Allocative and Implementation Efficiency in HIV Prevention and Treatment for People Who Inject Drugs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suitcase Fusion 8 Getting Started

Copyright © 2014–2018 Celartem, Inc., doing business as Extensis. This document and the software described in it are copyrighted with all rights reserved. This document or the software described may not be copied, in whole or part, without the written consent of Extensis, except in the normal use of the software, or to make a backup copy of the software. This exception does not allow copies to be made for others. Licensed under U.S. patents issued and pending. Celartem, Extensis, LizardTech, MrSID, NetPublish, Portfolio, Portfolio Flow, Portfolio NetPublish, Portfolio Server, Suitcase Fusion, Type Server, TurboSync, TeamSync, and Universal Type Server are registered trademarks of Celartem, Inc. The Celartem logo, Extensis logos, LizardTech logos, Extensis Portfolio, Font Sense, Font Vault, FontLink, QuickComp, QuickFind, QuickMatch, QuickType, Suitcase, Suitcase Attaché, Universal Type, Universal Type Client, and Universal Type Core are trademarks of Celartem, Inc. Adobe, Acrobat, After Effects, Creative Cloud, Creative Suite, Illustrator, InCopy, InDesign, Photoshop, PostScript, Typekit and XMP are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. Apache Tika, Apache Tomcat and Tomcat are trademarks of the Apache Software Foundation. Apple, Bonjour, the Bonjour logo, Finder, iBooks, iPhone, Mac, the Mac logo, Mac OS, OS X, Safari, and TrueType are trademarks of Apple Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. macOS is a trademark of Apple Inc. App Store is a service mark of Apple Inc. IOS is a trademark or registered trademark of Cisco in the U.S. and other countries and is used under license. Elasticsearch is a trademark of Elasticsearch BV, registered in the U.S. -

AVENIR Family

An Introduction To The AVENIR Family By Stacey Chen O V E R V I E W l Avenir was designed by Adrian Frutiger. l The typeface was first released in 1988 with three weights, before being expanded to six weights. l In 2004, together with Akira Kobayashi, Frutiger reworked the Avenir family. l Avenir has now become a common font in web, print, and graphic design, etc. l Frutiger was born in Unterseen, Switzerland 1928. l At age 16, Frutiger was apprenticed as a compositor to a printer, while taking classes in woodcuts and drawing. l With his second wife, Frutiger had two daughters, who both experienced mental health problems and committed suicide as adolescents. l Frutiger spent most of his professional career working in Paris and living in France, returning to Switzerland later in life. A D R I A N F R U T I G E R l Charles Peignot of Deberny Et Peignot recruited Frutiger based on the quality of the wood- engraved illustrations of his essay. l Impressed by the success of Futura typeface, Peignot encouraged a new, geometric sans-serif type in competition. l Frutiger disliked the regimentation of Futura, and persuaded Peignot that the new sans-serif be based on the realist model. l In 1988, Frutiger completed the family Avenir. Frutiger intended the font to be a more human version of geometric sans-serif types popular in the 1930s, such as Erbar and Futura. A D R I A N F R U T I G E R “Avenir” = “Future” French English A V E N I R i s l Futura is a geometric sans-serif typeface designed in 1927 by Paul Renner. -

Choosing-A-Font-For-Legal-Briefs Copy

Choosing a Font for Legal Briefs MANY LAWYERS MISTAKENLY THINK that court rules require absorb and retain your message. them to submit briefs in Times New Roman. But most Of course, designing a better legal document involves a lot jurisdictions actually allow a wide variety of fonts. more than simply choosing the “right” font. But the simple California, for example, requires only that you use a font act of using a font other than Times New Roman can have a “essentially equivalent to” Courier, Times New Roman or noticeable (and positive) impact on your briefs. Arial. CRC 2.105. In other words, any monospaced, serif or So which font should you use instead? In an ideal world, sans serif font (just not something like Comic Sans or we would all purchase top-quality fonts that are designed Braggadocio). Other states, such as Oregon, don’t for our purpose (e.g., long-form text). But the reality is that mention fonts at all in their rules. See, e.g., UTCR 2.010. most of us are limited to the system fonts installed on our But even if court rules allow fonts other than Times New computers. Even in that limited set, however, there are Roman, why should lawyers bother to switch? Because Times better and worse options. Below is a list of system fonts that New Roman is actually a really bad typeface for legal briefs. It was I would recommend for legal briefs. To add some variety to designed for newspapers—that is, for small columns of tiny your document, try pairing two different fonts—a serif for text. -

Brand Guide 1 Contents

BRAND GUIDE 1 CONTENTS 3 Who We Are & Mission 10 Photography » Style Recommendations 4 Logo & Usage » Use of Stock Images 4 Our Logo 5 Area of Isolation 11 Copy 5 Size Recommendations 11 References in Copy 6 Palette Colors 11 Tagline 7 Background Usage 12 Brand Voice 7 Incorrect Background Usage 8 Incorrect Logo Usage 13 Key Messages 13 About the Organization 9 Typography 13 Community Investment » Primary Font 14 Community Engagement » System & Web Font 14 Community Stewardship 15 Glossary 2 The Partnership for Better Health is a community foundation that WHO WE ARE works collaboratively with local and regional organizations throughout parts of Cumberland, Perry, Adams and Franklin Counties to promote responsible health practices and enhance access to affordable, quality health care for all. Through community investment, engagement and good stewardship, we foster sustainable solutions to some of today’s toughest health challenges. We are making a difference — together. » OUR MISSION The Partnership for Better Health identifies and addresses health care needs and policies, promotes responsible health practices and enhances access to and delivery of health services. 3 LOGO & USAGE » OUR LOGO The Partnership for Better Health logo is an energetic, active mark designed to represent the collaborative spirit of the foundation. The overlapping “leaves” in our icon symbolize improvement in health and wellbeing, and call to the strength and vitality of trees — a symbol that our organization has historically embraced. The typography is clean, friendly and modern; the colors are approachable, bright and fresh. Marketing collateral should be designed with this essence in mind. a. The primary logo consists of the leaf icon, wordmark and tagline. -

Academic Poster Workshop

HOW TO MAKE AN ACADEMIC POSTER An Opinionated Tutorial Joey Stanley September 2019 WHY THIS WORKSHOP Potentially lots of firsts—scary! • The first time you’ve done a study from start to finish. • The first time you’ve created an academic poster. • The first time you’ve been to a conference. This workshop • I had no idea what I was doing too. • I want this to be the workshop I wish I had had my first time through. My experience • I’ve been to lots of conferences. • I’ve presented four posters. 2 THREE ASPECTS TO A POSTER PRESENTATION The Research The Poster The Presentation • Intro • Layout • Elevator pitches • (Data) • Visuals • Know your audience • Methods • Color • Stand-alone? • Results • Whitespace • Online distribution • Conclusion • Aesthetics THE RESEARCH RESEARCH Above all else, the research should be good! RESEARCH Picking a research topic • Think of a linguistic phenomenon you’re interested in. • If you’re not sure, think of a subfield or a language you like. • If you’re stuck, was there a term paper or homework assignment you really enjoyed? That you wish you could explore further if you had the time? A good research topic • Ideally it should be innovative, timely, and relevant, building upon the work of others by examining a gap in the literature that should be filled. • For an undergrad poster session, the stakes are pretty low. 6 OUTLINE OF YOUR RESEARCH 1. Introduction 3. Results • Brief review of literature. • The results of your analysis • Show the need for your study. • Ideally, with visualizations • Include citations • Your hypothesis 4. -

Avenir, the Future for Amsterdam

Avenir, the future for Amsterdam By Henk Gianotten, August 07th 2003, In recent decades the capital of the Netherlands has experienced both, rapid growth and the decentralization of its local government and all in a period when the expectations of its citizens and visitors were becoming more varied and demanding. With all these changes the city council and its allied services felt an increasing need for a unifying visual identity that would be inextricably bound to the culture of their organization. An identity flexible enough to represent the diverse services within the municipality, yet links each of these with the larger whole. This unifying style also needed to make a confident visual statement for use on printed material, packaging, clothing, website, and a fleet of city-owned vehicles. Certainly the search for this new and clearly defined “face” would be an almost impossible task to present to designers. Deciding on a new “visual identity” for non-profit and government organizations, then developing and maintaining it is an extremely difficult process, that is largely dependent on the components that make up the total identity. It is far easier to create a unified appearance for two hundred shoe stores than it is to create a visual style that links tens of distinctly different departments and services of one local authority. To fully appreciate the complexity of this image-change it is necessary to look at the history of Amsterdam. It has always been a very liberal city, and its municipal services, like its citizens, have evolved within a system long accustomed to a great diversity of opinionated “faces”. -

Use One Typeface

01 Flush Left When in doubt, set your type flush left rag right. Why? In western culture, people read from top to bottom, left to right. By justifying type left, the eye is able to find the edge and read copy much more easily. Avoid indenting the first line of a paragraph for this reason. Everything I learned in design school in 10 simple rules to help you start designing like a rock star. @theChrisDo www.TheFutur.com 02 Use One Typeface Using two typefaces successfully within a layout requires an understanding of the chosen faces in order to be confident that they are complementary. In general, avoid using two typefaces of the same classification. For example, do not use two sans serif, serif, slab serif or script faces together. The reason—contrast. Stay with one typeface until you have achieved mastery. Helvetica Neue Everything I learned in design school in 10 simple rules to help you start designing like a rock star. @theChrisDo www.TheFutur.com 03 Skip A Weight Go from light to bold, or from medium to extra bold when changing font weights. The key to great design is contrast. Slight changes in weight change make it harder for the audience to notice the difference. Try mixing bold for the headline and light for the body copy for greater contrast. Light/Bold Everything I learned in design school in 10 simple rules to help you start designing like a rock star. @theChrisDo www.TheFutur.com 04 Double Point Size A good rule of thumb when changing point sizes, is to double or half the point size you are using. -

Alisha Witty Typography Week 3 Avenir

Avenir, Typeface for the Future Avenir – futuristic modernly humanistic typeface Avenir is a geometric sans- A v e n i r w a s o r i g i n a l l y Sources serif typeface designed by released in 1988 with three I. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Avenir_(typeface) Adrian Frutiger in 1988 and weights, each with a roman II. http://www.digplanet.com/ r e l e a s e d b y L i n o t y p e and oblique version, and wiki/Avenir_(typeface) GmbH. The word avenir is used Frutiger's two-digit French for "future". The font w e i g h t a n d w i d t h i s d e r i v e d f ro m e a r l y convention for names: 45 g e o m e t r i c s a n s - s e r i f (book), 46 (book oblique), typefaces Erbar (1922), 55 (text weight), 56 (text designed by Jakob Erbar, weight oblique), (75)85 and Futura (1927), designed (heavy), and (76)86 (heavy by Paul Renner. Frutiger oblique). The typeface wished Avenir to be a more family was later expanded organically grown humanist to six weights, each with a interpretation of these roman and an oblique highly geometric types. version. The original release While similarities can be of Avenir has weights seen with Futura, the two- g r o u p e d v e r y c l o s e storey lowercase a is more together, with the difference like Erbar, and also recalls barely distinguishable. -

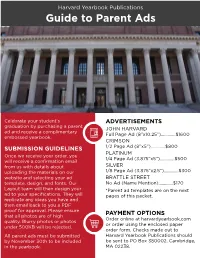

Parent Ad Style Guide

Harvard Yearbook Publications Guide to Parent Ads Celebrate your student’s ADVERTISEMENTS graduation by purchasing a parent JOHN HARVARD ad and receive a complimentary Full Page Ad (8”x10.25”).............$1600 embossed yearbook. CRIMSON SUBMISSION GUIDELINES 1/2 Page Ad (8”x5”).............$800 PLATINUM Once we receive your order, you 1/4 Page Ad (3.875”x5”).............$500 will receive a confirmation email from us with details about SILVER uploading the materials on our 1/8 Page Ad (3.875”x2.5”).............$300 website and selecting your ad BRATTLE STREET template, design, and fonts. Our No Ad (Name Mention).............$170 Layout team will then design your *Parent ad templates are on the next ad to your specifications. They will pages of this packet. replicate any ideas you have and then email back to you a PDF proof for approval. Please ensure that all photos are of high PAYMENT OPTIONS Order online at harvardyearbook.com quality. Blurry photos or photos or order using the enclosed paper under 500KB will be rejected. order form. Checks made out to All parent ads must be submitted Harvard Yearbook Publications should by November 30th to be included be sent to PO Box 380002, Cambridge, in the yearbook. MA 02238. ADVERTISEMENT SIZE: SILVER (1/8 PAGE) - 3.875 x 2.5 in. Layout: Silver #1 John Harvard Font: Times (Bold & Regular) Congratulations on all of your accomplishments! We are so very proud of you. Love, Mom, Dad, and Drew Layout: Silver #2 John Harvard Font: Arial (Bold & Regular) Congratulations on all of your accomplishments! We are so very proud of you. -

Alphabet Fonts

R Y MO Q BI KS LV A C U GX TDJH ZE NFW P Alphabet Fonts Coded by Guodu 60-212, Fall 2016 Professor Golan Levin Charter Roman A Adobe Devanagari Bold Bebas Neue Thin AA Lucida Fax Regular B Hiragino Kaku Gothic Std W8 STIXGeneral-Regular BB Onyx C Arial Narrow Bold Italic Avenir Light CC Imprint MT Shadow D Roboto Black Futura Condensed Medium DD *CP\K2GP6%$QNF Arial Unicode MS ' Adobe Caslon Pro EE Adobe Gurmukhi Bold Roboto Regular MrsEavesAllSmallCaps FFF Adobe Garamond Pro Bold Italic Cochin Italic Tekton Pro Bold Extended GG H Haettenschweiler H Bookman Old Style Italic Avenir Next Demi Bold Italic H Trebuchet MS Bold II Slim Joe Seravek Medium I Roboto Medium Italic J Bodoni 72 Book Italic Cambria Bold JJ Apple Chancery Roboto Light Italic Kozuka Gothic Pro R KKK Savoye LET Plain:1.0 . *CP\K2GP5%$QNF Seravek Light Italic LL Corbel Nueva Std Bold Condensed Italic M Orator Std Slanted MM MeninBlue Tekton Pro Bold Oblique N Superclarendon Light NN Minion Pro Bold Italic Kohinoor Devanagari Bold Avenir Next Condensed Ultra Light Italic OOO Book Antiqua Bold Italic Seravek ExtraLight Italic P Nanum Pen Script P Bukhari Script Songti SC Light Bebas Neue Thin QQQ Malayalam Sangam MN Roboto Bold Italic RR Menlo Bold R Frutiger LT Std 65 Bold OCR A Std Orator Std Medium SSS Courier New T Source Sans Pro TT U Times New Roman Italic Gill Sans SemiBold U RBNo2 Light U Bodoni 72 Oldstyle Book Italic Bell MT Italic V Palatino Bold Italic VV MS PMincho W MetaCondOT-ExtraBold Trajan Pro WW X MrsEavesRoman Regular X XX Century Hoefer Text Italic NanumMyeongjoExtraBold YYY Bukhari Script Century Schoolbook Italic Z Constantia Bold ZZ C U B H X P W M KF S L O I T V R J Y A Q G E D N. -

Futura (Typeface) 1 Futura (Typeface)

Futura (typeface) 1 Futura (typeface) Category Sans-serif Classification geometric sans-serif Designer(s) Paul Renner Edwin W. Shaar (Extra Bold, Extra Bold Italic) Tommy Thompson (Extra Bold Italic) Foundry Bauer Type Foundry Date created 1927 Re-issuing foundries Intertype Design based on Bauhaus In typography, Futura is a geometric sans-serif typeface designed in 1927[1] by Paul Renner. It is based on geometric shapes that became representative of visual elements of the Bauhaus design style of 1919–1933.[2] Commissioned by the Bauer Type Foundry, in reaction to Ludwig & Mayer's seminal Erbar of 1922, Futura was commercially released in 1936.[3] The family was originally cast in Light, Medium, Bold, and Bold Oblique fonts in 1928. Light Oblique, Medium Oblique, Demibold, and Demibold Oblique fonts were later released in 1930. Book font was released in 1932. Book Oblique font was released in 1939. Extra Bold font was designed by Edwin W. Shaar in 1952. Extra Bold Italic font was designed in 1955 by Edwin W. Shaar and Tommy Thompson. Matrices for machine composition were made by Intertype. Although Renner was not associated with the Bauhaus, he shared many of its idioms and believed that a modern typeface should express modern models, rather than be a revival of a previous design. Renner's initial design included several geometrically constructed alternative characters and ranging (old-style) figures, which can be found in the typeface Architype Renner. Futura has an appearance of efficiency and forwardness. The typeface is derived from simple geometric forms (near-perfect circles, triangles and squares) and is based on strokes of near-even weight, which are low in contrast. -

Allocative and Implementation Efficiency in HIV Prevention and Treatment for People Who Inject Drugs

International Journal of Drug Policy 38 (2016) 73–80 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Drug Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/drugpo Editors’ Choice Allocative and implementation efficiency in HIV prevention and treatment for people who inject drugs Clemens Benedikta,*, Sherrie L. Kellyb, David Wilsona, David P. Wilsonb, on behalf of the Optima Consortium a World Bank, Washington, DC, USA b Burnet Institute, Melbourne, Australia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Background: Estimated global new HIV infections among people who inject drugs (PWID) remained Received 19 July 2016 stable over the 2010–2015 period and the target of a 50% reduction over this period was missed. To Received in revised form 28 September 2016 achieve the 2020 UNAIDS target of reducing adult HIV infections by 75% compared to 2010, accelerated Accepted 19 October 2016 action in scaling up HIV programs for PWID is required. In a context of diminishing external support to HIV programs in countries where most HIV-affected PWID live, it is essential that available resources are Keywords: allocated and used as efficiently as possible. HIV Methods: Allocative and implementation efficiency analysis methods were applied. Optima, a dynamic, Allocative efficiency population-based HIV model with an integrated program and economic analysis framework was applied Implementation efficiency Mathematical modelling in eight countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA). Mathematical analyses established Optimization optimized allocations of resources. An implementation efficiency analysis focused on examining Harm reduction technical efficiency, unit costs, and heterogeneity of service delivery models and practices. Results: Findings from the latest reported data revealed that countries allocated between 4% (Bulgaria) and 40% (Georgia) of total HIV resources to programs targeting PWID — with a median of 13% for the eight countries.