Waveguides Waveguides, Like Transmission Lines, Are Structures Used to Guide Electromagnetic Waves from Point to Point. However

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RF Coils, Helical Resonators and Voltage Magnification by Coherent Spatial Modes

TELSIKS 2001, University of Nis, Yugoslavia (September 19-21, 2001) and MICROWAVE REVIEW 1 RF Coils, Helical Resonators and Voltage Magnification by Coherent Spatial Modes K.L. Corum* and J.F. Corum** “Is there, I ask, can there be, a more interesting study than that of alternating currents.” Nikola Tesla, (Life Fellow, and 1892 Vice President of the AIEE)1 Abstract – By modeling a wire-wound coil as an anisotropically II. CYLINDRICAL HELICES conducting cylindrical boundary, one may start from Maxwell’s equations and deduce the structure’s resonant behavior. Not A. Problem Formulation only can the propagation factor and characteristic impedance be determined for such a helically disposed surface waveguide, but also its resonances, “self-capacitance” (so-called), and its voltage A uniform helix is described by its radius (r = a), its pitch magnification by standing waves. Further, the Tesla coil passes (or turn-to-turn wire spacing "s"), and its pitch angle ψ, to a conventional lumped element inductor as the helix is which is the angle that the tangent to the helix makes with a electrically shortened. plane perpendicular to the axis of the structure (z). Geometrically, ψ = cot-1(2πa/s). The wave equation is not Keywords – coil, helix, surface wave, resonator, inductor, Tesla. separable in helical coordinates and there exists no rigorous 3 solution of Maxwell's equations for the solenoidal helix. I. INTRODUCTION However, at radio frequencies a wire-wound helix with many turns per free-space wavelength (e.g., a Tesla coil) One of the more significant challenges in electrical may be modeled as an idealized anisotropically conducting cylindrical surface that conducts only in the helical science is that of constricting a great deal of insulated conductor into a compact spatial volume and determining direction. -

Lecture 26 Dielectric Slab Waveguides

Lecture 26 Dielectric Slab Waveguides In this lecture you will learn: • Dielectric slab waveguides •TE and TM guided modes in dielectric slab waveguides ECE 303 – Fall 2005 – Farhan Rana – Cornell University TE Guided Modes in Parallel-Plate Metal Waveguides r E()rr = yˆ E sin()k x e− j kz z x>0 o x x Ei Ei r r Ey k E r k i r kr i H Hi i z ε µo Hr r r ki = −kx xˆ + kzzˆ kr = kx xˆ + kzzˆ Guided TE modes are TE-waves bouncing back and fourth between two metal plates and propagating in the z-direction ! The x-component of the wavevector can have only discrete values – its quantized m π k = where : m = 1, 2, 3, x d KK ECE 303 – Fall 2005 – Farhan Rana – Cornell University 1 Dielectric Waveguides - I Consider TE-wave undergoing total internal reflection: E i x ε1 µo r k E r i r kr H θ θ i i i z r H r ki = −kx xˆ + kzzˆ r kr = kx xˆ + kzzˆ Evanescent wave ε2 µo ε1 > ε2 r E()rr = yˆ E e− j ()−kx x +kz z + yˆ ΓE e− j (k x x +kz z) 2 2 2 x>0 i i kz + kx = ω µo ε1 Γ = 1 when θi > θc When θ i > θ c : kx = − jα x r E()rr = yˆ T E e− j kz z e−α x x 2 2 2 x<0 i kz − α x = ω µo ε2 ECE 303 – Fall 2005 – Farhan Rana – Cornell University Dielectric Waveguides - II x ε2 µo Evanescent wave cladding Ei E ε1 µo r i r k E r k i r kr i core Hi θi θi Hi ε1 > ε2 z Hr cladding Evanescent wave ε2 µo One can have a guided wave that is bouncing between two dielectric interfaces due to total internal reflection and moving in the z-direction ECE 303 – Fall 2005 – Farhan Rana – Cornell University 2 Dielectric Slab Waveguides W 2d Assumption: W >> d x cladding y core -

High Gain Slotted Waveguide Antenna Based on Beam Focusing Using Electrically Split Ring Resonator Metasurface Employing Negative Refractive Index Medium

Progress In Electromagnetics Research C, Vol. 79, 115–126, 2017 High Gain Slotted Waveguide Antenna Based on Beam Focusing Using Electrically Split Ring Resonator Metasurface Employing Negative Refractive Index Medium Adel A. A. Abdelrehim and Hooshang Ghafouri-Shiraz* Abstract—In this paper, a new high performance slotted waveguide antenna incorporated with negative refractive index metamaterial structure is proposed, designed and experimentally demonstrated. The metamaterial structure is constructed from a multilayer two-directional structure of electrically split ring resonator which exhibits negative refractive index in direction of the radiated wave propagation when it is placed in front of the slotted waveguide antenna. As a result, the radiation beams of the slotted waveguide antenna are focused in both E and H planes, and hence the directivity and the gain are improved, while the beam area is reduced. The proposed antenna and the metamaterial structure operating at 10 GHz are designed, optimized and numerically simulated by using CST software. The effective parameters of the eSRR structure are extracted by Nicolson Ross Weir (NRW) algorithm from the s-parameters. For experimental verification, a proposed antenna operating at 10 GHz is fabricated using both wet etching microwave integrated circuit technique (for the metamaterial structure) and milling technique (for the slotted waveguide antenna). The measurements are carried out in an anechoic chamber. The measured results show that the E plane gain of the proposed slotted waveguide antenna is improved from 6.5 dB to 11 dB as compared to the conventional slotted waveguide antenna. Also, the E plane beamwidth is reduced from 94.1 degrees to about 50 degrees. -

Waveguide Direction User Manual

WaveGuide Direction Ex. Certified User Manual WaveGuide Direction Ex. Certified User Manual Applicable for product no. WG-DR40-EX Related to software versions: wdr 4.#-# Version 4.0 21st of November 2016 Radac B.V. Elektronicaweg 16b 2628 XG Delft The Netherlands tel: +31(0)15 890 3203 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.radac.nl Preface This user manual and technical documentation is intended for engineers and technicians involved in the software and hardware setup of the Ex. certified version of the WaveGuide Direction. Note All connections to the instrument must be made with shielded cables with exception of the mains. The shielding must be grounded in the cable gland or in the terminal compartment on both ends of the cable. For more information regarding wiring and cable specifications, please refer to Chapter 2. Legal aspects The mechanical and electrical installation shall only be carried out by trained personnel with knowledge of the local requirements and regulations for installation of electronic equipment. The information in this installation guide is the copyright property of Radac BV. Radac BV disclaims any responsibility for personal injury or damage to equipment caused by: Deviation from any of the prescribed procedures. • Execution of activities that are not prescribed. • Neglect of the general safety precautions for handling tools and use of electricity. • The contents, descriptions and specifications in this installation guide are subject to change without notice. Radac BV accepts no responsibility for any errors that may appear in this user manual. Additional information Please do not hesitate to contact Radac or its representative if you require additional information. -

The Self-Resonance and Self-Capacitance of Solenoid Coils: Applicable Theory, Models and Calculation Methods

1 The self-resonance and self-capacitance of solenoid coils: applicable theory, models and calculation methods. By David W Knight1 Version2 1.00, 4th May 2016. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.1472.0887 Abstract The data on which Medhurst's semi-empirical self-capacitance formula is based are re-analysed in a way that takes the permittivity of the coil-former into account. The updated formula is compared with theories attributing self-capacitance to the capacitance between adjacent turns, and also with transmission-line theories. The inter-turn capacitance approach is found to have no predictive power. Transmission-line behaviour is corroborated by measurements using an induction loop and a receiving antenna, and by visualising the electric field using a gas discharge tube. In-circuit solenoid self-capacitance determinations show long-coil asymptotic behaviour corresponding to a wave propagating along the helical conductor with a phase-velocity governed by the local refractive index (i.e., v = c if the medium is air). This is consistent with measurements of transformer phase error vs. frequency, which indicate a constant time delay. These observations are at odds with the fact that a long solenoid in free space will exhibit helical propagation with a frequency-dependent phase velocity > c. The implication is that unmodified helical-waveguide theories are not appropriate for the prediction of self-capacitance, but they remain applicable in principle to open- circuit systems, such as Tesla coils, helical resonators and loaded vertical antennas, despite poor agreement with actual measurements. A semi-empirical method is given for predicting the first self- resonance frequencies of free coils by treating the coil as a helical transmission-line terminated by its own axial-field and fringe-field capacitances. -

Ec6503 - Transmission Lines and Waveguides Transmission Lines and Waveguides Unit I - Transmission Line Theory 1

EC6503 - TRANSMISSION LINES AND WAVEGUIDES TRANSMISSION LINES AND WAVEGUIDES UNIT I - TRANSMISSION LINE THEORY 1. Define – Characteristic Impedance [M/J–2006, N/D–2006] Characteristic impedance is defined as the impedance of a transmission line measured at the sending end. It is given by 푍 푍0 = √ ⁄푌 where Z = R + jωL is the series impedance Y = G + jωC is the shunt admittance 2. State the line parameters of a transmission line. The line parameters of a transmission line are resistance, inductance, capacitance and conductance. Resistance (R) is defined as the loop resistance per unit length of the transmission line. Its unit is ohms/km. Inductance (L) is defined as the loop inductance per unit length of the transmission line. Its unit is Henries/km. Capacitance (C) is defined as the shunt capacitance per unit length between the two transmission lines. Its unit is Farad/km. Conductance (G) is defined as the shunt conductance per unit length between the two transmission lines. Its unit is mhos/km. 3. What are the secondary constants of a line? The secondary constants of a line are 푍 i. Characteristic impedance, 푍0 = √ ⁄푌 ii. Propagation constant, γ = α + jβ 4. Why the line parameters are called distributed elements? The line parameters R, L, C and G are distributed over the entire length of the transmission line. Hence they are called distributed parameters. They are also called primary constants. The infinite line, wavelength, velocity, propagation & Distortion line, the telephone cable 5. What is an infinite line? [M/J–2012, A/M–2004] An infinite line is a line where length is infinite. -

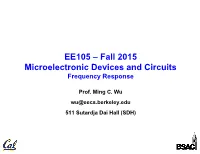

Frequency Response

EE105 – Fall 2015 Microelectronic Devices and Circuits Frequency Response Prof. Ming C. Wu [email protected] 511 Sutardja Dai Hall (SDH) Amplifier Frequency Response: Lower and Upper Cutoff Frequency • Midband gain Amid and upper and lower cutoff frequencies ωH and ω L that define bandwidth of an amplifier are often of more interest than the complete transferfunction • Coupling and bypass capacitors(~ F) determineω L • Transistor (and stray) capacitances(~ pF) determineω H Lower Cutoff Frequency (ωL) Approximation: Short-Circuit Time Constant (SCTC) Method 1. Identify all coupling and bypass capacitors 2. Pick one capacitor ( ) at a time, replace all others with short circuits 3. Replace independent voltage source withshort , and independent current source withopen 4. Calculate the resistance ( ) in parallel with 5. Calculate the time constant, 6. Repeat this for each of n the capacitor 7. The low cut-off frequency can be approximated by n 1 ωL ≅ ∑ i=1 RiSCi Note: this is an approximation. The real low cut-off is slightly lower Lower Cutoff Frequency (ωL) Using SCTC Method for CS Amplifier SCTC Method: 1 n 1 fL ≅ ∑ 2π i=1 RiSCi For the Common-Source Amplifier: 1 # 1 1 1 & fL ≅ % + + ( 2π $ R1SC1 R2SC2 R3SC3 ' Lower Cutoff Frequency (ωL) Using SCTC Method for CS Amplifier Using the SCTC method: For C2 : = + = + 1 " 1 1 1 % R3S R3 (RD RiD ) R3 (RD ro ) fL ≅ $ + + ' 2π # R1SC1 R2SC2 R3SC3 & For C1: R1S = RI +(RG RiG ) = RI + RG For C3 : 1 R2S = RS RiS = RS gm Design: How Do We Choose the Coupling and Bypass Capacitor Values? • Since the impedance of a capacitor increases with decreasing frequency, coupling/bypass capacitors reduce amplifier gain at low frequencies. -

Modal Propagation and Excitation on a Wire-Medium Slab

1112 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON MICROWAVE THEORY AND TECHNIQUES, VOL. 56, NO. 5, MAY 2008 Modal Propagation and Excitation on a Wire-Medium Slab Paolo Burghignoli, Senior Member, IEEE, Giampiero Lovat, Member, IEEE, Filippo Capolino, Senior Member, IEEE, David R. Jackson, Fellow, IEEE, and Donald R. Wilton, Life Fellow, IEEE Abstract—A grounded wire-medium slab has recently been shown to support leaky modes with azimuthally independent propagation wavenumbers capable of radiating directive omni- directional beams. In this paper, the analysis is generalized to wire-medium slabs in air, extending the omnidirectionality prop- erties to even modes, performing a parametric analysis of leaky modes by varying the geometrical parameters of the wire-medium lattice, and showing that, in the long-wavelength regime, surface modes cannot be excited at the interface between the air and wire medium. The electric field excited at the air/wire-medium interface by a horizontal electric dipole parallel to the wires is also studied by deriving the relevant Green’s function for the homogenized slab model. When the near field is dominated by a leaky mode, it is found to be azimuthally independent and almost perfectly linearly polarized. This result, which has not been previ- ously observed in any other leaky-wave structure for a single leaky mode, is validated through full-wave moment-method simulations of an actual wire-medium slab with a finite size. Index Terms—Leaky modes, metamaterials, near field, planar Fig. 1. (a) Wire-medium slab in air with the relevant coordinate axes. (b) Transverse view of the wire-medium slab with the relevant geometrical slab, wire medium. -

Instruction Manual Waveguide & Waveguide Server

Instruction manual WaveGuide & WaveGuide Server Radac bv Elektronicaweg 16b 2628 XG DELFT Phone: +31 15 890 32 03 Email: [email protected] www.radac.n l Instruction manual WaveGuide + WaveGuide Server Version 4.1 2 of 30 Oct 2013 Instruction manual WaveGuide + WaveGuide Server Version 4.1 3 of 30 Oct 2013 Instruction manual WaveGuide + WaveGuide Server Table of Contents Introduction...................................................................................................................................................................4 Installation.....................................................................................................................................................................5 The WaveGuide Sensor...........................................................................................................................................5 CaBling.....................................................................................................................................................................6 The WaveGuide Server............................................................................................................................................7 Commissioning the system...........................................................................................................................................9 Connect the WGS to a computer.............................................................................................................................9 Authorization.........................................................................................................................................................10 -

Analysis of a Waveguide-Fed Metasurface Antenna

Analysis of a Waveguide-Fed Metasurface Antenna Smith, D., Yurduseven, O., Mancera, L. P., Bowen, P., & Kundtz, N. B. (2017). Analysis of a Waveguide-Fed Metasurface Antenna. Physical Review Applied, 8(5). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.8.054048 Published in: Physical Review Applied Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2017 American Physical Society. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:02. Oct. 2021 PHYSICAL REVIEW APPLIED 8, 054048 (2017) Analysis of a Waveguide-Fed Metasurface Antenna † † David R. Smith,* Okan Yurduseven, Laura Pulido Mancera, and Patrick Bowen Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708, USA Nathan B. -

Feedback Amplifiers

UNIT II FEEDBACK AMPLIFIERS & OSCILLATORS FEEDBACK AMPLIFIERS: Feedback concept, types of feedback, Amplifier models: Voltage amplifier, current amplifier, trans-conductance amplifier and trans-resistance amplifier, feedback amplifier topologies, characteristics of negative feedback amplifiers, Analysis of feedback amplifiers, Performance comparison of feedback amplifiers. OSCILLATORS: Principle of operation, Barkhausen Criterion, types of oscillators, Analysis of RC-phase shift and Wien bridge oscillators using BJT, Generalized analysis of LC Oscillators, Hartley and Colpitts’s oscillators with BJT, Crystal oscillators, Frequency and amplitude stability of oscillators. 1.1 Introduction: Feedback Concept: Feedback: A portion of the output signal is taken from the output of the amplifier and is combined with the input signal is called feedback. Need for Feedback: • Distortion should be avoided as far as possible. • Gain must be independent of external factors. Concept of Feedback: Block diagram of feedback amplifier consist of a basic amplifier, a mixer (or) comparator, a sampler, and a feedback network. Figure 1.1 Block diagram of an amplifier with feedback A – Gain of amplifier without feedback. A = X0 / Xi Af – Gain of amplifier with feedback.Af = X0 / Xs β – Feedback ratio. β = Xf / X0 X is either voltage or current. 1.2 Types of Feedback: 1. Positive feedback 2. Negative feedback 1.2.1 Positive Feedback: If the feedback signal is in phase with the input signal, then the net effect of feedback will increase the input signal given to the amplifier. This type of feedback is said to be positive or regenerative feedback. Xi=Xs+Xf Af = = = Af= Here Loop Gain: The product of open loop gain and the feedback factor is called loop gain. -

Unit I Microwave Transmission Lines

UNIT I MICROWAVE TRANSMISSION LINES INTRODUCTION Microwaves are electromagnetic waves with wavelengths ranging from 1 mm to 1 m, or frequencies between 300 MHz and 300 GHz. Apparatus and techniques may be described qualitatively as "microwave" when the wavelengths of signals are roughly the same as the dimensions of the equipment, so that lumped-element circuit theory is inaccurate. As a consequence, practical microwave technique tends to move away from the discrete resistors, capacitors, and inductors used with lower frequency radio waves. Instead, distributed circuit elements and transmission-line theory are more useful methods for design, analysis. Open-wire and coaxial transmission lines give way to waveguides, and lumped-element tuned circuits are replaced by cavity resonators or resonant lines. Effects of reflection, polarization, scattering, diffraction, and atmospheric absorption usually associated with visible light are of practical significance in the study of microwave propagation. The same equations of electromagnetic theory apply at all frequencies. While the name may suggest a micrometer wavelength, it is better understood as indicating wavelengths very much smaller than those used in radio broadcasting. The boundaries between far infrared light, terahertz radiation, microwaves, and ultra-high-frequency radio waves are fairly arbitrary and are used variously between different fields of study. The term microwave generally refers to "alternating current signals with frequencies between 300 MHz (3×108 Hz) and 300 GHz (3×1011 Hz)."[1] Both IEC standard 60050 and IEEE standard 100 define "microwave" frequencies starting at 1 GHz (30 cm wavelength). Electromagnetic waves longer (lower frequency) than microwaves are called "radio waves". Electromagnetic radiation with shorter wavelengths may be called "millimeter waves", terahertz radiation or even T-rays.