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations ........................................... ix-xii List of Signs ................................................. xiii List of Illustrations ............................................ xiv Foreword ................................." ... ................. 3-4 Introduction ..........' ....." ......................... ....... 5-62 I. The Author ............................................... 5-13 n. Historical Introduction ..................................... 15-25 'nl. Text and Manuscripts ..................................... 27-62 A. Text ................................................... 27-31 B. Manuscripts ............................................. 32-42 . C. Relationship of the Manuscripts ......................... 43-53 D. Editions and Translations -

Managing-The-Heritage-Of-Mt-Athos

174 Managing the heritage of Mt Athos Thymio Papayannis1 Introduction Cypriot monastic communities (Tachi- aios, 2006). Yet all the monks on Mt The spiritual, cultural and natural herit- Athos are recognised as citizens of age of Mt Athos dates back to the end Greece residing in a self-governed part of the first millennium AD, through ten of the country (Kadas, 2002). centuries of uninterrupted monastic life, and is still vibrant in the beginning of Already in 885 Emperor Basil I de- the third millennium. The twenty Chris- clared Mt Athos as ‘…a place of monks, tian Orthodox sacred monasteries that where no laymen nor farmers nor cat- share the Athonite peninsula – in tle-breeders were allowed to settle’. Halkidiki to the East of Thessaloniki – During the Byzantine Period a number are quite diverse. Established during of great monasteries were established the Byzantine times, and inspired by in the area. The time of prosperity for the monastic traditions of Eastern Chris- the monasteries continued even in the tianity, they have developed through the early Ottoman Empire period. However, ages in parallel paths and even have the heavy taxation gradually inflicted different ethnic backgrounds with on them led to an economic crisis dur- Greek, Russian, Serbian, Bulgarian and 1 The views included in this paper are of its au- thor and do not represent necessarily those of < The approach to the Stavronikita Monastery. the Holy Community of Mt Athos. 175 Cape Arapis younger and well-educated monks (Si- deropoulos, 2000) whose number has Chilandariou been doubled during the past forty Esgmenou Ouranoupoli Cape Agios Theodori years. -

Saints and Their Families in Byzantine Art

Saints and their Families in Byzantine Art Lois DREWER Δελτίον XAE 16 (1991-1992), Περίοδος Δ'. Στη μνήμη του André Grabar (1896-1990)• Σελ. 259-270 ΑΘΗΝΑ 1992 Lois Drewer SAINTS AND THEIR FAMILIES IN BYZANTINE ART* In recent studies Dorothy Abrahamse and Evelyne Pat- St. George rides over the sea to Mytilene on a white lagean, among others, have explored Greek hagiogra- horse with a young boy, still holding the glass of wine he phical texts for insight into Byzantine attitudes toward was serving when he was rescued, seated behind him. children and family life. In contrast, art historians have On a Mt. Sinai icon, St. Nicholas returns a similarly so far contributed relatively little to the debate1. The reasons for this are not hard to discover. Despite the overwhelming impact of the cult of saints in Byzantine * This article contains material presented, in different form, in papers art, narrative scenes depicting the lives of the saints are read at Parents and Children in the Middle Ages: An Interdisciplinary relatively rate. Furthermore, many of the existing hagi- Conference, held at the CUNY Graduate Center, New York City, on ographical scenes record the heroic suffering of the mar March 2, 1990, and at the Seventeenth Byzantine Studies Conference, tyrs in a seemingly unrelieved sequence of tortures and Hellenic College, Brookline, Mass., Nov. 7-10, 1991. 2 1. E. Patlagean, L'enfant et son avenir dans la famille byzantine executions . Other Byzantine representations of saints (IVème-XIIème siècles), in Structure sociale, famille, chrétienté à By- celebrate the values of the ascetic life including with zance, IVe-XIe siècles, London 1981, X, pp. -

Works of Athonite Icon Painters in Bulgaria (1750-1850)

INSTITUTE OF ART STUDIES, BAS ALEXANDER KUYUMDZHIEV WORKS OF ATHONITE ICON PAINTERS IN BULGARIA (1750-1850) AUTHOR SUMMARY OF A THESIS PAPER FOR OBTAINING A DSc DEGREE Sofia 2021 INSTITUTE OF ART STUDIES, BAS ALEXANDER KUYUMDZHIEV WORKS OF ATHONITE ICON PAINTERS IN BULGARIA (1750-1850) AUTHOR SUMMARY OF A THESIS PAPER FOR OBTAINING A DSc DEGREE IN ART AND FINE ARTS, 8.1, THEORY OF ART REVIEWERS: ASSOC. PROF. BLAGOVESTA IVANOVA-TSOTSOVA, DSc PROF. ELENA POPOVA, DSc PROF. EMMANUEL MOUTAFOV, PhD Sofia 2021 2 The DSc thesis has been discussed and approved for public defense on a Medieval and National Revival Research Group meeting held on October 16, 2020 The DSc thesis consists of 371 pages: an introduction, 5 chapters, conclusion and illustrations` provenance, 1063 illustrations in the text and а bibliography of 309 Bulgarian, and 162 foreign titles. The public defense will be held on 16th March 2021, 11:00 am, at the Institute of Art Studies. Members of the scientific committee: Assoc. Prof. Angel Nikolov, PhD, Sofia University; Assoc. Prof. Blagovesta Ivanova- Tsotsova, DSc, VSU; Prof. Elena Popova, DSc, Institute of Art Studies – BAS; Prof. Emmanuel Moutafov, PhD, Institute of Art Studies – BAS; Prof. Ivan Biliarsky, DSc, Institute of Historical Studies – BAS; Corr. Mem. Prof. Ivanka Gergova DSc, Institute of Art Studies – BAS; Prof. Mariyana Tsibranska-Kostova, DSc, Institute for Bulgarian Language – BAS; Assoc. Prof. Ivan Vanev, PhD, Institute of Art Studies – BAS, substitute member; Prof. Konstantin Totev, DSc, National Archaeological Institute with Museum – BAS, substitute member. The materials are available to those who may be interested in the Administrative Services Department of the Institute of the Art Studies on 21 Krakra Str., Sofia. -

Mount Athos(Greece)

World Heritage 30 COM Patrimoine mondial Paris, 10 April / 10 avril 2006 Original: English / anglais Distribution limited / distribution limitée UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L'EDUCATION, LA SCIENCE ET LA CULTURE CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE CONVENTION CONCERNANT LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL, CULTUREL ET NATUREL WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE / COMITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL Thirtieth session / Trentième session Vilnius, Lithuania / Vilnius, Lituanie 08-16 July 2006 / 08-16 juillet 2006 Item 7 of the Provisional Agenda: State of conservation of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List. Point 7 de l’Ordre du jour provisoire: Etat de conservation de biens inscrits sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial. JOINT UNESCO/WHC-ICOMOS-IUCN EXPERT MISSION REPORT / RAPPORT DE MISSION CONJOINTE DES EXPERTS DE L’UNESCO/CPM, DE L’ICOMOS ET DE L’IUCN Mount Athos (Greece) (454) / Mont Athos (Grece) (454) 30 January – 3 February 2006/ 30 janvier – 3 février 2006 This mission report should be read in conjunction with Document: Ce rapport de mission doit être lu conjointement avec le document suivant: WHC-06/30.COM/7A WHC-06/30.COM/7A.Add WHC-06/30.COM/7B WHC-06/30.COM/7B.Add REPORT ON THE JOINT MISSION UNESCO – ICOMOS- IUCN TO MOUNT ATHOS, GREECE, FROM 30 JANUARY TO 3 FEBRUARY 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND LIST OF RECOMMENDATIONS 1 BACKGROUND TO THE MISSION o Inscription history o Inscription criteria -

The Patriarchate of Constantinople Again, at Least Nominally, Became Independent After World War I and the Rise of Modern, Secu

ORTHODOXY IN THE WORLD CONSTANTINOPLE. The Patriarchate of Constantinople again, at least nominally, became independent after World War I and the rise of modern, secular Turkey, although greatly reduced in size. At present the Patriarch's jurisdiction includes Turkey, the island of Crete and other islands in the Aegean, the Greeks and certain other national groups in the Dispersion (the Diaspora) in Europe, America, Australia, etc. as well as the monastic republic of Mt. Athos and the autonomous Church of Finland. The present position of the Patriarchate in Turkey is precarious, persecution still exists there, and only a few thousand Greek Orthodox still remain in Turkey. (A) MT. ATHOS. Located on a small peninsula jutting out into the Aegean Sea from the Greek mainland near Thessalonica, Mt. Athos is a monastic republic consisting of twenty ruling monasteries, the oldest (Great Lavra) dating to the beginning of the 11th Century, as well as numerous other settlements sketes, kellia, hermitages, etc. Of the twenty ruling monasteries, seventeen are Greek, one Russian, one Serbian, and one Bulgarian. (One, Iveron, was originally founded as a Georgian monastery, but now is Greek.) Perhaps 1,500 Monks are presently on the Mountain, a dramatic decline from the turn of the Century when, in 1903, for example, there were over 7,000 Monks there. This is due, in great part, to the halt of vocations from the Communist countries, as well as to a general decline in monastic vocations worldwide. However, there appears to be a revival of monastic life there, particularly at the monasteries of Simonopetra, Dionysiou, Grigoriou, Stavronikita, and Philotheou, and two Monks have shone as spiritual lights there in this Century - the Elder Silouan ( 1938) of St.