The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory P&E 2021X Copy with ADS.Indd

Annual Directory of Producers & Engineers Looking for the right producer or engineer? Here is Music Connection’s 2020 exclusive, national list of professionals to help connect you to record producers, sound engineers, mixers and vocal production specialists. All information supplied by the listees. AGENCIES Notable Projects: Alejandro Sanz, Greg Fidelman Notable Projects: HBO seriesTrue Amaury Guitierrez (producer, engineer, mixer) Dectective, Plays Well With Others, A440 STUDIOS Notable Projects: Metallica, Johnny (duets with John Paul White, Shovels Minneapolis, MN JOE D’AMBROSIO Cash, Kid Rock, Reamonn, Gossip, and Rope, Dylan LeBlanc) 855-851-2440 MANAGEMENT, INC. Slayer, Marilyn Manson Contact: Steve Kahn Studio Manager 875 Mamaroneck Ave., Ste. 403 Tucker Martine Email: [email protected] Mamaroneck, NY 10543 Web: a440studios.com Ryan Freeland (producer, engineer, mixer) facebook.com/A440Studios 914-777-7677 (mixer, engineer) Notable Projects: Neko Case, First Aid Studio: Full Audio Recording with Email: [email protected] Notable Projects: Bonnie Raitt, Ray Kit, She & Him, The Decemberists, ProTools, API Neve. Full Equipment list Web: jdmanagement.com LaMontagne, Hugh Laurie, Aimee Modest Mouse, Sufjan Stevens, on website. Mann, Joe Henry, Grant-Lee Phillips, Edward Sharpe & The Magnetic Zeros, Promotional Videos (EPK) and concept Isaiah Aboln Ingrid Michaelson, Loudon Wainwright Mavis Staples for bands with up to 8 cameras and a Jay Dufour III, Rodney Crowell, Alana Davis, switcher. Live Webcasts for YouTube, Darryl Estrine Morrissey, Jonathan Brooke Thom Monahan Facebook, Vimeo, etc. Frank Filipetti (producer, engineer, mixer) Larry Gold Noah Georgeson Notable Projects: Vetiver, Devendra AAM Nic Hard (composer, producer, mixer) Banhart, Mary Epworth, EDJ Advanced Alternative Media Phiil Joly Notable Projects: the Strokes, the 270 Lafayette St., Ste. -

Remembering Hadewijch

Remembering Hadewijch The Mediated Memory of a Middle Dutch Mystic in the Works of the Flemish Francophone Author Suzanne Lilar Tijl Nuyts, University of Antwerp Abstract: Commonly known as one of the last Flemish authors who resorted to French as a literary language, Suzanne Lilar (1901-1992) constitutes a curious case in Belgian literary history. Raised in a petit bourgeois Ghent-based family, she compiled a complex oeuvre consisting of plays, novels and essays. In an attempt to anchor her oeuvre in the literary tradition, Lilar turned to the writings of the Middle Dutch mystic Hadewijch (ca. 1240), remodelling the latter’s memory to her own ends. This article argues that Lilar’s remembrance of Hadewijch took shape against the broader canvas of transfer activities undertaken by other prominent cultural mediators of Hadewijch’s oeuvre. Drawing on insights from memory studies and cultural transfer studies, an analysis of Lilar’s mobilisation of Hadewijch in two of Lilar’s most important works, Le Couple (1963) and Une enfance gantoise (1976), will show that Lilar’s rewriting of the mystic into her own oeuvre is marked by an intricate layering of mnemonic spheres: the author’s personal memory-scape, the cultural memory of Flanders and of Belgium, and a universal ‘mystical’ memory which she considered to be lodged within every human soul. In teasing out the relations between these spheres, this article will demonstrate that Lilar aimed to further the memory of Hadewijch as an icon of (Neo)platonic nostalgia and as a marker of Flemish and -

Appendix I Chemistry Syllabi 2011-2012 Academic Year

Appendix I Chemistry Syllabi 2011‐2012 Academic Year Introduction to Chemistry Fall 2011 CHEM1003.1 CRN60090 Dr. Draganjac LSW549 Office LSW542 Lab [email protected] LSW534 Lab 972-3272 Course: 9:00 - 9:50 MWF LSE507 Office hours: 10:00 – 10:50 am MTW; 9:00-10:50 R (Others by appointment) Text: no text Tests: 5 exams (500 points total for the exams). One exam at the end of each of the sections listed below: General Education Science Learning Outcomes/Objectives Objective Description Using Science to Students will be able to understand concepts of science as Accomplish Common they apply to contemporary issues. Goals Section 1. Metric System, Temperature Systems/Conversions, Significant Figures, Unit Conversions, Density, Review of Math, Operation of Electronic Calculators* 2. Chemical Symbols, Atomic Theory, Law of Definite/ Multiple Proportions, Periodic Table**, Writing Formulas, Naming Compounds 3. Stoichiometry, Mole Concept, Percent Composition, Empirical and Molecular Formulas, Writing and Balancing Equations 4. Theoretical yield, Limiting reactants, Solutions, Molarity, Dilutions 5. Gas Laws Course related worksheets Final exam: Friday, December 9, 2011, 8 am. The final will not be comprehensive. Quizzes: 100 points - there will be 15 quizzes (10 points each), the 5 lowest quiz grades will be dropped to give a total of 100 points Total points : 600 Grading - Straight percentage: 90+ A, 80 - 89.9999 B, 70 - 79.9999 C, 60 - 69.9999 D, Below 60 F. Make up exams will be given at the end of the semester. Failure to take the exam at the scheduled time will result in a grade of zero for that exam. -

Prisotnost Zdravstvenih Tem V Stripu Alan Ford Diplomsko Delo

UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŢBENE VEDE Pavle Terzič Prisotnost zdravstvenih tem v stripu Alan Ford Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2012 UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŢBENE VEDE Pavle Terzič Mentorica: doc. dr. Tanja Kamin Prisotnost zdravstvenih tem v stripu Alan Ford Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2012 »Torej, mladi moţ, najprej se moraš naučiti osnovni zakon oglasa: Vse mora biti jasno, tako rekoč enostavno, pravzaprav niti malo zapleteno, ampak natančno in izrazito, vsekakor izzivalno, vsiljivo in rahlo skrivnostno, da vsakdo razume vse na prvi pogled. Jasno?« (Secchi in Raviola 1971i, 56) Zahvala doc. dr. Tanji Kamin za mentorstvo in prijetno izkušnjo v času študija, Violeti, vsem otrokom, ki so se rodili v nekih lepših časih. Prisotnost zdravstvenih tem v stripu Alan Ford Diplomsko delo raziskuje narativne vidike mediatizacije zdravstvenih tveganj v stripu kot mediju. Izhaja iz razmišljanja, da imajo mediji pomembno vlogo pri oblikovanju in posredovanju pomenov o zdravju. Na zastavljeno ključno raziskovalno vprašanje, ki je, katera tveganja za zdravje se pojavljajo v stripu Alan Ford, kako pogosto in v kakšnem kontekstu, poskusim odgovoriti s kvalitativnim pristopom k analizi vsebine vseh prvih izdaj stripa Alan Ford, ki so izšli med leti 1970 in 1980. V kontekstu popularne kulture ţelim ugotoviti, ali strip medijske reprezentacije zdravstvenih tveganj utrjuje, dopolnjuje ali problematizira. Raziskava je potrdila, da mediatizirana zdravstvena tveganja v stripu kot mediju in ţanru popularne kulture obstajajo in sledijo nekaterim drugim znanim zvrstem popularnih tekstov, kot so filmi, oglaševalske vsebine, televizijski programi in časopisi. Izpostavljena tveganja za zdravje so: zloraba alkohola, prekomerna telesna teţa in debelost, kajenje, vpliv okoljskih bremen, uporaba prepovedanih drog, tveganja na delovnem mestu, podhranjenost otrok, zvišan krvni sladkor, telesna neaktivnost, povišan krvni tlak in nezadosten vnos sadja in zelenjave. -

1974-75. INSTITUTION Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C.; Linguistic Society of America, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 107 131 FL 006 895 TITLE Guide to Programs in Linguistics: 1974-75. INSTITUTION Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C.; Linguistic Society of America, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 75 NOTE . 235p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$12.05 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *College Language Programs; *College Program;Course Descriptions; Degrees (Titles); Financial Support; Higher Education; Language Instruction; *Linguistics; *Program Descriptions; *Program Guides; Summer Institutes; Uncommonly Taught Languages; Universities ABSTRACT This is a current guide to linguisticsprograms in the United States and Canada. One hundred and sixty-seven institutions are listed which offer fiveor more courses broadly defined as "linguistics" and which also offera degree in linguistics or a degree in another area with a major or minor in linguistics. The institutions' are listed in alphabetical order and under eachentry is given all or part of the following information:name of department, program, etc., and-chairman; a brief description of the program and facilities; course offerings or courseareas; staff; financial support available; academic calendar for 1974-75,;name and address the office from which to obtain brochures, catalogues,etc. Information about annual summer institutes is given in AppendixA. Appendix B is a tabular index of universities and their degree offerings, arranged by state, and Appendix C lists schools which teach at least three courses in linguistics. AppendixD is an index of uncommonly-taught languages indicating which institutionsoffer instruction in them. Appendix E is an index of staff, and AppendixF is an index of linguistis in other departments. (Author/AM) c, Guide toPrograms In Linguistics: E.4.1.1.4 ^EL. -

Literature of the Low Countries

Literature of the Low Countries A Short History of Dutch Literature in the Netherlands and Belgium Reinder P. Meijer bron Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries. A short history of Dutch literature in the Netherlands and Belgium. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague / Boston 1978 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/meij019lite01_01/colofon.htm © 2006 dbnl / erven Reinder P. Meijer ii For Edith Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries vii Preface In any definition of terms, Dutch literature must be taken to mean all literature written in Dutch, thus excluding literature in Frisian, even though Friesland is part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in the same way as literature in Welsh would be excluded from a history of English literature. Similarly, literature in Afrikaans (South African Dutch) falls outside the scope of this book, as Afrikaans from the moment of its birth out of seventeenth-century Dutch grew up independently and must be regarded as a language in its own right. Dutch literature, then, is the literature written in Dutch as spoken in the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the so-called Flemish part of the Kingdom of Belgium, that is the area north of the linguistic frontier which runs east-west through Belgium passing slightly south of Brussels. For the modern period this definition is clear anough, but for former times it needs some explanation. What do we mean, for example, when we use the term ‘Dutch’ for the medieval period? In the Middle Ages there was no standard Dutch language, and when the term ‘Dutch’ is used in a medieval context it is a kind of collective word indicating a number of different but closely related Frankish dialects. -

Issue 117.Pmd

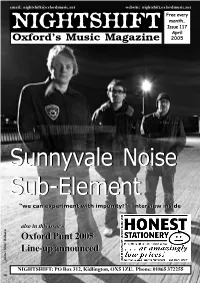

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 117 April Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SunnyvaleSunnyvale NoiseNoise Sub-ElementSub-Element “we“we cancan experimentexperiment withwith impunity!”impunity!” -- interviewinterview insideinside alsoalso inin thisthis issueissue -- OxfordOxford PuntPunt 20052005 Line-upLine-up announcedannounced photo: Miles Walkden photo: Miles NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE LINE-UP FOR THIS YEAR’S OXFORD PUNT HAS BEEN finalised. The Punt takes place on Wednesay 11th May and features 24 local bands and solo artists playing across eight venues on one night. The Punt is now established as the best showcase of local unsigned music. This year Nightshift received over 100 demos from local acts hoping to take part. The Punt received an added boost last month when Kiss Bar became the eighth venue to be added to the event, meaning we could fit an extra three bands on the bill, making this the biggest Punt ever. The full line up is as follows: Borders: 6.15pm: Laima Bite; 7pm: Kate Chadwick. Jongleurs: 7.30: The Evenings; 8.15: A Silent Film; 9pm: The Factory THE YOUNG KNIVES release a new EP on May 16th on hot new indie Far From The Madding Crowd (in conjunction with Delicious Music): label Transgressive, the label that launched The Subways earlier this 8.15: Zoe Bicat; 9.15: The Thumb Quintet; 10.15: Chantelle Pike. year. Tracks on the limited 10” EP are ‘Coastgard’, ‘Kramer Vs The City Tavern: 8.30: The Half Rabbits; 9.30: Fell City Girl; 10.30: Kramer’, ‘Weekends And Bleak days’ and ‘Trembling Of The Trails’, all Junkie Brush. -

Nestande Seeks Dismissal of Ex-Supervisor's Libel Suit

-•, Women can sway Searchers zero in on kidnapper vote NOW chief Detectives received more than 1.000 By LISA MAHONEY runn1n1 mate. Gcr1.ld1ne terraro. - ---- Of .. ...,,.. ..... phone calls about abducted HB $Ir! With thlkl na I\ SQ, Women can determine the ou1- "Femro is crca1in1 a d1fli rent 8y ITEVE MARBU: comc of the prts1dcn1i1l race. EJlje lntcrtst level from womeo in this o. ....., ........ S.meal, former ptttident of the NI· cl~lion. It wouldn't be a blllpme For tht first umc llntt li11Je Laura uonal Orpni2.11ion of Women, 1ay1. wnhout her 1n it, .. he aid. Bradbury vani hed ftom her f'amily"t Speaking before I aroup or •bout Smeal, 4S, drew on raearch she deRt't campsite 1 week 110. 17S tludent1 and NOW supponcrs at collected for her book .. Why and How au1.horit1es cxpreaed Opllmiun tl\lt UC Irvine Wednesday night, Smeal Women Will .Elect the Next Presi ~ arep1n1nssround on a man they said the much-discus~ Gellder Gap dent." for her lecture. Women, who bc:hevc abducted the Huntus1i.on -d1ffertnm in the way women and make ul? Sl perctnt of the American Beach11rl. men vote on issues - could upset population, are voting in areatcr four w11neilt$ lold authoritJt'5 President ~ei&an's re-election bid. numbe~ than men: Smeal &aid. And they art convinced they ..-w the S~~I . 1n ~er talk and durina an 12 percent fewer women than men blond·ha1ml 11rt with a bald.to,. &raY· ear her 1nterv1ew, SA.id 1he believes the s1.1pPol1 President Reapn's pohcin, haired man in his SO. -

Fonds Suzanne LILAR Inventaire Détaillé

Archives et Musée de la Littérature : www.aml-cfwb.be Fonds Suzanne LILAR Inventaire détaillé LE BURLADOR 1/ Les éditions (MLA 20028-20033): [Editions francophones] MLA 20028 - Le Burlador, Bruxelles : Ed. des Artistes, 1945, 169 p. MLA 20029 - Le Burlador, Bruxelles, Ed. des Artistes, 1945, 170 p. Exemplaire sur Japon nacré, cartoné, imprimé pour Suzanne Lilar MLA 20030 - Le Brulador, Bruxelles, Ed. des Artistes, 1945, 169 p. Exemplaire incomplet mais corrigé MLA 20031 - Le Burlador: Acte II, avant-dernière scène; précéde de, Prestige de Don Juan. In: "Offrandes", mars-avril 1947, p. 12-18 MLA 20032 - Burlador ou l'ange du démon. Supplément à France illustration n° 2, avril 1947, p. 15 à 38. Exemplaire corrigé. [Edition de traduction] MLA 20033 - The Burlador. In : Two Great Belgian Plays about Love. New York, James H. Heineman, Inc. , 1966, transl. by Marnix Gijsen, intr. by S. Lilar, p. 102-190. 2/ Les archives (ML 07551/0001-0024): [Manuscrits de Lilar] classés chronologiquement ML 07551/0001 - Le Burlador Man. aut. (crayon) et dact., n. s., s. d. [1943], 95 f., formats divers. avec une note aut. de 2 f. sur la chiromacie. Le tout dans une chemise brune à ressort. ML 07551/0002 - Le Burlador Man. aut., n. s., s. d., 51 f., 44 x 28 cm Manuscrit recopié à la demande des organisateurs d'une exposition. Les 34 premières pages sont écrites de la main de S. Lilar, les 17 pages suivantes sont copiées de la main de la mère de S. Lilar. 1 ML 07551/0003 - Prestige de Don Juan Man. -

Heritage Days 14 & 15 Sept

HERITAGE DAYS 14 & 15 SEPT. 2019 A PLACE FOR ART 2 ⁄ HERITAGE DAYS Info Featured pictograms Organisation of Heritage Days in Brussels-Capital Region: Urban.brussels (Regional Public Service Brussels Urbanism and Heritage) Clock Opening hours and Department of Cultural Heritage dates Arcadia – Mont des Arts/Kunstberg 10-13 – 1000 Brussels Telephone helpline open on 14 and 15 September from 10h00 to 17h00: Map-marker-alt Place of activity 02/432.85.13 – www.heritagedays.brussels – [email protected] or starting point #jdpomd – Bruxelles Patrimoines – Erfgoed Brussel The times given for buildings are opening and closing times. The organisers M Metro lines and stops reserve the right to close doors earlier in case of large crowds in order to finish at the planned time. Specific measures may be taken by those in charge of the sites. T Trams Smoking is prohibited during tours and the managers of certain sites may also prohibit the taking of photographs. To facilitate entry, you are asked to not B Busses bring rucksacks or large bags. “Listed” at the end of notices indicates the date on which the property described info-circle Important was listed or registered on the list of protected buildings or sites. information The coordinates indicated in bold beside addresses refer to a map of the Region. A free copy of this map can be requested by writing to the Department sign-language Guided tours in sign of Cultural Heritage. language Please note that advance bookings are essential for certain tours (mention indicated below the notice). This measure has been implemented for the sole Projects “Heritage purpose of accommodating the public under the best possible conditions and that’s us!” ensuring that there are sufficient guides available. -

Plameni Pozdravi, Šestokanalna Video Instalacija (363 Fotografije I Tekstovi Iz Fotografskih Albuma Poslatih Titu Od 1945

ANA ADAMOVIĆ Plameni pozdravi, Šestokanalna video instalacija (363 fotografije i tekstovi iz fotografskih albuma poslatih Titu od 1945. do 1980. godine iz arhiva Muzeja istorije Jugoslavije) 4 5 Ana Adamović Saša Karalić PLAMENI POZDRAVI KVADRAT 13-17 189-190 Dubravka Ugrešić i Ana Adamović Irena Lagator Pejović RAZGOVOR SLOBODA SIGURNOST NAPREDAK 27-34 193-194 Olga Manojlović Pintar Mladen Miljanović ŠEST TEZA O ODRASTANJU LAKOĆA SEĆANJA I TEŽINA ISKUSTVA U SOCIJALISTIČKOJ JUGOSLAVIJI 197 53-62 Škart Radina Vučetić ŠTA PITAŠ KAD NIKO NE PITA? PAJA PATAK S PIONIRSKOM MARAMOM 201 (Socijalističko detinjstvo na američki način) 81-91 Milica Pekić, Branislav Dimitrijević i Stevan Vuković Igor Duda TRANSKRIPT RAZGOVORA DOSTA VELIKI DA NE BUDU MALI održanog 9. aprila 2015. godine 109-111 u okviru izložbe Plameni pozdravi u Muzeju istorije Jugoslavije Nenad Veličković 205-212 ALBUMI, KROKI 125-129 Dejan Kaludjerović i Ana Adamović RAZGOVOR Škart 215-218 pesme iz zbirke ŠTA PITAŠ Renata Poljak i Ana Adamović KAD NIKO NE PITA? RAZGOVOR 141-145 221-225 Martin Pogačar Dušica Dražić i Ana Adamović KRAJ DETINJSTVA: RAZGOVOR šta se dogodilo sa utopijom socijalističkog detinjstva 227-230 i šta u tom pogledu može učiniti nostalgija? 157-164 Maja Pelević i Vuk Pelević CRVENA ZVEZDA OPKOLJENA ZLATOM Ana Hofman 237-243 RASPEVANO SOCIJALISTIČKO DETE? 175-178 Hronologija socijalističke Jugoslavije 244-247 Ildiko Erdei HOR Biografije autora 181-185 249-253 Izložba Plameni pozdravi Muzej istorije Jugoslavije, mart-april 2015. ŠKART ŠTA PITAŠ KAD NIKO NE PITA? (Krevetne pozorišne priče) Izložba Plameni pozdravi Muzej istorije Jugoslavije, mart-april 2015. 13 ANA ADAMOVIC Sredinom 2011. -

DANTE NEWS SOCIETÀ DANTE ALIGHIERI "Il Mondo in Italiano"

DANTE NEWS SOCIETÀ DANTE ALIGHIERI "il mondo in italiano" Newsletter of the Dante Alighieri Society Inc. Brisbane APRILE 2021 DANTE ALIGHIERI SOCIETY 26 Gray Street, New Farm, QLD 4005 Postal address: PO Box 1350 New Farm, QLD 4005 Calendario Phone: 07 3172 3963 Mobile : 0401 927 967 Email: [email protected] Web address: www.dante -alighieri.org.au April 4 – BUONA PASQUA PRESIDENT Claire Kennedy April 19 – Start of TERM 2 [email protected] VICE -PRESIDENTS Rosalia Miglioli April 23 – Conversazioni [email protected] Mario Bono [email protected] April 25 – Cineforum SECRETARY Colleen Hatch [email protected] TREASURER April 29 – Adelaide presents DANTE Kay Martin info@dante -alighieri.com.au EDITOR GUEST EDITORS Bernadine e Rosalia Inside ○ Annual Report ○ Dalla scuola ○ Dalla biblioteca ○ Autobiografia Master chocolatier Fabio Ceraso works on a record-breaking Easter egg dedicated to the 700th anniversary of Dante Alighieri’s death made in a chocolate factory in Na- ples, Italy, on March 20, 2021. (Photo: AAP) https://lafiamma.com.au/en/news/naples-pays-tribute-to-dante-with-giant- easter - egg - 59772/ Pagina 2 SOCIETÀ DANTE ALIGHIERI, BRISBANE aprile 2021 Dante matters President’s report to A.G.M. continues… Cari soci, The prizes for this year’s winners will be presented later this year, on May 28, in conjunction with a It is with much pleasure that I present the celebration of acclaimed author Leonardo Sciascia President’s Report for the year 2020, the 68th year by Tiziana Miceli. Another initiative, ‘Danteatro’, of the Society and my 8th year as President.